II. Counterpoint and Galant Schemas

22

Kris Shaffer and Mark Gotham

Key Takeaways

- Species counterpoint is a step-by-step method for learning to write melodies and to combine them.

- While the "rules" involved are somewhat linked to music in the 16th century, the idea really is to train basic skills, independent of a specific repertoire or style.

- This chapter recaps some key concepts we met in the Fundamentals section and introduces some basic "rules" that will be relevant for each of the following chapters, including some terms for:

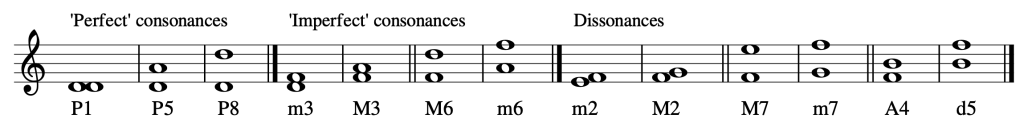

- Consonance and dissonance:

- Perfect consonances: perfect unisons, fifths, and octaves

- Imperfect consonances: major and minor thirds and sixths

- Dissonances: all seconds, sevenths, and diminished and augmented intervals

- Types of two-part motion:

- Contrary: the two parts move in opposite directions (one up, the other down

- Similar: the two parts move in the same direction (both up or both down)

- Parallel: the two parts move in the same direction (both up or both down) by the same distance, such that the starting and ending intervals are of the same type (e.g., parallel thirds)

- Oblique: one part moves, the other stays on the same pitch

- Consonance and dissonance:

We begin with a specific method called species counterpoint. The term "species" is probably most familiar as a way of categorizing animals, but it is also used in a wider sense to refer to any system of grouping similar elements. Here, the species are types of exercises that are done in a particular order, introducing one or two new musical “problems” at each stage. (So no, we won't have any elephants or monkeys singing polyphony, sorry!)

While there are many variants on this approach, the chapters here are closely based on Johann Joseph Fux's Gradus ad Parnassum (Steps to Parnassus, 1725). Many composers from the 18th to the 21st centuries have used this method, or some variation on it. In the first part of Gradus ad Parnassum, Fux works through five species for combining two voices, which will be the focus of our next five chapters. The “Gradus ad Parnassum” Exercises chapter provides all of the exercises from Gradus ad Parnassum in an editable format so you can try this yourself.

Before getting into the five species, we begin in this chapter by introducing principles that apply to writing lines in any species. These principles build on concepts from the Fundamentals section, such as intervals and scale degrees.

Consonance and dissonance

Consonance and dissonance was introduced in a previous chapter, but in counterpoint, we further distinguish between:

- Perfect consonances (perfect unisons, fifths, and octaves)

- Imperfect consonances (major and minor thirds and sixths)

- Dissonances (all seconds, sevenths, and diminished and augmented intervals)

These categories are summarized in Example 1 below.

The elusive perfect fourth

As in many theories of tonal music, the perfect fourth has a special status in species counterpoint that depends on where it appears in the texture. Basically, the interval of a perfect fourth is dissonant when it involves the lowest voice in the texture, but it is consonant when it occurs between two upper voices.

As this survey of species counterpoint will only cover two-voice textures, all fourths will involve the lowest part and therefore be classed as dissonant. Later chapters in this section will address the resolution of this dissonance, and the Strengthening Endings with Cadential [latex]^6_4[/latex] and [latex]^6_4[/latex] Chords as Forms of Prolongation chapters in the Diatonic Harmony section discuss this topic further.

Types of motion

Species counterpoint also concerns the motion between melodic lines (demonstrated in Example 2):

- Contrary: the two parts move in opposite directions (one up, the other down)

- Similar: the two parts move in the same direction (both up or both down)

- Parallel: the two parts move in the same direction (both up or both down) by the same distance, such that the starting and ending intervals are of the same type (e.g., parallel thirds)

- Oblique: one part moves, the other stays on the same pitch

Composing a Cantus Firmus

Exercises in strict voice leading, or species counterpoint, begin with a single well-formed musical line called the cantus firmus ("fixed voice" or "fixed melody"; plural "cantus firmi"). Cantus firmus composition gives us the opportunity to engage the following fundamental musical traits:

- smoothness

- independence and integrity of melodic lines

- variety

- motion (toward a goal)

Example 3 contains all the cantus firmi that Fux uses throughout Gradus at Parnassum: one for each mode, presented here in the upper and lower of two parts. Apart from using this to review the type of cantus firmi Fux composed, you can use this to practice any of the species, on any of the modes, and in both the upper and lower parts.

https://musescore.com/user/30425053/scores/5335420/embed

Example 3. Cantus firmi from Gradus ad Parnassum.

Notice how in each case, the general musical characteristics of smoothness, melodic integrity, variety, and motion toward a goal are worked out in specific characteristics. The following characteristics are typical of all well-formed cantus firmi:

- length of about 8–16 notes

- arhythmic (all whole notes; no long or short notes)

- begin and end on do [latex](\hat1)[/latex]

- approach final tonic by step: usually re–do [latex](\hat2-\hat1)[/latex], sometimes ti–do [latex](\hat7-\hat1)[/latex]

- all note-to-note progressions are melodic consonances

- range (interval between lowest and highest notes) of no more than a tenth, usually less than an octave

- a single climax (high point) that usually appears only once in the melody

- clear logical connection and smooth shape from beginning to climax to ending

- mostly stepwise motion, but with some leaps (mostly small leaps)

- no repetition of “motives” or “licks”

- any large leaps (fourth or larger) are followed by step in opposite direction

- no more than two leaps in a row and no consecutive leaps in the same direction (except in the F-mode cantus firmus, where the back-to-back descending leaps outline a consonant triad)

- the leading tone progresses to the tonic

- leading notes in all cases, including in "minor"-type modes for which that seventh degree needs to be raised

Melodic tendencies

Some of the characteristics listed above are specific to strict species counterpoint; however, taken together, they express some general tendencies of melodies found in a variety of styles.

