7 Language and Communication

Taylor Livingston

Learning Objectives

By the end of this lesson, the student will:

- Know about communication systems in animals as well as differences in human communication.

- Understand the evolution of the capacity for language in humans.

- Describe the structural elements of language (phonetics, morphology, syntax, semantics)

- Know how language influences perception and cognition.

- Understand the concept of linguistic relativity and the Boas-Jakobsen principle.

- Recognize the influence of region, class, gender, and ethnicity on language.

Across the world, there are approximately 6,000-7,000 languages. An impressive number when you consider there are only 143 countries. All humans have language or the capacity for language—along with culture, it’s what makes us different from all other animals. The two concepts of language and culture are intwined in that we could not have culture without language and culture is passed down to the next generation through language. Language is so important to humans that our ears best hear the frequency of the human voice. So, what is this aspect of humanity that makes us human?

What is language?

Language: arbitrary symbolic communication systems composed of both verbal and non-verbal speech used to encode one’s experience of the world that is shared with others.

All language is symbolic. A symbol is something that refers to something else. For example, the word “tree” is a symbol that refers to the large plants with bark that grow from the ground with branches and leaves. We use symbols to communicate our ideas and observations. These symbols are arbitrary, meaning there is no obvious relationship between the symbol and what it represents. Using our tree example, there’s really no reason why the word “tree” represents a plant that grows from the ground that has branches and leaves and a large trunk. The word “tree” does not resemble the object to which it refers, thus there is no reason why the letters T R E E communicate the concept of a large plant with a trunk.

Languages are composed of verbal and verbal speech. This means they are composed of words like “tree,” but also other forms of communication like body movements, emojis, and hand gestures, like those in American Sign Language used by American Deaf cultural communities. We say that language encodes our experience of the world because language is how we think. It’s how we express ourselves and how we organize the world. When I see a large plant with branches, leaves, and a trunk, even if I have never seen that particular type of large plant before, my brain recognizes that as a “tree.”

Origins and Acquisition of Human Language

Where did language come from? Estimates are that we acquired the ability to speak from about 200,000 to 50,000 years ago. The most recent research has put forth a hypothesis that we use language as a means to pass down information about how to make tools and that sort of hijacked our brain to specialize in processing information connected to language. Making tools was such an important aspect of our culture and survival that we needed to be able to pass down how to make those tools to our children and to other people (James, 2018).

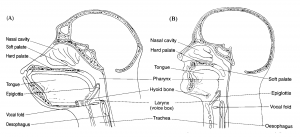

It is generally agreed upon that there were two steps in the evolution of human language. It’s thought that our ancestors began to produce new calls by blending old calls. The second change would require changes in the brain to produce these discrete forms of speech by controlling the ability to produce sounds. In addition to these two steps, the capacity for language also required changes in biology to be physically able to speak and having the auditory connections to process spoken language. Humans’ larynx (voice box) is lower in the throat than other animals. Additionally, humans have a rounder tongue and soft palate; these changes would have allowed human ancestors to make more sounds than apes. Further, specialized regions in the brain, including Broca’s area in the left frontal lobe (near your left temple) that controls turning ideas into speech, and Wernicke’s area, in the left temporal lobe (behind your left ear), which controls auditory processing (understanding speech), enabled language. These specialized regions were crucial to language development as producing, processing, storing, and interpreting language requires a great deal of brain power (Light, 2018; Rauschecker, 2019).

It is generally agreed upon that there were two steps in the evolution of human language. It’s thought that our ancestors began to produce new calls by blending old calls. The second change would require changes in the brain to produce these discrete forms of speech by controlling the ability to produce sounds. In addition to these two steps, the capacity for language also required changes in biology to be physically able to speak and having the auditory connections to process spoken language. Humans’ larynx (voice box) is lower in the throat than other animals. Additionally, humans have a rounder tongue and soft palate; these changes would have allowed human ancestors to make more sounds than apes. Further, specialized regions in the brain, including Broca’s area in the left frontal lobe (near your left temple) that controls turning ideas into speech, and Wernicke’s area, in the left temporal lobe (behind your left ear), which controls auditory processing (understanding speech), enabled language. These specialized regions were crucial to language development as producing, processing, storing, and interpreting language requires a great deal of brain power (Light, 2018; Rauschecker, 2019).

