II. Counterpoint and Galant Schemas

23

Kris Shaffer and Mark Gotham

Key Takeaways

- First-species counterpoint is a traditional compositional exercise that teaches beginning musicians to consider how to start and end melodic lines, and most importantly, how to keep them independent of each other.

- When writing in first species, follow these rules:

- Begin on a perfect unison, fifth, or octave.

- Both voices move at exactly the same rate and have no rhythmic variety (for example, all notes are whole notes).

- Harmonically, the intervals between the two voices are all consonances.

- Melodically, prefer stepwise motion and leap only occasionally. Melodic leaps of a tritone or seventh are forbidden.

- Parallel perfect consonances are forbidden.

- End with a perfect unison or octave.

- This chapter presents additional guidelines that will help in writing a successful first-species counterpoint.

Counterpoint is the mediation of two or more musical lines into a meaningful and pleasing whole. In first-species counterpoint, we not only write a smooth melody that has its own integrity of shape, variety, and goal-directed motion, but we also write a second melody that contains these traits. Further, and most importantly, we combine these melodies to create a whole texture that is smooth, that exhibits variety and goal-oriented motion, and in which these melodies both maintain their independence and fuse together into consonant simultaneities (the general term for two or more notes sounding at the same time).

In first-species counterpoint, we begin with a cantus firmus (new or existing) and compose a single new line—called the counterpoint—above or below it. That new line contains one note for every note in the cantus: both the cantus firmus and the counterpoint will be all whole notes. Thus, first species is sometimes called "one-against-one" or 1:1 counterpoint.

The Counterpoint Line

In general, the counterpoint should follow the principles of writing a good cantus firmus discussed in the previous chapter, Introduction to Species Counterpoint. There are some minor differences, to be discussed below, but generally a first-species counterpoint should consist of two cantus-firmus-quality lines.

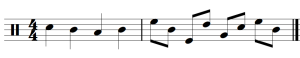

Example 1 shows the complete exercises of first-species counterpoint from Part I of Gradus ad Parnassum. Each example sees one of the cantus firmi we've already met combined with a new counterpoint line either above or below. We've annotated each one with the interval that the counterpoint line makes with the cantus firmus. For the complete examples from Gradus ad Parnassum as exercises, solutions, and annotations, see Gradus ad Parnassum Exercises.

https://musescore.com/user/32728834/scores/8488049/embed

Example 1. All first-species exercises from Gradus ad Parnassum.

Beginning and Ending

Beginning a first-species counterpoint

Note that each exercise in Example 1 begins with a perfect consonance. This creates a sense of stability at the opening of the line.

When writing a counterpoint above a cantus firmus, the first note of the counterpoint should be do [latex](\hat1)[/latex] or sol [latex](\hat5)[/latex] (a P1, P5, or P8 above the cantus).

When writing a counterpoint below a cantus firmus, the first note of the counterpoint must always be on the modal final, do [latex](\hat1)[/latex] (P1 or P8 below the cantus firmus). Beginning on sol [latex](\hat5)[/latex] would create a dissonant fourth; beginning on fa [latex](\hat4)[/latex] would create a P5 but confuse listeners about the tonal context, since fa–do [latex](\hat4-\hat1)[/latex] at the beginning of a piece is easily misheard as do–sol [latex](\hat1-\hat5)[/latex].

Ending a first-species counterpoint

The final note of the counterpoint must always be do [latex](\hat1)[/latex] (P1 or P8 above/below the cantus).

To approach this ending smoothly, with variety, and with strong goal orientation, always approach the final interval by contrary stepwise motion, as follows:

- If the cantus ends re–do [latex](\hat2-\hat1)[/latex], the counterpoint’s final two pitches should be ti–do [latex](\hat7-\hat1)[/latex].

- If the cantus ends ti–do [latex](\hat7-\hat1)[/latex], the counterpoint’s final two pitches should be re–do [latex](\hat2-\hat1)[/latex].

Thus, the penultimate bar will either be a third or a sixth between the two lines (Example 2). This ending formula is known as the clausula vera. The exercises in Example 1 each end with a clausula vera.

https://musescore.com/user/32728834/scores/8513480/embed

Example 2. Examples of the clausula vera.

Independence of the Lines

Like the cantus firmus, the counterpoint line should have a single climax. To maintain the independence of the lines and the smoothness of the entire passage (so no one moment is hyper-emphasized by a double climax), these climaxes should not coincide.penultimate

A single repeat/tie in the counterpoint is allowed, but try to avoid repeating at all. This promotes variety in the exercise, since there are so few notes to begin with.

Avoid voice crossing. Voice crossings diminish the independence of the lines and make them more difficult to distinguish by ear.