David Huron (2006) identifies five general properties of melodies in Western music that connect to the basic principles of perception and cognition listed above, but play out in slightly different ways in specific musical styles. They are:

- Pitch proximity: The tendency for melodies to progress by steps more than leaps and by small leaps more than large leaps. An expression of smoothness and melodic integrity.

- Step declination: The tendency for melodies to move by descending step more than ascending. Possibly an expression of goal-oriented motion, as we tend to perceive a move down as a decrease in energy (movement toward a state of rest).

- Step inertia: The tendency for melodies to change direction less frequently than they continue in the same direction. (That is, the majority of melodic progressions are in the same direction as the previous one.) An expression of smoothness and, at times, goal-oriented motion.

- Melodic regression: The tendency for melodic notes in extreme registers to progress back toward the middle. An expression of motion toward a position of rest (with non-extreme notes representing “rest”). Also an expression simply of the statistical distribution of notes in a melody: the higher a note is, the more notes there are below it for a composer to choose from, and the fewer notes there are above it.

- Melodic arch: The tendency for melodies to ascend in the first half of a phrase, reach a climax, and descend in the second half. An expression of goal orientation and the rest–motion–rest pattern. Also a combination of the above rules in the context of a musical phrase.

Rules for melodic and harmonic writing

In species counterpoint, we both write and combine such melodic lines. The following set of rules invoked in all the species begins with the melodic matters discussed already, then presents some harmonic considerations that we will focus on in the following chapters.

Melodic writing (horizontal intervals)

- Approach the final octave/unison of each exercise by step (this creates the clausula vera).

- Limit the number of:

- consecutive, repeated notes: the same pitch more than once in a row

- non-consecutive repeated notes: the same pitch more than once across the whole exercise

- consecutive leaps: multiple intervals of a third or greater in a row (separate them with stepwise motion)

- non-consecutive leaps: the total number of leaps within a short span, even if they're not successive

- consecutive repeated generic intervals: the same interval size (e.g., second) even if not the same specific interval (minor second)

- Control the melodic climax (highest note):

- Aim for exactly one unique climax in each melodic part

- Avoid ending on that climax

- Preferably leap to that climax

- Avoid the two parts reaching their respective climax pitches at the same time

- Avoid melodic leaps of:

- an augmented interval

- a diminished interval

- any seventh

- any sixth, except perhaps the ascending minor sixth

- any interval larger than an octave

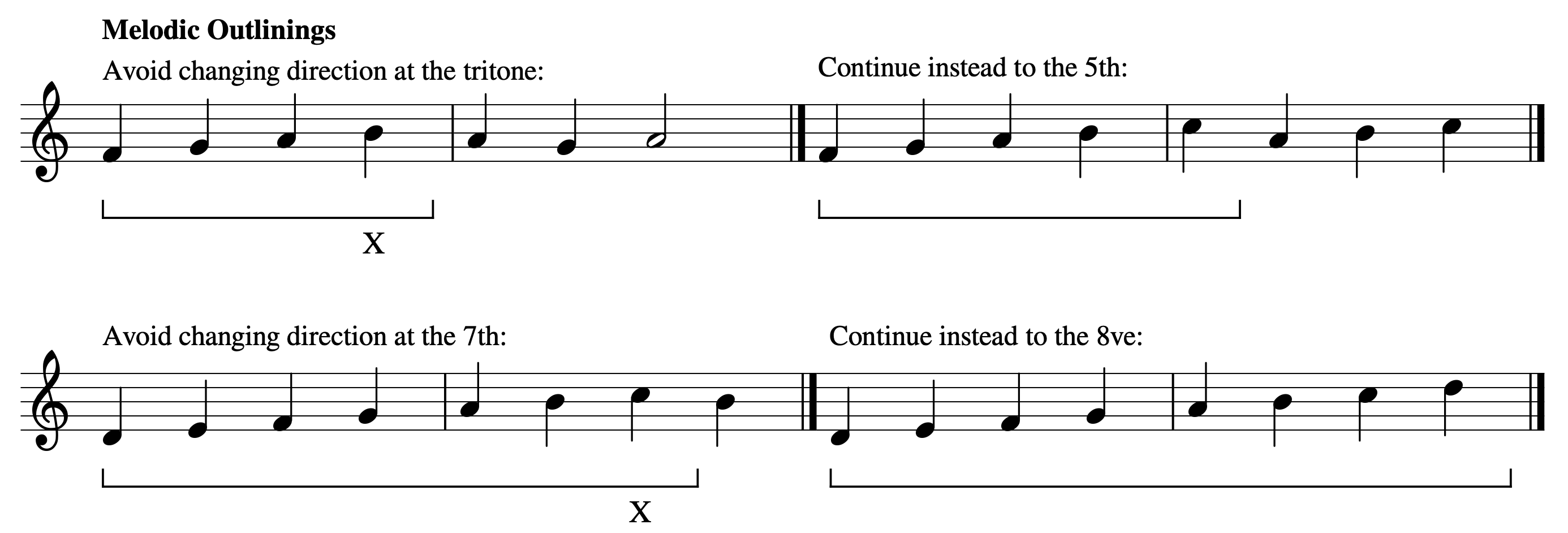

- Also avoid outlining (Example 4):

- an augmented interval

- a diminished interval

- any seventh

Harmonic writing (vertical intervals and the combination of parts)

- The first interval should be a perfect unison, fifth, or octave, and the last interval should be a perfect unison or octave (not fifth).

- Restrict the gap between parts to a twelfth (compound fifth) maximum, and to an octave for the most part.

