IV. Diatonic Harmony, Tonicization, and Modulation

52

John Peterson

Key Takeaways

This chapter introduces three additional [latex]^6_4[/latex] chords beyond cadential [latex]^6_4[/latex].

- Passing (pass.) [latex]^6_4[/latex] involves a passing tone in the bass that has been harmonized by a [latex]^6_4[/latex] chord. It typically prolongs tonic or predominant harmonies, and it always occurs between two chords of the same function.

- Neighbor (n.) [latex]^6_4[/latex] involves a static bass above which two of the upper voices perform upper neighbor motion. It typically prolongs tonic or dominant harmonies, and the chords on both sides of it are always in root position.

- Arpeggiating (arp.) [latex]^6_4[/latex] involves a bass that arpeggiates through the fifth of the chord while the upper voices sustain the chord in some way. It may prolong any harmony, and we don’t typically bother recognizing it in analysis.

The table in Example 6 below summarizes the characteristics of each of the three types of [latex]^6_4[/latex] that we advocate labeling in analysis.

So far, we’ve seen that the tonic (T) area is most commonly prolonged using dominant-function chords, especially inverted [latex]\mathrm{V^7}[/latex]s. In this chapter, we look at some additional, less common ways to prolong not only tonic chords, but also dominant and predominant chords. Earlier, we saw how [latex]^6_4[/latex] chords are treated in special ways because they contain a dissonance with the bass (the fourth). We’ve already learned about [latex]\mathrm{cad.^6_4}[/latex]; here, we turn to the three other ways [latex]^6_4[/latex] chords can be used: passing [latex]^6_4[/latex], neighboring [latex]^6_4[/latex], and arpeggiating [latex]^6_4[/latex]. Note that in analysis, whenever you encounter a [latex]^6_4[/latex] chord, you should stop and identify which kind it is (cadential, passing, neighboring, or arpeggiating) because the kind of [latex]^6_4[/latex] determines the label. For [latex]^6_4[/latex] chords, the Roman numeral by itself isn’t a sufficient label—the type also needs to be included.

Passing [latex]^6_4[/latex]

The passing (pass.) [latex]^6_4[/latex] is a [latex]^6_4[/latex] chord built on a passing tone in the bass (Example 1). It’s most commonly found prolonging tonic or predominant harmonies. Importantly, the chords on both sides of the [latex]\mathrm{pass.^6_4}[/latex] are always the same function (e.g., [latex]\mathrm{IV^6-pass.^6_4-ii^6}[/latex]), not of different function (e.g., [latex]\mathrm{IV^6-pass.^6_4-I}[/latex]).

https://musescore.com/user/32728834/scores/6250658/embed

Example 1. [latex]\mathrm{pass.^6_4}[/latex] in Beethoven, Piano Sonata Op. 14, no. 1, I, mm. 50–57 (1:28-1:42).

Example 2a demonstrates the steps for writing [latex]\mathrm{pass.^6_4}[/latex] to expand tonic, and Examples 2b and 2c show several ways [latex]\mathrm{pass.^6_4}[/latex] can prolong the predominant area. Note that each of these progressions can also work backward (e.g., [latex]\mathrm{I^6-pass.^6_4-I}[/latex] also works).

To write with pass[latex]^6_4[/latex]:

- Write the entire bass. You should have three notes in stepwise motion where the first and last notes belong to the same functional area (T or PD). The middle note will be your passing tone.

- Spell the pass.[latex]\mathbf{^6_4}[/latex]. Just like with [latex]\mathrm{cad.^6_4}[/latex], to spell [latex]\mathrm{pass.^6_4}[/latex], determine what notes are a fourth and sixth above the bass. One voice will double the bass, just like in [latex]\mathrm{cad.^6_4}[/latex].

- Write the entire soprano. The soprano should be a line that moves by step, not the static line.

- Fill in inner voices, making them move as little as possible.

https://musescore.com/user/32728834/scores/6250667/embed

Example 2. Writing with pass.[latex]\mathit{^6_4}[/latex].

Neighbor [latex]^6_4[/latex]

The neighbor (n.) [latex]^6_4[/latex] consists of a static bass over top of which two voices have upper-neighbor motion (Example 3). Sometimes [latex]\mathrm{n.^6_4}[/latex] is called pedal [latex]^6_4[/latex], a name that reflects the static pedal in the bass. It’s most commonly found prolonging I or V. Example 4a demonstrates the steps for writing [latex]\mathrm{n.^6_4}[/latex] to prolong tonic, and Example 4b shows the voice leading to prolong V.

https://musescore.com/user/32728834/scores/6250673/embed

Example 3. Neighbor and arpeggiating [latex]\mathit{^6_4}[/latex] in Josephine Lang, “Dem Königs-Sohn.”