Avoid voice overlap, where one voice leaps past the previous note of the other voice. For example, if the upper part sings an E4, the lower part cannot sing an F4 in the following bar. This also helps maintain the independence of the lines.

Intervals and Motion

The interval between the cantus firmus and counterpoint at any moment should not exceed a perfect twelfth (octave plus fifth). In general, try to keep the two lines within an octave where possible, and only exceed a tenth in “emergencies” and only briefly (one or two notes). When the voices are too far apart, tonal fusion is diminished. Further, it can diminish performability, which, though not an essential principle of human cognition, is an important consideration for composers, and it has a direct effect on the smoothness, melodic integrity, and tonal fusion of what listeners hear during a performance.

In general, all harmonic consonances are allowed. However, unisons should only be used for the first and last intervals. Unisons are very stable and serve best as goals rather than midpoints. They also diminish the independence of the lines.

Imperfect consonances are preferable to perfect consonances for all intervals other than the first and last dyads, in order to heighten the sense of arrival at the end and to promote a sense of motion toward that arrival. In all cases, aim for a variety of harmonic intervals over the course of the exercise.

Never use two perfect consonances of the same size in a row: P5–P5 or P8–P8. This includes both simple and compound intervals; for example, P5–P12 is considered the same as P5–P5. (Two different perfect consonances in a row, such as P8–P5, are allowed, but try to follow every perfect consonance with an imperfect consonance if possible.) Parallel fifths and octaves promote tonal fusion at the expense of melodic independence, and these consecutive stable sonorities also limit variety and motion in the exercise. Thus, they are far from ideal, and are to be avoided in species counterpoint.

Vary the types of motion between successive intervals, aiming to use each type (except perhaps oblique motion). Contrary motion is best for variety and preserving the independence of the lines, so it should be preferred where possible.

Because similar and parallel motion diminish variety and melodic independence, their use should be mediated by other factors:

- Do not use more than three of the same imperfect consonance type in a row (e.g., three thirds in a row).

- Never move into a perfect consonance by similar motion (this is called direct fifths/octaves. This draws too much attention to an interval that already stands out of the texture.

- Avoid combining similar motion with leaps, especially large ones.

- First-Species Counterpoint A (.pdf, .mscx). Asks students to compose a first-species example and do error detection.

- For the complete set of Fux exercises, see the Gradus ad Parnassum chapter.

Key Takeaways

- A beat is a pulse in music that regularly recurs.

- Simple meters are meters in which the beat divides into two, and then further subdivides into four.

- Duple meters have groupings of two beats, triple meters have groupings of three beats, and quadruple meters have groupings of four beats.

- There are different conducting patterns for duple, triple, and quadruple meters.

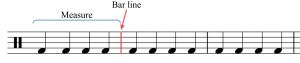

- A measure is equivalent to one group of beats (duple, triple, or quadruple). Measures are separated by bar lines.

- Time signatures in simple meters express two things: how many beats are contained in each measure (the top number), and the beat unit (the bottom number), which refers to the note value that is the beat.

- A beam visually connects notes together, grouping them by beat. Beaming changes in different time signatures.

- Notes below the middle line on a staff are up-stemmed, while notes above the middle line on a staff are down-stemmed. Flag direction works similarly.

In Rhythmic and Rest Values, we discussed the different rhythmic values of notes and rests. Musicians organize rhythmic values into various meters, which are—broadly speaking—formed as the result of recurrent patterns of accents in musical performances.

Terminology

Listen to the following performance by the contemporary musical group Postmodern Jukebox ( Example 1). They are performing a cover of the song "Wannabe" by the Spice Girls (originally released in 1996). Beginning at 0:11, it is easy to tap or clap along to this recording. What you are tapping along to is called a beat—a pulse in music that regularly recurs.

Example 1. A cover of "Wannabe" performed by Postmodern Jukebox; listen starting at 0:11.

Example 1 is in a simple meter: a meter in which the beat divides into two, and then further subdivides into four. You can feel this yourself by tapping your beat twice as fast; you might also think of this as dividing your beat into two smaller beats.

Different numbers of beats group into different meters. Duple meters contain beats that are grouped into twos, while Triple meters contain beats that are grouped into threes, and Quadruple meters contain beats that are grouped into fours.

Listening to Simple Meters

Let's listen to examples of simple duple, simple triple, and simple quadruple meters. A simple duple meter contains two beats, each of which divides into two (and further subdivides into four). "The Stars and Stripes Forever" (1896), written by John Philip Sousa, is in a simple duple meter.

Listen to Example 2, and tap along, feeling how the beats group into sets of two:

Example 2. "The Stars and Stripes Forever" played by the Dallas Winds.

