II. Counterpoint and Galant Schemas

29

Mark Gotham

Key Takeaways

- The 16th-century contrapuntal style is related—but not identical—to the principles outlined in species counterpoint.

- This chapter sets out some key principles and practice exercises especially for imitation.

The 16th-century contrapuntal style has historically enjoyed a prominent position in the teaching of music theory. "Pastiche" or "counterfactual" composition of 16th-century imitative choral polyphony (especially in the style of Palestrina) has frequently appeared in curricula and is sometimes conflated with the later, 18th-century notion of species counterpoint which we met in the previous chapters. This chapter sets out some rules of thumb to bear in mind when completing style-composition exercises based on this repertoire where you are given a partial score to complete. At the end, you'll find a couple of example exercises in this format.

Imitation

Imitation involves two or more parts entering separately with the same melody, or versions of the same melody. This is a common practice in 16th-century contrapuntal music, particularly for beginning whole movements and large sections in those movements (with the introduction of a new line of text, for instance). You might think of it as a precursor to the later fugue (which we'll return to in the High Baroque Fugal Exposition chapter).

Here is an example from Vicente Lusitano’s “Ave spes nostra” from the

In this opening passage, a “point of imitation” setting the text “Ave spes nostra” appears in all five voices. The imitation is exact, give or take small changes. The first voice to enter starts on F and descends to C, then it repeats the text a second time, now starting on C and descending to F with a similar melody, adding one more note at the end. Other parts imitate either this pattern (F–C then C–F) or this pair the other way round (C–F, then F–C).

The end of this example sees the start of a second imitative point setting the next line “Dei genitrix ... ”. This new figure has a “turn”-like shape: original note, note above, note below, original note (C-D-Bb-C). What follows is a sectnmio based on that second point. As is common in this style, the two phrase overlap (i.e., the new phrase begins before the end of the previous one) and the imitation for this second point is treated more freely than the first. You can even see a couple of subtle rhythmic changes to the first point in this last bar shown where this overlap takes place.

When completing an exercise involving imitation, let the existing material be your guide and consider the following guidelines:

- Identify (potential) points of imitation: In any given part, look for changes of text (often preceded by a comma or rest), and particularly any repetition of text with the same music.

- Pitch interval: The interval between imitative parts at the start of a section or movement is usually a perfect consonance. That said, others are eminently possible, especially later in the movement. Note that we are talking about the primary corresponding interval between the parts and not necessarily the very first pitch. We sometimes see examples of the tonal answer typical of the later high Baroque fugue, discussed in the next chapter.

- Meter: Imitate at metrically comparable positions (strong beat → strong beat; weak beat → weak beat).

- When working out what imitative relationships will work, try out all options in both directions. As the section governed by one imitative point often overlaps with the next, imitative entries around that section change may come from other point.

- Make sure there is meaningful overlap between consecutively entering imitative parts. To achieve that, shorter points of imitation may require correspondingly shorter intervals between entering parts.

- Consider how much of the point to imitate. Longer melodies eventually go from being a point to imitate exactly, to free counterpoint. Where does that change occur in this case?

- Consider how closely to imitate the point. Try to preserve at least the rhythm and the distinctive intervals/contour/shape of the point’s opening.

- Remember that phrases and sections can overlap, even at strong cadences.

Melody

- Contrary motion predominates between parts (partly to maintain independence of lines). Avoid too much parallel writing even of permitted intervals (but note the exceptional case of the "fauxbourdon," which is an extended passage of parallel [latex]^6_3[/latex] triads).

- Conjunct motion predominates within parts.

- Approach the final by step (in most parts).

- Raise the leading note when approaching the final from below (in most modal contexts, though not Phrygian).

- Melodic intervals:

- Seconds, thirds, fourths, fifths, and octaves are all permitted;

- The status of sixths is more complex. Rising minor sixths are used fairly freely (814 times in the Palestrina masses), rising major sixths are rarer (54 times), and descending sixths are extremely rare (7 descending minor, 1 single case of descending major).

- Sevenths and tritones are avoided. Do not even outline these intervals with successive leaps or by the boundaries (high and low points) of a melodic gesture.

- Successive leaps in the same direction are generally avoided. If you do have such successive leaps, then position the larger leap lower (first when rising, second when descending).

