3 Archaeology and Material Culture

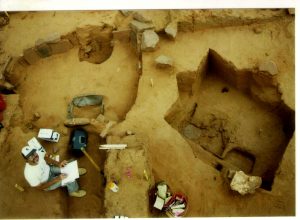

Phil Geib

Learning Objectives

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter, students will:

- know some of the basics about archaeology

- know about how material remains can inform about the past

- know about some of the theoretical approaches in archaeology

What is Archaeology?

A simple definition is that archaeology is the study and preservation of the material remains of past societies and their environment.

Some definitions don’t include preservation, but that is an important addition. Preservation is why the ranks of archaeologists in America and elsewhere have increased more than 100 fold since the 1950s. There are plenty of jobs in archaeology because of cultural resource management or CRM: studying, managing and preserving the material remains of past societies.

The material remains that archaeologists study consist of these three: artifacts, ecofacts, and features. These are what archaeologists find and document with context being a critically important variable. In many cases these material remains occur in concentrations that are referred to as archaeological sites. A definition for that concept will be presented shortly but first let us consider those three classes of material remains.

Material Remains

- What are Artifacts? Artifacts are products made by the hands of people such as flaked or ground stone tools, ceramic pots, woven cordage bags, and the list goes on and on. It’s our material culture. Whole fancy artifacts are often put on display in museums and shown in photographs in public reports but most artifacts that archaeologists usually find and not like this. Archaeologists mostly recover trash: items broken or worn out and hence and discarded by the people that made and used them.

Unfortunately there is a preservation problem with much material culture and this has a significant impact on our understanding of past societies. A famous archaeologist of yesteryear Alfred Vincent Kidder once made a “survival survey” of the vast collection of artifacts that he had recovered from the caves in NE Arizona: Of the hundreds of objects, filling five large display cases and many storage drawers, he found that just about 60 would be recovered in a normal excavation. “The whole lot would have gone into a good-sized soup plate. . . That pitiful residue would have told us nothing of how people cradled & diapered their babies, how they dressed, how they wore their hair …It would have given us no inkling of their extraordinary skill as weavers & wood-workers.” Kidder had intimate knowledge of all these and many other details of past life because of excellent preservation. But in the overwhelming majority of ancient cultures this knowledge is lost beyond recall because of the preservation problem.

- What are Ecofacts? Ecofacts are items from nature such as plant pollen and animal bones. These can be a direct result of human activity or they can be natural inclusions that help to inform about environments that people lived in. Sometimes it’s tricky distinguishing between these and making sure that ecofacts pertain to what we think that they do. For example, is an animal bone a result of human hunting or natural death? This vary question is the source of the large and often angry debate that has swirled around the Hudson-Meng Paleoindian site in far western Nebraska. Bison clearly died there, but did humans cause their death? With archaeology, as with any science, “the devil is in the details.” In the Hudson-Meng case the details of careful stratigraphic excavation and association between the bones and the flaked stone points and other artifacts.

- What are Features? Features are non-portable evidence of past human behavior, activity, and technology, such as hearths, storage pits, walls, kilns for firing pottery, and structures. Features are distinguished from artifacts since they cannot be separated from their location (their context) without changing their form. You can excavate artifacts and take them back to a laboratory for study. Features can not be brought back to the lab in the same form that they were found. If you excavate a

Archaeological Sites are places on the landscape or under water where artifacts, ecofacts and features are concentrated. An archaeological site is some location where humans lived or conducted some activity that resulted in the deposition and accumulation of materials remains. Archaeological sites can be small, such as a single camp fire with a few associated artifacts from where a hunter spent a night. Sites can also be large such as an entire city. The site of Cahokia near the modern day site of St. Louis is a good example of a very large site. It was the largest city of North America prior to modern times and one of the largest cities in the world when it was at its peak at about 1000 AD.

In the United States, most federal & state agencies have definitions of what qualifies as an archaeological site. If you find a single isolated feature, such as a hearth, then that qualifies as a site. In many cases where ever people spent enough time to make a fire archaeologists will also find some associated artifacts that they also left behind. Not always though.

If you find a single artifact, that might or might not qualify as a site; it depends on the find context and the nature of the artifact. If it’s a single jar, like the example shown below, then that qualifies as a site. This cached jar was found under a rock ledge in NE Arizona were someone placed it there roughly 1000 years ago (we know the approximate timing based on the design style of the vessel, which has a temporal span assigned by tree-ring dating). Vessels like this get placed in hidden locations for special purposes such as caching food or gear that will be important for the future. A stone lid once covered this jar, but it now rests against its side and the the jar is empty.

