9 Identities and Power: Sex, Gender, and Race

Taylor Livingston

Learning Objectives

After reading the chapter, students will be able to:

- Describe the difference between sex and gender.

- Understand how in Euro-American cultures sex and gender are connected.

- Identify how other cultures do not conflate sex and gender.

- Summarize how other cultures understand sexuality.

- Explain why a biological basis for human race categories does not exist.

- Discuss what anthropologists mean when they say that race is a socially constructed concept and explain how race has been socially constructed in the United States.

- Describe how ethnicity is different from race, how ethnic groups are different from racial groups, and what is meant by symbolic ethnicity.

Sex and Gender

In the early 1990s, the actor Julia Sweeney played the character “Pat” on Saturday Night Live (SNL). Pat is an androgynous character and the skits focus on people not knowing Pat’s gender identity, or how they choose to identify themselves (male, female, neither) based on the culturally constructed category of gender. The comedy comes from how uncomfortable this makes the other person. Most of us would find these skits cringe-worthy now, but the skits, like the one below, do touch on the cultural truth that not knowing someone’s gender makes us uncomfortable because we do not know how to refer to them or describe them, as our language is gendered: Should we use he/him/his or she/her/hers or perhaps they/them/theirs? In the skit below, the pharmacy worker, played by Catherine O’Hara, does not know what to sell Pat–the pink Daisy razors or the Gillette? What type of lotion? What kind of deodorant? –as event the items we buy for person hygiene are gendered. They are marketed and sold to men and women differently based on what companies’ think consumers of different genders prefer. These items even are priced differently, as often female-gendered items are subject to the pink tax, which charges more for the same or similar goods marketed to women than to men. A report from California in 1996 found that on average, women paid $1,351 more per year because of the pink tax (Civil Rights. Gender Discrimination. California Prohibits Gender-Based Pricing. Cal. Civ. Code § 51.6 (West Supp. 1996)). In 2021, that is almost $2,265! The pink tax also reveals another reason not knowing someone’s gender makes us uncomfortable–because in our society, we treat men and women differently.

The division of humans into two sexes that correspond to two genders seems natural, but it is socially constructed. Socially constructed means that society created a concept. It seems natural, but that is only because it is reinforced through social institutions (roles in families, jobs, laws, medicine, education). For example, in our culture the sex assigned to infants at birth is assumed to be permanent and that physically male child will display male gender characteristics and a physically female child will display female gender characteristics. However cross-cultural comparison shows us that sex and gender are not always viewed as identical and limited to a system of male/female opposites. In cultures with only two sex and gender systems and these are seen as identical, individuals who do not conform to this model are seen as deviant and abnormal; the behavior is seen as “sinful” or taboo, because what is not understood or is unfamiliar is seen as a threat. Having other gender categories are ways other cultures take individuals who do not fit the traditional gender binary of male/female and recognize and incorporate them without stigmatizing these individuals as different.

What is Sex?

For over two thousand years female and male bodies were not conceptualized in terms of difference. For example, medical texts from ancient Greece until the late eighteenth century defined male and female bodies as similar with the only difference is that female bodies have genitalia on the inside. It is not until the late 18th century that we get the concept of sex as we think about it currently–biological differences in males and females–with a focus on difference instead of similarity. This can be seen in where men and women go for reproductive healthcare. Women go to an obstetrician/gynecologist because their bodies are perceived to be vastly different than men’s. But where do men go? Men receive reproductive healthcare at a general practitioners’ offices. There is no special healthcare provider for their reproductive needs because men’s bodies are considered the “normative” in our culture. The easiest example to see this, if you have a female body, is the temperature of most public places. Many people who have female bodies would consider the temperature to be too cold, while men find it comfortable. Public buildings are often set a temperature thought to be comfortable for men’s bodies. Females who have large fat deposits near the core of their body (breasts) are better able to regulate their body heat than men. Further, women’s clothing is often thinner and shorter than men’s–think about an office building wear a man is required to wear a suit and a woman wears dresses (Chilly at Work? from the New York Times).

Problems with the concept of sex

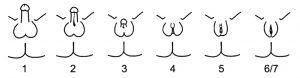

In the US and many Western countries, we assume that sex is dichotomous and discreet as it refers to to biological differences between men and women. We assume that those who are women have two XX chromosomes, have a uterus, ovaries, and vagina, and more estrogen in their bodies. Conversely, men have XY chromosomes, have penises and testicles, and more androgens (like testosterone) in their bodies than women. But, biology is actually a lot messier than this conception. Biological sex is actually a spectrum with our ideas of male and female bodies lying at two different ends. Below is an image call the “Quigley Scale” developed by pediatric endocrinologist Charmian Quigley in 1995 to show the range of normal infant genitalia from “fully masculinized (1) to “fully feminized” (6/7).