- Large leaps are to be followed (and often preceded) by motion in the opposite direction. This is connected to both the idea of gap-fill and regression to the middle of the tessitura.

- Avoid outlining triads as if you were arpeggiating chords.

- Contour: The arch shape is common for melodies (what goes up must come down!).

- Range per part: A common recommendation is to place each voice within an octave, corresponding to either the authentic or plagal ranges of the piece's mode. But in practice, parts more often span a slightly wider range of 14 semitones. Extremely few parts exceed the twelfth (octave plus fifth), so take that as a maximum.

- Common melodic devices:

- Suspensions: Suspended notes are to be "prepared" as a consonance on a weak metrical tied to a dissonance (on a strong position) and resolved by moving the suspended dissonant part down a step. For 7–6 and 4–3 suspensions, this involves dissonance in the upper voice; for 2–3 suspension, the dissonance is in the lower voice (as an inversion of 7–6). This is explained further in the chapter on fourth-species counterpoint.

- While not a suspension, the oblique motion from fifth to sixth is also common.

- Decorations at the end of a phrase are more common than at the beginning.

Rhythm and Meter

- The original notation for this repertoire lacks bar lines, but metrical thinking is abundantly clear. While modern editions will usually put bar lines in explicitly, remember that these are editorial interventions, not original. Editors may also change the tactus-level note values to be shorter than what was originally notated (from half to quarter notes, for instance). With those caveats borne in mind, the editorial intervention can be helpful—barlines are helpful for rehearsal and for conducting, and some performers may feel more comfortable reading in shorter note values. Editorial choices may also offer subtler hints, such as the use of "longer" meters ([latex]\mathbf{^2_2}[/latex] in place of [latex]\mathbf{^4_4}[/latex]) to hint at the possibility of thinking in terms of longer beat, and thus the possibility of longer dissonances, for instance.

- Melodic lines frequently start (and often end) with slower rhythmic movement.

- Half-tactus (quarter-note) movement should begin on weak metrical positions—on an unaccented beat (2 or 4), or between beats (as part of a dotted rhythm).

- Ties connect long notes to shorter ones (not vice versa).

- In the (relatively rare) cases of triple meter, rhythms generally divide into 2+1 rather than 1+2 (as in many styles).

Text Setting

- Clarity of music and text was held in high regard by many composers of this time.[2]

- Meter: The above caveats notwithstanding, match textual and musical meters by placing strong syllables on "strong beats." Systematic exceptions follow the conventions outlined above including syncopations, suspensions, and "metrical dissonance" (use of a consistent meter in one part that is contrary to that prevailing in other parts (usually the one notated in modern editions).

- Musical phrases follow the text.

- Typically use at least one beat (half note) for each syllable.

- Exceptions include dotted rhythms, where the shorter (quarter) note frequently receives its own syllable. This may be thought of as a modification of a "straight" rhythm, which meets the "one per beat" guideline.

- Syllable changes immediately after sub-tactus (quarter-note) motion are rare.

Texture

- The appropriate texture is usually clear from the given parts in these exercises.

- To generalize rather crudely, broad conventions for textures in Mass settings are as follows (where I = usually imitative; H = may be [more] homophonic):

- Kyrie (I).

- Gloria (H). The "qui tollis" frequently exists as a separate section.

- Credo (H). Especially often homophonic at important moments. "Crucifixus" separable.

- Sanctus (I). Hosanna (H).

- Benedictus (I). Often for fewer voices. (Second Hosanna usually a repeat of the first.)

- Agnus Dei (I). There may be a second or third Agnus, often with more parts and canons.

- The Magnificat tends to be a freer genre that is more flexible with the points of imitations.

Harmony

Composers of this era did not think in terms of chords, Roman numerals, inversions, and so on the way that we typically do today. Instead, they were principally concerned with intervallic relationships among parts. With this in mind, following are some guidelines for the vertical combination of parts in this style.

- Parallel fifths and parallel octaves: Avoid, as in later idioms. However, unlike in later idioms, those involving diminished fifths must also be avoided.

- Direct fifths or octaves:

- Avoid in principle (some rationalize this on the basis that they imply parallels that would present if the intervening passing notes were added).

- More common at cadences and/or when mitigated by strong contrary motion in one or more other parts.

- Diminished triad:

- Used not infrequently in Palestrina’s music, mostly in first inversion.

