11 Elements of Music: Overview

We have talked and listened to music as being something that is expressive and emotional. To help you understand the ways in which music moves us so that you could create your own music, you need to understand how music ‘works’ – the theory behind music. Musicians actually will speak of music theory in the way that a novel writer might discuss grammar or syntax, or a professional athlete might study and work on technique.

Introduction

An artform can be viewed as consisting of interrelated elements. For example, visual art can be described as involving elements such as color, line, and shape. A movie can be broken down into elements such as character, plot, and dialog. Music also has elements which can be described both in scientific and artistic terms.

The study of the physical properties of sound (acoustics) involves concepts important to music as an artform. While each element can be scientifically measured, the more important aspect is each element’s ability to be expressive in an artistic sense.

We shall view music as involving the expressive elements of texture, timbre, rhythm, melody, harmony and form.

When composers and performers deal with the elements of music, they must balance each so as to create a work and performance which has similarity and contrast, expectation and surprise.

Texture – Timbre

Texture is an element of music that involves aspects such as the type of instrument/voice being used, as well as the number of instruments heard at one time. Under this element, we will also include timbre (the characteristic quality of a sound), articulation (the manner in which the sound begins and ends – attack and release), and of course texture (characteristic quality of sound combinations).

The quality of a sound is acoustically described as the sum of its frequencies and is given the name of timbre (pronounced ‘tam-ber’). Complex sounds (i.e. any traditional instrument) are really combinations of many frequencies, each called an overtone. The only instance where a sound is just its base frequency (also called the fundamental) is a sine wave and can only be created electronically.

Even though timbre involves sounds with more than one frequency, the ear does not perceive individual pitches, but rather one pitch (determined by the lowest frequency – the fundamental) with a particular quality. Thus a violin and a clarinet playing the same note have the same fundamental, but a different combination of frequencies above that fundamental.

When working with electronic sounds and songs, composers often spend a lot of time and effort in working on the timbres as well as the way these instruments are combined to form texture.

Overtone Series

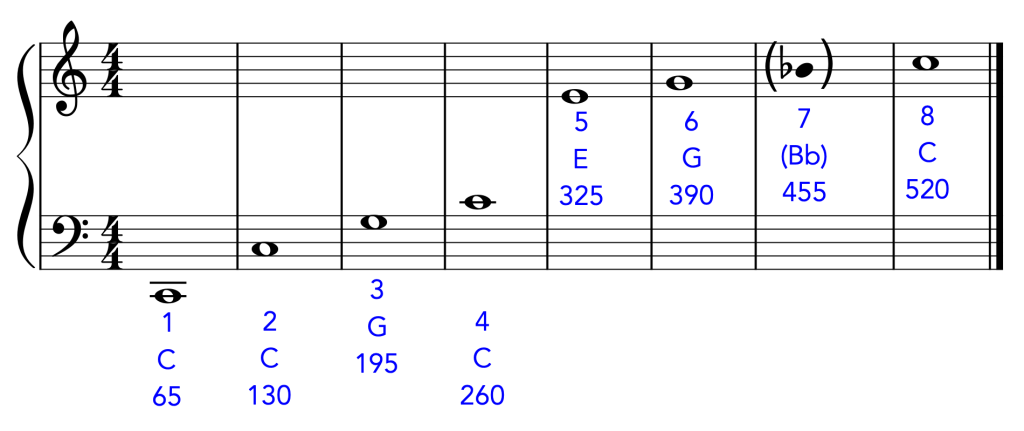

If we take a string that is say 10 inches, and pluck it we would get a sound. If we then cut the string in half (5 inches) and pluck it again, we would hear a pitch that is one octave higher than before (twice the cycles per second). There is a mathematical relationship between string length and frequency of sound heard which results in what is known as the overtone (or harmonic) series. A string’s frequency is inversely proportional to its length, thus if string X is one half of Y, its pitch will be twice that. Here’s what that would look like over 8 notes:

Look at the first three notes that have different pitch (letter) names – you’ll note them as numbers 1 (C) 3 (G) and 5 (E). This is exactly the same three notes if you were to create a chord, based in tertian harmony, starting on a C.

Practice: Logic Pro – Timbre & Software Instruments

Logic Pro comes with literally hundreds of software instruments which can be combined to create new timbres and textures.