Variations in genitalia can result for numerous reasons including chromosomal variations such as Turner Syndrome (XO) and Klinefelter syndrome (XXY), hormonal variations such as congenital adrenal hyperplasia or androgen insensitivity syndrome. People who are born with a person is born with a reproductive or sexual anatomy that doesn’t seem to fit the typical definitions of female or male are referred to as intersex. Again, these are normal biological variations for bodies and are not incredibly rare. Biologist Anne Fausto-Sterling estimates that 1.7% of the world’s population are intersex. That is more common than red hair (Sterling 2000). As intersexed bodies do not fit our concept of male and female bodies, intersex infants are often assigned male or female sex at birth with surgery performed to alter their bodies to fit society’s understandings of bodies that are male and female. Usually, multiple surgeries are performed and those who are intersex are made to feel ashamed of their bodies (https://interactadvocates.org/faq/). This is not the case around the world, were some society’s “make room” in their culture for bodies that do not fit the concept of sex (see “Other Cultures, Other Ways” below).

Gender identity, presumably emerges from all of those corporeal aspects via some poorly understood interaction with environment and experience. What has become increasingly clear is that one can find levels of masculinity and femininity in almost every possible permutation. While biology implies some basic physiological facts, culture gives meaning to these in such a way that we questions whether biology can exist except within the society that gives it meaning in the first place. This implies that sex, in terms of raw male or female, is already gendered by the culture. In this model, sex is not something that one has or a description of what someone is. Without the concept of gender we could not read bodies as differently sexed. It is gender that provides the categories of meaning for us to interpret how a body appears to us as “sexed.” In other words, gender creates sex.

Think about the video of Pat above. Why are people so uncomfortable around Pat? Because they do not know Pat’s gender. They cannot “read” Pat’s body, so they do not know their sex. Similarly, think about what people say to parents of infants. I don’t know what genitalia the infant has under their diaper, but if they are wearing pink, I may say, “Oh, what a little princess!” Or if they were wearing a onesie with a baseball on it, I may say, “Oh, he is going to be so strong.” The infant’s sex only matters because have a gender category for it. I know how I am supposed to refer to the child and whether I assign it feminine or masculine characteristics.

What is gender?

Intersexed peoples’ bodies are seen as problematic and needing to be changed because they do not fit into Western culture’s sex/gender binary, or a concept or belief that there are only two genders and that one’s sex or gender assigned at birth will align with traditional social constructs of masculine and feminine identity, expression, and sexuality. The sex/gender binary assumes that masculinity and femininity, are something that we’re all born with and it’s natural. The expectation is that someone who has a uterus displays feminine characteristics for someone who has a penis to display masculine characteristics. These characteristics are opposite each other and cannot overlap. But, they are valued differently what is masculine is often given more power or like that more highly regarded than what is considered feminine (think back to the different doctors for reproductive health or the fact that jobs where those who identify as women outnumber those who identify as men are less highly paid). Finally, the assumption is that those those who are female will be attracted to those who are male, this is called heteronormativity.

In reality, gender, or the patterned and repeated acts of behaviors that society and culture determine are to be displayed by men, women, and sometimes other identity categories, is more of a sort of continuum with some people displaying more feminine characteristics some display more masculine, but most of us are sort of somewhere in the middle. These patterned and repeated acts can be things like what type of clothes you wear, how you wear your hair, if is is socially acceptable for you to wear makeup, how we hold our body, or how we speak. As we discussed in the “Language and Culture” chapter, those who identify as women are thought to be more likely to use “uptalk” or ending a sentence with a qu

estion and have a vocal frye. For gender differences in how we hold our bodies, think about how men and women sit. Women are taught to take up as little space as possible, and thus, often sit with their legs close together or crossed. Men, are more likely to sit with their legs far apart. You may know this as “manspreading.”

But not all people feel particularly masculine or feminine. Further, many people do not identify with the sex they were assigned at birth (cisgender). How do cultures account for people in these categories? In Western society, it has become more common to refer to people who do not identify with the sex they were assigned at birth as transgender. For those who feel neither particularly masculine or feminine, they are non-binary. The terms transgender and non-binary do not imply any specific form of sexual orientation (trans and non-binary people may identify as queer, heterosexual, homosexual, bisexual, pansexual or asexual.)All people do not fit into the categories of male and female because it is socially constructed–we made it up. To see this, think about how until the 1900s pink was actually a masculine color blue was for girls. Or all the changes society has gone through as what it means to be a man and a woman have changed in our society since the 1950s. In the 1950s, it far more common for women, especially white, middle class women, to stay at home and the be the primary caregiver and not work outside the home. That is no longer the case. Most women work outside the home and it is more common for men to be equally involved as caregivers for children.