To write with [latex]\mathrm{n.^6_4}[/latex]:

- Write the entire bass. The bass will be three of the same note, typically do–do–do or sol–sol–sol ([latex]\hat1-\hat1-\hat1[/latex] or [latex]\hat5-\hat5-\hat5[/latex])

- Spell n.[latex]\mathbf{^6_4}[/latex]. The [latex]\mathrm{n.^6_4}[/latex] will be over the middle bass note. As with [latex]\mathrm{cad.}[/latex] and [latex]\mathrm{pass.^6_4}[/latex], determine a sixth and fourth above the middle bass note. One voice will double the bass.

- Write the entire soprano. For the soprano, choose either an upper-neighbor line or the static line. Unlike with [latex]\mathrm{cad.}[/latex] or [latex]\mathrm{pass.^6_4}[/latex], [latex]\mathrm{n.^6_4}[/latex] will more frequently have a static line in the soprano.

- Fill in the inner voices, making them move as little as possible.

https://musescore.com/user/32728834/scores/6250679/embed

Example 4. Writing with [latex]\mathit{n.^6_4}[/latex].

Arpeggiating [latex]^6_4[/latex]

Arpeggiating (arp.) [latex]^6_4[/latex] is typically created when the bass leaps to the fifth of a chord while the upper voices sustain the chord. It’s commonly found in, for example, ending bass arpeggiations (Example 3) or waltz-style accompaniments (Example 5). Unlike the other types, [latex]\mathrm{arp.^6_4}[/latex] typically doesn’t need to be labeled in analysis. Example 5 identifies it using figures, but it’s not necessary to do so—each measure could simply be labeled as I.

https://musescore.com/user/32728834/scores/6250685/embed

Example 5. Arpeggiating [latex]\mathit{^6_4}[/latex] in Sophie de Auguste Weyrauch, Six Danses No. 3.

Summary: 6/4 chord types

The table in Example 6 summarizes the characteristics of the three [latex]^6_4[/latex] chord types that should be labeled in analysis. When you come across a [latex]^6_4[/latex] chord in analysis, remember to stop and ask yourself what type it is (passing, neighboring, or cadential) and label it appropriately.

[table “45” not found /]

Example 6. Summary of [latex]\mathit{^6_4}[/latex] chord types.

- [latex]^6_4[/latex] chords as forms of prolongation (.pdf, .docx). Asks students to review previous concepts, write from Roman numerals, write from figures, and analyze excerpts.

Key Takeaways

In Western musical notation, pitches are designated by the first seven letters of the Latin alphabet: A, B, C, D, E, F, and G. After G these letter names repeat in a loop: A, B, C, D, E, F, G, A, B, C, D, E, F, G, A, B, C, etc. This loop of letter names exists because musicians and music theorists today accept what is called octave equivalence, or the assumption that pitches separated by an octave should have the same letter name. More information about this concept can be found in the next chapter, The Keyboard and the Grand Staff.

This assumption varies with milieu. For example, some ancient Greek music theorists did not accept octave equivalence. These theorists used more than seven letters of the Greek alphabet to name pitches.

Clefs and Ranges

The Notation of Notes, Clefs, and Ledger Lines chapter introduced four clefs: treble, bass, alto, and tenor. A clef indicates which pitches are assigned to the lines and spaces on a staff. In the next chapter, The Keyboard and the Grand Staff, we will see that having multiple clefs makes reading different ranges easier. The treble clef is typically used for higher voices and instruments, such as a flute, violin, trumpet, or soprano voice. The bass clef is usually utilized for lower voices and instruments, such as a bassoon, cello, trombone, or bass voice. The alto clef is primarily used for the viola, a mid-ranged instrument, while the tenor clef is sometimes employed in cello, bassoon, and trombone music (although the principal clef used for these instruments is the bass clef).

Each clef indicates how the lines and spaces of the staff correspond to pitch. Memorizing the patterns for each clef will help you read music written for different voices and instruments.

Reading Treble Clef

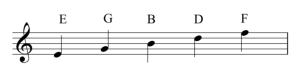

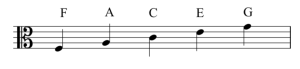

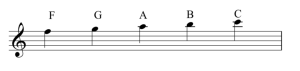

The treble clef is one of the most commonly used clefs today. Example 1 shows the letter names used for the lines of a staff when a treble clef is employed. One mnemonic device that may help you remember this order of letter names is "Every Good Bird Does Fly" (E, G, B, D, F). As seen in Example 1, the treble clef wraps around the G line (the second line from the bottom). For this reason, it is sometimes called the "G clef."