Aspects of Language

Since language is so important to humans, linguists, those who study language, have long been interested in finding out what aspects of human language distinguish it from the communication systems of other animals. Linguist Charles Hockett (1960) created a hierarchical list of characteristics, or design features, listing what aspects are found among all animal communication systems, as well as those unique to humans (the 14 below).

The three design features below are found in all animal communication systems:

- Vocal-Auditory Communication—Sounds are produced that can be heard. For example, the songs of birds.

- Semanticity—Produced sounds have meaning. Birds’ signing could mean “this is my area” or “I am looking for a mate.”

- Pragmatic function—The communication system has a function, which may help the species survive by influencing a behavior.

Found in human and some animal communication systems:

- Interchangeability—Members of the species can send and receive messages. This is not found in all communication systems, as in some species of bird, only males can sing.

- Cultural transmission—The communication system must be learned. It is not innate. Using our bird example, male birds have the biological capacity for language, but have to learn the songs.

- Arbitrariness—There is no obvious relationship between the communication and to what it refers. Back to birds: the songs male birds sing have no logical relationship. If you are not a member of that species of bird, you have no idea what the song means.

Design Features Unique to Human Language:

As language is a marker of how we’re different from other animals, there are certain parts of human language that are very different from other types of communication systems. No other communication system is as complex as human communication. It’s related to her capacity for symbolic thinking. It allows us to talk about things that aren’t there in front of us to make plans, to coordinate, to cooperate with other people. As such, there are certain design features that set us apart from other animal communication systems. They are:

- Discreteness—There are complex signals that can be broken down into distinct repeatable and re-combinable units. For examples the word “spots” can be changed into “tops” and the world “pots” by using the meaningful units of letters.

- Duality of Patterning—Distinct units of sounds can be combined to form meaningful units (words). Meaningful units can also be combined to form new meaningful units. The words “breakfast” and “lunch” can be combined to make the new word “brunch.”

- Displacement—The ability to communicate about things in remote time and space. As humans, we don’t have to be talking about something that is in front of us. We could be talking about something that happened to the past or is going to happen in the future. We can also talk about objects or events in the next room.

- Productivity—The ability to express an infinite number of messages, most of which have never been expressed before about an unlimited variety of subjects. Humans have the ability to make new words—think about the word created in December 2019, COVID-19.

- Recursiveness—Complex signals can be incorporated as parts of more complex signals. For example, if I said, “he said that she said that they thought that she said that she liked him.” You understand what I mean, even though it is a complicated sentence.

- Prevarication—The ability to be dishonest. Humans do not have speak the truth. We can lie.

- Reflexiveness—The messages we communicate can be about other messages or even about the communication system itself. I am typing sentences communicating to you aspects of our communication system—very meta.

- Learnability—The ability to learn a language is innate and we can learn more than one language.

Language Acquisition

All humans have the capacity to learn language. Babies learn language without having to be taught nouns, adjectives, and verb tenses. This led linguist Noam Chomsky to propose the concept of Universal Grammar, which argues the basic template for all language is embedded in our genes. This theory is controversial, but it is true that there are a set of principles, conditions, and rules that underline all languages.

There appears to be a limit to this hard-wiring, as anecdotal evidence suggests it unless a language is learned before about twelves years of age, one cannot become fluent in it. This idea is called the Critical Age Range Hypothesis. Support for this hypothesis comes from stories about abused or neglected children who were never able to learn language. For example, the story of Genie.

There appears to be a limit to this hard-wiring, as anecdotal evidence suggests it unless a language is learned before about twelves years of age, one cannot become fluent in it. This idea is called the Critical Age Range Hypothesis. Support for this hypothesis comes from stories about abused or neglected children who were never able to learn language. For example, the story of Genie.

Genie was rescued from abusive parents at age 12 in the 1970s from California. She was trapped in an attic until this age strapped to a chair and had little interaction with others. Even after she was recused, working extensively with a linguist, she was never able to move beyond the speech capabilities of a toddler (simple syntax with a disregard for the rules of grammar). Other examples include the “Wild Boy of Avignon,” who was found in the French woods at the age of eight. He did not speak any language and although he was instructed in French, no matter how much time and effort were put into his education, he never developed the ability to be fluent in French.