But because our society conceives of the sex/gender binary as being natural, those who are transgender or gender non-conforming as seen as exceptions. In other cultures, there are more categories for people whose bodies do not fix the Western conceptualization of male and female bodies and for those who do not identify with the sex they were assigned at birth.

Other Cultures, Other Ways

While in American and European Culture this is new information, as we often conflate sex and gender, and as such have only two accepted genders—male and female. However, this is not the case in all cultures. The terms third gender and third sex describe individuals who are considered to be neither women nor men, as well as the social category present in those societies who recognize three or more genders.

The state of being neither male nor female may be understood in relation to the individual’s sex, gender role, gender identity or sexual orientation. To different cultures or individuals, a third sex or gender may represent an intermediate state between men and women, a state of being both (such as “the spirit of a man in the body of a woman”), the state of being neither (neuter), the ability to cross or swap genders, or another category altogether independent of male and female. This last definition is favored by those who argue for a strict interpretation of the “third gender” concept.

Two-spirit

The third gender category of two spirit is found in over 150 Native American cultures. In terms of bodies, the most common two spirits would be assigned as having a male body at birth, but some would assigned as physical females or intersex. In most Native American cultures, two spirit people do some women’s work and mix together roles, dress, and behavior of both men and women. Since not male or female; seen as mediators between men and women. This idea is often connected to the group’s cosmology. For example, among the

Navajo, the creator, Changing Woman, has both male and female aspects. Two spirit people are an example of where variation in bodies or gender identity is sanctified and not viewed as a threat or an exception.

Hijras

Hijras of India are also a gender role that is considered neither male nor female. Hijras are most commonly assigned physically male at birth, though some intersexed individuals identify as hirjas. Hirjas dress and live as women, often overly emphasized (caricature) of women’s behavior, and allowed to do certain things like curse and smoke that Indian women are not. If assigned physically male at birth, hirjas undergo an operation to have their genitals removed. Hirjas are followers of Hindu goddess Bahuchara Mata, goddess of procreation, and earn their living through life ceremonies such as births and marriages where they ask the goddess to bless the baby or married couple with prosperity and fertility. In recent years, hirjas have won election to public office in India and in 2010, were granted their own identity category on voter’s rolls.

Lived Reality of Sex and Gender

Though sex and gender are socially constructed they do have real effects on people’s lives. If we look around the world there are worldwide gender in equities: two thirds of the people who are not literate are women; seventy percent of the world’s poor women; women represent a growing number of people who are diagnosed as HIV positive or who are living with AIDS; only 16 countries the women represent at least 25% of the population in legislative bodies; one in four or one into women have been subject to some form of physical or sexual abuse in our lifetime; transgender and non-binary people count for the most murdered group of people in the world (United Nations Gender Facts).

We can also see this if we look closer to home. The US has a gender-wage gap. On average, white, women earn 79 cents for every dollar a white man makes this is even less for Black women, Hispanic and Latino, and American Indian and Alaska Native women. The gap is largely do to the fact that women’s work is undervalued. Further, women with kids face a motherhood penalty they’re less likely to be hired and offered lower salary and are often offered fewer promotions than men. Comparatively, fathers make 119% more than single men. Also, women are more likely to work in low paying jobs, domestic work and childcare. If the trend keeps it’s pace, based on 1988 to 2019 data, Asian women will earn equity with white men in similar jobs in 2041, non-Hispanic white women in women in 2069, Black women in 2369, and Latinx women in 2451 (https://www.aauw.org/resources/research/simple-truth/).

Further, there have also been a proliferation of state bills targeting trans youth, specifically barring them from participation in youth sports. This would mean that trans girls would not be allowed to play girls sports and trans boys will not be allowed to play boys sports. These bills have recently been passed in Mississippi and Arkansas, but are under consideration in many more states in the US.

These examples, and many more like them, show us that although sex and gender are socially constructed, they have very real effects on people’s lives.

Race

The summer of 2020 laid bare many Americans that although the Declaration of Independence states that “all men are created equal,” that is not the case for Black Americans and other Americans of color.

It is commonly accepted that race is not biologically real, so why do some people receive unjust treatment in our society? The problem lies in social construction–the bugaboo of sex and gender is also applies to assigning meaning and value to differences in skin tone.

Why do we see differences in Skin Tones?