- Avoid "overlapping" parts (where the nominally "upper" part goes below the "lower" one).

- Make sure to avoid:

- parallel octaves: when two parts start an octave apart and both move in the same direction by the same interval to also end an octave apart

- parallel fifths: when two parts start an perfect fifth apart and both move in the same direction by the same interval to also end a perfect fifth apart

- Also try to avoid:

- direct fifths and octaves: when two parts begin any interval apart and move in the same direction to a perfect fifth or octave

- unisons at any point in the exercise other than the first and last intervals

The Psychology of Counterpoint

The chapters on species counterpoint will not involve a specific style (classical, baroque, romantic, pop/rock, etc.). Instead, these exercises will set aside important musical elements like orchestration, melodic motives, formal structure, and even many elements of harmony and rhythm, in order to focus very specifically on a small set of fundamental musical problems. These fundamental problems are closely related to how some basic principles of auditory perception and cognition (i.e., how the brain perceives and conceptualizes sound) play out in Western musical structure.

For example, our brains tend to assume that sounds similar in pitch or timbre come from the same source. Our brains also listen for patterns, and when a new sound continues or completes a previously heard pattern, we typically assume that the new sound belongs together with those others. This is related to some of the most deep-seated, fundamental parts of our human experience, and even evolution. Hearing a regular pattern typically indicates a predictable (and safe) environment, while any change can signal danger and will tend to heighten our attention to the source. This system for directing attention (and adrenaline) where it is most likely to be needed has been essential to the survival of the human species. While listening to music in the 21st century does not (usually!) require us to listen out for animal predators, some part of that evolutionary experience is "hard-wired" into the psychology of human listening, and it has a role in what gives music its emotional effect—even in a safe environment.

For Western listeners, music that simply makes it easy for the brain to parse and process sound is boring—it calls for no heightened attention; it doesn’t increase our heart rate, make the hair on the back of our neck stand up, or give us a little jolt of dopamine. On the other hand, music that constantly activates our innate sense of danger is hardly pleasant for most listeners. That being the case, a balance between tension and relaxation, motion and rest, is fundamental to most of the music we will study.

The study of counterpoint helps us to engage several important musical “problems” in a strictly limited context, so that we can develop composition and analytical skills that can then be applied widely. Those problems arise as we seek to bring the following traits together:

- smooth, independent melodic lines

- tonal fusion (the preference for simultaneous notes to form a consonant unity)

- variety

- motion (towards a goal)

These traits are based in human perception and cognition, but they are often in conflict in specific musical moments and need to be balanced over the course of larger passages and complete works. Counterpoint will help us begin to practice working with that balance.

Finally, despite abstractions, it's still best to treat counterpoint exercises as miniature compositions and to perform them—vocally and instrumentally, and with a partner where possible—so that the ear, the fingers, the throat, and ultimately the mind can internalize the sound, sight, and feel of how musical lines work and combine.

- Huron, David. 2006. Sweet Anticipation: Music and the Psychology of Expectation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Cantus firmus A (.pdf, .mscx). Asks students to critique one cantus firmus and write their own.

- Cantus firmus B (.pdf, .mscx). Asks students to critique one cantus firmus and write their own.

- For the complete set of Fux exercises, see the Gradus ad Parnassum chapter.

Key Takeaways

- A beat is a pulse in music that regularly recurs.

- Simple meters are meters in which the beat divides into two, and then further subdivides into four.

- Duple meters have groupings of two beats, triple meters have groupings of three beats, and quadruple meters have groupings of four beats.

- There are different conducting patterns for duple, triple, and quadruple meters.

- A measure is equivalent to one group of beats (duple, triple, or quadruple). Measures are separated by bar lines.

- Time signatures in simple meters express two things: how many beats are contained in each measure (the top number), and the beat unit (the bottom number), which refers to the note value that is the beat.

- A beam visually connects notes together, grouping them by beat. Beaming changes in different time signatures.

- Notes below the middle line on a staff are up-stemmed, while notes above the middle line on a staff are down-stemmed. Flag direction works similarly.

In Rhythmic and Rest Values, we discussed the different rhythmic values of notes and rests. Musicians organize rhythmic values into various meters, which are—broadly speaking—formed as the result of recurrent patterns of accents in musical performances.

Terminology

Listen to the following performance by the contemporary musical group Postmodern Jukebox ( Example 1). They are performing a cover of the song "Wannabe" by the Spice Girls (originally released in 1996). Beginning at 0:11, it is easy to tap or clap along to this recording. What you are tapping along to is called a beat—a pulse in music that regularly recurs.

Example 1. A cover of "Wannabe" performed by Postmodern Jukebox; listen starting at 0:11.

Example 1 is in a simple meter: a meter in which the beat divides into two, and then further subdivides into four. You can feel this yourself by tapping your beat twice as fast; you might also think of this as dividing your beat into two smaller beats.

Different numbers of beats group into different meters. Duple meters contain beats that are grouped into twos, while Triple meters contain beats that are grouped into threes, and Quadruple meters contain beats that are grouped into fours.

Listening to Simple Meters

Let's listen to examples of simple duple, simple triple, and simple quadruple meters. A simple duple meter contains two beats, each of which divides into two (and further subdivides into four). "The Stars and Stripes Forever" (1896), written by John Philip Sousa, is in a simple duple meter.

Listen to Example 2, and tap along, feeling how the beats group into sets of two:

Example 2. "The Stars and Stripes Forever" played by the Dallas Winds.

A simple triple meter contains three beats, each of which divides into two (and further subdivides into four). Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's "Minuet in F major," K.2 (1774) is in a simple triple meter. Listen to Example 3, and tap along, feeling how the beats group into sets of three:

Example 3. Mozart's "Minuet in F major," played by Alan Huckleberry.

