2 What is Culture?

Taylor Livingston

Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you should be able to:

- Define culture.

- Compare cultural relativism, moral relativism, and ethnocentrism with examples of each.

- Describe emic vs etic perspective.

- List and explain the six aspects of culture.

Culture Some Definitions:

The first widely accepted notion of what exactly is culture was compiled by Edward B. Tylor. Tylor, a Quaker, school dropout, and British man who kept a fantastic beard throughout his life (see image), is often considered the father of cultural anthropology. He became interested in other cultures because he was encouraged to travel to warm climates for his tuberculosis. While this did nothing for his tuberculosis, it did a great deal for anthropology. Tylor traveled to Mexico and wrote about its peoples (Lowie, 1917). From his experiences in Mexico and studies of other societies as a professor at Oxford (though he had no degrees), he compiled a definition of culture: “A complex whole, which includes knowledge, belief, arts, morals, law, customs and other capabilities and habits acquired by people” (Tylor, 1871, p. 1).

From this first definition, the concept of culture has been expanded to include:

- Learned behaviors and symbols that allow people to live in groups.

- The primary means by which humans adapt to their environments.

- The way of life characteristic of a particular group of humans.

Examples of the first bullet include that official language (a collection of symbols) of the United States is English, which allows us to communicate. We share common symbols, such as a bright, red octagon that we have learned means “stop” that enables us not to crash our cars into each other. While an example of the second bullet is that we do not adapt to winter in Nebraska by increasing our stores of brown fat like other animals do, nor do we develop thicker hair on our bodies, like our cats and dogs do. We adapt by cultural means: we put on a coat, scarf, and mittens for outside and turn on the heat in our homes. The final bullet is a little trickier. What is “a way of life”? It’s all the bullet above, plus the knowledge and beliefs Tylor mentions. If we take football fans of the University of Nebraska-Lincoln as a particular group of people, what might be some of their “ways of life”? Perhaps, it would include: wearing red or black clothing on game days with the word “Nebraska” or the symbol “N” on it, tailgating (consuming alcohol for those over 21 and eating all the things dipped in ranch dressing) in the parking lot of Memorial Stadium, gathering in the Railyard to watch the game, cheering when the players take a diamond-shaped ball across a large field into the opponent’s territory, and hearing a cannon sound when they do.

The Concept:

While definitions and examples of the parts of the definition may be easy to understand, the concept of culture can be difficult to grasp. Most likely because unless you have ever travelled out of the country or to a vastly different area of the country, you have not spent much time thinking about how the way you believe and how you do things are unique to a specific part of the world. This leads some Anthropology textbooks to compare the concept of culture to the water in which a fish swims. Sure, this is an apt analogy as most of us are unaware of the extent culture surrounds us and shapes our lives and we cannot live without it. But, culture has moral and historical underpinning that are not quite captured by the fish in water analogy. As a result, the example of American barbeque to illustrate the concept of culture and its six aspects:

Six Aspects of Culture

- Learned—taught by someone to someone else, usually parent to child. This process is called enculturation.

- Shared—groups share norms—the way things ought to be done—and values—what is true, right, and beautiful

- Symbolic—culture creates meaning; it is the story we tell ourselves about ourselves

- Patterned—practices make sense; culture is an integrated system—changes in one area, cause changes in others

- Adaptive—culture is the way humans adapt to the world; current adaptations may be maladaptive in the long term

- Changes—culture constantly shifts and transforms; it is not static

Barbeque: More American than Apple Pie

When referring to American barbeque, it is not hamburgers and hotdogs cooked on a gas grill, but meat cooked “low (over an indirect flame) and slow” (at least eight hours and as long as 18!). Legend has it the term “barbeque” comes from an Indigenous group, the Tainoused, from the Caribbean who likely cooked fish for an extended time over a wooden pit made with green wood (so as not to catch on fire) called a “barabicu” (or “sacred pit” in the Taino language). Christopher Columbus observed the practice and took stories of it back to Spain where the term became “barbacoa” (KM, no date; Suddath, 2009). Another Spaniard, De Soto, notes that around 1540 near what is now known as the state of Mississippi, he observes the Chickasaw roasting a pig over a “barbacoa.” Eventually, the practice of cooking meat “low and slow” makes its way to the American colonies and becomes known as “barbeque” (Geiling 2013; Suddath, 2009). This way of cooking meat lasts longer than British rule, as parties serving barbeque were held for several days, celebrating the conclusion of the Revolutionary War (KM, no date).

