1 What is Anthropology?

LuAnn Wandsnider and Taylor Livingston

Learning Objectives

After completing this chapter, students will:

- Know what Anthropology is and how it relates to other social sciences.

- Know the subdisciplines of Anthropology.

- Be familiar with a brief history of the discipline.

Most of you reading this text have never taken an Anthropology course or may never have heard the word outside of popular media. Unlike other disciplines in the social sciences and humanities, Anthropology is not a field taught in high school elective or required classes. More often, as perhaps in your case, you took a course like this on the advise of a friend or advisor, or stumbled upon anthropology to fulfill general education requirements. But, you don’t have to be an anthropologist to appreciate the power and utility of an anthropological perspective. Indeed, employers seek out the very skills that are basic to anthropology.

So, what is Anthropology?

Anthropology emphasizes culture and also evolution

Anthropology relies on the concept of culture, which encompasses the social behavior and norms learned by individuals as members of social groups (see Chapter 2). Anthropology also recognizes the importance of history and change in two ways. We see the human genome changing over time along with changes in the frequencies of particular biological traits within modern human populations–all subsumed under the notion of biological evolution. Also over time, we see important changes in human behaviors and practices, that is, the cultural repertoire, documented through one of anthropology’s subdisciplines, archaeology.

Anthropology studies the Analytic Other

In common parlance, we often use the term "othering“ as a means to recognize another individual or culture as, in their fundamental essences, different from “us” and, because of those differences, possibly inferior and even dangerous.

Anthropology studies another kind of “other.” We study the Analytic Other, that is, people or cultures who are, owing to history, foreign to us, or whom we make foreign so as to study them with a qualified objectivity. (“True objectivity” is unattainable, but, we can admit what we do and don’t know.) For example, I (Livingston) was part of a study to understand how nurses and doctors communicated so as to develop interventions that would enhance that communication in order to benefit patient care. Nurses and doctors and communication are all very familiar to us but, in order to study all of these together, our team set up a study design to make them “foreign” and new. We created an Analytic Other from the familiar.

The Analytic Other also includes the WEIRD and nonWEIRD. Joseph Henrich and colleagues use the acronym WEIRD to refer to those raised in Western, Educated, Industrial, Rich, Democracies. WEIRD people are highly individualistic, self-obsessed, nonconformist, and analytical. They are the minority of the population of the world. The nonWEIRD, raised in other contexts, think of themselves as members of communities. This distinction is important because most of the knowledge we have about psychology, economy, marriage and family systems, and value systems comes to us through the lens of the WEIRD. For example, researchers pay college students at American universities to participate in studies exploring the human brain and then routinely generalize from such studies to characterize all of humanity. Yet, American college students, drawn from Western, educated, industrial, rich democracies, represent a WEIRD sample of humanity.

Anthropology is considered a social science, along with Psychology, Sociology, Political Science, Economics, Geography, and History. Psychology is the science of mind and behavior. Sociology focuses on the study of the development, structure, and functioning of human society and has tended to focus on Western societies. Political Science is the study of systems of governance. Economics focuses on the study of the production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services. Geography is that science devoted to the study of the environment and people in space. And, History features the study of the past using documents.

An anthropologist may study any of the above but, as they relate to a specific Analytic Other. For example, Henrich’s work unpacks how culture intersects with psychology.

Anthropology embraces an holistic perspective

“Holism” is familiar to us from holistic medicine. In holistic medicine, we treat the whole person, considering cultural, social, and psychological factors, not just the symptoms of a disease. Similarly, the holistic perspective in Anthropology recognizes that the whole is greater than the sum of the biological, historical, cultural, social, historical, or material aspects of being human. All of these are interconnected and one cannot be understood without also considering the other. (See Forensic Anthropology case study.)

So, in the words of Michael Wesch (The Art of Being Human), anthropologists simultaneously see small, see big, and see the connections. (He also says that we see ourselves seeing, but, we will get to that shortly). For this reason, anthropologists may often assume leadership roles, as they appreciate the knowledge of the specialist and know how to integrate it into the larger generalist picture.

Anthropology is an extreme human science

Because it is holistic, where the details of the human condition are just as important as the larger whole, and because we attend to the Analytic Other often outside our comfort zone, anthropology is also an extreme science. In addition to methods unique to it, it routinely makes use of the methods and approaches from other social sciences mentioned above as well as the natural and physical sciences (see Chapter 3).