- Start a new Project with “Empty Template”

- Choose “Software Instrument” for the initial track – be sure “Show Library” is checked

- Try out various software instruments

- Create additional tracks (use Track menu) with different instruments

- Use the NotePad to jot how you made the decisions you did…

Practice: Pro Tools Intro – Timbre & Software Instruments

Pro Tools Intro comes with literally hundreds of software instruments which can be combined to create new timbres and texture

- Start a new Session

- In Browse mode, select “Instruments” for the initial track – drag over the desired instrument to the work area

- Try out various software instruments (via the QWERTY virtual keyboard)

- Create additional tracks (use Track menu) with different instruments

- Use the Track Comments to jot how you made the decisions you did…

Practice: Logic Pro – Texture & Track Stack Overview

- Start a new Project with “Empty Template”

- Add two tracks of different timbres

- Select the tracks and then use the “Stack Track” feature to create a summing track*

- Use the new track as a new patch.

*In Logic Pro, be sure Advanced Tools are on

Practice: Pro Tools Intro – Texture & Track Stack Overview

- Start a new Session

- Add a track via the Window ➤ New Workspace ➤ Track Presets (use Xpand!2)

- Open the Xpand!2 instrument by clicking the grey insert button

- Use the PART controls to add additional timbres to this instrument

Rhythm

In looking at rhythm as a musical element capable of meaning, we must discuss two aspects – beat (or pulse) as constant rhythm, and then the use of rhythm for musical ideas or motives (patterns). In non-musical settings, we tend to measure duration in units of time. The selection of the unit of measurement depends on the measurement scale we wish to use. For example, if one were to measure how long it takes to run the mile. we use the minute as the standard. We don’t speak of a .066 hour mile or the length of a class as lasting .0625 of a day. We select a unit of measurement which makes sense. The other concept to consider is that when measuring duration, there is a unit which becomes the standard. The unit of measurement does not change (i.e. a second today last as long as a second will tomorrow).

When duration is considered in a musical context, we again must have a standard unit of measurement. This standard is referred to as the beat or pulse. Most music around us has an underlying, constant pulse or movement, much the same way that our heart is constantly beating, even when we are unaware of its activity. The natural pulses of our body are excellent examples of tempo – constant, even measurements of time. Rhythmic pulse, both in nature and music, is never always at the same pace, but undergoes changes. If we are running, our heart beats faster – but still at a constant rate. The same is true when we are sleeping, for while our pulse is much slower, it is still a constant measurement of time.

Rhythmic Pulse

Tempo in music contains meaning for us as well as having certain expectations. Many people would equate slow music with relaxation, and fast music with excitement. While this is obviously an oversimplification, there is a bit of ‘common’ sense and experience to that idea. If musical pulse is viewed as a series of steady beats, given our discussion of expectation and perception, it would not have sufficient information for us due to its lack of structure and organization. Such a phenomenon would quickly bore the ear, as well as the composer and performer! We all tend to organize pulse around a meter, or the stressing of a specific pulse number. If every other pulse received stress (1 – 2 – 1 – 2), this would be considered duple meter. Every third pulse (1 – 2 – 3 – 1 – 2 – 3) would be triple meter. All music can be broken down or reduced to some combination of duple and/or triple meter. If the number of beats within a set, or measure is divisible by 2, then the meter is duple. Five beat measures could be conceived as one “submeasure” of duple plus one “submeasure” of triple. Some examples:

“Viennese Musical Clock” from Hary Janos Suite. The opening has bells which clearly outline a duple meter with four beats to the measure.

“Waltz” from Jazz Suite No. 2. This piece by a Russian composer uses a triple meter common in all waltzes. The accents on beat one can be clearly heard throughout the work, especially in the opening measures where basses play on beat 1 and the higher strings play beats 2 and 3.

“Mars, the Bringer of War” from The Planets. This movement has a meter involving five beats to the measure. This will note that it can be broken down to a 3 + 2 combination. The pulse is constantly driving. “Holst remarked that he wanted to express the stupidity of war: the pounding rhythm, occasionally giving way to a mindless swirling effect, admits of no compassion; the drive is as blunt as brutality itself”. (Notes by Richard Freed, program book of Saint Louis Symphony Orchestra)

We have only discussed so far rhythm in terms of a steady, unchanging standard of measurement or beat. Obviously, rhythm, if it is to be expressive, will need to involve sounds of various durations. Rhythm is usually conceived in terms of patterns upon which a piece is developed and or based. Rhythm in and of itself is expressive, and many pieces have been written which primarily focus upon the use of rhythm by contrasting even and uneven patterns of sound durations.

Practice: Logic Pro – Rhythm & DrumKits

Logic Pro has three percussion formats: MIDI drum kits, drum loops, and the interactive Drummer. For our purposes, we will focus on MIDI drum kits.