Spatial & Temporal Distributions

Material Remains are distributed in space & time. These are the two key dimensions that archaeologists need to control. Space is relatively straightforward and has gotten easier by modern techniques of mapping and visualization (GPS and GIS). Time is based on having some sort of absolute or relative dating technique. Establishing the temporal placement of archaeological materials is tricky. It is constantly improving as new techniques are developed and older techniques are improved. Radiocarbon dating, for example, has seen many improvements over the decades since it was initially developed in the late 1940s and 1950s.

Radiocarbon dating is an absolute dating technique. With radiocarbon you can assign a chronological age estimate to an organic artifact, a bone, or other remains containing carbon. The age assigned to a sample can then be extended to the layer within which the sample was obtained. To learn in simple terms how radiocarbon dating works please watch the informative video provided by Scientific America by clicking this link: https://youtu.be/phZeE7Att_s

- Temporally Diagnostic Artifacts

With sufficient study in combination with some form of absolute dating, stylistically distinctive artifacts can be treated as temporal markers, independent of dating the actual item itself. One example is provided by the Clovis projectile point, an example of which is shown in the image below. This highly distinctive point style was only made for a limited time by early Paleoindians of North America who hunted woolly mammoth and other game. Radiocarbon dates on organic materials in association with these points, such as bone or charcoal, have

demonstrated that this style of point was made and used some 13,000 years ago. This particular find was made by a collector on an eroded stream terrace in a southern county in Nebraska. The point was out of context, which means not in the original place of deposition. This point might well have been a missed shot that the hunter was unable retrieve while in hot pursuit of their quarry. (A find like this, despite being spectacular and one in a lifetime, generally does not qualify for designation a site since it lacks context).

Another example of a temporally diagnostic artifact is the open-twined sandal shown in the image below. In this case temporal assignment is known by directly dating actual examples of the artifacts, since they are made of yucca leaves. These sandals were in common use by Archaic Period hunter-gatherers on the Colorado Plateau of the US Southwest. Despite being more than 6000 years old, these perishable artifacts are preserved by having been discarded in rockshelters or caves that limit moisture rot. What makes the sandals distinctive is how they were made using a series of whole yucca leaves folded over at the toe and then secured by several passes of additional yucca leaves that were twined (twisted) around the folded leaves. These sandals are relatively quick to make with a pair taking only about 15 minutes when you have the materials ready at hand.

The original means of radiocarbon dating required destruction of all or most of a single sandal in order to obtain a date (the organics must be combusted to gas and the pure carbon dioxide retained for dating purposes). A new radiocarbon dating technique developed in the early 1980s known as accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS), allows for minute samples to be dated since it involves direct counting carbon-14 atoms relative to the carbon-12 atoms. In the past 30 years more than two dozen open-twined sandals have been directly radiocarbon dated by the AMS technique. These dates demonstrate that the sandals were in fashion between 6600 and 8300 radiocarbon years ago. When you find a sandal like this, you know that you have an early site.

One of the authors of this book (PR Geib) has also worn replicated examples of the open-twined sandals to test out how they work; to learn what their benefits are and how they compare with another type of sandal that was next used by hunter-gatherers on the Colorado Plateau. This is one example of an important method that archaeologists use to learn about the past. One part is best termed experiential archaeology, where you try making or using some past artifact to see how feasible it is to make and use; whether something can actually work or the time and effort required. With experience in making and using a past technology archaeologists can conduct more formal experiments to test alternative hypotheses about how artifacts were made or used. Experiments can also be used to generate analogues for comparison against materials from the archaeological record.

Archaeological Research Questions

Archaeologists study material remains to answer questions about the past. We ask a slew of questions. Some are simple descriptive ones. Some a complex explanatory ones. The simple ones tend to be those of who, what, where, and when. The complex and often intractable questions concern process or how something in the past occurred and explanations of causality, or why something in the past occurred as it did.

A sample of archaeological questions includes the following list:

- Who were the people of the past?

- Where did they come from?

- How did they interact with neighbors?

- How did they survive?

- How did their lifeway change?

- Why did their lifeway change?

