II. Counterpoint and Galant Schemas

25

Kris Shaffer and Mark Gotham

Key Takeaways

The third species of species counterpoint sees the counterpoint line move four times as fast as the cantus firmus. This introduces:

- a further metrical level (strong, weak, medium, weak)

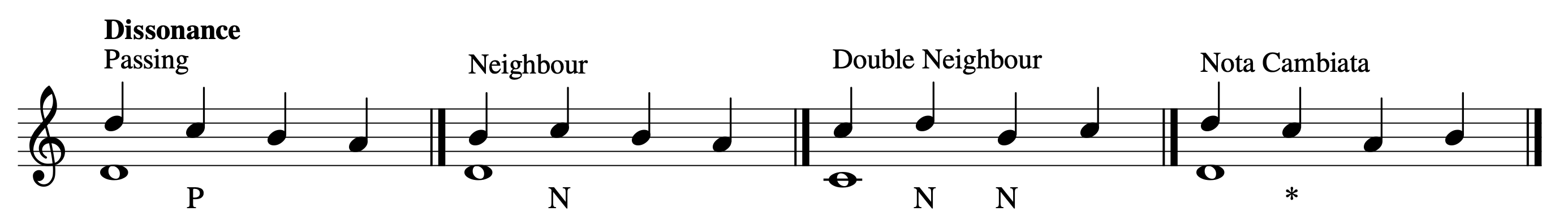

- a neighbor tone and other new dissonance types so that the total includes:

- The dissonant passing tone: fills in the space of a melodic third via stepwise motion.

- The dissonant neighbor tone: a step away from and back to the same consonant tone.

- The double neighbor: both the higher and lower neighbour tones together (e.g., C–D–B–C or C–B–D–C).

- The nota cambiata (changing tone) is special five-note figure that highly unusually includes a leap from a dissonance.

In third-species counterpoint, the counterpoint line moves in quarter notes against a cantus firmus in whole notes. This 4:1 rhythmic ratio creates a still greater differentiation between beats than in second species: strong beats (downbeats), moderately strong beats (the third quarter note of each bar), and weak beats (the second and fourth quarter notes of each bar). Third species also introduces the neighbor-tone dissonance and two related figures in which dissonances can participate in leaps.

Example 1 provides the examples of third-species counterpoint from Part I of Gradus ad Parnassum, annotated (as before) with the interval that the counterpoint line makes with the cantus firmus. For the complete examples from Gradus ad Parnassum as exercises, solutions, and annotations, see Gradus ad Parnassum Exercises.

https://musescore.com/user/32728834/scores/8488217/embed

Example 1. All third-species exercises from Gradus ad Parnassum.

The Counterpoint Line

As in first and second species, the counterpoint line should be singable and have a good shape, with a single climax that does not coincide with the climax of the cantus firmus, and primarily stepwise motion (with some small leaps and an occasional large leap for variety). Like second species, a third-species counterpoint should be dominated by stepwise motion, more so than in first species, because there are fewer sticky situations that would require a leap. If the counterpoint must leap, it is preferable to do so within the bar rather than across the bar line. Also like second species, there should usually be one or two secondary climaxes—notes lower than the overall climax that serve as “local” climaxes for portions of the line.

Beginning and Ending

Beginning a third-species counterpoint

Begin a third-species counterpoint above the cantus firmus with do ([latex]\hat1[/latex]) or sol ([latex]\hat5[/latex]). Begin a third-species counterpoint below the cantus firmus with do ([latex]\hat1[/latex]).

A third-species line can begin with four quarter notes in the first bar, or a quarter rest followed by three quarter notes. Regardless of rhythm, the first pitch in the counterpoint should follow the intervallic rules above.

Ending a third-species counterpoint

As in other species, end with a clausula vera. The final pitch of the counterpoint must always be do ([latex]\hat1[/latex]), and it must be a whole note.

The penultimate note of the counterpoint (the last quarter note of the penultimate bar) should be ti ([latex]\hat7[/latex]) if the cantus is re ([latex]\hat2[/latex]), and re ([latex]\hat2[/latex]) if the cantus is ti ([latex]\hat7[/latex]).

Strong Beats

Principles for strong beats (downbeats) are generally the same as in second species:

- Strong beats are always consonant, and not unisons.

- Prefer imperfect consonances (thirds and sixths) to perfect consonances (fifths and octaves).

Motion across bar lines (from beat 4 to downbeat) follows the same rules as first-species counterpoint.

Progressions from downbeat to downbeat follow principles of second-species counterpoint (except that direct fifths/octaves between successive downbeats are allowed). The following is a review of some of the most important principles from second species that apply in third species as well:

- No three consecutive bars can begin with the same perfect interval (two in a row are fine).

- No more than three bars in a row should begin with the same imperfect consonance.

- The pitches that begin consecutive downbeats must not make a dissonant melodic interval.

If a downbeat contains a perfect fifth, neither beat 3 nor 4 of the previous bar can be a fifth. If a downbeat contains an octave, neither beat 2, 3, nor 4 of the previous bar can be an octave. Like in second species, the negative effects of parallel fifths and octaves are not mitigated by the addition of a note or two.