Anthropology also relies on archaeological methods, similar those utilized in paleontology, to learn about the culture, social organization, economies and systems of governance of peoples, who, for a variety of reasons, are unable to leave behind documents. That is, we study things, their disposition and distribution. In fact, the material account of events sometimes provides a more faithful, albeit fainter, accounting of those events than historic accounts, which are written by the victor or from the viewpoint of the dominant. For example, archaeologist Douglas Scott and colleagues studied the archaeological landscape at the site of Battle of Little Big Horn. They discovered that the distribution of bullet casings and other artifacts aligned closely with Cheyenne, Lakota and Arapaho accounts of the battle. And, it differed widely from the heraldic accounts about the how Lieutenant Colonel George A. Custer and the 7th Cavalry engaged with Native combatants (“Custer’s Last Stand“) that circulated in the American press at the time.

And, paleoanthropology, another subdiscipline of Anthropology, considers how humans came to be human, that is, hominin origins, again employing methods common to field geology and paleontology as well as comparative biology and ecology. Finally, Anthropology is the only social science that takes as its purview how humans use and are used by material culture, that is, stuff . Thus, Anthropology comfortably tacks between concepts and tools used in a variety of natural (e.g., geology, zoology) and physical (e.g., chemistry) sciences as well as social sciences and humanities (English, gender studies, history)–all so as to better understand humans.

And, Anthropology is an extreme humanity, too!

Anthropology is “the most scientific of humanities, the most humanistic of sciences” (Wolf 1974[1964]: 88; also attributed to Alfred Kroeber). Anthropology also grapples with moral and ethical elements of what it means to be human. What is the obligation of the human to the group? How does gender and class modulate the relationship between individual and group? When is murder justified? Is death forever? And, what does forever even mean, if one conceives of the present as indistinguishable from the past or the future? Anthropologists draw from cross-cultural archives of human behavior and cultures to examine these and other questions. The University of Nebraska Libraries maintain access to the Human Relations Area Files, a small window into variation in these human practices and ideologies.

Anthropology is both empirical and theoretical

Subdisciplines in Anthropology

While other Social Sciences recognize specialties, Anthropology recognizes four subdisciplines or subfields, portions of the larger anthropological enterprise with distinct content, methods, and jargon: archaeology, biological anthropology, cultural anthropology, and linguistics, with specializations within each of these. These subfields began to be distinguished in the 1920s and 30s, when professional organizations devoted to each these appeared. Subsequent chapters will explore the questions and approaches explored within particular anthropological subfields; here is an overview.

Archaeology deals with the study of materials to learn about people, behaviors, cultures, and institutions, often from the past. As there are many parts to the archaeological enterprise, there are many specialties as well. Some focus on particular time periods, from very early humans to the Atomic Age. Some focus on particular classes of material culture, such as artifacts made of stone, ceramic, or glass as well as animal and human bones. Some become experts in methods, for example, drone-based documentation of excavated sites or the use of a particular tool for artifact characterization (e.g., XRF) or data organization (e.g., geographic information systems). Others develop expertise in interpretation, for example, preparing museum exhibits.

Biological anthropology focuses on the human body, its genetic history, how it varies owing to history or environment, how it is affected by cultural practice. As with archaeology, there are many ways to be a biological anthropologist. Some track into careers in epidemiology or population genetics, others focus on bioarchaeology and forensic archaeology, and still others focus on primates or hominin ancestors.

Cultural or sociocultural anthropology considers people in our world today, why they behave as they do or hold the beliefs that they hold. Just as humans are diverse, so are the pursuits of cultural anthropologists. Some focus on education,

Finally, linguistic anthropology or linguistics focuses on how people communicate and how that communication is related to biological and cultural prescribed features. Historical linguists consider how language evolves; sociolinguistics consider how language is used by different communities.