The last question is an explanatory one and it is any question that concerns why is inherently quite difficult. Yet even the apparently simple question of who a people in the past where presents my challenges. Identity is something that is self proclaimed and socially constructed in the context of other people. How can this be known archaeologically? Archaeologists refer to past peoples by some common and distinct artifact or other material trait, such as Clovis projectile points. But the people that used such points and that get lumped together as Clovis peoples likely thought of themselves as something entirely different and considered other people also using Clovis points are totally different from them.

Materialized Behavior and History

Archaeologists try to reconstruct past human behavior & history using the material remains that peoples left behind. We document, describe, measure, classify, analyze & interpret material culture in order to do such reconstruction. The interests of archaeologists extend from the fate of uniquely preserved individuals such Ötzi the Ice Man to the fate of various sized social groups from family units to states. Our interests extend from from local short-term history to global long-term history.

Archaeologists are something akin to a detective, trying to solve a crime with no witnesses, such as when a dead body surfaces. This is essentially what happened with Ötzi the Iceman (shown below and with the video in this link providing a quick synopsis: https://www.smithsonianchannel.com/video/series/mummies-alive/36308 ), although his murder happened a very long time ago: ~3200 BC (there are no statute of limitations for murder but clearly the person[s] responsible are beyond criminal punishment). Just like detectives of a modern murder, archaeologists have tried to puzzle

out how Ötzi died and who might have killed him (if indeed it was a murder). Analysis has demonstrated that there is an arrowhead lodged in his left shoulder that likely caused his death and that blood from at least four other individuals was on his tools including his knife and an arrow head (violence between people is not in doubt).

Motives are lost in the fog of time but are probably not much different than the motives at play today: sexual jealousy or revenge come to mind. Theft seems highly unlikely since he retained all personal items including his highly valuable copper axe, an object that at the time might be analogous to carrying around a gold bar today.

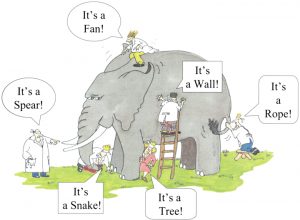

Archaeologists sometimes act like the blind men in the South Asian parable. The elephant in this case is the archaeological record or prehistory. Each archaeologist can touch a part of the same record yet have entirely different interpretations of what it is. What it means. This can be seen in the Ötzi case just discussed. Some of the arguments about different interpretations of how he died or how he came to be where he was found stem in part by over emphasis on just a portion of the evidence. It is vitally important to try putting all the various pieces together to understand the whole picture.

How is knowledge of the past possible?

The past is gone & can’t be observed so how is knowledge of it possible? This is a fundamental question that archaeologists are always faced with. There are complex issues of evidence, observation, inference, and justification. Archaeologists deploy a host of methods in response to the question of how knowledge of the past is possible. Key among them is analogy and the assumption of uniformitarianism, or the doctrine of uniformity.

An analogy is an inferential argument based on similarity of traits between a known, the analogue, and an unknown. The goal is to assign additional traits to an unknown based on the similarity of traits with a known. The more traits that are shared between a known and unknown, the more that are likely to be shared. The known for an archaeologist is observed behavior and its products such as artifacts and features, such as how a stone tool of a given shape was used and the use-wear that resulted. The unknown for an archaeologist are all the material remains recovered or observed at an archaeological site, these are all products of behavior that cannot be observed. Take, for example, a prehistoric tool that resembles both in the shape and use-wear the known analogue. A credible inference could be made that the prehistoric tool was used like the modern example: the unseen behavior of the past is known with some degree of certainty.

Uniformitarianism is the belief that the same natural laws and processes that operate in the present-day have always operated in the in the past (and will so into the future) and apply everywhere in the universe. This allows predictions to be made about what will occur and understandings of what has occurred. A simple way to look at this with an archaeological example is by considering a flake (chip) of obsidian found within some ancient archaeological deposit such as the

modern example shown here. How can we recognize this as a product of human manufacture and how do we know what actions a person in the past took to detach this flake? Brittle glassy rock such as obsidian breaks in a certain predictable way called conchoidal fracture. This occurs today no different than it did 30 or 300 or 300,000 or 3,000,000 years ago. The process will also be the same 3 million years from now. If we were to find an obsidian flake like the one shown in some layer dated to 3 million years ago we would have a pretty good understanding about how this flakes was detached because of observing the behaviors today that result is such flakes. This same principal can be extended to most aspects of the material world but it does not allow all aspects of behavior in the past to be reconstructed. For example, it says nothing about how the people that detached flakes like this organized themselves socially. Solving that requires another commonly used method: ethnographic analogy

