8 Forensic Anthropology – A Brief Introduction

A Brief Introduction

Bill Belcher

Learning Objectives

At the completion of this chapter, the student will:

- Understand the outgrowth of forensic anthropology from biological anthropology;

- Understand basic questions forensic anthropologists examine in terms of skeletal materials;

- Be able to state the best practices in determining a biological profile;

- Understand the use of forensic odontology;

- Understand use of DNA analysis in forensic anthropology;

- See the interface between forensic anthropology/archaeology and investigation of human rights violations.

Introduction

Biological anthropology is a unique discipline that has contributed much to forensic investigation over the last two centuries. Biological anthropologists study biological evolution, genetic inheritance, human adaptability and variation, primatology, primate morphology and the fossil record of human evolution. Forensic sciences, including forensic anthropology, are becoming more and more popular due to various television dramas, novels, and movies. This section gives a more detailed overview on forensic anthropology and forensic odontology (or dentistry).

What is forensic anthropology?

Forensic anthropology is the application of human biological anthropology and its techniques to assist in the investigation of human (and often non- human) remains in order to provide more information to a medical examiner or coroner’s office. The investigation of human skeletal materials answers many questions about what may have happened to a person or group of people. While a forensic anthropologist cannot give a legal opinion on the CAUSE of death, they do offer information that can be used to understand the mode or manner of death.

Mode and Manner of Death

While the cause of death can be tied to many different contributing factors, the primary cause of death is failure of the heart to supply the amount of blood flow necessary for life. Of course, this may be related to drugs, trauma, disease, etc. But only a medical examiner (or coroner in some jurisdictions) can make that legal definition in most jurisdictions. However, forensic anthropologists can use evidence of skeletal trauma and condition to understand the mode of death. There are five different modes (manners) of death: natural, suicide, homicide, accidental, and unknown. These are general definitions and specific jurisdictions may differ from those discussed here.

Natural refers to conditions that are naturally occurring and are usually related to age or disease. Suicide refers to those deaths that are related to a victim causing their own death through either direct or indirect means. Homicide refers to a victim’s death related to the direct and deliberate actions of others. Accidental refers to deaths that are related to various causes that cannot be related directly or indirectly to specific individuals. Finally, unknown refers to those deaths that are related to factors that cannot be determined.

What can a Forensic Anthropologist tell death investigators?

The information that can be provided by the forensic anthropologist can be illustrated in the form of questions. The answers to those questions are used to develop a biological profile of the victim, along with other relevant records, such as medical and dental records. A biological profile is the reconstructed life and death of the individual, including biological sex, chronological age, antemortem (before death) trauma, ancestry, and stature.

Are these remains human? Most of the remains that are seen by a forensic anthropologist are usually animal bones found by responsible citizens who turn them over or report these remains to the local police. Most mammals have the same general type of bones and many do look alike (even a trained forensic anthropologist may mistake a skeletonized bear paw with a human hand). Many forensic anthropologists either rely on colleagues who have training in comparative osteology or faunal (animal) analysis; some forensic anthropologists may even have extensive training in the identification of animal bones. Additionally, through the analysis of bone histology (its microscopic structures), we can examine the type of bone and its structure. Human and non-human bones differ in their structure.

How many people are represented? Mammals have what is called a “bilateral (or paired) skeleton.” This means that mammals have a left side and a right side. Because of this situation, it is possible to distinguish bones from different sides of the body (for example, while the left and right humerus are similar, we can tell which side they came from based on the different orientations of the bone itself). Forensic anthropologists can count the number of left and right bones of the same kind (left and right femora or thigh bones for example) and see what the minimum number of people (Minimum Number of Individuals or MNI) are needed to account for this number. Other sources of information that can be used to get a better idea of the MNI are bone size, age, and general condition).