Applied anthropologists address real world problems using anthropological methods and ideas. While the American Anthropological Association (AAA) discusses applied anthropology as something recent, as discussed above, anthropology has always had an applied aspect. Where concerns of the 1700s focused on the origins of Native Americans, recent foci are much more specific. For example, in the area of cultural anthropology, Dr. Taylor Livingston, researches ways to address health disparities related to maternal and child health through social support and cultural understanding. Applying archaeological approaches to heritage, Dr. Heather Richards-Rissetto is using 3D technologies to assist efforts to document endangered monuments and interpret the history of the World Heritage site of Copan in Honduras. Dr. Belcher, straddling multiple subdisciplines, leads teams of archaeologists and bioanthropologists to recover and repatriate the remains of missing service members under the auspices of the Department of Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA; based at Offutt Air Force Base). In the realm of anthropological approaches to language, the late Dr. Mark Awakuni-Swetland (1956-2015) collaborated with a team of University of Nebraska-Lincoln students, educators, and Omaha elders to develop The Omaha Language and the Omaha Way: An Introduction to Omaha Language and Culture (2018; University of Nebraska Press), an novel pedagogical method to teach the Omaha language through Omaha culture. Such resources are essential for endangered languages to persist.

A Brief History of Anthropology

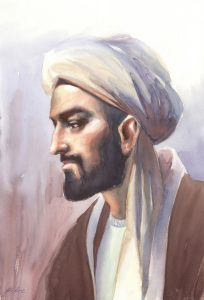

Anthropology in its modern form is closely tied to the colonialism that followed from the expansion of empires in 1500s. But, one of the projects of modern anthropology, pursuing the “science of culture,” can be seen in the work of Ibn Khaldūn (1332-1406) an administrator and historian based in what is now north Africa and writing in the late 1300s. He is known for his Al Muqaddimah, a theory of human society based on his close read of individuals, tribes, and cities in north Africa. He noticed a pattern wherein tribal leaders operating on the periphery of states could build an esprit d’corps through tribalism magnified by religion (Arabic: ‘abasiyyah), creating both effective leadership and collective action. Such groups successfully challenged the leadership in cities; replacing those leaders, however, eventually resulted in the dissipation of ‘abasiyyah, as newly installed leaders succumbed to maintaining their now comfortable life-styles in the cities. “The ruling tribes and elites are replaced on a cyclical basis but the system remains stable. This is the nature of the Khaldunian cycle” (Alatas 2014:42). Ibn Khaldūn’s observations influenced scholars in the Renaissance and Enlightenment and he is often regarded as the father of philosophy, economics, history, and sociology and is widely cited by geographers and anthropologists.

In the United States, anthropology was shaped by and continues to be shaped by pressing questions of the day, often with significant policy implications (Table 1.) In the Early Republic, the the question was how to think about the three different races–White European colonizers, enslaved and free Black Africans, and indigenous Native Americans–then co-residing. Were the obvious morphological differences in skin color superficial or did they reflect innate and immutable differences in mental or physical abilities? While Native North America was predominantly occupied by farmers just prior to the European invasion, exposure to European diseases took a severe toll and, by the time of colonization, some native agricultural economies had collapsed (Cronin ). Scholars of the day, thus, debated how to reconcile 1) morphological similarities between Native and Whites; 2) the great diversity and complexity of Native languages and massive abandoned mound complexes (like that at Aztalan, which had not yet been discovered), suggesting an ancient tenure and superior organization; and, 3) the less advanced state of Natives as suggested by a hunting and gathering rather than agricultural subsistence. The discourse on this is uneven and contradictory even by individual scholar and very much influenced by the wants and needs of the dominant society, as it expanded into territory occupied by Native groups.

Much of the observation on native peoples at this time was ad hoc and crowd-sourced. Explorers and missionaries were asked by people such as Thomas Jefferson (Virginian plantation owner, enslaver, principle author of the Declaration of Independence, and third president of the United State; 1743-1826) to provide information to support a kind historical linguistics, that is, tracing out the lineages of different languages. Through this work, Jefferson argued that Native Americans had occupied the continent for some time.

“By 1840, many politicians and social commentators had come to believe that the cultural differences exhibited by Indians and Africans on the one hand and Anglo-Saxon Americans on the other were rooted in biology…In their view, the different races of humanity formed a natural hierarchy topped by native-born, white [Anglo-Saxon] Protestants” (Patterson 2001:17). Recall that by this time, westward expansion was well underway, by both enslavers and those not dependent on slave labor, as was the immigration of Catholic Irish; a war with Mexico over control of western lands also loomed. Public interest in the identity of the Moundbuilders was high. Who was responsible for building the massive mound complexes, such as those now preserved at the Hopewell Culture National Historic Park and Etowah Indian Mounts Georgia State Historic Site, that were found throughout the eastern third of the North American continent? Were these constructed by a semi-civilized group that had since disappeared or were the ancestors of Native inhabitants responsible? The first publication issued by the newly established Smithsonian Institution was devoted to this topic.