- Useful especially as a solution for cadences in multi-part music with [latex]\hat2-\hat1[/latex] motion in the bass, for instance.

- Resolve according to standard voice-leading: re–do, ti–do, fa–mi [latex](\hat2-\hat1,\ \hat7-\hat8,\ \hat4-\hat3)[/latex].

- Dissonance: types and treatment:

- Suspensions: preparation (weak beat) – suspension (strong) – resolution (weak).

- "Inessential" dissonances: passing tones, neighbor tones at the sub-tactus (quarter-note) level.

- Nota cambiata, "changed note": generally do–ti–sol–la [latex](\hat8-\hat7-\hat5-\hat6)[/latex]. The only case of a dissonance left by leap.

- Final chord: Bare fifth or major triad (picardy third).

- The raised ("Picardy") third "originated c. 1500 when for the first time, the third was admitted in the final chord of a piece … in the second half of the sixteenth century this practice became fairly common" (Apel 1969, 677).

- By Palestrina, major triads are the most common kind of final chord (accounting for around 85% of cases in the Palestrina masses).

- Apel, Willi. "Picardy Third." 1969. Harvard Dictionary of Music. 2nd ed. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

In addition to well-known libraries like IMSLP, there are some interesting projects dedicated specifically to Renaissance music.

- Perhaps most notable and relevant is Citations: The Renaissance Imitation Mass Project (CRIM), where you can explore a wide range of relevant repertoire in attractive, modern editions, along with related information.

- For a similar curatorial approach to a slightly earlier repertoire, you may wish to explore the Josquin Research Project (JRP)

- Imitative writing in the 16th-century contrapuntal style. These exercises provide at least one complete part for reference, and one part with missing passages to complete in a suitable style. Original note values are used, with modern time signatures for those values ([latex]\mathbf{^4_2}[/latex]), some editorial accidentals (ficta), and only G and F clefs.

- IMSLP has this numbered simply as No. “10”, but if consulting the source, note that the parts are numbered as follows in book order: Supranus 24 (“XXIIII”, name and numbering sic), Altus 26 (“XXVI”), Tenor 25 (XXV”), Bassus 23 (XXIII, sic even though the source index page says 22), and Quinta Pars 25 (XXV), remaining parts not applicable. The transcription is in modern notation, but preserves original pitch and note values. ↵

- This is said to be especially true of Palestrina, and further said to have appeased the Council of Trent in its review of recent developments in music. ↵

At the end of each chapter, you may find Assignments linked for that chapter. Those same assignments are also gathered here in a single table for convenient browsing.

Use arrows in the cells on the header row to sort the table alphabetically. Use the "Search" function to filter by the words in your search.

Last updated: September 18, 2023 4:09 pm

| Book order | Part | Chapter | Assignments |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | I. Fundamentals | Introduction to Western Musical Notation |

|

| 2 | I. Fundamentals | Notation of Notes, Clefs, and Ledger Lines |

|

| 3 | I. Fundamentals | Reading Clefs |

|

| 4 | I. Fundamentals | The Keyboard and the Grand Staff |

|

| 5 | I. Fundamentals | Half Steps, Whole Steps, and Accidentals |

|

| 6 | I. Fundamentals | American Standard Pitch Notation (ASPN) |

|

| 7 | I. Fundamentals | Other Aspects of Notation |

|

| 8 | I. Fundamentals | Notating Rhythm |

|

| 9 | I. Fundamentals | Simple Meter and Time Signatures |

|

| 10 | I. Fundamentals | Compound Meter and Time Signatures |

|

| 11 | I. Fundamentals | Other Rhythmic Essentials |

|

| 12 | I. Fundamentals | Major Scales, Scale Degrees, and Key Signatures |

|

| 13 | I. Fundamentals | Minor Scales, Scale Degrees, and Key Signatures |

|

| 14 | I. Fundamentals | Introduction to Diatonic Modes and the Chromatic “Scale” |

|

| 15 | I. Fundamentals | Intervals |

|

| 16 | I. Fundamentals | Triads |

|

| 17 | I. Fundamentals | Seventh Chords |

|

| 18 | I. Fundamentals | Inversion and Figured Bass |

|

| 19 | I. Fundamentals | Roman Numerals and SATB Chord Construction | |

| 20 | I. Fundamentals | Texture |

|

| 21 | II. Counterpoint and Galant Schemas | Introduction to Species Counterpoint |