What is the biological sex of this person? One of the most important aspects of the skeleton that need to be ascertained is the biological sex of the individual. This differs from the gender of the individual as gender may refer to outward sexual attitude, characteristics, clothing, and behavior while, in general, biological sex is usually male or female (there are some exceptions to this, of course). Primarily the differences between males and female are manifest in the pelvic region (this should go as no surprise as the female pelvis has evolved to birth a large-brained child as well as walking erect) as well as musculature marks on bones such as the femur (upper leg) and occipital/nuchal (neck) region of the skull.

What is the Biological Profile?

- Is this human?

- How many people are present?

- What is the biological sex?

- What is this person population affinity?

- How old is this person?

- How tall is this person?

How old was this person? People change as they age. We can usually look at a person and see what age, even generally, they are. This same situation occurs in bone tissue. By looking at different bones, we can get a general idea of the age of a person. Up until around age 25, we look at growth of tissues, like long bones of the arms and legs. As we get older, those bones get longer because they are actually composed of three or more pieces (mostly the two ends on a shaft of bone). As we age, those bones grow and when we get to a certain age, the pieces fuse together and no longer grow. This age is different for males and females as well as different ethnic populations. After about age 25, we are looking at degeneration or damage to bone tissue. This wear-and-tear on bones can be calculated and give us a rough idea of the age of the individual.

Important bones for this include the hip bones (pelvic girdle or os coxae), especially where the two sides of the hips rub against each at the pubic symphysis near the front of the pelvic girdle or the sides where they articulate (connect) with the sacrum, the lowest part of your spine that is your “tail bone”.

What was this person’s population? Most modern biological anthropologists don’t use concepts such as “race” because they recognize variation in the human appearance (phenotype) as a continuum. “Race” or “ancestry” are specific social concepts that are applied and related to appearance, religious, as well as economic settings. However, forensic anthropologists routinely use this concept in discussing skeletal remains because “race” is a social concept and used in today’s society to describe individuals. Thus, if we have a missing person’s report and we are attempting to identify possibilities, we have to use these concepts. For example, if we have a report that says an individual is “white” – we must be able to distinguish this, if possible, based on skeletal information. A lot of research in forensic anthropology has been focused on defining these socially-defined characteristics as they may appear in bone tissue. However, we can also begin to examine geographic populations in terms of origin. However, there is as we are writing this textbook (in early 2021) major changes being made in how we practice forensic anthropology in terms of the appearance of the an individual. Phoebe Stubblefield of the C.W. Pound Laboratory at the University of Florida-Gainesville has suggested that we take a “decedent” approach. That is, how did this person (or their family or community) define themselves, what group (or lack of group) did they identify with as a person. This requires taking a more wholistic, cultural perspective and understanding the concepts of emic and etic.

How tall was this person? Basically, if a person has long bones, he or she was probably a tall person. But through research done over the past 100 years, we can take a measurement of a bone and determine with some certainty how tall that individual was. Of course, this varies based on ethnicity and gender. However, some bones are better to use for this analysis than others. Most of our height is related to the length of our legs, so it is better to determine the height (or stature) of an individual based on leg bones instead of arm bones (although this can be done – it’s just not as accurate).

What happened to this person? The analysis of marks on the bones can be related to an understanding of the trauma that was inflicted on the individual around the time of death (peri-mortem). This would included sharp-force trauma (knives, machetes, etc), ballistic trauma (gun shot wounds), blunt force trauma (hammer, etc.)

What about the teeth? Forensic odontology (or dentistry) includes the analysis of materials relat- ed to dentition in a legal setting. Three different aspects are the primary areas of interest: the estimation of age based on tooth development and growth, the analysis of various characteristics of teeth in order to identify specific individuals, and bite-mark analysis.

For aging, forensic dentists will examine the growth sequences of deciduous (not permanent) dentition and its replacement by permanent teeth. For identification purposes, forensic odontology is the preferred method of positive identification.