- Start a new Project with “Empty Template” using a software instrument for the initial track

- Change the instrument to a DrumKit

- Go to the editor, and on the left side you can view all of the different instruments in the kit

- Use “Step Sequencer” to control precise adding of drum hits via a grid into a ‘pattern region’

Practice: Pro Tools Intro – Rhythm & DrumKits

Pro Tools Intro has two percussion formats: MIDI drum kits, and Percussion Instruments. For our purposes, we will focus on MIDI drum kits.

- Start a new Session

- Add a track via the Window ➤ New Workspace ➤ Track Presets from the Drum Kits folder

- Double-click a drum kit (for example, RockKit)

- Display the MIDI Keyboard via Window ➤ MIDI Keyboard.

- Enable the record option on the track to hear the various drum sounds – Note that each note is an entirely different sound from the drum kit… You’ll want to use the Octave Up (X) and Octave Down (Z) to expand to hear more sounds.

- Drum Kits only use a limited number of notes so don’t worry if very high or very low keyboard notes have silence.

Harmony

Harmony is viewed as pitches heard all at the same time (vertical) as opposed to melody where pitches are hear in succession (horizontal). The historical period in which the music was written also will provide information as to the harmonic vocabulary of the piece. This element of music is the traditional focus of music theory courses, and in many instances, provides an underlying structure for a piece around which the other elements operate.

Tonal Center

When we hear a person say things like “That didn’t sound so good, are you in the right key?”, they are referring to the concept that one particular pitch or tone is the center around which all other pitches are structured. This tonal center can be considered the “main idea” in a melody in terms of the pitches which the composer uses. While every composer, including yourself, has 12 pitches available, seldom does he or she use all 12. (Imagine having to use every color available to you every time you created a painting). We shall look at a specific structure or system for selecting pitches called tonality.

Since we don’t want to get ahead of ourselves and discuss notation and vocabulary before we’ve had a chance to listen and think musically, let’s just say for now that the combination of tones we’ll use is simply all white keys of the piano (this is a major scale which we all know intuitively the sound of). We now have 8 instead of 12 notes available to use which we’ll number 1 through 8 and look like the following:

The first scale degree (in this case ‘C’) can be considered as the most important pitch in the same way that when we look at meter, we considered the first beat in each measure to be important and be stressed. The tonal center or tonic (scale degree number 1) is what is being talked about when a piece is said to be in a specific key. The Beethoven 5th Symphony in C Minor means that C is the tonal center and a minor (as opposed to major) scale is being used – more about scales later! As you listen to pieces which are tonal (99% of the music you hear around you!), you will notice how obvious the tonal center is to hear.

Organization

Some ground rules and assumptions are in order when we start talking about harmony (notes sounding at the same time). First, we are obviously talking about more than one note, and second, we usually assume that the notes are different. If I play two notes on the piano which I’ll call X and Y, and they are the same letter name but different octaves, we usually consider them to be, for the purposes of harmony, the same note. An octave can be described as the relation between the frequencies of two notes. If the ratio of cycles per second (cps) of X to Y is a multiple of two (1:2 or 1:4) then the two pitches will have the same letter name and differ only in their octave. For example, the pitch A at 440 cps is one octave above the A at 220 cps and 4 octaves above the A at 110 cps. Since the shape of the waves would complement each other, our ear perceives octaves as “pleasant” and sometimes as the same note.

A second ground rule is that two notes at the same time is called an interval while more than two notes is a chord. Note that we don’t need any further description (i.e. what kind of interval, or what kind of chord). If you place your entire arm on the piano and play 10 notes at once, it will still be a chord, and a very unique one at that!

Music of western cultures in the European and American tradition is built on tertian harmony or chords built on pitches that are three notes apart, counting the beginning note as one (i.e. A B C D E – 1 2 3 4 5). This system of harmony, as with the tonal center concept in melody, is one that you intuitively know through experience. Most of the music you listen to is this system of harmony.

Harmony as Vocabulary

The use of harmony by composers usually involves a certain harmonic style or vocabulary. We talk of a piece being major or minor – what we are referring to is the specific system of chords and harmonic vocabulary being used. It is possible to imagine that the number of possible chords is infinite, given that a chord is simply three or more notes at once. In practical terms, many, many combinations of chords are possible, but not all can be used. This is the same reasoning why in melody, we limit our choices from 12 notes to 8 as an organizing scheme. Historically, harmony has undergone great change and development as one’s ability to hear more complex chords improved. Let’s consider some examples.