The Building Blocks of Education

Supporting Chomsky’s notion of universal grammar are the underlying universals of language structure: Phonemes, morphemes, and syntax.

Phonemes are significant, but not meaningful sounds. They are the smallest discrete unit of sound in a language. Constants and vowels would be phonemes. For example, the sounds the letter C, T, or S make are phonemes.

Morphemes are meaning bearing units. Morphemes can be words, like “cat” or can be smaller than words, like “s.” In English, “s” indicates plurality. For this reason, the word “cats” has two morphemes, “cat” and “s.”

Syntax is grammar. It’s the rules that govern how morphemes or words are combined to make meaning. In English, the order of words in a sentence matter. For example, the sentence “The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog.” Does not mean the same thing if I switched “the lazy dog” with “the quick brown fox.” (The lazy dog jumps over the quick brown fox.) Now, the fox is being jumped over.

Language and Anthropology

The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis

Edward Sapir was one of Franz Boas’ students who became the father of American linguistic anthropology. Sapir earned this title because of his documentary efforts recording and studying the language and cultures of Native American groups, which were rapidly disappearing due to American assimilationist policies. But Sapir’s most famous contribution to the field of anthropology was a hypothesis developed with his graduate student Benjamin Whorf.

In addition to his graduate studies, Whorf worked for an insurance company investigating fires. He noticed that companies placed warning signs around full barrels of gasoline, but did not do so around empty barrels. Similarly, employees were very careful around full barrels, not discarding cigarette butts near them, but the same could not be said for empty barrels. When reviewing one fire that was started by someone discarding a cigarette butt near an empty barrel of gasoline, Whorf theorized that the employees believed “empty” meant nothing was in the barrels. Unfortunately, empty barrels of gasoline are full of volatile gases, which are much more flammable than gasoline. This incidence and their research with similar findings led Whorf and Sapir to theorize than language shapes thought. Their hypothesis, also called linguistic relativity, argues that the structure and words of a language influence how its speakers think and behave.

Our ideas about the extent that language shapes thought has shifted a bit, and are more closely aligned with Guy Deutscher’s Boas-Jakobson principle. This principle argues that language does influence a speaker’s mind, but not to the extent that it controls how we think, but influences what we habitually think about. For example, a speaker of Tzeltal, a Mayan language, always knows which direction (North, South, East, West) they are facing, as their language requires that they know the direction they are facing (Wesch, 2016). A Tzeltal speaker cannot say “I am going to town.” Instead, they say, “I am going northwest to town.” In this way, language doesn’t control their thought, but it does shape it by having Tzeltal speakers think habitually about direction—much more so than native English speakers.

Language and Culture

Language and communication are embedded in cultural power systems. For example, in American English, those who use the phrase “I ain’t” instead of “I am not” are judged for not speaking “properly” and using standard American English. In many languages, how people speak can be a marker of which social group they belong to or how they identify, as speech is influenced by gender, age, class, and ethnicity. Those who use the phrase “I ain’t” are generally thought of as being less educated, belonging to a lower social class than those who say “I am not.” However, no one speaks the same way all the time in every social setting. When I am in the South for long periods of time, my speech changes, and my accent becomes more pronounced. Similarly, you probably do not speak to your grandparents the same way you speak to your peers. This is called code-switching. The study of these different ways of speaking and connections to power relations and social groups is called sociolinguistics.

Although society may stigmatize some forms of speech, (think about the overuse of “like” by teenage girls influenced by the way girls in the Valley of California began speaking in the 1980s), there’s not a scientific sense in which one grammatical pattern or an accent is better or worse than another. Communication is about relaying messages. If the message can be understood, then it is an effective form of communication. If you say, “I ain’t going to read this chapter;” I know what you are trying to convey.

The same is true for dialects, or a variety of speech or language variation. Languages are spectrums. All forms of language, all dialects, are equally functional and equally valid forms of communication. This isn’t a political statement, but it has political implications because of the power systems embedded in language. Consider the way some New Yorkers’ speak, not pronouncing the “r” in words (“fourth floor” sounds like “fawth floah”). This way of speaking is found primarily among working-class New Yorkers and would not be considered Standard American English (think about how newscasters speak) (Labov, 1972). But, the same practice of not pronouncing the “r” is considered posh and the standard in the United Kingdom. Called “Received Pronunciation,” this is the way the Royal Family and British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) newscasters speak. (Light, 2018). As famed linguist Uriel Weinreich states, “A language is a dialect with an army and a navy.”