The comparison of after-death (post-mortem) radiographs (x-rays) with before death (ante-mortem) radiographs is the primary way of identifying specific individuals. While this will be dis- cussed more in a subsequent section, tooth restoration, including various types of fillings, caps, partial dentures, and dentures, may provide a point-by-point comparison of the shape of various restorations (fillings). Other forms of comparison include the shape of roots and pulp cavities.

Due to the individual shape of teeth as well as modifications that occur during life, primarily breakage, it is possible to identify someone based on bite marks. Bite marks are very personal lines of evidence that are often left on victims of physical and/or sexual abuse, particularly children. Thus, much of bite-mark analysis done by forensic odontologists is related to child abuse.

DNA in Forensic Anthropology

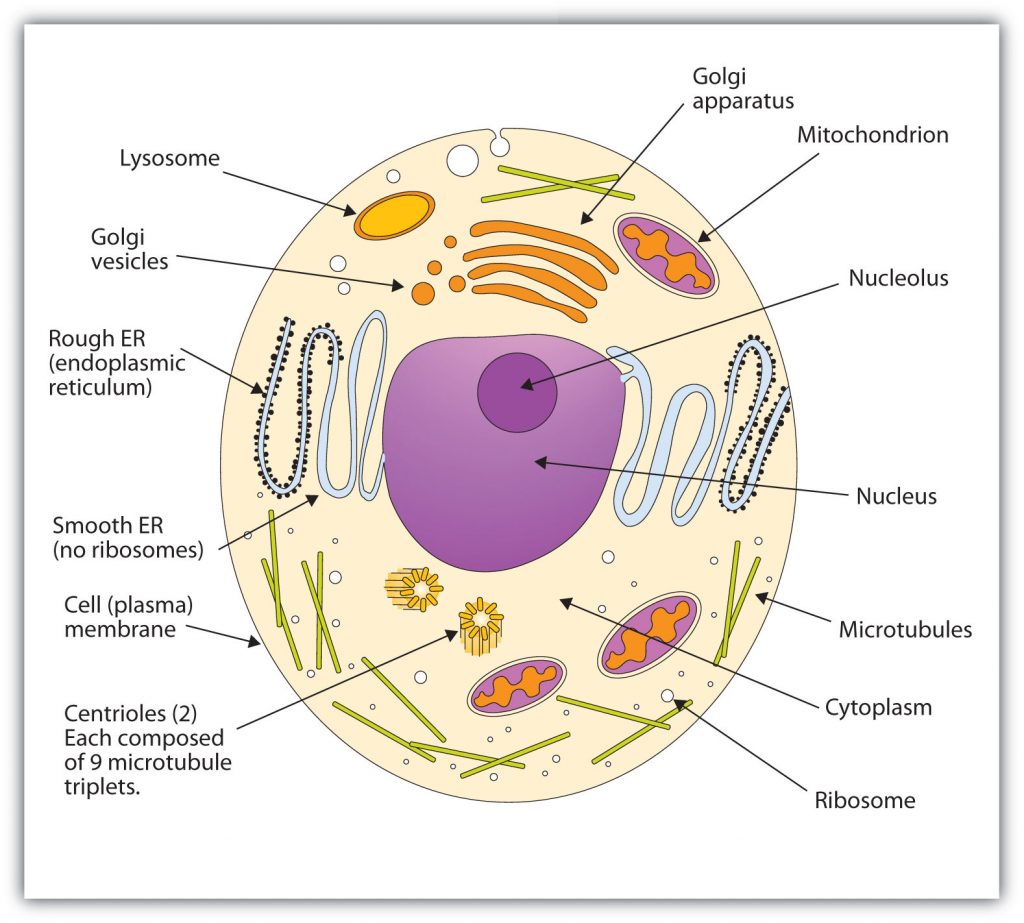

Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) analysis has been gaining more and more importance for the last several decades, with the first use of DNA profiling was done in 1985 with a United Kingdom murder case. There are three main forms of DNA analysis used in forensic (and archaeology, for that matter) that focus on different genetic histories or location of the DNA analysis. There are three major forms of DNA that are accessible in human cells: mitochondrial DNA, autosomal DNA, and y-chromosone DNA. The most commonly used form of DNA analysis in forensic anthropology is mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), which is focused on specific locations of DNA in the mitochondria. Mitochondria are found in all cells, but in the cytoplasm, outside of the nucleus, but inside the cellular membrane. Mitochondrial are only inherited from the mother (the matriline); although all cells have mitochondria (the so-called power house of the cell as they convert sugars and starches into energy for the life of the cell), the mitochondria of the sperm cell are contained in the tail, which breaks off during fertilization; thus, there is no contribution from the father (or patriline). mtDNA preserves well in unburned bone, so it is frequently used in archaeological material and forensic case work. Family reference samples for identification are gained through collection of appropriate matrilineal relatives. However, mtDNA sequences can be shared between siblings (acquired through the mother) or passed down to a female relative’s children. Thus, mtDNA doesn’t is not unique to an individual and can be shared with siblings as well as maternal ancestors and descendants.

Autosomal DNA (autDNA) is the DNA pattern found in the nucleus that determines who we are as individuals. This requires samples for comparison from both the mother and the father. With advancing DNA technology and appropriate samples, autDNA can provided a more unique, individual comparison. y-chromosone (yDNA) is very similar in approach to mtDNA, but focused on the patriline and male relatives. This form can be useful if no family reference sample comparison with the matriline (mtDNA) is possible.