Finally, a simple quadruple meter contains four beats, each of which divides into two (and further subdivides into four). The song "Cake" (2017) by Flo Rida is in a simple quadruple meter. Listen to Example 4 starting at 0:45 and tap along, feeling how the beats group into sets of four:

Example 4. "Cake" by Flo Rida; listen starting at 0:45.

As you can hear and feel (by tapping along), musical compositions in a wide variety of styles are governed by meter. You might practice identifying the meters of some of your favorite songs or musical compositions as simple duple, simple triple, or simple quadruple; listening carefully and tapping along is the best way to do this. Note that simple quadruple meters feel similar to simple duple meters, since four beats can be divided into two groups of two beats. It may not always be immediately apparent if a work is in a simple duple or simple quadruple meter by listening alone.

Conducting Patterns

If you have ever sung in a choir or played an instrument in a band or orchestra, then you have likely had experience with a conductor. Conductors have many jobs. One of these jobs is to provide conducting patterns for the musicians in their choir, band, or orchestra. Conducting patterns serve two main purposes: first, they establish a tempo, and second, they establish a meter.

The three most common conducting patterns outline duple, triple, and quadruple meters. Duple meters are conducted with a downward/outward motion (step 1), followed by an upward motion (step 2), as seen in Example 5. Triple meters are conducted with a downward motion (step 1), an outward motion (step 2), and an upward motion (step 3), as seen in Example 6. Quadruple meters are conducted with a downward motion (step 1), an inward motion (step 2), an outward motion (step 3), and an upward motion (step 4), as seen in Example 7:

Beat 1 of each of these measures is considered a downbeat . A downbeat is conducted with a downward motion, and you may hear and feel that it has more "weight" or "heaviness" then the other beats. An upbeat is the last beat of any measure. Upbeats are conducted with an upward motion, and you may feel and hear that they are anticipatory in nature.

Example 8 shows a short video demonstrating these three conducting patterns:

Example 8. Dr. John Lopez (Texas A&M University, Kingsville) demonstrates duple, triple, and quadruple conducting patterns.

You can practice these conducting patterns while listening to Example 2 (duple), Example 3 (triple), and Example 4 (quadruple) above.

Time Signatures

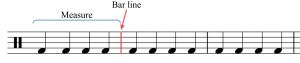

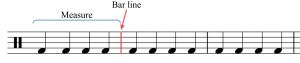

In Western musical notation, beat groupings (duple, triple, quadruple, etc.) are shown using bar lines, which separate music into measures (also called bars), as shown in Example 9. Each measure is equivalent to one beat grouping.

In simple meters, time signatures (also called meter signatures) express two things: 1) how many beats are contained in each measure, and 2) the beat unit (which note value gets the beat). Time signatures are expressed by two numbers, one above the other, placed after the clef (Example 10).

A time signature is not a fraction, though it may look like one; note that there is no line between the two numbers. In simple meters, the top number of a time signature represents the number of beats in each measure, while the bottom number represents the beat unit.

In simple meters, the top number is always 2, 3, or 4, corresponding to duple, triple, or quadruple beat patterns. The bottom number is usually one of the following:

- 2, which means the half note gets the beat.

- 4, which means the quarter note gets the beat.

- 8, which means the eighth note gets the beat.

You may also see the bottom number 16 (the sixteenth note gets the beat) or 1 (the whole note gets the beat) in simple meter time signatures.

There are two additional simple meter time signatures, which are 𝄴 (common time) and 𝄵 (cut time). Common time is the equivalent of [latex]\mathbf{^4_4}[/latex] (simple quadruple—four beats per measure), while cut time is the equivalent of [latex]\mathbf{^2_2}[/latex] (simple duple—two beats per measure).

Counting in Simple Meter

Counting rhythms aloud is important for musical performance; as a singer or instrumentalist, you must be able to perform rhythms that are written in Western musical notation. Conducting while counting rhythms is highly recommended and will help you to keep a steady tempo. Please note that your instructor may employ a different counting system. Open Music Theory privileges American traditional counting, but this is not the only method.

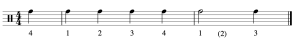

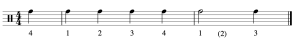

Example 11 shows a rhythm in a [latex]\mathbf{^4_4}[/latex] time signature, which is a simple quadruple meter. This time signature means that there are four beats per measure (the top 4) and that the quarter note gets the beat (the bottom 4).

- In each measure, each quarter note gets a count, expressed with Arabic numerals—"1, 2, 3, 4."

- When notes last longer than one beat (such as a half or whole note in this example), the count is held over multiple beats. Beats that are not counted out loud are written in parentheses.

- When the beat in a simple meter is divided into two, the divisions are counted aloud with the syllable “and,” which is usually notated with the plus sign (+). So, if the quarter note gets the beat, the second eighth note in each beat would be counted as “and.”

- Further subdivisions at the sixteenth-note level are counted as “e” (pronounced as a long vowel, as in the word “see”) and “a” (pronounced “uh”). At the thirty-second-note level, further subdivisions add the syllable “ta” in between each of the previous syllables.

Example 11. Rhythm in 4/4 time.

Simple duple meters have only two beats and simple triple meters have only three, but the subdivisions are counted the same way (Example 12).

Example 12. Simple duple meters have two beats per measure; simple triple meters have three.

Like with notes that last for two or more beats, beats that are not articulated because of rests, ties, and dots are also not counted out loud. These beats are usually written in parentheses, as shown in Example 13:

Example 13. Beats that are not counted out loud are put in parentheses.

When an example begins with a pickup note (anacrusis), your count will not begin on "1," as shown in Example 14. An anacrusis is counted as the last note(s) of an imaginary measure. When a work begins with an anacrusis, the last measure is usually shortened by the length of the anacrusis. This is demonstrated in Example 14: the anacrusis is one quarter note in length, so the last measure is only three beats long (i.e., it is missing one quarter note).