The practice of barbequing meat becomes most popular in the Southern states. Pork was the first meat used in this cooking practice, as pigs could be left free to roam and feed in the temperate Southeastern forest, while cows needed large amounts of cleared land, enclosures and feed. It is thought that barbeque would have been the preferred method to cook pigs because of the lean, tougher meat forest living and foraging would engender. By barbequing the pigs, the meat would become “fall off the bone” tender (Gieling, 2013).

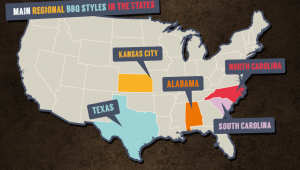

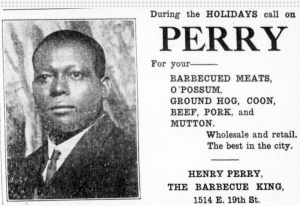

The South’s immigrants largely influenced the seasoning and dressing flavors of the meat. Early British settlers to the Colonies taste for tart seasoning likely influenced the vinegar-based seasoning of barbeque in Virginia and North Carolina, known as Carolina-style barbeque today (Gieling, 2013). This was likely the type of barbeque eaten at the celebrations following the winning of Revolutionary War and mentioned by George Washington as taking place on his plantation (KM, no date). In South Carolina, the large number of German and French immigrants influenced the addition of mustard to the vinegar sauce of barbeque. While in Memphis, access to a large port on the Mississippi River, created the “Memphis style” of barbeque, known for tomato-based barbeque sauce sweetened with molasses, which was imported from the Caribbean. Westward expansion brought the practice of barbequing to Texas, where German immigrants used the practice on their vast supplies of cattle, creating the Texas style of barbeque still around today. The Kansas City style of barbeque, which is the most common style of barbeque (what most people consider barbeque sauce—think about what you would receive at McDonalds, Burger King, or Chick fil A if you asked for barbeque sauce—it’s that style), blends the Texas tradition of using beef with the Memphis style of a sweet and tangy sauce (Gieling, 2013). Kansas City owes its unique blending of styles to Henry Perry, an African American man from Memphis who adapted his home city’s style of barbeque to the large beef meat packing industry in Kansas City when he moved to the area in 1907 (Gieling, 2013).

Indeed, people of African descent have a long connection to the practice of barbequing as the likely cookers of much of the pork-based barbeque consumed in the Southern Colonies and later states were enslaved Africans. Later, many African Americans, like Mr. Perry, took this cooking tradition with them as they migrated out of the rural South to Northern and Midwestern cities during the Great Migration. By the middle of the 20th century, every city in the US had an African American owned and operated barbeque restaurant, cementing the connection between barbeque and African American culture (Suddath, 2009).

Which style of barbeque one prefers is very contentious, especially in the American South, and often a result of what style is most familiar. For example, I am from South Carolina and have been eating mustard-based barbeque for most of my life. When I attended graduate school in North Carolina, I did not understand how people were referring to the almost pure vinegar concoction the shredded meat was in as “sauce.” This was decidedly “wrong” in my opinion. Vinegar is an ingredient to a sauce, not THE sauce. Plus, a sauce is closer to a solid than a liquid! Similarly, when visiting Birmingham, Alabama, I was severed their version of barbeque sauce. While closer to an actual sauce than North Carolina style, it was mayonnaise-based! Surely, one cannot get more wrong than THAT!

The story of barbeque tells the story of America. From its origins in the Caribbean, witnessing in Indigenous cuisines to sauces based on immigrants’ tastes, and finally, it’s popularization through African American-owned restaurants, barbeque symbolizes the melting pot of America and illustrates the concept of culture. The practice is rooted in history, and what style of barbeque one believes to be the best depends on from which region they hail. Further, the story of barbeque illustrates the six aspects of culture:

Barbeque and the Six Aspects of Culture

Barbeque practices are learned:

Like culture, what iteration of barbeque is THE type of barbeque (Carolina, Memphis, Texas, or Kansas City style) is learned by children through the cooking or consumption practices of their parents.

Barbeque is also shared:

Whether you are in Newberry, SC or Charleston, SC, you know that when someone is serving barbeque, it is mustard-based.