Case Study: The First Battle of Makin Island, August 17, 1942

On August 17, 1942, 211 US Marines of the 2nd Marine Raider Battalion, under the command of Colonel Evans Carlson and Captain James Roosevelt (son of President Franklin D. Roosevelt) were land on Makin (Butaritari) Island from two submarines (USS Nautilus and USS Argonaut) that travelled from Pearl Harbor, O’ahu Island, Territory of Hawai’i. Their mission was to disrupt or destroy a Japanese sea-plane garrison that had between 83 and 160 men under the command of a warrant officer. An additional goal was to misdirect Japanese reinforcements to this small atoll away from the main object at Guadalcanal. In the aftermath of the battle, 30 individuals were declared Killed-in-Action/Body Not Recovered, with subsequent post-war findings that perhaps up to 9 of these individuals had been captured post-battle and imprisoned at a Japanese outpost on Kwajalein Island. These 9 prisoners were executed the following October 1942. After the battle, the surviving Japanese detailed a work crew of the local islanders to gather up the bodies of the US Marines and bury them in a large mass grave.

In May and November/December 1999, two US Army Central Identification Laboratory-Hawaii (USA CILHI, precursor of the current Defense POW/MIA Accounting Ageny: Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA). excavation teams investigated and tested areas of a possible mass grave containing the Marines that were killed in August of 1942. The December mission was successful and recovered 20 completed sets of articulated skeletal remains along with material evidence from the raid, including M1 Garand rifles, Mk 5 “pineapple” grenades, ammunition, walkie-talkies, identification tags, etc. The subsequent analysis took place at the Department of Defense’s military forensic/skeletal identification laboratory on the island of O ‘ahu, Hawai’i, just a few miles from where these men departed for the battle. Each of the methods discussed above was used to identify these individuals.

Our initial population of analysis included some outliers, but there were primarily Caucasian males, in their early twenties in age, and about 6 feet all. Anthropologically, it seems that these individuals would be generally indistinguishable. However, one individual stood out as physically separated (but still associated with the mass grave) in terms of associated artifacts (none) and geographic origin. This individual clearly was a local Pacific Islander; local oral history indicated an individual was killed for stealing saki from the Japanese during that battle and he was placed in the grave along with the US Marines.