Other Beats

Beats 2–4 should exhibit a mixture of consonant and dissonant intervals to promote variety. Among consonances, unisons are permitted on weak beats when necessary to make good counterpoint between the lines. Any dissonance must follow the pattern of the dissonant passing tone or the dissonant neighbor tone, explained below.

Consonance

The counterpoint can move in and out of consonant tones freely by step, as well as by leap from another consonance, with the following considerations:

- All melodic leaps, of course, must be melodic consonances.

- A large leap should be followed by a step in the opposite direction.

- Motion from the fourth beat into the following downbeat should follow the constraints above for motion into strong beats.

Dissonance

Dissonances in third species can occur on beat 2, 3, or 4, and should be preceded and followed by stepwise motion (with the exception of the double neighbor and the nota cambiata, explained below). This promotes smoothness, both by keeping the dissonances away from the strongest beat of the bar and by coupling them with the smoothest melodic motion. Dissonance handling in third-species counterpointcentered on the types illustrated in Example 2 and described below:

- The dissonant passing tone fills in the space of a melodic third via stepwise motion. The notes before and after the passing tone must be consonant with the cantus firmus. However, it is possible to have two dissonant passing tones in a row (P4–d5 or d5–P4). As long as these dissonances do not fall on downbeats and the counterpoint moves in stepwise motion in a single direction, there is no negative effect.

- The dissonant neighbor tone ornaments a consonant tone by stepping away and stepping back to the original consonance (6–7–6 over the cantus, for example). It is melodically identical to the consonant neighbor tone of second species, with the difference being the harmonic dissonance. Employing it on a weak beat (2 or 4) ensures the greatest smoothness.

- The double neighbor occurs when beats 1 and 4 in the counterpoint are the same tone, and beats 2 and 3 include the notes a step higher and a step lower than the original tone: for example, C–D–B–C or C–B–D–C. Both beats 2 and 3 are dissonant, but since both are embellishing the original tone by step, the leap between them does not significantly diminish the smoothness of the line. When using a double neighbor, the direction between beats 3 and 4 should be the same as between beat 4 and the following downbeat. That motion across the bar line should also be stepwise. This further maintains smoothness to temper the effect of the dissonances.

- The nota cambiata (changing tone) is a five-note figure that outlines a step progression from downbeat to downbeat. It follows one of two patterns shown in Example 3). For a nota cambiata to be effective, the first, third, and fifth notes must be consonant with the cantus. The second note will be dissonant and will leap to the third tone. However, like the double neighbor, the overall pattern minimizes the negative effect of the leap away from the dissonance. It is surrounded by stepwise motion, the overall progression is a single step, and the dissonant tone and the following downbeat are the same pitch.

https://musescore.com/user/32728834/scores/8487176/embed

Example 3. Two forms of nota cambiata. From downbeat to downbeat, the nota cambiata may fill in (a) a step down or (b) a step up.

- For the complete set of Fux exercises, see the Gradus ad Parnassum chapter.

Key Takeaways

In Western musical notation, pitches are designated by the first seven letters of the Latin alphabet: A, B, C, D, E, F, and G. After G these letter names repeat in a loop: A, B, C, D, E, F, G, A, B, C, D, E, F, G, A, B, C, etc. This loop of letter names exists because musicians and music theorists today accept what is called octave equivalence, or the assumption that pitches separated by an octave should have the same letter name. More information about this concept can be found in the next chapter, The Keyboard and the Grand Staff.

This assumption varies with milieu. For example, some ancient Greek music theorists did not accept octave equivalence. These theorists used more than seven letters of the Greek alphabet to name pitches.

Clefs and Ranges

The Notation of Notes, Clefs, and Ledger Lines chapter introduced four clefs: treble, bass, alto, and tenor. A clef indicates which pitches are assigned to the lines and spaces on a staff. In the next chapter, The Keyboard and the Grand Staff, we will see that having multiple clefs makes reading different ranges easier. The treble clef is typically used for higher voices and instruments, such as a flute, violin, trumpet, or soprano voice. The bass clef is usually utilized for lower voices and instruments, such as a bassoon, cello, trombone, or bass voice. The alto clef is primarily used for the viola, a mid-ranged instrument, while the tenor clef is sometimes employed in cello, bassoon, and trombone music (although the principal clef used for these instruments is the bass clef).

Each clef indicates how the lines and spaces of the staff correspond to pitch. Memorizing the patterns for each clef will help you read music written for different voices and instruments.

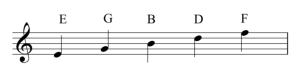

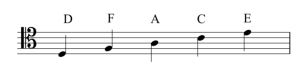

Reading Treble Clef

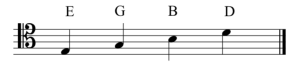

The treble clef is one of the most commonly used clefs today. Example 1 shows the letter names used for the lines of a staff when a treble clef is employed. One mnemonic device that may help you remember this order of letter names is "Every Good Bird Does Fly" (E, G, B, D, F). As seen in Example 1, the treble clef wraps around the G line (the second line from the bottom). For this reason, it is sometimes called the "G clef."