Lewis Henry Morgan (Seneca land-claim and railroad lawyer; 1818-1881), along with his English contemporaries Edward Tyler and Herbert Spencer, were other “armchair anthropologists” who depended on correspondence from primary observers to craft their arguments. Morgan assembled a formidable data set of terms used to refer to kin (father, mother, sister, brother, and so forth) from throughout the Americas and parts of Asia. For example, in some society’s the same word refers to both “mother” and “mother’s sister.” He documented kinship structures that were shared between North America and southern India, arguing for an Asiatic origin of Native Americans.

In the end, Morgan argued for a single, but diverse human species. Physical differences in appearance were less important, differential “social development” more important. Thus, he extended Charles Darwin’s (On the Origin of Species; 1959) arguments about biological evolution to formulate a version of social evolution. In contrast to physician Samuel George Morton (a polygenist who argued for multiple creation events, one for each race; 1799-1851), he recognized no differences per se in the mental or physical capabilities of the races. In Ancient Society (1877), Morgan tied social and political organization to the form and scale of food production and its territorial requirements. As subsistence changed, owing to fluke innovations and borrowings from others, then so did social and political organization. Society evolved from an hunting-and-gathering stage, with small kin-groups and a somewhat flexible attachment to territory (which he termed “savagery”); to a stage of territory-based agriculture (termed “barbarism”); and, then to an urban society dependent on advanced agriculture and trade (termed “civilization”). Morgan provided examples of each stage, drawing from cultures known historically or via ethnographic (that is, first hand descriptions of human practice) accounts. Morgan’s ideas inspired Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels as they crafted their treatise on The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State: in the Light of the Researches of Lewis H. Morgan (1884).

Towards the end of what Thomas Patterson (2001) refers to as the “New Republic period,” institutions such as Smithsonian Institution (founded 1846) the Harvard University’s Peabody Museum of American Archaeology and Ethnology (founded 1866), and the U. S. Geological Survey and Bureau of American Ethnology (founded 1879) assumed the critical roles of collecting, interpreting and legitimizing information about Native Americans and other peoples. Each of these institutions played a major role, with the Bureau of American Ethnology, for example, establishing that the North American mound complexes were owed to ancestors of contemporary Native Americans (Thomas 1894).

Into the “Liberal Age,” new questions became important. The American frontier had closed, new industrial centers populated the east, and new immigration from southern Europe was underway. Native American dispossession continued, the US federal government arguing that because Native Americans had not improved the land, converting from wilderness to agricultural fields, their claims to land were vacated. Laws restricting immigration of Chinese people and of Catholics were enacted as were laws restricting employment options for Blacks. Anti-Semitism was also rampant by this time (Patterson 2001: 44-45).

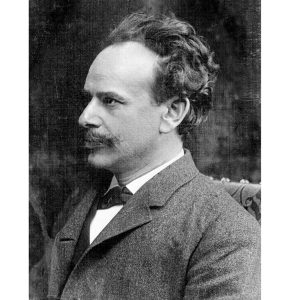

This is the environment into which Franz Boas, a Jew fleeing anti-Semitic policies in Germany, found himself when he immigrated to America to take a position at Columbia University. Boas was staunchly opposed to the idea of biology shaping culture, certain cultures being more developed than other, and the idea of human races–Boas was the first anthropologists to put the term in quotes. Boas knew from his explorations in Canada living among the Baffin Island Inuit and his studies in German, not to mention being a German Jew, that the claims of people like Morgan and Morton were decidedly untrue. The data did not support their claims. These presumed patterns in culture were not found in the societies he studied. Instead, a better understanding of cultural differences was to be attributed to their social environments, a concept he called historical particularism. . Boas attributed similar cultural patterns or behaviors to diffusion–sharing ideas with other cultures that came into contact–or some accident that had two cultures come up with the same idea. To further his claim for historical particularism over cultural evolutionists, Boas advocated for fieldwork, living and working in the location of the people you are studying.

Boas next set out to disprove the idea of so called “races.” His own backyard of Manhattan was the perfect field sites, as many immigrants came through Ellis Island. Boas took measurements of immigrants’ facial features and heads, as well as making casts of their faces. Through his work, he showed that physical differences between humans were due to nutrition and environment, and not biology. Thus, there was no biological basis for race. He used this data to combat the racism of the time, touting data over ideology.

