8 Music & Aesthetics

“Where words leave off, music begins.” – Heinrich Heine

Introduction to Aesthetics

Given the idea that meaning in art only comes if we, as the perceiver, have sufficient knowledge (expectations) and experience so as to ‘make sense’ of the artwork, it would follow that if our expectations are too easily met, aesthetic or artistic meaning will be at a very elementary and superficial level.

In an aesthetic experience, we need an artwork (a piece of music), and a perceiver (you as listener/performer). You perceive the artwork and then have reactions to it. (This is also a description of basic ‘survival’ perception – you see a red light, so you stop. When it turns green, you proceed.) What makes for aesthetic perception is the continuous and cyclical reactions/perceptions. Your reactions to the artwork now affects and changes your perceptions, giving you ‘newer’ perceptions and hence a new set of reactions. This give and take process continues between the artwork and yourself. Obviously, this process takes time and involves energy, feelings, emotions, (and sometimes effort!)

The quality of your perceptions/reactions are in part dependent upon your experiences and knowledge (as discussed earlier) and your attitude towards the specific aesthetic experience. The context or environment can play a crucial role. For example, one usually does not ponder and react over a piece of office furniture. However, if you were at a gallery, and, as an exhibit, the same piece of furniture was presented, you would approach the experience of looking at it differently – you would have a more ‘aesthetic’ approach.

Watch the next video for an example where a photo trying to capture a beautiful natural setting could yield an aesthetic experience. The more the person perceives the thing, the greater the quality and quantity of reactions. As the cycle of perception/reaction continues, the greater the potential for an aesthetic experience that improves in quality.

Aesthetic Perception & Reaction

Approaches

We can summarize various positions or approaches to any perceptual situation as (1) technical, (2) practical, (3) religious, and (4) aesthetic. The technical approach enters the listening of music with a concern as to the ‘how’ of the performance and matters related to the technical side of music. An individual who is studying piano and listening to a performance of a Beethoven piano sonata might attend to the fingering used by the artist, or the manner in which his or her sparkling technique must have taken years to develop. The analysis of music from a theoretical perspective could be included here.

Music perceived via a practical approach is usually secondary to some other occurrence. The music in elevators or doctors’ offices is not intended to demand our full attention, but rather as background. The dentist doesn’t want you to be expending energy listening to acid rock in anticipation of having a molar drilled! Music for special ceremonies or sporting events is used to serve a purpose, thus one does not usually associate such events as aesthetic in nature. In such situations while there usually is music, it is designed to be low in the need for effort in its perception as well as low in the thwarting of expectations. The music is typically not the focal point.

A religious approach to the listening of music is a response which does not focus upon the expressive qualities of the music itself, but rather to ideas, concepts or feelings associated with religious aspects, especially when lyrics/text is involved.

An aesthetic approach is one where the expressiveness of the elements of music form the basis for the perception – reaction cycle. It is this approach about which we want to continue our discussion.

The quality of your perceptions/reactions will also be dependent in part on the quality of the artwork itself. If your expectations are constantly met, the net effect will be boredom. Compare a Beethoven symphony with a simple pop tune. The symphony has much more content of greater complexity than what one typically hears in popular music. The relative simplicity of a pop tune is what helps to make it popular – it is easy to listen to, understand, and remember, and often after only a few hearings. An artwork needs a careful balance of structure, unity, and expected ‘norms’ with contrast and ‘surprises’.

Very serious contemporary music is sometimes of such a complex nature and structure, that it demands an incredible amount of previous knowledge and experience to fully react to all that the piece has to offer. Such intensity is very often beyond the desires of the average listener.

Here are some pieces presented in order of complexity to the listener (least complex first) – Notice that they were all composed around the same time period in history.

| Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On – composed 1957 |

|

| Theme from Star Trek (composed 1966) |

|

| Mambo from West Side Story: Symphonic Dances (composed 1960) |

|

| Atmosphères (for large orchestra) (composed 1961) |

|

Questions…

- Do you agree that these pieces are in order of complexity? Why or why not?

- Without using titles, or composer names, and without singing anything, how could you describe each piece so that someone who has heard them would recognize the one you’re talking about?