|

| 22 | II. Counterpoint and Galant Schemas | First-Species Counterpoint |

|

| 23 | II. Counterpoint and Galant Schemas | Second-Species Counterpoint |

|

| 24 | II. Counterpoint and Galant Schemas | Third-Species Counterpoint |

|

| 25 | II. Counterpoint and Galant Schemas | Fourth-Species Counterpoint |

|

| 26 | II. Counterpoint and Galant Schemas | Fifth-Species Counterpoint |

|

| 27 | II. Counterpoint and Galant Schemas | Gradus ad Parnassum Exercises | |

| 28 | II. Counterpoint and Galant Schemas | 16th-Century Contrapuntal Style |

|

| 29 | II. Counterpoint and Galant Schemas | High Baroque Fugal Exposition |

|

| 30 | II. Counterpoint and Galant Schemas | Ground Bass |

|

| 31 | II. Counterpoint and Galant Schemas | Galant Schemas – Summary | |

| 32 | II. Counterpoint and Galant Schemas | Galant schemas – The Rule of the Octave and Harmonizing the Scale with Sequences |

|

| 33 | II. Counterpoint and Galant Schemas | Galant Schemas |

|

| 34 | III. Form | Foundational Concepts for Phrase-Level Forms |

|

| 35 | III. Form | The Phrase, Archetypes, and Unique Forms |

|

| 36 | III. Form | Hybrid Phrase-Level Forms |

|

| 37 | III. Form | Expansion and Contraction at the Phrase Level |

|

| 38 | III. Form | Formal Sections in General | |

| 39 | III. Form | Binary Form |

|

| 40 | III. Form | Ternary Form |

|

| 41 | III. Form | Sonata Form |

|

| 42 | III. Form | Rondo |

|

| 43 | IV. Diatonic Harmony, Tonicization, and Modulation | Introduction to Harmony, Cadences, and Phrase Endings |

|

| 44 | IV. Diatonic Harmony, Tonicization, and Modulation | Strengthening Endings with V7 |

|

| 45 | IV. Diatonic Harmony, Tonicization, and Modulation | Strengthening Endings with Strong Predominants |

|

| 46 | IV. Diatonic Harmony, Tonicization, and Modulation | Embellishing Tones |

|

| 47 | IV. Diatonic Harmony, Tonicization, and Modulation | Strengthening Endings with Cadential 6/4 |

|

| 48 | IV. Diatonic Harmony, Tonicization, and Modulation | Prolonging Tonic at Phrase Beginnings with V6 and Inverted V7s | |

| 49 | IV. Diatonic Harmony, Tonicization, and Modulation | Performing Harmonic Analysis Using the Phrase Model |

|

| 50 | IV. Diatonic Harmony, Tonicization, and Modulation | Prolongation at Phrase Beginnings using the Leading-Tone Chord |

|

| 51 | IV. Diatonic Harmony, Tonicization, and Modulation | 6/4 Chords as Forms of Prolongation |

|

| 52 | IV. Diatonic Harmony, Tonicization, and Modulation | Plagal Motion as a Form of Prolongation |

|

| 53 | IV. Diatonic Harmony, Tonicization, and Modulation | La (Scale Degree 6) in the Bass at Beginnings, Middles, and Endings |

|

| 54 | IV. Diatonic Harmony, Tonicization, and Modulation | The Mediant Harmonizing Mi (Scale Degree 3) in the Bass |

|

| 55 | IV. Diatonic Harmony, Tonicization, and Modulation | Predominant Seventh Chords |

|

| 56 | IV. Diatonic Harmony, Tonicization, and Modulation | Tonicization |

|

| 57 | IV. Diatonic Harmony, Tonicization, and Modulation | Extended Tonicization and Modulation to Closely Related Keys |