Ethnographic Analogy uses the customs and behaviors documented in ethnographic or other historical sources as a means for making inferences about what life was like for a past group of people who are known only on the basis of archaeological evidence. This approach can work best when the archaeological culture is thought to share direct ancestral ties to an known society documented by ethnographers or other written sources. An example of this is the Puebloan societies of the US Southwest, which received extensive documentation by anthropologists starting in the late 1800s. There are also Spanish sources that go back to the 1500s. The Puebloans are descendants of an archaeological culture originally called the Anasazi, a term that is no longer used in deference to Puebloan requests. Understanding the archaeological remains of ancestral Puebloans has greatly benefited by knowledge of the ethnographic record.

As one simple example of the structure of an ethnographic analogy please consider the argument that William Longacre developed for an ancestral Puebloan site in NE Arizona. He used modern day Hopi as his analogue. This western Puebloan society is one where women make the pottery and the designs on vessels are learned by transmission from mothers to daughters. Hopi have a kinship pattern reckoned through the female line (kinship is matrilineal) and their residential pattern is matrilocal (women stay in/near their natal home and their husbands move to reside with the wife and mother-in-law. On the archaeological side of the equation there was an excavated Pueblo-like settlement and at it there was spatial clustering of ceramic design styles. So, under the assumption of women being the pottery producers in prehistory just as in historic times an answer to the questions of why ceramic design styles should be spatially clustered is because the kinship of that ancient society was matrilineal and the residence pattern was matrilocal. Kinship and marital residence pattern are not things that archaeologists can excavate. But by building an analogical model like Longacre did, it is possible to make inferences about such unseen aspects of the past, inferences that have some degree of plausibility. Longacre’s assumptions include the following: 1) women made the pottery, 2) daughters learned designs from members of maternal line principally or only, 3) pottery recovery context is meaningful—the patterning in designs observed is not just random chance.

Ethnoarchaeology is another archaeological method for justifying knowledge claims about the past. Ethnoarchaeology involves studying traditional but contemporary cultures and technologies to provide analogues for reconstructing prehistoric cultures & technologies. This developed because much of the traditional ethnographic record does not provide details that concern materials that might be found in the archaeological record. Consequently there is a linkage problem between what is written about in ethnographers and the material remains that those societies generated. William Longacre advocated for this approach and spent considerable time studying traditional communities in the Philippines to learns about pottery production, use, exchange, and discard (the Kalinga Ethnoarchaeological Project).

Lewis Binford was another strong proponent of ethnoarchaeology and referred to it as mid-range research, a method for linking the static archaeological record to the behavioral dynamics that produced it. Binford saw it as a means to understand the processes that formed the archaeological record. His goal was to find the causes of the nature of archaeological expressions. Those causes may be cultural, natural or some combination of the two. Binford conducted a study of the Nunamiut Inuit in Alaska studying butchering practices and sites used as hunting stands. From these he drew various conclusions or statements about how the archaeological record gets created by hunter-gatherer societies.

Evidence Lost or transformed

Archaeological evidence is always being lost or transformed—hence the focus on preservation. As we mentioned before, much of past people’s material culture is organic, thus rarely preserved. The more recent remains are usually more visible than earlier remains—older materials can be deeply buried and only found by happenstance. The material evidence of some societies is very diffuse and scattered (foragers) thus difficult to study. The material evidence of other societies is so massive that it is difficult to study—too much evidence, too much complexity.

Goals of Archaeology

Archaeology has four main goals:

- Develop Chronology (Culture History)

- Reconstruct Past Lifeways (Culture Reconstruction)

- Explain Culture Change (Culture Process)

- Derive Meaning (Culture Interpretation).

Each of these aspects represents a different historical period in North American archaeology and a different theoretical approach. They all are still at play and which goal an archaeologist focuses in part depends on interest and training.