Barbeque practices are patterned:

The Texas style of barbeque using beef instead of pork makes sense due to the large number of cattle ranches in the area; what happens in one area (economic) is also found in another (foodways).

Barbeque is symbolic:

For many African Americans during the Great Migration, barbeque was a symbol (a short hand call back) to home and family–way to keep family and regional traditions alive in a new area.

Barbeque is adaptive:

The first Southern Colonists used pigs for barbeque because they were readily available in the area, applying the barbeque technique made this meat edible and a useful resource.

Barbeque practices change:

The addition of mustard to the sauce by South Carolina French and German immigrants changed the barbeque recipe to fit their pallet, based on the cuisine of their countries of origin.

Finally, my last paragraph on mustard-based barbeque sauce being the best and the standard by which other styles should be measured, is related to another aspect of culture—ethnocentrism, the idea that your culture’s way is the best way and every other way is wrong. This concept is what anthropologists try to argue against. Instead, anthropologists argue for us to practice cultural relativism when exposed to new ideas or practices. Cultural relativism is the opposite of ethnocentrism. Cultural relativism argues that the beliefs, values, and practices should be understood based on that culture’s reasoning and history, and not be judged against the criteria of another culture. Using our barbeque example, a cultural relativist would try all the different types of barbeque and attempt to understand the different styles based on the history and practices of the region. They can have a favorite style, but they do not think their favorite style is the best or only way to prepare meat.

Another form of relativism is moral relativism, which argues there is no universal system of right and wrong. What is considered “right” or “wrong” depends on the context (is relative) that that particular culture or historical time period. A moral relativist would argue there is no such things as universal human rights. Using a barbeque example, a moral relativist would argue the best and only way to prepare barbeque is whatever that region thought was the best, even if they murdered people to make the barbeque. If people in that region did not seeing murder and cannibalism as morally or ethically wrong, then it was not wrong. Anthropologists are not moral relativists, as all ascribe to a code of ethics (links to external site) that guide their practice based on the idea of universal human rights (links to external site) as set forth by the United Nations. While anthropologists may study groups, who practice cannibalism or female genital cutting, they do not believe these practices are morally or ethically correct. Instead, they attempt understand the culture’s reasons for such practices and not use their own culture’s standards and values in their evaluation.

The differences in ways of understanding cultural practices, whether from a perspective of someone of that culture or from someone outside of that culture bring us to the concepts of emic and etic perspectives. An emic perspective is the insider’s (how members of the culture) view and understanding of that culture’s practices, while an etic perspective is the outsider (how people who are not members of that culture) view and understand that culture’s practices. Consider these tweets from two different news sources:

Both are about banning the halal and kosher practice of slaughtering animals without stunning, but use different images with different connotations to illustrate this point. Why might that be? First, more information on the differences in animal slaughter is necessary: The halal method of slaughter requires an observant Muslim (someone who practices Islam) to slaughter the animal using a sharp knife to cut the arteries in the animal’s neck to maximize blood loss and swiftly kill the animal. The practitioner must say a blessing before the slaughter. The animal’s head must be facing toward Mecca. The kosher method is similar, also requiring a sharp knife to cut the arteries of the animal’s neck and the stating of a blessing by someone who is Jewish (Aghwan and Regenstein 2019). The stunning method shocks the animal into unconsciousness before slaughter and uses different bleeding and cutting techniques to maximize blood loss. So which of these different methods is considered less harmful to the animal—stunning before slaughter or a swift cut to the main arteries? For many years, animal rights supporters have argued stunning is a more humane method, which led Belgian to pass a law excluding the religious exemptions of halal and kosher slaughter methods. While most halal slaughters do stun the animal before cutting, most slaughters making the meat kosher require that the animal not be stunned. Thus, the issue arises for the minority of halal slaughters not stunning the animal prior and most Jewish slaughters requiring the animal to not be stunned for the meat to be deemed kosher.

The tweets use of different images, one of a meat market and the other of sheep being slaughtered, speak to the different perspectives on this issue. Al Jazeera is a Middle Eastern based news media company, many of their audience practicing Islam, while the BBC is a European-based news media company, with many of their audience not practicing Islam. Al Jazeera may be demonstrating an emic perspective, portraying the court’s ruling of the ban with the image of a meat market to signal the normalcy of halal practices, while the BBC displays a gorier photo of halal slaughter to possibly signal brutality of the non-stunning methods, an etic perspective.