Where did dialects come from?

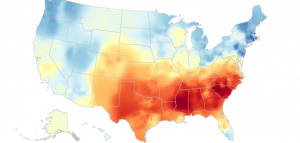

The United States has a great number of dialects. Many of them are based on geographic region of the country. Linguists can even tell with a reasonable degree of certainty where you are from based on your answers to questions like, “How would you address a group of people?” A linguist named Bert Vaux designed the Harvard Dialect Survey in the 1990s do just this. It went online in 2002 revised with the help of Scott Golder, and was published by the New York Times in 2013 (links to external site).

These regional differences in America are a result of the immigrants who settled into these areas and the migration routes of other settlers as they moved west to settle in new areas. Dialects were also influenced by speakers of other languages as settlers moved into new areas. Ways of speaking and words were borrowed from contact with speakers of Spanish, French, Native American languages, as well as enslaved peoples of African descent who spoke their native languages. Geographic boundaries (islands, mountains) would have kept some of these ways of speaking linguistically isolated from others (Light, 2018) (see the video below about the accent of Tangier Island, VA).

In addition to geographic location, how we speak is often related to our age, as well as gender and ethnicity. For example, females are more likely to use “high rise terminal” or uptalk, which turns a declarative sentence into a question. (Say these two sentences aloud to hear an example: “The sky is blue.” “The sky is blue?”) Females are also thought to use vocal fry more. Vocal fry or the creaky voice (see click below) is the dropping of the pitch at the end of a word or phrase. It’s primarily associated with the Kardashians, but traces its roots to the 2000s with the way Paris Hilton speaks. Uptalk and vocal fry are thought to be “obnoxious” or “unprofessional” by most people. National Public Radio’s “This American Life” received a number of complaints about female reports using vocal fry, but no one complained about the host’s Ira Glass, vocal fry. In fact, all genders use uptalk and vocal fry, though it is most associated with young women. Others think vocal fry and uptalk critique are attacks on young women and it is discriminatory. Linguists have found that vocal fry and uptalk signal submissiveness or being non-threatening in social situations. Studies have found that while some see these vocal patterns as unprofessional, many young women perceive it as belonging to an upwardly mobile and well-educated group of women.

Our ethnicity may also shape how we speak. The often racist parodied and denigrated African American Vernacular English (AAVE) is an example. AAVE is thought to have originated among polyglot enslaved Africans exposed to the English of the upper classes and poor whites, as it includes features of West African languages, Standard English, and non-standard English dialects of the 17th century British Isles. Though viewed as not standard English, AAVE is a complex and functional language. It has its own grammatical rules, vocabulary, and pronunciations. It as just as much a vernacular as standard English, Scottish English, or a Southern accent. Indeed, despite popular belief to the contrary, there is no such thing linguistically as “bad grammar.” All languages and dialects of languages function equally well for their native speakers: they allow us to communicate fluently. Even if a way of speaking is considered less sophisticated by social conventions, scientifically speaking there is no distinction between dialects and languages in terms of “correctness.”

Abstracting to other languages, there are similarly no more complicated or less complicated languages. All languages are equally complex and rule-governed. As long as native speakers can communicate messages, it is a valid language.

Language Change

As mentioned above when discussing dialects, when languages meet, they change. A example of such a situation can be found with pidgins. Pidgins are not full languages, but communication systems with the bare minimum ability to communicate, usually for a specific context like trade or colonialism. They are not spoken by anyone as a first language and are not learned by children. They’re only learned by adults for a specific application, and for this reason, have risen and many colonial situations. For example, an English based pigeon in Canton and Guangdong China emerged when there was a large European presence in the region, but neither group needed or wanted to properly learn the other’s language. So, speakers of the languages made do with creating a pidgin that started in the 18th century. It had mostly English words with some Chinese grammar and a few words of Portuguese. The phrase, “sen one piece cooly come my sop look see” in the pidgin would translate to “send a servant to come to my shop and see.”