In addition to these contributions to the field of anthropology, Boas was a prolific mentor. His work inspired his students to go out into the world and collect data to challenge supposed notions of human behavior, studying the history, language, physiology, and beliefs of their communities (the four subfields). He trained many famous anthropologists, including Alfred Kroeber, Margaret Mead, Zora Neale Hurston, Edward Sapir, and Elsie Clews-Parsons, many of whom went on to establish anthropology departments at other American universities. For these reasons, he is known as the father of American Anthropology. Boas and his students’ work defined the schemas of the “Search for Social Order,” and “Postwar Era” anthropology.

Around the same time that Boas and his students were conducting fieldwork, Bronislaw Malinowski, a Polish-born anthropologist, gets stranded in the Trobriand Islands. Malinowski, who was attending the London School for Economics and studying ethnology, planned to visit the Islands for a short time and learn about the peoples living there. Then history intervened. Malinowski had to prolong his stay on the island as World War I broke out and Britain declared war with the Austro-Hungarian Empire. As a subject of Austria-Hungary, Malinowski was at risk of internment, so was unable to return to Britain. Malinowski made lemonade out of the lemons he was handed, living, working, learning, and coming to respect and admire the Trobriand Islanders. He developed the concept of participant-observation, the hallmark of cultural anthropology, which involves living and working with while learning from the people you are studying, so as to be accepted by them and better understand their culture. Malinowski and Boas’ students used this method of data collection to write ethnographies, written observational science which provides an account of a particular culture, society, or community.

As the discipline of anthropology grew in America from the creation of departments by Boas’ students, it was also influenced by social changes. The Civil Rights Movement, Women’s Rights Movement, American Indian Movement, Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Rights Movement, as well as the Labor Rights Movement influenced the discipline, forcing anthropology to reckon with its past. These social changes brought more women and historically underrepresented groups into the academy, leading to new methods of inquiry and hearing from voices in field and in other cultures that had be overlooked and silenced by predominantly white, male, heterosexual scholars from the West. These changes ushered in the “Neoliberal Era I.”

The 2000s to the present find us in the “Neoliberal Era II” where Anthropology seeks to find it’s place against growing anti-intellectualism and inequality. This has lead to the rise of public-facing publications like Sapiens and Peeps Magazine, as well as a proliferation of podcasts where some anthropologists argue the importance of the field and how we can solve the various social problems we all face. It is also a harkening back to the time of Boas when anthropologists wrote for the masses, as Margaret Mead regularly wrote columns for women’s magazines and Zora Neale Hurston published works of fiction based on her fieldwork. Different from this historic time is also the rise of anthropologists employed in a wide range of fields, including the growing sector of UX, user-experience, where anthropologists apply their methods and theories to the world of business. While in this second era of neoliberalism, we still seek to answer the same question of “what does it mean to be human?” that led Ibn Khaldūn to compile his manuscript.

| Patterson (2001) Schema | Questions | Social/Political Climate | Data Collection | Demographics | Institution |

| New Republic (1776-1879) | One race or many?; hierarchy of races? | National identity formation; Westward expansion; justify slavery | Observations on subsistence mode; language; mounds and architecture; kin terms reported to synthesizing aggregators (“arm chair observers”) | Government agents, clergy and other professionals | Smithsonian Institution; Bureau of American Ethnology |

| Liberal Age (1879-1929) | Why human diversity? Why racism? | Industrial expansion, WWI | Museum supported expeditions | Professional anthropologists, with some training of the stigmatized Other (e.g., immigrants, women, Native Americans) | Museum and University departments of ANTH form |

| Search for Social Order (1929-1945)

|

Why are communities structured as they are? Why inequities?

|

Depression, WWII | Fieldwork by anthropologists; Participant observation | Anglo-Saxon working classes | US Government programs |

| Postwar Era (1945-1973) | How does the social environment influence the individual? | Decolonization begins; Humanistic Science prevails; Cold War funding to understand Soviet Union | “Big Science” area studies projects (Virú Valley, Puerto Rico, Micronesia) with participant observation | Italian, Irish, Jewish working classes | Expansion of universities with stand-alone ANTH departments |

| Neoliberal I Era (1975-2000)

|

How are people connected? How can we correct past injustices?

|

Declining support for higher education; rise of the individual

|

Participant observation | 1990s: Professoriate includes more women | Corporations and businesses; US Government add archaeologists for compliance with heritage laws; democratization of technology |

| Neoliberal II Era (2000-2020) | How can people persist in a capitalist world system? | Anti-intellectualism; population displacement fueling nationalism | Indigenous collaboration | Professoriate includes more “minorities” | Expansion of NGOs; democratization of technology |

What’s Next?