Counting with Beat Units of 2, 8, and 16

In simple meters with other beat units (shown in the bottom number of the time signature), the same counting patterns are used for the beats and subdivisions, but they correspond to different note values. Example 15 shows a rhythm with a [latex]\mathbf{^4_4}[/latex] time signature, followed by the same rhythms with different beat units. Each of these rhythms sounds the same and is counted the same. They are also all considered simple quadruple meters. The difference in each example is the bottom number of the time signature—which note gets the beat unit (quarter, half, eighth, or sixteenth).

Example 15. The same counted rhythm, as written in a meter with (a) a quarter-note beat, (b) a half-note beat, (c) an eighth-note beat, and (d) a sixteenth-note beat.

Beaming, Stems, Flags, and Multi-Measure Rests

Beams connect notes together by beat. As Example 16 shows, this means that beaming changes depending on the time signature. In the first measure, sixteenth notes are grouped into sets of four, because four sixteenth notes in a [latex]\mathbf{^4_4}[/latex] time signature are equivalent to one beat. In the second measure, however, sixteenth notes are grouped into sets of two, because one beat in a [latex]\mathbf{^4_8}[/latex] time signature is only equivalent to two sixteenth notes.

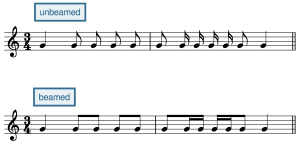

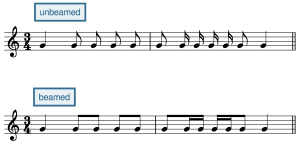

Example 16. Beaming in two different meters.

Note that in vocal music, beaming is sometimes only used to connect notes sung on the same syllable. If you are accustomed to music without beaming, you may need to pay special attention to beaming conventions until you have mastered them. In the top staff of Example 17, the eighth notes are not grouped with beams, making it difficult to see where beats 2 and 3 in the triple meter begin. The bottom staff shows that if we re-notate the rhythm so that the notes that fall within the same beat are grouped together with a beam, it makes the music much easier to read. Note that these two rhythms sound the same, even though they are beamed differently. The ability to group events according to a hierarchy is an important part of human perception, which is why beaming helps us visually parse notated musical rhythms—the metrical structure provides a hierarchy that we show using notational tools like beaming.

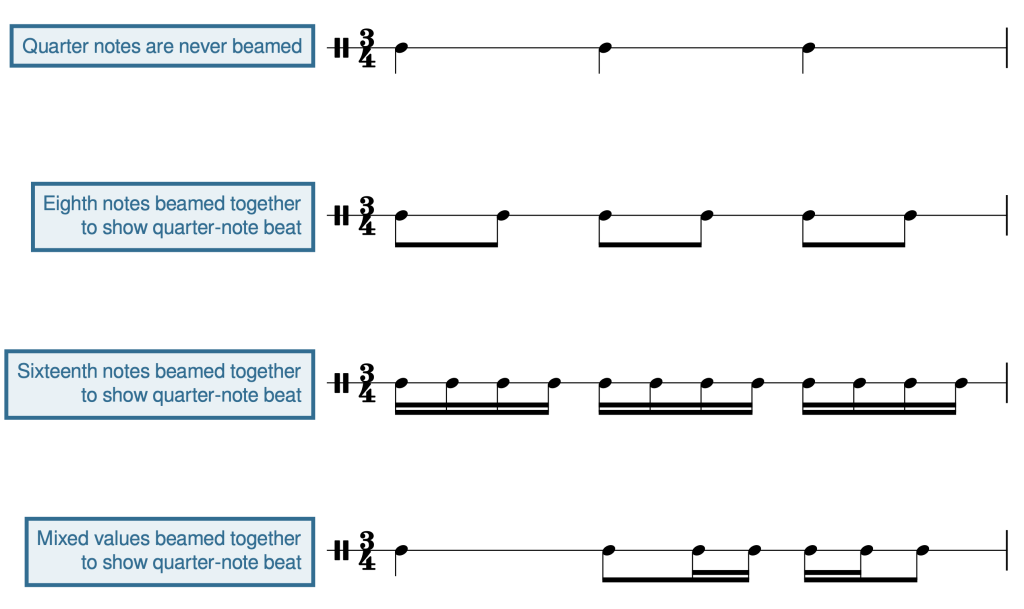

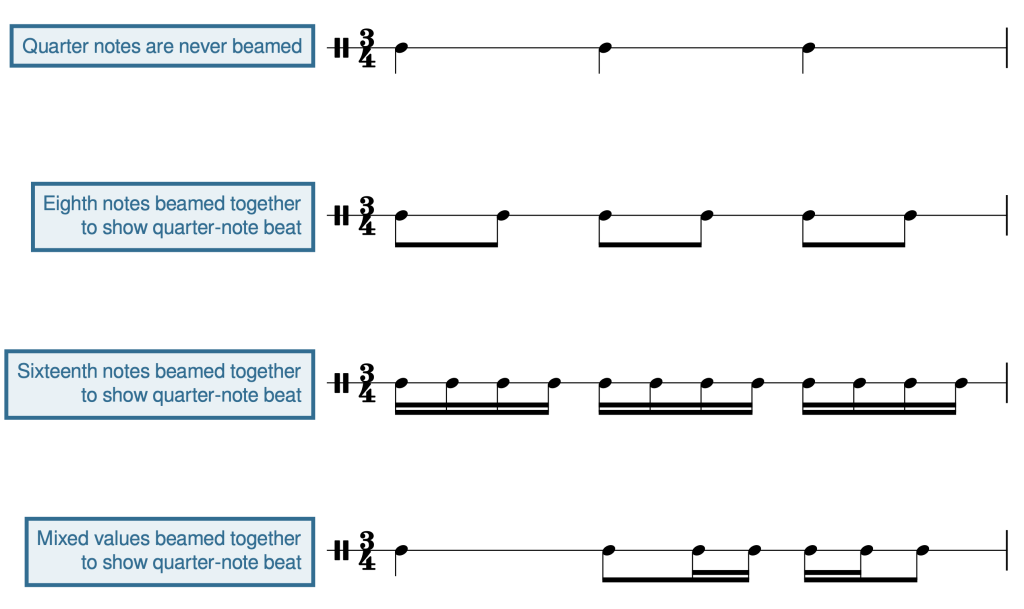

Example 18 shows several different note values beamed together to show the beat unit. The first line does not require beams because quarter notes are never beamed, but all subsequent lines do need beams to clarify beats.

