12 Political Systems

Bill Belcher

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapters, students will:

- Know about different political systems (bands, tribes, chiefdoms, states; gift-based) seen for human populations around the world and through time and how these relate to population size and economic organization.

- Know about Bourdieu’s different forms of capital and how they are deployed

- Know about the appearance of judicial systems (Code of Hammurabi)

- Know about different forms of power

- Be familiar with the evolution of political systems over the course of prehistory and history

Introduction

One aspect of humanity is our political nature – in fact, some anthropologists would state that this is a defining aspect of humanity when you have more than two individuals together! Political anthropology is a field of study within anthropology encompassing an analysis of political power, leadership, and human influence in all aspects of our social, cultural, symbolic, ritual, and policy dimensions.

Models of Social Power

| Fried’s Societal Categories | Service’s Economic Categories |

| Egalitarian Societies | Band Organization |

| Ranked Societies | Tribe Organization |

| Segmented Societies | Chiefdom Organization |

| State Societies | State Organization |

Fried’s Classification of Society

Morton H. Fried’s (1967) classification is primarily based on social relationships attached to concepts of prestige and social hierarchy and the association of kin groups and non-kin groups; there is also an implied form of social evolution from egalitarian societies through state-level societies based on concepts of social stratification. Human beings tend to differentiate among each other by assigning greater or lesser prestige to them according to selected attributes. The nature of these attributes and the manner in which these attributes preserve and conveyed to later descendants that separate one form of society from another.

Egalitarian Societies

Ranked Societies

Stratified Societies

Service’s Classification of Society

Elman R. Service’s (1926) model of community organization is based on based on various cultural solutions for solving problems related to interaction by groups organized at a specific level.

Bands

Tribes

Chiefdoms

Fried and Service on States

Both evolutionary schemes have defined a state-level society, but given the different foci of these schemes, they are remarkably similar and will be group together in this discussion. States are variously defined and it may be difficult to understand for students as it is something that were living in! Some recent researchers are using terminology that represent the complexity of a state, particularly with prehistoric states (prior to the development of writing when we have no written records and have to use different sources of archaeological evidence to understand the development of the state or complex society). We could also use the term “civilization” as a short-hand for urbanized, state-level societies.

It must be emphasized that there is lots of variation among preindustrial civilizations, but characteristics of many of them include:

- Most societies are based on cities with large, complex social organizations;

- Economies are based on the centralized accumulation of capital and social status through tribute and taxation;

- There are advances towards formal record keeping, science, mathematics, and some form of writing script (in the broadest senses);

- For most of these societies, there are impressive public buildings or monumental architecture; and,

- There exists some form of all-embracing state religion in which the ruler or ruling body plays a leading role.

Thus, this is the most hierarchical form of social organization (so far!) in human culture/history. A state usually has a permanent bureaucracy and has some form of social stratification. Finally, the monopoly of power (political, economic, ideological, etc.) lies in the hands of a very few individuals.

Finally, how are we looking at concepts of a city or urbanism? A city is a large and relatively dense settlement with a population that usually numbers in at least the thousands. Cities are often characterized by specialization and interdependence with a relationship between the city itself and the surrounding hinterlands that supply labor and resources. Interdependence in the city’s population and its hinterland also includes specialist craftspeople and other groups within and outside the city. The city is usually a central place in its region and provides services for the villages in the surrounding area, but as indicated above, it is dependent on those villages for essential resources, such as food and material goods.

Cites have a degree of organizational complexity well beyond that of the surrounding village-based communities. There are centralized institutions that regulate international affairs and ensure security; often these institutions are tied into the symbolism represented by monumental architecture.

Criticisms of these Schemes

What about gift-based societies?

How do we see these societies archaeologically?

- A ceremonial center in which only a few people reside;

- A large center housing the entire chiefdom;

- A larger center housing most of the population, with the rest of it in smaller nearby settlements

Video: Where and Why Did the First Cities and States Appear?

City States

City states appeared to be a common form of rule related to the importance of large urban centers and their hinterlands. The classical definition of a city state is a self-governing entity that encompasses the boundaries of the city, but may also include villages, small hamlets, and agricultural lands surrounding it. City states were considered the most numerous in the ancient and relatively recent past, but only a few, such as Vatican City, Monaco, and Singapore, are recognized in the modern era as well as the Renaissance-era Italian city-states such as Florence, Milan, and Venice.