|

| 58 | V. Chromaticism | Modal Mixture |

|

| 59 | V. Chromaticism | Neapolitan 6th (♭II6) |

|

| 60 | V. Chromaticism | Augmented Sixth Chords |

|

| 61 | V. Chromaticism | Common-Tone Chords (CTº7 & CT+6) |

|

| 62 | V. Chromaticism | Harmonic Elision |

|

| 63 | V. Chromaticism | Chromatic Modulation |

|

| 64 | V. Chromaticism | Reinterpreting Diminished Seventh Chords |

|

| 65 | V. Chromaticism | Augmented Options |

|

| 66 | V. Chromaticism | Equal Divisions of the Octave |

|

| 67 | V. Chromaticism | Chromatic Sequences |

|

| 68 | V. Chromaticism | Parallel Chromatic Sequences |

|

| 69 | V. Chromaticism | The Omnibus Progression |

|

| 70 | V. Chromaticism | Altered and Extended Dominant Chords |

|

| 71 | V. Chromaticism | Neo-Riemannian Triadic Progressions |

|

| 72 | V. Chromaticism | Mediants |

|

| 73 | VI. Jazz | Swing Rhythms |

|

| 74 | VI. Jazz | Chord Symbols |

|

| 75 | VI. Jazz | Jazz Voicings |

|

| 76 | VI. Jazz | ii–V–I | |

| 77 | VI. Jazz | Embellishing Chords |

|

| 78 | VI. Jazz | Substitutions |

|

| 79 | VI. Jazz | Chord-Scale Theory |

|

| 80 | VI. Jazz | Blues Harmony |

|

| 81 | VI. Jazz | Blues Melodies and the Blues Scale |

|

| 82 | VII. Popular Music | Rhythm and Meter in Pop Music |

|

| 83 | VII. Popular Music | Drumbeats |

|

| 84 | VII. Popular Music | Melody and Phrasing |

|

| 85 | VII. Popular Music | Introduction to Form in Popular Music | |

| 86 | VII. Popular Music | AABA Form and Strophic Form |

|

| 87 | VII. Popular Music | Verse-Chorus Form |

|

| 88 | VII. Popular Music | Introduction to Harmonic Schemas in Pop Music | |

| 89 | VII. Popular Music | Blues-Based Schemas |

|

| 90 | VII. Popular Music | Four-Chord Schemas |

|

| 91 | VII. Popular Music | Classical Schemas (in a Pop Context) |

|

| 92 | VII. Popular Music | Puff Schemas |

|

| 93 | VII. Popular Music | Modal Schemas |

|

| 94 | VII. Popular Music | Pentatonic Harmony |

|

| 95 | VII. Popular Music | Fragile, Absent, and Emergent Tonics |

|

| 96 | VIII. 20th- and 21st-Century Techniques | Twentieth-Century Rhythmic Techniques | |

| 97 | VIII. 20th- and 21st-Century Techniques | Pitch and Pitch Class |

|

| 98 | VIII. 20th- and 21st-Century Techniques | Intervals in Integer Notation |

|

| 99 | VIII. 20th- and 21st-Century Techniques | Pitch-Class Sets, Normal Order, and Transformations |

|

| 100 | VIII. 20th- and 21st-Century Techniques | Set Class and Prime Form |

|

| 101 | VIII. 20th- and 21st-Century Techniques | Interval-Class Vectors |

|

| 102 | VIII. 20th- and 21st-Century Techniques | Analyzing with Set Theory (or not!) |

|

| 103 | VIII. 20th- and 21st-Century Techniques | Diatonic Modes |

|

| 104 | VIII. 20th- and 21st-Century Techniques | Collections |

|

| 105 | VIII. 20th- and 21st-Century Techniques | Analyzing with Modes, Scales, and Collections |

|

| 106 | IX. Twelve-Tone Music | Basics of Twelve-Tone Theory |

|

| 107 | IX. Twelve-Tone Music | Naming Conventions for Rows |

|

| 108 | IX. Twelve-Tone Music | Row Properties |

|

| 109 | IX. Twelve-Tone Music | Analysis Examples – Webern Op. 21 and 24 | |

| 110 | IX. Twelve-Tone Music | Composing with Twelve Tones |

|

| 111 | IX. Twelve-Tone Music | History and Context of Serialism | |

| 112 | X. Orchestration | Core Principles of Orchestration |

|

| 113 | X. Orchestration | Subtle Color Changes |

|

| 114 | X. Orchestration | Transcription from Piano |

|

| 115 | XI. Rhythm and Meter | Notating Rhythm [crosslist] |

|

| 116 | XI. Rhythm and Meter | Simple Meter and Time Signatures [crosslist] |

|

| 117 | XI. Rhythm and Meter | Compound Meter and Time Signatures [crosslist] |

|

| 118 | XI. Rhythm and Meter | Other Rhythmic Essentials [crosslist] |

|

| 119 | XI. Rhythm and Meter | Hypermeter |

|

| 120 | XI. Rhythm and Meter | Metrical Dissonance |

|

| 121 | XI. Rhythm and Meter | Swing Rhythms [crosslist] |

|

| 122 | XI. Rhythm and Meter | Rhythm and Meter in Pop Music [crosslist] |

|

| 123 | XI. Rhythm and Meter | Drumbeats [crosslist] |

|

| 124 | XI. Rhythm and Meter | Twentieth-Century Rhythmic Techniques [crosslist] |