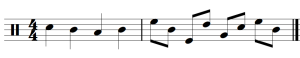

The second measure of Example 19 shows that when notes are grouped together with beams, the stem direction is determined by the note farthest from the middle line. On beat 1 of measure 2, this note is E5, which is above the middle line, so down-stems are used. Beat 2 uses up-stems because the note farthest from the middle line is the E4 below it.

Flagging is determined by stem direction (Example 20). Notes above the middle line receive a down-stem (on the left) and an inward-facing flag (facing right). Notes below the middle line receive an up-stem (on the right) and an outward-facing flag (facing left). Notes on the middle line can be flagged in either direction, usually depending on the contour of the musical line.

Partial beams can be used for mixed rhythmic groupings, as shown in Example 21. Sometimes these beaming conventions look strange to students who have had less experience with reading beamed music. If this is the case, you will want to pay special attention to how the notes in Example 21 are beamed.

Example 21. Partial beams are used for some mixed rhythmic groupings.

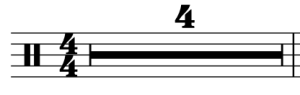

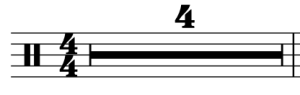

Rests that last for multiple full measures are sometimes notated as seen in Example 22. This example indicates that the musician is to rest for a duration of four full measures.

A Note on Ties

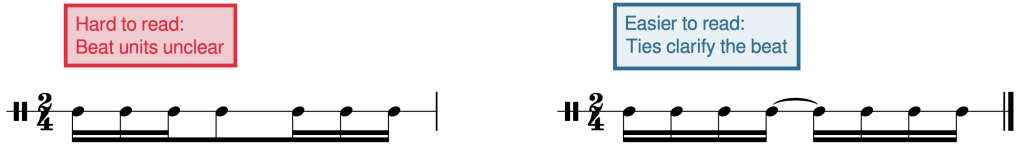

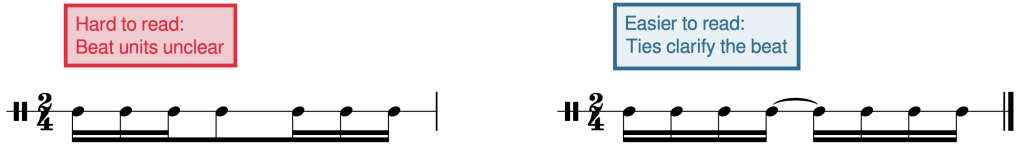

We have already encountered ties that can be used to extend a note over a measure line. But ties can also be used like beams to clarify the metrical structure within a measure. In the first measure of Example 23, beat 2 begins in the middle of the eighth note, making it difficult to see the metrical structure. Breaking the eighth note into two sixteenth notes connected by a tie, as shown in the second measure, clearly shows the beginning of beat 2.

- Simple Meter Tutorial (musictheory.net)

- Video Tutorial on Simple Meter, Beats, and Beaming (YouTube)

- Conducting Patterns (YouTube)

- Simple Meter Time Signatures (liveabout.com)

- Video Tutorial on Counting Simple Meters (One Minute Music Lessons)

- Simple Meter Counting (YouTube)

- Beaming Rules (Music Notes Now)

- Beaming Examples (Dr. Sebastian Anthony Birch)

- Time Signatures and Rhythms (.pdf)

- Terminology, Bar Lines, Fill-in-rhythms, Re-beaming (.pdf)

- Meters, Time Signatures, Re-beaming (website)

- Bar Lines, Time Signatures, Counting (.pdf)

- Time Signatures, Re-beaming, p. 4 (.pdf)

- Fill-in-rhythms (.pdf)

- Time Signatures (.pdf, .pdf)

- Bar Lines (.pdf, .pdf, .pdf)

The relative position of a note within a diatonic scale. Indicated with a number, 1–7, that indicates this position relative to the tonic of that scale.

Key Takeaways

- A beat is a pulse in music that regularly recurs.

- Simple meters are meters in which the beat divides into two, and then further subdivides into four.

- Duple meters have groupings of two beats, triple meters have groupings of three beats, and quadruple meters have groupings of four beats.

- There are different conducting patterns for duple, triple, and quadruple meters.

- A measure is equivalent to one group of beats (duple, triple, or quadruple). Measures are separated by bar lines.

- Time signatures in simple meters express two things: how many beats are contained in each measure (the top number), and the beat unit (the bottom number), which refers to the note value that is the beat.

- A beam visually connects notes together, grouping them by beat. Beaming changes in different time signatures.

- Notes below the middle line on a staff are up-stemmed, while notes above the middle line on a staff are down-stemmed. Flag direction works similarly.

In Rhythmic and Rest Values, we discussed the different rhythmic values of notes and rests. Musicians organize rhythmic values into various meters, which are—broadly speaking—formed as the result of recurrent patterns of accents in musical performances.