A pidgin can become a full language. The result is called a creole. Creoles are learned by children and there are full rules of grammar. There are a number of creoles spoken in the US including Gullah, which is spoken mostly off the coast of the Carolinas created from the pidgin spoken by enslaved West Africans and white plantation owners, and a Creole spoken in Hawaii, which is confusingly referred to as a pigeon. There is also a family of Caribbean English-based Creoles including Jamaican Patois, which is related to Gullah and developed for similar reasons. As such, it contains words from Scottish and other non-standard dialects of English that were picked up by enslaved people from the indentured servants who they worked alongside.

Language Extinction

Another aspect of language change is language extinction. There are currently 6,000 to 7,000 languages in existence today, but in the next 100 years, over 80% of these could become extinct. Languages die because of contact with a larger, more powerful groups. For example, the indigenous residents of the British Isles spoke a Celtic language. Aspects of this language were incorporated into the Latin spoken in the area after the Roman invasion, which was then incorporated into the Germanic languages spoken by German invaders, with a bit of sprinkling of Viking language from their invasion. Together these became Old English.

If languages do not evolve into other languages, they become dead ends. This limits the diversity of the world because we know language, culture, and thought are intricately connected. Groups speaking languages facing extinction have sought revitalization efforts, such as teaching their language to the next generation. A project to protect the Omaha and Ponca languages was undertaken in 2006 to teach the language to college students and the larger community. You can explore the site here (links to external site).

With current language extinction threats, anthropology comes full circle from Sapir’s efforts among Native American groups to projects today seeking to preserve the rich diversity of one of the aspects that makes us uniquely human.

Key Takeaways

- There are 14 design features to animal and human communication systems. Three are found in all animal communication systems, and eight are unique to human language.

- The capacity for human language involved evolutionary changes in the voice box location, the rounding of the tongue and soft palate, as well as two specialized regions for vocal control and language processing in the brain.

- All languages have phonemes units of sound, morphemes, meaningful units, and syntax, rules for languages.

- Language influences how we see the world. This has change from the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis, which argues language controls thought, to the current accepted idea of the Boas-Jakobsen principle that what our culture habitually thinks about is expressed in language.

- The way we speak is embedded in power relations and reflects social groups. Our language is influenced by our gender, class, ethnicity , and region where we learned language.

- Hockett, (1960) The Origin of Speech, Scientific American203, 88–111Reprinted in: Wang, William S-Y. (1982) Human Communication: Language and Its Psychobiological Bases, Scientific American pp. 4–1

- James, B. (2018). A Sneaky Theory of Where Language Came From. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2018/06/toolmaking-language-brain/562385/

-

Labov, W. 1972. The Social Stratification of (r) in New York City Department Stores. Sociolingusitic Patterns. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.Light, L. 2018. Language. Perspectives:An open Introduction to Cultural Anthropology, 2nd edition. https://perspectives.pressbooks.com/chapter/language/

- Rauschecker JP. (2018). Where did language come from? Precursor mechanisms in nonhuman primates. Curr Opin Behav Sci. 2018;21:195-204. doi:10.1016/j.cobeha.

- Wesch, M. 2016. The Power of Language. The Art of Being Human. https://anth101.com/language/

something that refers to something else

there is no obvious or logical relationship between the symbol and what it represents

list of characteristics of animal and human communication systems created by linguist Charles Hockett

The idea that if a child does not learn a language before puberty, they cannot become fluent in that language a

one of the building blocks of language; significant, but not meaningful sounds

a building block of language; meaning bearing units

one of the building blocks of language; the rules of language/grammar

or the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis, which argues the structure and words of a language influence how its speakers think and behave

the tempered form of the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis that argues language does influence a speaker’s mind, but not to the extent that it controls how we think

speaking in different ways in different social settings

the field of linguistic anthropology concerned with the context of language-- languages connections to power, gender, ethnicity, and class

a variation of a language

or high rise terminal; raising the pitch of your voice at the end of a declarative sentence, making it sound like a question

someone who is fluent in multiple languages

a communication system that is not full languages, but communication systems with the bare minimum ability to communicate, usually for a specific context

a full language that usually develops from a pidgin that is a mix of different languages.