Aesthetic Approaches

Within the aesthetic approach to listening, there exists various theories as to how aesthetic perceptions and reactions are developed. One such view, referentialism, holds that the value of music lies in its reference to things outside and beyond the music itself. The Fantastic Symphony by Hector Berlioz is an example of a musical work conceived by the composer to be closely linked to a story. This story line is considered so important that the composer instructed that whenever the symphony is performed, the story should be printed in the audience’s program.

An opposite view, that of formalism, holds that the value of any musical work are the ideas expressed by the composer. Furthermore, these ideas are primarily of a purely musical nature.

The middle ground between these two extremes is that of absolute expressionism which accepts the value of the formal properties of a work of art, but also holds the notion that such properties may need to be considered relative to some non-musical aspect of human life.

The major function of art is to make objective, and therefore conceivable., the subjective realm of human responsiveness. Art does this by capturing and presenting in its aesthetic qualities the patterns and form of human feelingfulness… Aesthetic education, then, can be regarded as the education of feeling. (Reimer, a philosophy of music education, 1970:39).

Views of Musical Perception

Since perception is at the heart of an aesthetic experience, some discussion of how we perceive is helpful. Perception is often different from reality as can be shown by optical illusions. We organize our perceptions, especially those that are auditory, based in part on our past experience and our present knowledge.

Let’s look at a few illustrations regarding visual perception and then make the connection to aural and musical perception.

We make connections and sense relationships through our perceptions via concepts such as closure, proximity, and common fate. Let’s listen to excerpts by two composers, Ludwig van Beethoven (Symphony No. 5 in C minor) and Johann Sebastian Bach (Giga from Partita No. 1 in B flat Major, BWV 825).

Listen to this excerpt and answer the question…

Is this audio clip major or minor?

If you said minor, your past experience is probably at work as indeed, this is a pretty famous piece. It is by Ludwig van Beethoven and is his Symphony No. 5 in C Minor. So yes, the piece is in minor, but the clip is actually neither as insufficient melodic content is present to determine major vs. minor.

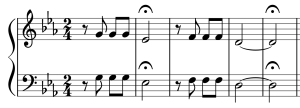

Here’s a score snippet of the opening five measures.

The orchestra is in unison, and only play four pitches: G Eb F D. These pitches on their own don’t indicate C minor (there is no C) nor Eb major. But you’ve heard the piece enough times that your past experience hears C minor. Your ears have “filled in the gaps” of ‘missing notes’ that would indicate major vs. minor as an aural example of ‘closure’.

The orchestra is in unison, and only play four pitches: G Eb F D. These pitches on their own don’t indicate C minor (there is no C) nor Eb major. But you’ve heard the piece enough times that your past experience hears C minor. Your ears have “filled in the gaps” of ‘missing notes’ that would indicate major vs. minor as an aural example of ‘closure’.

To make this point, note that the opening bars could have been written moving to either Eb major or C minor as you can hear in these contrived examples in the following video…

In the actual opening of the symphony, the real key of C minor doesn’t appear until the 7th measure when the bassoon and cello enters playing a C which is the tonic note.

Proximity / Common Fate

Here is an example of both proximity and common fate that we heard in a previous section. While the piece is written for a single keyboard player, you will be able to hear three parts: (1) a melody line consisting of short (often only two note) phrases, (2) a bass line that mirrors the melody line and (3) a middle range triplet accompaniment.

This version is played on the piano while the video version (with notation) has been realized on a synthesizer, using different timbres (instruments) to help you hear the three different parts. The closeness of the pitches in terms of range (proximity) as well as the contour of the musical phrases (common fate) help to provide this sense of multiple parts within a single piece.

Questions…

- Can you think of musical examples that demonstrate “closure”, “proximity” and/or “common fate”?

a set of principles concerned with the nature and appreciation of beauty, especially in art. Also a branch of philosophy that deals with the ideas of beauty and artistic taste.

a perspective on the aesthetic perception of art that the value of a musical work lies, in part, in its reference to things outside and beyond the music itself

a perspective of musical perception where the value of a musical work are the ideas expressed by the composer, primarily of a musical nature, with little or no external connections

accepts the formal properties of a work of art, but also holds that these properties may need to be considered to non-musical aspects