|

In church modes, authentic modes are those that range from final to final.

A mode with a range of a fifth above and fourth below its tonic.

.front-matter h6 {

font-size: 1.25em;

}

.textbox--sidebar {

float: right;

margin: 1em 0 1em 1em;

max-width: 45%;

}

.textbox.textbox--key-takeaways .textbox__header p {

font: sans-serif !important;

font-weight: bold;

text-transform: uppercase;

font-style: normal;

font-size: larger;

}

.button, a.call-to-action, button, input[type=submit] {

border-radius: 3px;

border-style: solid;

border-width: 2px;

display: inline-block;

font-family: Karla, sans-serif;

font-weight: 600;

line-height: 1.5;

padding: .875rem 3.25rem;

text-align: center;

text-decoration: none;

text-transform: uppercase;

vertical-align:middle

}

Connects two or more notes of the same pitch; notes after the initial one are not rearticulated.

Key Takeaways

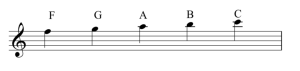

In Western musical notation, pitches are designated by the first seven letters of the Latin alphabet: A, B, C, D, E, F, and G. After G these letter names repeat in a loop: A, B, C, D, E, F, G, A, B, C, D, E, F, G, A, B, C, etc. This loop of letter names exists because musicians and music theorists today accept what is called octave equivalence, or the assumption that pitches separated by an octave should have the same letter name. More information about this concept can be found in the next chapter, The Keyboard and the Grand Staff.

This assumption varies with milieu. For example, some ancient Greek music theorists did not accept octave equivalence. These theorists used more than seven letters of the Greek alphabet to name pitches.

Clefs and Ranges

The Notation of Notes, Clefs, and Ledger Lines chapter introduced four clefs: treble, bass, alto, and tenor. A clef indicates which pitches are assigned to the lines and spaces on a staff. In the next chapter, The Keyboard and the Grand Staff, we will see that having multiple clefs makes reading different ranges easier. The treble clef is typically used for higher voices and instruments, such as a flute, violin, trumpet, or soprano voice. The bass clef is usually utilized for lower voices and instruments, such as a bassoon, cello, trombone, or bass voice. The alto clef is primarily used for the viola, a mid-ranged instrument, while the tenor clef is sometimes employed in cello, bassoon, and trombone music (although the principal clef used for these instruments is the bass clef).

Each clef indicates how the lines and spaces of the staff correspond to pitch. Memorizing the patterns for each clef will help you read music written for different voices and instruments.

Reading Treble Clef

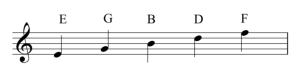

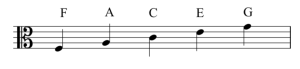

The treble clef is one of the most commonly used clefs today. Example 1 shows the letter names used for the lines of a staff when a treble clef is employed. One mnemonic device that may help you remember this order of letter names is "Every Good Bird Does Fly" (E, G, B, D, F). As seen in Example 1, the treble clef wraps around the G line (the second line from the bottom). For this reason, it is sometimes called the "G clef."

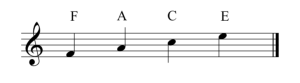

Example 2 shows the letter names used for the spaces of a staff with a treble clef. Remembering that these letter names spell the word "face" may make identifying these spaces easier.

Reading Bass Clef

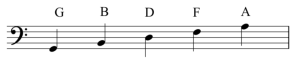

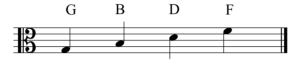

The other most commonly used clef today is the bass clef. Example 3 shows the letter names used for the lines of a staff when a bass clef is employed. A mnemonic device for this order of letter names is “Good Bikes Don’t Fall Apart” (G, B, D, F, A). The bass clef is sometimes called the “F clef”; as seen in Example 3, the dot of the bass clef begins on the F line (the second line from the top).