There is 92% variation within so called races and about 8% genetic difference between so called races. What does that mean means? Well, it means if we compare the genetics of two white people compared to one Black person, there is likely to be more genetic difference between the two white people than between the white people and the Black person (American Anthropological Association Statement on Race)

Race is a very old socially constructed category that unfortunately has been used to rank and classify people into hierarchies with the white Europeans who were making these hierarchies at the very top. When we look around the world, we do see that there are human differences, but there are reasons for that difference that have to do with ancestry. The first is the idea of skin color being used as a racial category, this is something that is very Euro-American. Other countries don’t have the same race systems we do remember it’s culturally constructed it’s going to be different in every culture. There are no absolute categories of race because skin tone because is not totally based on genetics; it’s based on the environment.

As Nina Jablonski argues in the TED Talk below, skin color is really reflective of UV exposure and adaptations to protect against too much or too little IV exposure in populations. Skin tones have evolved independently in different places. So, by looking at someone skin color we can’t say if they are related closer ancestry or not, only that their ancestral populations had similar levels of UV exposure. Darker skin has more melanin in it; melanin is like a natural sunscreen. In places with more UV exposure (closer to the equator), darker skin would be selected for because of that sort of natural sunscreen means you’re less likely to get skin cancer from UV radiation exposure. But it’s also something that would not be selected for outside of these high UV environments, because it makes you more prone to things like rickets, or a malformation of the bones, because because you get vitamin D through sun exposure. Vitamin D is needed for calcium absorption (so you can grow healthy bones). Similarly, in environments with less UV radiation, lighter skin, would be selected for because you are better able to absorb vitamin D. This would prevent you from getting rickets. But, if you have lighter skin in high UV environments, you are more prone to skin cancer. UV exposure also depletes folate (B vitamins), which is problematic for those with light skin in high UV areas as it helps with fetal neural tube formation. Having lighter skin in a high UV environment would not be selected for because you are at greater risk of having children with neural tube problems, the one of the most common is spinal bifida, which is opening the back where the spinal nerve is exposed. These children may life-long complications, and until recently, depending on severity of the case, would die at early ages.

So why, if race is not biological, why do we see differences in the way that people look around the world? Much of these difference have to do with clinal variation, continuous and gradual across geography, and not discrete. Think about everyone you would categorize as white. Do they have the same color skin tone? No, there is a variation and it is linked to the UV exposure of their ancestors. Most human variation is clinal. Think about hair texture. Hair has many different textures and a person doesn’t just have straight or curly hair. Hair can be thick, thin, wavy, coiled, etc. But, remember, there is more variation within so called races than between them. And thus, there is no specific genetic traits that are exclusive to “racial” groups. You can have light skin and tightly coiled hair or darker skin and straight hair. An example to disprove the idea of racial categories as genetic is a eye shape called the epicanthic eye fold. Although thought to be associated with those of East Asian ancestry, epicanthic eye folds can be found among some American Indian groups, the San in Botswana, and some Indigenous Scandinavian groups like the Sami.

If Race is Socially Constructed, Where Did it Come From?

Humans understand their world by creating categories. This works for words (think nouns, adjectives, verbs, and adverbs), but not so well for people because we are far more alike than we are different. This did not stop humanity from trying. This is detailed by a famous evolutionary biologist, Stephan Jay Gould, in his book, The Mismeasure of Man. Gould argues that the history of racial categories can be traced to white Europeans (not actual scientists) measuring craniums or skulls of people from different ethnic world groups. These measurements were used to create hierarchies of racial categories with white, Europeans at the top. These measurements were flawed and reflected the biases (read: racism) of those “scientists” making the measurements. Unfortunately, these falsified racist measurements and resulting hierarchies were used as a means to justify differences in economic status, justify racism, colonialism, classism, and sex. Which white European group was at the top of the hierarchy varied depending on the country the “scientist” was from– if from France, then the French were the smartest and had the most ideal skulls with the best measurements. From the UK? Well, then, “roll, Britaina,” British people were at the top of the hierarchy. What this amounts to is biological determinism, the belief a person’s biology explains why they do what they do or why they are the way they are. This suggests that shared behaviors, cultural differences, class, are the result of biological traits, and not cultural differences. Moreover, these supposed biological differences distilled as “races” were arranged into a social hierarchy.

What happened was that overwhelmingly white European male scientists took their preconceived notions about race, sex, class, and intelligence, and performed “studies” (they were not actual scientific research) that served to reinforce their a priori beliefs. This included making sure that your measurements of skulls ensured that their group of people came out as being the most perfect. This approach was widely accepted because it had the air of authority from being called “science” and involving quantification–numbers, measurements of skulls. There are some reasons it was appealing to people in the past. It took the abstract categories of races and ideas of thinking that certain groups were better than others and treated it as if it were real. It also was appealing because it provided a hierarchy and reduced complex phenomenon (clinal variation) to simple-to-understand “facts.”