Terminology

Listen to the following performance by the contemporary musical group Postmodern Jukebox ( Example 1). They are performing a cover of the song "Wannabe" by the Spice Girls (originally released in 1996). Beginning at 0:11, it is easy to tap or clap along to this recording. What you are tapping along to is called a beat—a pulse in music that regularly recurs.

Example 1. A cover of "Wannabe" performed by Postmodern Jukebox; listen starting at 0:11.

Example 1 is in a simple meter: a meter in which the beat divides into two, and then further subdivides into four. You can feel this yourself by tapping your beat twice as fast; you might also think of this as dividing your beat into two smaller beats.

Different numbers of beats group into different meters. Duple meters contain beats that are grouped into twos, while Triple meters contain beats that are grouped into threes, and Quadruple meters contain beats that are grouped into fours.

Listening to Simple Meters

Let's listen to examples of simple duple, simple triple, and simple quadruple meters. A simple duple meter contains two beats, each of which divides into two (and further subdivides into four). "The Stars and Stripes Forever" (1896), written by John Philip Sousa, is in a simple duple meter.

Listen to Example 2, and tap along, feeling how the beats group into sets of two:

Example 2. "The Stars and Stripes Forever" played by the Dallas Winds.

A simple triple meter contains three beats, each of which divides into two (and further subdivides into four). Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's "Minuet in F major," K.2 (1774) is in a simple triple meter. Listen to Example 3, and tap along, feeling how the beats group into sets of three:

Example 3. Mozart's "Minuet in F major," played by Alan Huckleberry.

Finally, a simple quadruple meter contains four beats, each of which divides into two (and further subdivides into four). The song "Cake" (2017) by Flo Rida is in a simple quadruple meter. Listen to Example 4 starting at 0:45 and tap along, feeling how the beats group into sets of four:

Example 4. "Cake" by Flo Rida; listen starting at 0:45.

As you can hear and feel (by tapping along), musical compositions in a wide variety of styles are governed by meter. You might practice identifying the meters of some of your favorite songs or musical compositions as simple duple, simple triple, or simple quadruple; listening carefully and tapping along is the best way to do this. Note that simple quadruple meters feel similar to simple duple meters, since four beats can be divided into two groups of two beats. It may not always be immediately apparent if a work is in a simple duple or simple quadruple meter by listening alone.

Conducting Patterns

If you have ever sung in a choir or played an instrument in a band or orchestra, then you have likely had experience with a conductor. Conductors have many jobs. One of these jobs is to provide conducting patterns for the musicians in their choir, band, or orchestra. Conducting patterns serve two main purposes: first, they establish a tempo, and second, they establish a meter.

The three most common conducting patterns outline duple, triple, and quadruple meters. Duple meters are conducted with a downward/outward motion (step 1), followed by an upward motion (step 2), as seen in Example 5. Triple meters are conducted with a downward motion (step 1), an outward motion (step 2), and an upward motion (step 3), as seen in Example 6. Quadruple meters are conducted with a downward motion (step 1), an inward motion (step 2), an outward motion (step 3), and an upward motion (step 4), as seen in Example 7:

Beat 1 of each of these measures is considered a downbeat . A downbeat is conducted with a downward motion, and you may hear and feel that it has more "weight" or "heaviness" then the other beats. An upbeat is the last beat of any measure. Upbeats are conducted with an upward motion, and you may feel and hear that they are anticipatory in nature.

Example 8 shows a short video demonstrating these three conducting patterns:

Example 8. Dr. John Lopez (Texas A&M University, Kingsville) demonstrates duple, triple, and quadruple conducting patterns.

You can practice these conducting patterns while listening to Example 2 (duple), Example 3 (triple), and Example 4 (quadruple) above.

Time Signatures

In Western musical notation, beat groupings (duple, triple, quadruple, etc.) are shown using bar lines, which separate music into measures (also called bars), as shown in Example 9. Each measure is equivalent to one beat grouping.

In simple meters, time signatures (also called meter signatures) express two things: 1) how many beats are contained in each measure, and 2) the beat unit (which note value gets the beat). Time signatures are expressed by two numbers, one above the other, placed after the clef (Example 10).

A time signature is not a fraction, though it may look like one; note that there is no line between the two numbers. In simple meters, the top number of a time signature represents the number of beats in each measure, while the bottom number represents the beat unit.

In simple meters, the top number is always 2, 3, or 4, corresponding to duple, triple, or quadruple beat patterns. The bottom number is usually one of the following:

- 2, which means the half note gets the beat.

- 4, which means the quarter note gets the beat.

- 8, which means the eighth note gets the beat.

You may also see the bottom number 16 (the sixteenth note gets the beat) or 1 (the whole note gets the beat) in simple meter time signatures.

There are two additional simple meter time signatures, which are 𝄴 (common time) and 𝄵 (cut time). Common time is the equivalent of [latex]\mathbf{^4_4}[/latex] (simple quadruple—four beats per measure), while cut time is the equivalent of [latex]\mathbf{^2_2}[/latex] (simple duple—two beats per measure).

Counting in Simple Meter

Counting rhythms aloud is important for musical performance; as a singer or instrumentalist, you must be able to perform rhythms that are written in Western musical notation. Conducting while counting rhythms is highly recommended and will help you to keep a steady tempo. Please note that your instructor may employ a different counting system. Open Music Theory privileges American traditional counting, but this is not the only method.

Example 11 shows a rhythm in a [latex]\mathbf{^4_4}[/latex] time signature, which is a simple quadruple meter. This time signature means that there are four beats per measure (the top 4) and that the quarter note gets the beat (the bottom 4).

- In each measure, each quarter note gets a count, expressed with Arabic numerals—"1, 2, 3, 4."

- When notes last longer than one beat (such as a half or whole note in this example), the count is held over multiple beats. Beats that are not counted out loud are written in parentheses.