So now that you made it to the end of the chapter and are enrolled in this class, what are you in for? You’re in for the story of our species, Homo sapiens sapiens. The story of how we got to this moment in time, where we came from, and the rich diversity of the ways we can be human. This story isn’t always easy or happy, as Michael Wesch reminds us:

Anthropology is not only the science of human beings, but also the art of asking questions, making connections, and trying new things. These are the very practices that make us who we are as human beings. Anthropology is the art of being human. This art is not easy. You will have to overcome your fears, step outside your comfort zone, and get comfortable with the uncomfortable. (https://anth101.com/humanintro/)

But at the end of it, you might just learn a little bit more about yourself, why you believe what you believe, develop a greater appreciation for diversity, and see the world in a new way. Let’s get started!

Key Takeaways

- Anthropology is the study of people throughout place and time. Unlike the other social sciences, it is holistic, meaning it combines the biological, cultural, and environmental to understand humans.

- There are four subdisciplines of Anthropology: cultural, linguistic, archaeology, and biological.

- The roots of Anthropology begin in the 1300s, but the discipline became formalized in the 1800s by Morgan and Tylor, and American Anthropology has its beginnings in the 1900s.

"science of the natural history of man," 1590s, originally especially of the relation between physiology and psychology, from Modern Latin anthropologia or coined independently in English from anthropo- + -logy. In Aristotle, anthropologos is used literally, as "speaking of man." (source).

thought to be different from the group and, because of those differences, possibly inferior and even dangerous.

those raised in Western, Educated, Industrial, Rich, Democracies. WEIRD people are highly individualistic, self-obsessed, nonconformist, and analytical.

those raised in non Western, Educated, Industrial, Rich, Democracies, who think of themselves as members of communities , instead of emphasizing the individual

The anthropological concept that argues the whole is greater than the sum of the biological, historical, cultural, social, historical, or material aspects of being human. All of these are interconnected and one cannot be understood without also considering the other.

One of the four subfields of anthropology; the study of materials to learn about people, behaviors, cultures, and institutions, often from the past

one of the subfields of anthropology that focuses on the human body, its genetic history, how it varies owing to history or environment, how it is affected by cultural practice.

a hybrid specialization in anthropology, which combines archaeology and biological anthropology, studying ancient human remains to learn about past behaviors.

a hybrid specialization, which involves application of archaeological methods to biological anthropology in investigations of a crime scene in order to identify evidence and reconstruct crime scene, usually a murder.

one of the four subdisciplines of anthropology; Cultural anthropology focuses on the diversity of behaviors and beliefs of living people

one of the subdisciplines of anthropology; focuses on the study of language--how it evolved in humans, how it changed historically, and how language is used by different subgroups and in different contexts today.

a type of anthropology (can be from any subdiscipline) that addresses real world problems using anthropological methods and theories

prehistoric, Indigenous inhabitants of North America who, during a 5,000-year period, constructed various styles of earthen mounds for religious, ceremonial, burial, and elite residential purposes

early anthropologists (like Lewis Henry Morgan, Edward Burnett Tylor, and Herbert Spencer, who did little, if any fieldwork, to learn about other cultures, but inside relied on the first-hand accounts of explorers and missionaries to compile information about other cultures

someone who subscribes to the ideas of polygenism, the belief that human so called "races" emerged from different origins, as opposed to those who subscribe to monogenism, the idea that all "races" have a common origin

The idea that each culture has its own particular and unique history that is not governed by universal laws and must be understood based on its own specific cultural and environmental context, especially its historical process.

the branch of anthropology that compares and analyzes the characteristics of different peoples and the relationships between them.

living and working with while learning from the people you are studying, so as to be accepted by them and better understand their culture

written observational science which provides an account of a particular culture, society, or community.

The economic and social shift towards free market trade, deregulation of financial markets, mercantilism and away from state welfare provisions and social safety nets