An early piece such as the Canon in D by Johann Pachelbel is an excellent example of a work which uses a minimal harmonic vocabulary (8 chords). Each chord has only three different notes, and all would be found in the scale with D as its tonal center (D E F# G A B C# D).

Contemporary uses of harmony attempt to stretch the possibilities. One example is a piece by an American composer Charles Ives – Variations on America. At one point in the work, he needs to move from the Key of F major to the key of D-flat Major – these two keys are not related at all, so, he simply uses both keys at the same time to create a transition from one to the other. In the video, the music in the key of F is highlighted in red, and music in the key of D-flat in blue.

Practice: Logic Pro – Harmony & MIDI FX

There are several MIDI effects (MIDI FX) that can be helpful to experiment with various chords and harmonic progressions

- Select a track with a software instrument.

- Select the “Inspector” to reveal the control strip. (Also can be found in the View Menu as “Inspector”)

- There is a greyed out control labeled “MIDI FX” – try the following… For each, when you select a FX, a new window with controls will appear – input note(s), using either Musical Typing or an external device, to hear the effect

- Arpeggiator

- Chord Trigger

- Note Repeater

- Transposer

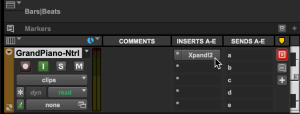

Practice: Pro Tools Intro – Harmony & MIDI FX

There are several MIDI effects that can be helpful to experiment with various chords and harmonic progressions. NOTE: be sure you have downloaded and installed the MIDI Effects Plugins…

- Create a track with an instrument of your choice.

- Click on an empty “INSERTS A-E” and select MIDI Plugin ➤ Note Stack

- Drag the dial on Note 1 to “4st” (4 half steps). The Note 1 button turns active.

- Click Note 2 and leave the dial at 0st

- Play the MIDI Keyboard and you’ll hear two notes (the note you play and one that is 4 half steps higher!)

- Use the Preset popdown to try some more sophisticated settings.

Melody

We can measure the highness or lowness of a sound by counting its vibrations or cycles per second (cps). While sounds can and do exist at all frequency levels, in music in the Western (European) tradition, only discrete frequencies are used. We typically think and hear melody as ‘the tune’ – and in lots of pop music, it is the melody that also has lyrics.

In the expressive sense, we can view melody as a succession of pitches, again with a degree of structure and contrast as well as expectations. We usually view melody relative to one pitch which becomes a standard, or ‘home tone’. This home tone (referred to as the tonic) is what is meant when we talk about a melody being in a certain key. The concept of a key or tonic is simply a form of structure – call any pitch the tonic, and immediately there exists a set of possible pitches to use in creating a melody.

An important aspect of melody is that of ‘contour’ – the overall shape of a melody. We actually hear shape and contour more than individual notes… Here’s proof!

Remember the “Mystery Song” from an earlier chapter? It was a demonstration of the importance of contour in melodies.

| Mystery Song (listen to this version first!) | |

| Original Song (in multiple octaves) |

Practice: Logic Pro – Melody & MIDI FX (Transposer)

In this practice session, we will ‘transpose’ an instrument so that it only plays notes in a specific scale to make sure a melody ‘fits’.

- Select a track with a software instrument.

- Select the “Inspector” to reveal the control strip. (Also can be found in the View Menu as “Inspector”)

- In the ‘info’ strip, select the MIDI FX popup and choose “Transposer”

- Use the Scale popup to change from Chromatic to Major (try others as well) – this transposes the keyboard or input device to ONLY use notes in the scale regardless of what you play!

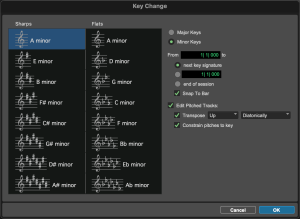

Practice: Pro Tools Intro – Melody & Apply Scale

In this practice session, we will ‘transpose’ midi region so that it only contains notes in a specific scale to make sure a melody ‘fits’.

- Select a track with a software instrument.

- Add some midi content

- Use the menu item Event ➤ Add Key Change

- Check “Edit Pitched Tracks” as well as “Constrain pitches to key”. This will ensure that your melody ideas stay within the selected key.

Harmony and Melody as Related Elements

As we have seen so far, melody and harmony are related in as much as we can conceive of both involving pitch – melody the horizontal (linear) occurrence of pitches and harmony the vertical (simultaneous) occurrence of pitches. Now we want to discuss some ideas that are shared by both elements as well as reviewing some of the terms we have previously mentioned.