The most common ones that students may recognize are those of ancient Greece, including the city states of Athens and Sparta (home of The 300 and the original citizens of the Battle of Thermopylae). Deviations may be represented by large cities within a loose empire, such as Rome as a central authority and Carthage as a semi-independent city state that provided tribute to the main authority.

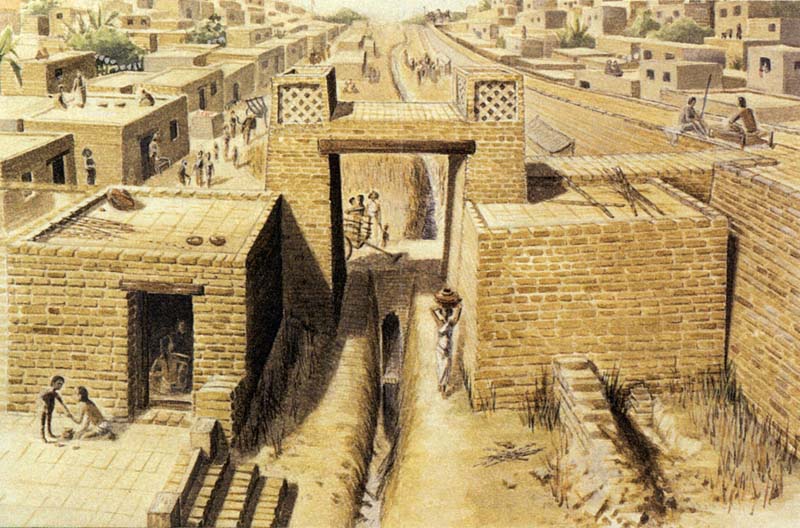

City states were represented by a group of individuals called citizens (occupants of the city) that had cultural and political allegiance to a large urban center. It appears that the city state was the most common form of governance until the recent appearance of modern empires and nation states. This was the primary form of governance that we see in prehistoric settlements with the emergence of the city in the ancient regions of the Indus Valley Civilization (northwestern South Asia), the early Mesopotamian cities (modern Iraq), and the Mayan cities (nation states of the modern Yucatan Peninsula in Mesoamerica). The latter two civilizations have writing systems that have been deciphered and the political histories of warfare and rebellion between the city states is fairly-well known.

While the Indus Valley Civilization has a writing system, it remains undeciphered. Thus, we can look at various indicators of cultural complexity and rule based on settlement pattern analysis and artifact style and distribution. It appears there are about five major urban centers (Mohenjo-daro, Harappa, Chanhu-daro, Ganeriwala, Dholavira, and Rakhigera) in the Indus Valley Civilization that encompassed over 1 million square kilometers in extent. Each large urban center seemed to have distinct versions of Indus Valley ceramic motifs and other artifacts and there seems to be a robust trade with specific resources or routes controlled by the urban centers.

Bordieu’s Forms of Capital

Pierre Bourdieu (1930-2002) developed his theory of cultural capital, with Jean-Claude Passeron, as part of an attempt to explain differences in educational achievement according to social origin. In part, this was strongly influenced by the late 1960s to 1980s influences of Marxism in the social sciences. HIs theory works on the interdigitation of three forms of capital – cultural, social, and economic. The cultural and social forms of capital are based on and not determined by the amount of economic capital possessed by social groups and individuals or agents. These three forms of capital combine, and are embodied, to produce an individuals habitus, or set of predispositions or norms, while the field refers to the arena (or social setting, such as ritual [church], in which a specific habitus is deployed.

Cultural Capital

Cultural capital can exist in three forms: in the embodied state; in the objectified state, i; and in the institutionalized state. Cultural capital that is convertible, in certain conditions, into economic capital and maybe institutionalized in the form of educational qualifications (and who has access to education). Bourdieu and Passeron developed the concept of cultural capital in order to examine the impact of culture on the social stratification system and the relationship between action and social structure. In its embodied state, cultural capital is a form of long-lasting dispositions of the mind and the body (Bourdieu, 1986, p. 243). In other words, it can be understood as the legitimate cultural preferences and behaviors that are internalized mostly during the process of socialization. In turn, the institutionalized cultural capital can be associated with products or signals such as the educational degrees and diplomas that certify the value of the embodied cultural capital. Iin its objectified state, cultural capital represents the consumption and acquisition of several cultural goods (pictures, books, dictionaries, instruments, etc.).