- When the beat in a simple meter is divided into two, the divisions are counted aloud with the syllable “and,” which is usually notated with the plus sign (+). So, if the quarter note gets the beat, the second eighth note in each beat would be counted as “and.”

- Further subdivisions at the sixteenth-note level are counted as “e” (pronounced as a long vowel, as in the word “see”) and “a” (pronounced “uh”). At the thirty-second-note level, further subdivisions add the syllable “ta” in between each of the previous syllables.

Example 11. Rhythm in 4/4 time.

Simple duple meters have only two beats and simple triple meters have only three, but the subdivisions are counted the same way (Example 12).

Example 12. Simple duple meters have two beats per measure; simple triple meters have three.

Like with notes that last for two or more beats, beats that are not articulated because of rests, ties, and dots are also not counted out loud. These beats are usually written in parentheses, as shown in Example 13:

Example 13. Beats that are not counted out loud are put in parentheses.

When an example begins with a pickup note (anacrusis), your count will not begin on "1," as shown in Example 14. An anacrusis is counted as the last note(s) of an imaginary measure. When a work begins with an anacrusis, the last measure is usually shortened by the length of the anacrusis. This is demonstrated in Example 14: the anacrusis is one quarter note in length, so the last measure is only three beats long (i.e., it is missing one quarter note).

Counting with Beat Units of 2, 8, and 16

In simple meters with other beat units (shown in the bottom number of the time signature), the same counting patterns are used for the beats and subdivisions, but they correspond to different note values. Example 15 shows a rhythm with a [latex]\mathbf{^4_4}[/latex] time signature, followed by the same rhythms with different beat units. Each of these rhythms sounds the same and is counted the same. They are also all considered simple quadruple meters. The difference in each example is the bottom number of the time signature—which note gets the beat unit (quarter, half, eighth, or sixteenth).

Example 15. The same counted rhythm, as written in a meter with (a) a quarter-note beat, (b) a half-note beat, (c) an eighth-note beat, and (d) a sixteenth-note beat.

Beaming, Stems, Flags, and Multi-Measure Rests

Beams connect notes together by beat. As Example 16 shows, this means that beaming changes depending on the time signature. In the first measure, sixteenth notes are grouped into sets of four, because four sixteenth notes in a [latex]\mathbf{^4_4}[/latex] time signature are equivalent to one beat. In the second measure, however, sixteenth notes are grouped into sets of two, because one beat in a [latex]\mathbf{^4_8}[/latex] time signature is only equivalent to two sixteenth notes.

Example 16. Beaming in two different meters.

Note that in vocal music, beaming is sometimes only used to connect notes sung on the same syllable. If you are accustomed to music without beaming, you may need to pay special attention to beaming conventions until you have mastered them. In the top staff of Example 17, the eighth notes are not grouped with beams, making it difficult to see where beats 2 and 3 in the triple meter begin. The bottom staff shows that if we re-notate the rhythm so that the notes that fall within the same beat are grouped together with a beam, it makes the music much easier to read. Note that these two rhythms sound the same, even though they are beamed differently. The ability to group events according to a hierarchy is an important part of human perception, which is why beaming helps us visually parse notated musical rhythms—the metrical structure provides a hierarchy that we show using notational tools like beaming.

Example 18 shows several different note values beamed together to show the beat unit. The first line does not require beams because quarter notes are never beamed, but all subsequent lines do need beams to clarify beats.

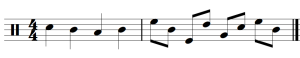

The second measure of Example 19 shows that when notes are grouped together with beams, the stem direction is determined by the note farthest from the middle line. On beat 1 of measure 2, this note is E5, which is above the middle line, so down-stems are used. Beat 2 uses up-stems because the note farthest from the middle line is the E4 below it.

Flagging is determined by stem direction (Example 20). Notes above the middle line receive a down-stem (on the left) and an inward-facing flag (facing right). Notes below the middle line receive an up-stem (on the right) and an outward-facing flag (facing left). Notes on the middle line can be flagged in either direction, usually depending on the contour of the musical line.

Partial beams can be used for mixed rhythmic groupings, as shown in Example 21. Sometimes these beaming conventions look strange to students who have had less experience with reading beamed music. If this is the case, you will want to pay special attention to how the notes in Example 21 are beamed.

Example 21. Partial beams are used for some mixed rhythmic groupings.

Rests that last for multiple full measures are sometimes notated as seen in Example 22. This example indicates that the musician is to rest for a duration of four full measures.

A Note on Ties

We have already encountered ties that can be used to extend a note over a measure line. But ties can also be used like beams to clarify the metrical structure within a measure. In the first measure of Example 23, beat 2 begins in the middle of the eighth note, making it difficult to see the metrical structure. Breaking the eighth note into two sixteenth notes connected by a tie, as shown in the second measure, clearly shows the beginning of beat 2.

- Simple Meter Tutorial (musictheory.net)

- Video Tutorial on Simple Meter, Beats, and Beaming (YouTube)

- Conducting Patterns (YouTube)

- Simple Meter Time Signatures (liveabout.com)

- Video Tutorial on Counting Simple Meters (One Minute Music Lessons)

- Simple Meter Counting (YouTube)

- Beaming Rules (Music Notes Now)

- Beaming Examples (Dr. Sebastian Anthony Birch)

- Time Signatures and Rhythms (.pdf)

- Terminology, Bar Lines, Fill-in-rhythms, Re-beaming (.pdf)

- Meters, Time Signatures, Re-beaming (website)

- Bar Lines, Time Signatures, Counting (.pdf)

- Time Signatures, Re-beaming, p. 4 (.pdf)

- Fill-in-rhythms (.pdf)

- Time Signatures (.pdf, .pdf)

- Bar Lines (.pdf, .pdf, .pdf)

The number of scale steps between notes of a collection or scale.