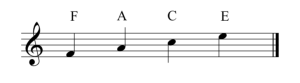

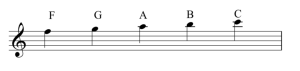

Example 2 shows the letter names used for the spaces of a staff with a treble clef. Remembering that these letter names spell the word "face" may make identifying these spaces easier.

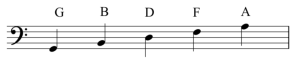

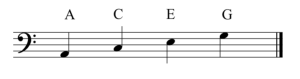

Reading Bass Clef

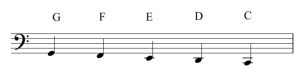

The other most commonly used clef today is the bass clef. Example 3 shows the letter names used for the lines of a staff when a bass clef is employed. A mnemonic device for this order of letter names is “Good Bikes Don’t Fall Apart” (G, B, D, F, A). The bass clef is sometimes called the “F clef”; as seen in Example 3, the dot of the bass clef begins on the F line (the second line from the top).

Example 4 shows the letter names used for the spaces of a staff with a bass clef. The mnemonic device "All Cows Eat Grass" (A, C, E, G) may make identifying these spaces easier.

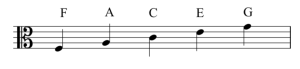

Reading Alto Clef

Example 5 shows the letter names used for the lines of the staff with the alto clef, which is less commonly used today. The mnemonic device “Fat Alley Cats Eat Garbage” (F, A, C, E, G) may help you remember this order of letter names. As seen in Example 5, the center of the alto clef is indented around the C line (the middle line). For this reason it is sometimes called a "C clef."

Example 6 shows the letter names used for the spaces of a staff with an alto clef, which can be remembered with the mnemonic device “Grand Boats Drift Flamboyantly” (G, B, D, F).

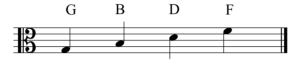

Reading Tenor Clef

The tenor clef, another less commonly used clef, is also sometimes called a “C clef,” but the center of the clef is indented around the second line from the top. Example 7 shows the letter names used for the lines of a staff when a tenor clef is employed, which can be remembered with the mnemonic device “Dodges, Fords, and Chevrolets Everywhere” (D, F, A, C, E):

Example 8 shows the letter names used for the spaces of a staff with a tenor clef. The mnemonic device "Elvis's Guitar Broke Down" (E, G, B, D) may make identifying these spaces easier.

Ledger Lines

When notes are too high or low to be written on a staff, small lines are drawn to extend the staff. You may recall from the previous chapter that these extra lines are called ledger lines. Ledger lines can be used to extend a staff with any clef. Example 9 shows ledger lines above a staff with a treble clef:

Notice that each space and line above the staff gets a letter name with ledger lines, as if the staff were simply continuing upwards. The same is true for ledger lines below a staff, as shown in Example 10:

Notice that each space and line below the staff gets a letter name with ledger lines, as if the staff were simply continuing downwards.

- The Staff, Clefs, and Ledger Lines (musictheory.net)

- Flashcards for Treble, Bass, Alto, and Tenor Clefs (Richman Music School)

- Printable Treble Clef Flash Cards (Samuel Stokes Music) (pages 3 to 5)

- Printable Bass Clef Flash Cards (Samuel Stokes Music) (pages 1 to 3)

- Printable Alto Clef Flash Cards (Samuel Stokes Music)

- Printable Tenor Clef Flash Cards (Samuel Stokes Music)

- Paced Game: Treble Clef (Tone Savvy)

- Paced Game: Bass Clef (Tone Savvy)

- Paced Game: Alto Clef (Tone Savvy)

- Paced Game: Tenor Clef (Tone Savvy)

Easy

Medium

- Worksheets in Treble Clef (.pdf)

- Treble Clef with Ledger Lines (.pdf)

- Worksheets in Bass Clef (.pdf, .pdf)

- Bass Clef with Ledger Lines (.pdf)

- Worksheets in Alto Clef (.pdf, .pdf)

- Worksheets in Tenor Clef (.pdf)

Advanced

- All Clefs (.pdf)

A type of motion where a chord tone moves by step to another tone, then moves back to the original chord tone. For example, C–D–C above a C major chord would be an example of neighboring motion, in which D can be described as a neighbor tone. Entire harmonies may be said to be neighboring when embellishing another harmony, when the voice-leading between the two chords involves only neighboring and common-tone motion (as in the common-tone diminished seventh chord).

Beat 1 of a measure, which is conducted with a downward motion.

.front-matter h6 {

font-size: 1.25em;

}

.textbox--sidebar {

float: right;

margin: 1em 0 1em 1em;

max-width: 45%;

}

.textbox.textbox--key-takeaways .textbox__header p {

font: sans-serif !important;

font-weight: bold;

text-transform: uppercase;

font-style: normal;

font-size: larger;

}

a {

text-decoration: none;

color: blue;

text-transform: uppercase;

}