Social Capital

Social capital is the aggregate of the actual or potential resources that are linked to possession of a durable network of more or less institutionalized relationships of mutual acquaintance and recognition – or in other words, to membership in a group that provides each of its members with the backing of the collectivity-owned capital. This is a ‘credential’ that entitles the members or agents to credit, in the various senses of the word. These relationships may exist only in the practical state, in material and/or symbolic exchanges which help to maintain them. Bourdieu’s concept of social capital focuses on conflicts and power relations that may be exposed by a closer look at social relations. Social capital can be perceived as a collection of resources that equals a network of relationships and mutual recognition, i.e., membership in a group. Also, for Bourdieu, social capital can be accumulated and deployed both collectively, for example by a family, and individually. It is mainly operationalized for tangible or symbolic gains. Thus, by being a member of an influential group of agents (members of a Greek society or university or college)or having a strong network of connections, one can monetize this situation for his/her own benefit. Thus, as a theoretical artifact, social capital engulfs the notion of social relations which increases the ability of an actor to advance her/his interests

Economic Capital

Bourdieu focuses on Marxian accounts of economic capital, such that it is purely individual material assets that can be directly and easily convertible into money or maybe institutionalized in the forms of property rights. Economic capital includes every form of material resources such as financial resources and land or property ownership. It consists of capital in Marxian terms, but it also engulfs other economic possessions that increase an agent’s capacities in society. However, Bourdieu does not define explicitly the notion of economic capital since he borrows this idea from the field of economics. He seems to merely offer a materialist interpretation of the notion; yet, this fact does not lead to a reductionist approach. He understands economic capital as a resource of paramount importance which, on one hand, distinct the agents who play the social game and, on the other hand, is unfairly distributed by being characterized by the law of transmission. Thus, economic capital manifests itself as the root of all other forms of capital which can be understood as disguised forms of economic capital.

The Code of Hammurabi (ca. 1754 BCE): The Appearance of Judicial Systems

The Code of Hammurabi appears to be the earliest codes of law preserved. The most famous is a 2.25 meter-tall diorite stela that exhibits a partial copy and consists of 282 laws. It is written in Assyrian cuneiform (wedge-shaped writing, one of the earliest forms of writing) and dates to circa 1754 BCE and represents one of the most complete corpus of early writing in the world. The laws are unique in that they have scaled punishments, which adjust severity based on social status and gender, especially slaves versus free persons and men versus women.

While there are several versions of the Code (written in clay tablets, etc.), the most famous is the diorite stela that was found in 1901 and then translated in 1904 by archaeologist/epigrapher Jean-Vincent Sheil. At the top of the finger-shaped stela is a depiction of Hammurabi receiving the law from Shamash, a version of the ancient Mesopotamian god of justice, morality, and truth. The laws were arranged in 44 columns and 28 paragraphs. About 100 laws related to transgressions or regulation of property and commerce, particularly related to debt, interest, and collateral. Another 100 related to family law such as divorce, inheritance, and incest.

While other law codes have been discovered, including the Code of Ur-Nammu , the Laws of Eshunna (ca. 1930 BCE), and the codex of Lipit-Ishtar of Isin (1870 BCE) as well as Hittite, Assyrian, and Mosaic law codes. These codes represent a shift in governance where even the previously semi-divine king would be beholden to these laws. These law codes originated in a very small geographic zone and appeared within a few hundred years of each other. Thus, the Code of Hammurabi represents a major turning point in our societal development. An effort was made to create a complete codex of law to address laws of dispute and societal control, but with scaled punishment depending on gender and social status.

One of the major interests of the Code of Hammarabi is the presence of lex talionis. Prior to the discovery of this stela, most scholars believed that this concept originated in Mosaic Law of the Old Testament era. The display of the laws throughout the kingdom of Babylon would have also been a component of the rule of the king, but also may be indicative of a level of literacy throughout the regime.

Concepts of Power

Political Power

Economic Power

Social and Ideological Power

Factionalism and Ideology

References:

Fried, Morton H. 1967. The Evolution of Political Society: an essay in political anthropology. Random House, New York.

Service, Elman R. 1962. Primitive Social Organization: an evolutionary perspective. Random House, New York.

Key Takeaways

- Fried and Service developed similar patterns of understanding the development of social organization.

- Bordieu’s forms of capital include cultural, social, and economic.