In America, these “studies” were used to justify the enslavement of people of African descent and the disposition of land from American Indians. These “studies” and the ideologies about racial categories they created were also used to uphold laws about who counted as an American. For example, in 1914 Takao Ozawa, a Japanese American businessman who had been living in the US for over twenty years applied for citizenship. He was denied, even though he appealed all the way to the Supreme Court, because he was not white, even though the law he was applying for citizenship under established in 1906 made no mention of whiteness being a required qualification.

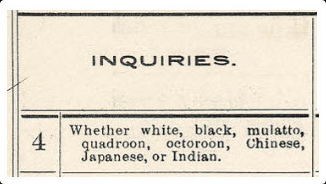

Ideas about racial categories also ebb and flow depending on the cultural ideas. These can be seen in Census records. The 1890 Census only had the categories of “white,” “Black/Mulatto/Quadroon/Octoroon” (the last three are racial slurs referring to someone who had Black and white ancestry and the amount of Black ancestry that person had), “Indian” ( meaning Native American) and “Chinese/Japanese.” Note that these categories would be assessed by a Census taker. You were unable to select your own race until 1960. These categories reflect concern about how much Black ancestry a person had following the end of reconstruction and also reflect the growing number of Japanese immigrants to the country to supply labor for the railroad. Ten years before, Japanese was not on the Census. Compare this to the 2010 Census where for the first time since it’s introduction in 1930, Hispanic origin was not a race, but considered an ethnicity, and there are six racial categories: “white,” “American Indian or Alaskan Native,” “Asian Indian, Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Filipino, Vietnamese, or Other Asian,” “Black, African American, or Negro,” Native Hawaiian, Guamanian or Chamorro, Samoan, or Other Pacific Islander,” and “Some Other Race” (Measuring Race and Ethnicity Across the Decades).

All of this is to say that racial categories vary over time because there is no biological basis for race. The ebbs and flows of racial categories largely reflect the historical time periods and the culture, just as the creations of these racial categories did.

Do Other Countries Have Similar Racial Categories?

While the US system of race is based primarily on skin color and assumptions about geographical ancestry, this is not the case around the world. For example, racial categories in Brazil are quite different. Although both the US and Brazil have a legacy of colonialism and slavery, Brazil was the last country in the Americas to abolish slavery. In Brazil, race is also based on skin tone, but it is a continuum between “white” and “black.” There are several different categories of race or tipos as it is known in Brazil, most of which do not have a comparable category in the US (Color, Genomics, and Racial Ancestry in Brazil). There are so many categories, that anthropologists have identified more than 120! While Brazil’s Institute of Geography and Statistics established five official racial categories in 1940 to facilitate collection of demographic information that are still in use today: branco (white), prêto (black), pardo (brown), amarelo (yellow), and indígena (indigenous), many Brazilians reject these categories and prefer the continuous categories of the tipos (PBS: Brazil a Racial Paradise?)

If it Socially Constructed, Why Does It Matter?

If race is socially constructed and varies around the world, why does it matter? It matters because people in this country and around the world are treated differently because of their perceived race. The effects of the categories created and hierarchies created many years ago continue to shape people’s lives.

These effect everything from the wealth gap, to birth outcomes, where Black women are over twice as likely to die in childbirth than white women (Burris and Parker, 2021).

RACE – THE POWER OF AN ILLUSION: How the Racial Wealth Gap Was Created from California Newsreel on Vimeo.

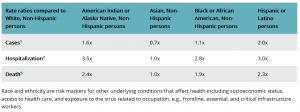

But these effects extend beyond the categories of Black and white, as the novel coronovirus pandemic has revealed. Minority populations are more likely to die from COVID-19 that whites,

and 2020 and 2021 has seen a rise in attacks against Asian American and Pacific Islanders because of racist language used to describe the origins of the virus. So, while race may not be “real,” it shapes how you live and how you die.

Key Takeaways

- Understandings of sex and gender are shaped by social norms and beliefs, and are upheld by institutions.

- Views on sex and gender have changed from considering them the same to recognizing that sex refers to biological characteristics while gender points to a person’s social identity.

- Anthropologists have helped challenge rigid perspectives on gender and sex binaries.

- Because sex and gender are social constructions that have changed over time, they can be transformed to create equitable societies.

- Race is not biological. Differences that we see in people are based on clinal variation.

- Though not real, race has real effects on people’s lives.