Establishing chronology is a central aspect of archaeology no matter one’s interest. This was originally a difficult challenge in the absence of writing or without any of the techniques that we have now for directly dating objects or the layers that objects are found in. As a result, much of the early history of archaeology was spent in trying to work out the details of who and when. The initial approach to establishing some rough ordering of materials involved a consideration of artifact material and form and by factoring in find context. Stratigraphy played a key role in this by charting the changes in artifact form in vertical space. Seriation was another key method, which involved looking at changes in artifact form in horizontal space while also at times factoring in the findings from stratigraphy. Both methods are still useful with stratigraphy being critical, but both only provide relative age. Various methods now provide direct or indirect dating—true chronological determination.

Stratigraphy concerns the analysis of the order and position of layers of archaeological remains. Recovering archaeological materials from deeply stratified sites was critical to developing relative chronologies around the world by employing the geologic axiom of superposition that Nicholas Steno devised in the 16th Century for geology:

“In any undisturbed rock and soil column, old remains are lower and more recent on top.”

This observation seems sort of basic and self obvious now, but it was an important revelation back it its day and it has placed his name in the history books.

Archaeological strata consist of undisturbed layers containing material remains. These are of great value to archaeologists and any site with finely stratified and well-differentiated layers is vastly important because they provide a finely resolved archaeological record.

- North Creek shelter in SE Utah provides a great example because it has a classic layer cake stratification. Some 3 m of cultural and natural deposition occur within this wet rockshelter. The lower layers are especially significant because brief intervals of occupation are separated

North Creek Shelter in southern Utah showing finely stratified layers laid down during the early Holocene when human foragers occupied the site (photo credit: Joel Janetski). from each other by sterile layers of washed in sediment. Getting the best research potential from a site like this means that you must excavate by natural strata. This means pealing away one layer after another and making sure that you are not mixing deposits of different intervals. That sort of excavation technique is an art form. Excavating a site like this by arbitrary excavation levels, even exceedingly fine ones of 5 cm, would have messed up the archaeological record. Because of the fine excavation technique used by Joel Janetski of BYU, this site documents some important changes in adaptation for early foragers on the Colorado Plateau. One of those includes a dramatic shift in projectile point styles from the large stemmed points earlier than 9000 bp to smaller eared points after 9000 bp. There was also a corresponding change in subsistence practices at this interval with increased emphasis on small seeds and plant resources after 9000 bp.

Key Assumptions Concerning “Who”

Part of the traditional concern in archaeology, one that is still present, concerned the question of who the people were in the past whose remains get recovered and documented. To make an account of history before writing we not only need to know when something occurred but who was doing that something. Several guiding assumptions of the culture history paradigm that include the following ones:

- Artifacts = culture; i.e., “archaeological culture”.

- Similar assemblages of artifacts within a region = same time and same people.

- Different assemblages = different time or different people.

- Cultural Change is initiated by:

- Diffusion of ideas,

- Migration of people or

- Independent invention (originally thought uncommon)

If an archaeologist could document abrupt dramatic change in the archaeological record then that was proof of either migration or invasion that resulted in population replacement. Culture historians described this as “site-unit” intrusion, and it truly can be recognized in the archaeological record because it has occurred. But change also occurs for reasons internal to a society and not because of migration or invasion.

One other assumption of the culture history approach was that within regions, cultures became more complex through time. It is true that there is a trend like this in many regions, but there are also exceptions. The archaeological record of Tasmania is one chief example, where the archaeological record shows a loss and simplification of material culture across time. Much has been written about this Tasmanian paradox. And the archaeological and historic record is full examples of civilization collapse, where societies “fail” for one reason or another and revert to less complex societal structure in terms of social, political and economic organization.

The archaeological goal of culture reconstruction involves an attempt to figure out the diverse lifeways of past societies. This stemmed from the realization that material remains are useful for more than charting culture history. One aspect of this involves determining past functions or artifacts and features and sites. What was this tool used for in the past? What was this structure used for–general living or some special purpose? What about this site, could it have been like one of the hunting stands of the Nunamiut that Binford studied?

One of the central aspects of this approach that different from that of culture history is that variability in material remains across both space and time may reflect changing functions, activities, or organization, not a change in people or ideas.

An interest in knowing something about the behaviors of past societies called from different methods from those used by culture historians or ones that were more refined. As a result experiential and experimental archaeology became important, as did ethnographic analogy and ethnoarchaeology. Also central to this approach was paleoenvironment reconstruction, determining what the natural environment was like at different points in the past. Environmental change is clearly a major driver in evolutionary change since it is the environmental context that determines respond