- City states represent one of the most pervasive forms of social organization from the early appearance of cities until the post-Renaissance period in Europe.

- Norman Yoffee’s power domains help us understand different roles control of political, economic, and social/ideological domains are used particularly in city states. These are very similar to Bordieu’s forms of capital.

- The Code of Hammurabi is one of the earliest and most complete codes of law and punishment for early city-states.

The power of the unit of two (also called a dyad) is the minimal social unit for interaction.

Agency is defined as the capacity of individuals (or agents) to act independently and to make their own free choices. By contrast, structure are those factors of influence (such as social class, religion, gender, ethnicity, ability, customs, etc.) that determine or limit an agent and their decisions.

This term is primarily from sociology, but is used extensively in political anthropology. Habitus In sociology, Habitus refers to the socially ingrained habits, skills and dispositions of an individual. It is the way that individuals perceive the social world around them and how they react to it. These dispositions are usually shared by people with similar backgrounds (such as social class, religion, nationality, ethnicity, education and profession). The habitus is acquired through imitation (mimesis) and is the reality in which individuals are socialized, which includes their individual experience and opportunities. Thus, the habitus represents the way group culture and personal history shape the body and the mind; as a result, it shapes present social actions of an individual.

For Bordieu, a field is a setting in which agents and their social positions are located. The position of each particular agent in the field is a result of interaction between the specific rules of the field, agent's habitus and agent's capital (social, economic and cultural). Fields may interact with each other, and are hierarchical: most are subordinate to the larger field of power and class relations.

The form of long-lasting dispositions of the mind and body

Cultural capital can exist in the form of cultural goods (pictures, books, dictionaries, instruments, machines, etc.), which are the trace or realization of theories or critiques of these theories, problematics, etc.

A form of objectification that must be set apart because, it confers entirely original properties on the cultural capital which it is presumed to guarantee.

The code is named for the sixth king of Babylon (in modern-day Iraq), Hammurabi. He ruled from 1792 to 1750 BCE.

An epigrapher is a scholar that studies epigraphy or the study of inscriptions, or epigraphs, as writing; it is the science of identifying graphemes, clarifying their meanings, classifying their uses according to dates and cultural contexts, and drawing conclusions about the writing and the writers.

King of Ur, in modern southern Iraq, ca. 2050 BCE.

Eshnunna (modern Tell Asmar in Diyala Governorate, Iraq) was an ancient Sumerian (and later Akkadian) city and city-state in central Mesopotamia. Although situated in the Diyala Valley north-west of the main city-state of Sumer.

Lipit-Ishtar, the king of Isin around 1900 BCE, who was powerful enough to proclaim himself king of Sumer and Akkad.

The Hittites were an Anatolian (roughly modern day Turkey) people who played an important role in establishing an empire centered on Hattusa in north-central Anatolia around 1680-1650 BCE. This empire reached its height during the mid-14th century BC under Šuppiluliuma I, when it encompassed an area that included most of Anatolia as well as parts of the northern Levant (eastern Mediterranean) and Upper Mesopotamia (modern northern Iraq).

Assyria, also called the Assyrian Empire, was a Mesopotamian kingdom and empire of the ancient Near East in the area today known as the Levant that existed as a state from perhaps as early as the 25th century BC (in the form of the Assur city-state) until its collapse between 612 BC and 609 BC — spanning the periods of the Early to Middle Bronze Age through to the late Iron Age.This vast span of time is divided into the Early Period (2500–2025 BC), Old Assyrian Empire (2025–1378 BC), Middle Assyrian Empire (1392–934 BC) and Neo-Assyrian Empire (911–609 BC).

The Law of Moses, also called the Mosaic Law, primarily refers to the Torah or the first five books of the Hebrew Bible. Traditionally believed to have been written by Moses, most academics now believe they had many authors.

the law of retribution or “eye for an eye and tooth for a tooth” laws

Babylon was the capital city of the ancient Babylonian empire, which itself is a term referring to either of two separate empires in the Mesopotamian area in antiquity. These two empires achieved regional dominance between the 19th and 15th centuries BC, and again between the 7th and 6th centuries BC. The city, built along both banks of the Euphrates river, had steep embankments to contain the river's seasonal floods. The earliest known mention of Babylon as a small town appears on a clay tablet from the reign of Sargon of Akkad (2334–2279 BC) of the Akkadian Empire. The site of the ancient city lies just south of present-day Baghdad in modern day Iraq.