The remaining individuals were identified using the biological profile, supporting artifacts, trauma analysis, and, most importantly, forensic odonotological comparison to the paper dental records. Two individuals stood out due to their biological profile, one was over 6′ 5″ tall and the other was older than 30 years of age. Their dental patterns also matched individuals with these biological profiles. The older individual was the Japanese linguist for the team and also exhibited a particularly type of wear on his front teeth from chewing a pipe stem. Photographs revealed him smoking a pipe and the remains of a pipe was recovered at the waist of this individual, probably tucked into his trouser waist during the battle. Thus, we had 17 individuals that needed identification; of those, the dental restorations were documented in their official deceased personnel files and allowed a positive identification of an additional 12 individuals. Five individuals could not be initially identified as they had identical biological profiles: Caucasian males, about 6 feet tall, in their early 20s, and with no dental records or no restorations (no records to assist in their identification or perfect teeth!). Thus, mtDNA was used to identify these individuals. But, two individuals had a similar mtDNA sequence.

How could that be? Well, if you remember from above, mtDNA is not an individuating DNA analysis and can be shared amongst siblings and maternal ancestors. While not common, this has happened several times with the military identifications and usually indicates some kind of familial relationship that was unknown (perhaps separated by decades). I’ve always thought that these individuals’ families originated in a common or nearby villages in Europe sometime in the past.

So, we had two individuals that still needed to be identified, but were “identical” in terms of dentition, biological profile, and mtDNA sequences! So, we went back to the personnel files and found that one individual had a tooth extraction just before getting on the submarines! We examined the tooth areas of both skulls: one skull had the tooth missing, but we had originally thought that it was a postmortem loss and wasn’t recovered. The boney area of the maxilla around the tooth indicated a healing response and thus, we identified this individual based on this occurrence as well as the presence of identification tags found near the body. The final skeleton was identified based on exclusion.

So, in the end, the USA CILHI identified one local islander (who was them repatriated) and 19 US Marines. So, we know that 9 individuals were captured, so this makes a total of 28 or slightly less. So what happened to any other Marines that are not accounted for? It is thought that perhaps three or four individuals (the counts of prisoners and others killed on Makin is a bit muddled) may have drown in trying to leave the island on the rubber rafts while trying to go over barrier reef in heavy surf.

Human Rights Violations and Forensic Anthropology and Forensic Archaeology

- Forensic archaeology developed as a discipline to assist in outdoor scene investigation as well as the investigation of mass graves that were investigated as part of the human rights violations and mass genocide/murder in Europe and Africa in the 1980s and 1990s. The expansion of forensic archaeology now looks at human rights violations in North America and Central America.

- In North America, a major form of forensic anthropology and archaeology is focused on recovery and attempted identification of the undocumented immigrant deaths when crossing in the desert regions between Mexico and the United States in addition to the Gulf area and Caribbean in the US Southeast. Hostile Terrain 94 is a travelling, participatory “art” exhibit that focused on these deaths, https://sgis.unl.edu/hostile-terrain-94.

- Information on basic human rights can be found at https://www.un.org/en/universal-declaration-human-rights/index.html and https://www.icrc.org/en/war-and-law/protected-persons/missing-persons.

Key Takeaways

- Forensic anthropology is the use of bioanthropological techniques to reconstruct the biological profile of an individual in terms of identification (age, geographic origin, stature, biological sex as well as determine minimum number of individuals present, how long has this person been dead, and are these materials human or not;

- Forensic odontology is the study of human dental remains and comparison to known dental records to establish a legal and positive identification; this is usually done by trained dentists;

- While information related to trauma can assist, a medical professional usually makes a legal determination of cause of death;

- Different forms of DNA (mitochondrial DNA, autosomal DNA, and y-chromosome DNA can be used to substantiate an biological profile;

- Forensic anthropology and forensic archaeology are key components to human rights investigations as defined by the United Nations and the International Committee of the Red Cross.

a legal term referring to a deceased person

the insider’s (how members of the culture) view and understanding of that culture’s practices

the perspective of the outsider (how people who are not members of that culture) view and understand that culture’s practices