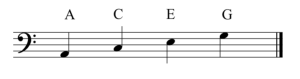

Example 4 shows the letter names used for the spaces of a staff with a bass clef. The mnemonic device "All Cows Eat Grass" (A, C, E, G) may make identifying these spaces easier.

Reading Alto Clef

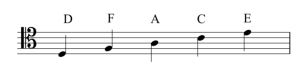

Example 5 shows the letter names used for the lines of the staff with the alto clef, which is less commonly used today. The mnemonic device “Fat Alley Cats Eat Garbage” (F, A, C, E, G) may help you remember this order of letter names. As seen in Example 5, the center of the alto clef is indented around the C line (the middle line). For this reason it is sometimes called a "C clef."

Example 6 shows the letter names used for the spaces of a staff with an alto clef, which can be remembered with the mnemonic device “Grand Boats Drift Flamboyantly” (G, B, D, F).

Reading Tenor Clef

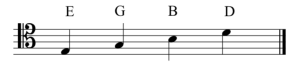

The tenor clef, another less commonly used clef, is also sometimes called a “C clef,” but the center of the clef is indented around the second line from the top. Example 7 shows the letter names used for the lines of a staff when a tenor clef is employed, which can be remembered with the mnemonic device “Dodges, Fords, and Chevrolets Everywhere” (D, F, A, C, E):

Example 8 shows the letter names used for the spaces of a staff with a tenor clef. The mnemonic device "Elvis's Guitar Broke Down" (E, G, B, D) may make identifying these spaces easier.

Ledger Lines

When notes are too high or low to be written on a staff, small lines are drawn to extend the staff. You may recall from the previous chapter that these extra lines are called ledger lines. Ledger lines can be used to extend a staff with any clef. Example 9 shows ledger lines above a staff with a treble clef:

Notice that each space and line above the staff gets a letter name with ledger lines, as if the staff were simply continuing upwards. The same is true for ledger lines below a staff, as shown in Example 10:

Notice that each space and line below the staff gets a letter name with ledger lines, as if the staff were simply continuing downwards.

- The Staff, Clefs, and Ledger Lines (musictheory.net)

- Flashcards for Treble, Bass, Alto, and Tenor Clefs (Richman Music School)

- Printable Treble Clef Flash Cards (Samuel Stokes Music) (pages 3 to 5)

- Printable Bass Clef Flash Cards (Samuel Stokes Music) (pages 1 to 3)

- Printable Alto Clef Flash Cards (Samuel Stokes Music)

- Printable Tenor Clef Flash Cards (Samuel Stokes Music)

- Paced Game: Treble Clef (Tone Savvy)

- Paced Game: Bass Clef (Tone Savvy)

- Paced Game: Alto Clef (Tone Savvy)

- Paced Game: Tenor Clef (Tone Savvy)

Easy

Medium

- Worksheets in Treble Clef (.pdf)

- Treble Clef with Ledger Lines (.pdf)

- Worksheets in Bass Clef (.pdf, .pdf)

- Bass Clef with Ledger Lines (.pdf)

- Worksheets in Alto Clef (.pdf, .pdf)

- Worksheets in Tenor Clef (.pdf)

Advanced

- All Clefs (.pdf)

.front-matter h6 {

font-size: 1.25em;

}

.textbox--sidebar {

float: right;

margin: 1em 0 1em 1em;

max-width: 45%;

}

.textbox.textbox--key-takeaways .textbox__header p {

font: sans-serif !important;

font-weight: bold;

text-transform: uppercase;

font-style: normal;

font-size: larger;

}

a:link {

text-decoration: none;

}

.button {

background-color: ivory;

text-color: purple;

}

A type of motion where a chord tone moves by step to another tone, then moves back to the original chord tone. For example, C–D–C above a C major chord would be an example of neighboring motion, in which D can be described as a neighbor tone. Entire harmonies may be said to be neighboring when embellishing another harmony, when the voice-leading between the two chords involves only neighboring and common-tone motion (as in the common-tone diminished seventh chord).

Substituting a major I chord for a minor I chord (for example, using C major instead of C minor in a piece that is in C minor overall).