Tonality

Tonality refers to the organization of pitch around a central note (the tonal center). In practical terms, this is what we refer to when one talks about the key of a piece. A fundamental (and perhaps obvious) concept is that given any key, the same set of pitches is used when creating melody and harmony within the same piece. Contemporary composers have violated this concept as a way of writing atonal (not tonal) music by writing a melody in one key and using harmony, at the same time. in another. The overall effect is the “clashing” of two systems of organization resulting in two simultaneous tonal centers thus causing confusion to the ear.

Implied Harmony

Even though melody is horizontal and only one note at a time is heard, our ear, combined with our memory, can actually perceive what is referred to as implied harmony. We tend to remember, and then compare, the pitch we are currently hearing with what was just heard, and if the relationship is obvious enough, we can “hear” a specific chord. Prelude No. 1 in C from the Well-Tempered Clavier by J. S. Bach is an excellent example of implied harmony as even though only the first two pitches in each figure are actually held, one can clearly tell when the “harmony” changes. Another example is any typical bugle call. Because of the way the instrument is made, only notes that can be found in the overtone series are possible. (A bugle in B flat can only produce the notes in the B flat overtone series, etc.) Thus any melody played on a bugle is automatically organized around one pitch and therefore implies the tonic chord or harmony.

Another technique is that of rapidly alternating between notes common to a chord. Remember from our discussion of acoustics that notes 1, 3, and 5 from a scale together create a tonic chord (chord based upon the tonal center). Imagine a melody which only uses those three notes, but in rapid succession such as: 1 5 3 5 1 5 3 5 etc. Guitar players use this approach all the time when they are accompanying themselves. (This, by the way is not my invention! You can see (and hear) that such melodic patterns can indeed actually imply harmony.

So here’s a demonstration of this notion of melody implying harmony using the Prelude No. 1 in C that was mentioned earlier.

Form

Form refers to the structure of a given piece and will involve all of the elements of music we have mentioned. Form can be compared to the concept of a novel having a plot around which details occur. The plot provides the overall structure of the work and form in music functions in a similar manner. Again, historical periods of music developed and used specific forms, which follow patterns and conventions.

Popular Song Form

Popular music uses form to provide important repetition for the listener to learn the song quickly. Some of these sections can include:

Intro: often instrumental only which may also provide something that immediately captures the listener’s attention and sets up the feel or mode of the song.

Verse: The primary section of a song that ‘tells’ the story of the lyrics. Songs may have multiple verses with the only difference being the text (lyrics). Sometimes subsequent verses have slight differences in texture or accompaniment or key (verse 3 a half step higher for example)

Refrain: a line that is repeated at the end of each verse – often used to ‘connect’ to the Chorus.

Chorus: typically the ‘hook’ or most memorable part of the song, usually due to its simplicity, either in text or melodic construction. The chorus is the part of the song you’ll leave humming…

Bridge: an optional transition that usually occurs only once, near the end of the song. For example it may replace a verse in a ‘verse-chorus’ form, or between repeats of a chorus. It can also be an instrumental only ‘break’ with no lyrics.

Coda (or Extro): final part of a song, sometimes an instrumental version of the ‘hook’ from the chorus. Balances the ‘intro’ as the last thing the listener will hear.

Practice: Logic Pro – Form & Arrangement Track

The “Arrangement” Global Track easily lets you label, organize, and even rearrange the sections of your music.

- Start a new Project with “Empty Template”

- Use the Track menu to “Show Arrangement Track” – note the keyboard shortcut…

- Add sections using the ‘+’ button.

- Click the title of a section to change/edit it.

Note how the cursor changes depending upon where it is in the title bar of the section – you can shorten, lengthen, and/or move.

Practice: Pro Tools Intro – Form & Arrangements

There are two approaches to working with your music in sections as you think about form.

- Use Markers to indicate the beginning (and end) of sections. You can use labels such as “Intro” or “Chorus”. Then use the Window ➤ Memory Locations to display a mini-window with all of your makers. You can quickly navigate throughout your project.

- Instead of Session, create a project that is a Sketch. You will note an ARRANGEMENT tool at the top of the screen where you can drag and drop in Scenes to create a more involved piece.

Final Thoughts

In our future discussions and experiences with these elements of music, it will be important for you to understand these ideas through ‘hands-on’ experiences of listening, performing and composing. In this, the interrelationships will become more apparent, and at the same time, will provide you with knowledge and experiences so that you can better shape the direction you would like to go in your aesthetic experiences with music.

tertian describes harmony, chords, or melody constructed from the intervals of thirds.

two pitches played at the same time OR the distance between two pitches (such as a minor third, or a perfect fifth)

three or more notes typically sounding at the same time (but not required)