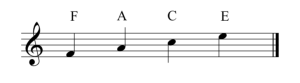

Example 2 shows the letter names used for the spaces of a staff with a treble clef. Remembering that these letter names spell the word "face" may make identifying these spaces easier.

Reading Bass Clef

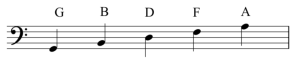

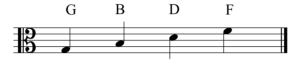

The other most commonly used clef today is the bass clef. Example 3 shows the letter names used for the lines of a staff when a bass clef is employed. A mnemonic device for this order of letter names is “Good Bikes Don’t Fall Apart” (G, B, D, F, A). The bass clef is sometimes called the “F clef”; as seen in Example 3, the dot of the bass clef begins on the F line (the second line from the top).

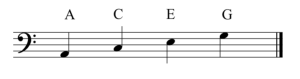

Example 4 shows the letter names used for the spaces of a staff with a bass clef. The mnemonic device "All Cows Eat Grass" (A, C, E, G) may make identifying these spaces easier.

Reading Alto Clef

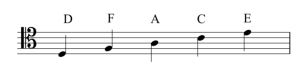

Example 5 shows the letter names used for the lines of the staff with the alto clef, which is less commonly used today. The mnemonic device “Fat Alley Cats Eat Garbage” (F, A, C, E, G) may help you remember this order of letter names. As seen in Example 5, the center of the alto clef is indented around the C line (the middle line). For this reason it is sometimes called a "C clef."

Example 6 shows the letter names used for the spaces of a staff with an alto clef, which can be remembered with the mnemonic device “Grand Boats Drift Flamboyantly” (G, B, D, F).

Reading Tenor Clef

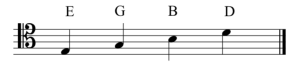

The tenor clef, another less commonly used clef, is also sometimes called a “C clef,” but the center of the clef is indented around the second line from the top. Example 7 shows the letter names used for the lines of a staff when a tenor clef is employed, which can be remembered with the mnemonic device “Dodges, Fords, and Chevrolets Everywhere” (D, F, A, C, E):

Example 8 shows the letter names used for the spaces of a staff with a tenor clef. The mnemonic device "Elvis's Guitar Broke Down" (E, G, B, D) may make identifying these spaces easier.

Ledger Lines

When notes are too high or low to be written on a staff, small lines are drawn to extend the staff. You may recall from the previous chapter that these extra lines are called ledger lines. Ledger lines can be used to extend a staff with any clef. Example 9 shows ledger lines above a staff with a treble clef:

Notice that each space and line above the staff gets a letter name with ledger lines, as if the staff were simply continuing upwards. The same is true for ledger lines below a staff, as shown in Example 10:

Notice that each space and line below the staff gets a letter name with ledger lines, as if the staff were simply continuing downwards.

- The Staff, Clefs, and Ledger Lines (musictheory.net)

- Flashcards for Treble, Bass, Alto, and Tenor Clefs (Richman Music School)

- Printable Treble Clef Flash Cards (Samuel Stokes Music) (pages 3 to 5)

- Printable Bass Clef Flash Cards (Samuel Stokes Music) (pages 1 to 3)

- Printable Alto Clef Flash Cards (Samuel Stokes Music)

- Printable Tenor Clef Flash Cards (Samuel Stokes Music)

- Paced Game: Treble Clef (Tone Savvy)

- Paced Game: Bass Clef (Tone Savvy)

- Paced Game: Alto Clef (Tone Savvy)

- Paced Game: Tenor Clef (Tone Savvy)

Easy

Medium

- Worksheets in Treble Clef (.pdf)

- Treble Clef with Ledger Lines (.pdf)

- Worksheets in Bass Clef (.pdf, .pdf)

- Bass Clef with Ledger Lines (.pdf)

- Worksheets in Alto Clef (.pdf, .pdf)

- Worksheets in Tenor Clef (.pdf)

Advanced

- All Clefs (.pdf)

A type of motion where a chord tone moves by step to another tone, then moves back to the original chord tone. For example, C–D–C above a C major chord would be an example of neighboring motion, in which D can be described as a neighbor tone. Entire harmonies may be said to be neighboring when embellishing another harmony, when the voice-leading between the two chords involves only neighboring and common-tone motion (as in the common-tone diminished seventh chord).

.front-matter h6 {

font-size: 1.25em;

}

.textbox--sidebar {

float: right;

margin: 1em 0 1em 1em;

max-width: 45%;

}

.textbox.textbox--key-takeaways .textbox__header p {

font: sans-serif !important;

font-weight: bold;

text-transform: uppercase;

font-style: normal;

font-size: larger;

}

.button {

background: gray;

text-decoration: none;

}