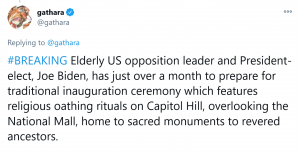

Another example of the etic perspective comes from a tweet by Patrick Gathara, a Kenyan reporter, cartoonist, and satirist:

As Gathara is not American, he reports on the American cultural practice of inauguration from an outsider, etic, perspective, referring to Joe Biden as an “opposition leader” and the ceremony as a “religious oathing ritual” and Washington DC as “home to sacred monuments to revered ancestors.” Nonetheless, Gathara’s description is not technically incorrect: Biden won the Presidency by defeating the incumbent, Donald Trump, making him the opposition; inauguration does have a religious element as US Presidents swear the Oath of Office on a Bible; and the National Mall does contain monuments to ancestors like the Lincoln Memorial, honoring Abraham Lincoln. However, the description does depict the ceremony of inauguration as strange, using terms (“opposition”, “religious”, “revered ancestors”) usually reserved for describing the practices of faraway, remote, Indigenous peoples, not practices of most powerful country in the world. This is not how someone who was American would describe the swearing in of the new President of the United States. This exactly Gathara’s objective as his Twitter account presents US and other Western nations’ news using the etic perspective (which is often derogatory and distancing/othering—see the BBC tweet’s image above to non-Western nations). How one views certain practices, depends on the perspective they are taking, be that emic or etic, ethnocentric, or culturally relative.

An anthropological perspective seeks to combine the emic and etic perspectives. It understands culture practices in a culturally relative way, which views culture as patterned, learned, shared, symbolic, adaptive, and ever-changing.

Key Takeaways

- What anthropologists call “culture”, knowledge, beliefs, and practices of a group of people, is all around us, but it can be difficult to see and understand because it shapes how we see the world.

- Viewing cultural practices from the insider’s perspective with a knowledge of context and history like that of a fish in water, is taking an emic view. Believing that your culture’s way of doing things is the only and best way to do things is called ethnocentrism.

- Culture is learned—taught by someone to someone else, usually parent to child. This process is called enculturation.

- Culture is shared—groups share norms—the way things ought to be done—and values—what is true, right, and beautiful

- Culture is symbolic—culture creates meaning; it is the story we tell ourselves about ourselves.

- Culture is patterned—practices make sense; culture is an integrated system—changes in one area, cause changes in others.

- Culture is adaptive—culture is the way humans adapt to the world; current adaptations may be maladaptive in the long term.

- Culture changes—culture constantly shifts and transforms; it is not static.

- Anthropologists use all these aspects of culture to try to understand the practices of another culture, which is called cultural relativism.

References

Geiling, N. (2013, July 18). The Evolution of American Barbecue. Retrieved December 18, 2020, from https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/the-evolution-of-american-barbecue-13770775/

KM (no d). The History of Barbecuing. Retrieved December 18, 2020, from https://www.foodnetwork.com/fn-dish/news/2019/6/the-history-of-barbecuing

Lowie, R. (1917). Edward B. Tylor. American Anthropologist, 19(2), new series, 262-268. Retrieved December 17, 2020, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/660758

Suddath, C. (2009, July 03). Barbecue: A Brief History. Retrieved December 18, 2020, from https://time.com/3957444/barbecue/

Aghwan, Z. A., & Regenstein, J. M. (2019). Slaughter practices of different faiths in different countries. Journal of animal science and technology, 61(3), 111–121. https://doi.org/10.5187/jast.2019.61.3.111

Tylor, E. B. (1871). Primitive culture: Researches into the development of mythology, philosophy, religion, art and custom (Vol. 2). J. Murray.

cumulative deposit of knowledge, experience, beliefs, values, attitudes, meanings, hierarchies, religion, notions of time, roles, spatial relations, concepts of the universe, and material objects and possessions acquired by a group of people

evaluation of other cultures according to preconceptions originating in the standards and customs of one's own culture.

the notion that the beliefs, values, and practices should be understood based on that culture’s reasoning and history, and not be judged against the criteria of another culture

the concept that argues there is no universal system of right and wrong. What is considered “right” or “wrong” depends on the context (is relative) that that particular culture or historical time period

the insider’s (how members of the culture) view and understanding of that culture’s practices

the perspective of the outsider (how people who are not members of that culture) view and understand that culture’s practices