A simple triple meter contains three beats, each of which divides into two (and further subdivides into four). Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart's "Minuet in F major," K.2 (1774) is in a simple triple meter. Listen to Example 3, and tap along, feeling how the beats group into sets of three:

Example 3. Mozart's "Minuet in F major," played by Alan Huckleberry.

Finally, a simple quadruple meter contains four beats, each of which divides into two (and further subdivides into four). The song "Cake" (2017) by Flo Rida is in a simple quadruple meter. Listen to Example 4 starting at 0:45 and tap along, feeling how the beats group into sets of four:

Example 4. "Cake" by Flo Rida; listen starting at 0:45.

As you can hear and feel (by tapping along), musical compositions in a wide variety of styles are governed by meter. You might practice identifying the meters of some of your favorite songs or musical compositions as simple duple, simple triple, or simple quadruple; listening carefully and tapping along is the best way to do this. Note that simple quadruple meters feel similar to simple duple meters, since four beats can be divided into two groups of two beats. It may not always be immediately apparent if a work is in a simple duple or simple quadruple meter by listening alone.

Conducting Patterns

If you have ever sung in a choir or played an instrument in a band or orchestra, then you have likely had experience with a conductor. Conductors have many jobs. One of these jobs is to provide conducting patterns for the musicians in their choir, band, or orchestra. Conducting patterns serve two main purposes: first, they establish a tempo, and second, they establish a meter.

The three most common conducting patterns outline duple, triple, and quadruple meters. Duple meters are conducted with a downward/outward motion (step 1), followed by an upward motion (step 2), as seen in Example 5. Triple meters are conducted with a downward motion (step 1), an outward motion (step 2), and an upward motion (step 3), as seen in Example 6. Quadruple meters are conducted with a downward motion (step 1), an inward motion (step 2), an outward motion (step 3), and an upward motion (step 4), as seen in Example 7:

Beat 1 of each of these measures is considered a downbeat . A downbeat is conducted with a downward motion, and you may hear and feel that it has more "weight" or "heaviness" then the other beats. An upbeat is the last beat of any measure. Upbeats are conducted with an upward motion, and you may feel and hear that they are anticipatory in nature.

Example 8 shows a short video demonstrating these three conducting patterns:

Example 8. Dr. John Lopez (Texas A&M University, Kingsville) demonstrates duple, triple, and quadruple conducting patterns.

You can practice these conducting patterns while listening to Example 2 (duple), Example 3 (triple), and Example 4 (quadruple) above.

Time Signatures

In Western musical notation, beat groupings (duple, triple, quadruple, etc.) are shown using bar lines, which separate music into measures (also called bars), as shown in Example 9. Each measure is equivalent to one beat grouping.

In simple meters, time signatures (also called meter signatures) express two things: 1) how many beats are contained in each measure, and 2) the beat unit (which note value gets the beat). Time signatures are expressed by two numbers, one above the other, placed after the clef (Example 10).

A time signature is not a fraction, though it may look like one; note that there is no line between the two numbers. In simple meters, the top number of a time signature represents the number of beats in each measure, while the bottom number represents the beat unit.

In simple meters, the top number is always 2, 3, or 4, corresponding to duple, triple, or quadruple beat patterns. The bottom number is usually one of the following:

- 2, which means the half note gets the beat.

- 4, which means the quarter note gets the beat.

- 8, which means the eighth note gets the beat.

You may also see the bottom number 16 (the sixteenth note gets the beat) or 1 (the whole note gets the beat) in simple meter time signatures.

There are two additional simple meter time signatures, which are 𝄴 (common time) and 𝄵 (cut time). Common time is the equivalent of [latex]\mathbf{^4_4}[/latex] (simple quadruple—four beats per measure), while cut time is the equivalent of [latex]\mathbf{^2_2}[/latex] (simple duple—two beats per measure).

Counting in Simple Meter

Counting rhythms aloud is important for musical performance; as a singer or instrumentalist, you must be able to perform rhythms that are written in Western musical notation. Conducting while counting rhythms is highly recommended and will help you to keep a steady tempo. Please note that your instructor may employ a different counting system. Open Music Theory privileges American traditional counting, but this is not the only method.

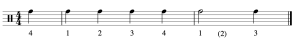

Example 11 shows a rhythm in a [latex]\mathbf{^4_4}[/latex] time signature, which is a simple quadruple meter. This time signature means that there are four beats per measure (the top 4) and that the quarter note gets the beat (the bottom 4).

- In each measure, each quarter note gets a count, expressed with Arabic numerals—"1, 2, 3, 4."

- When notes last longer than one beat (such as a half or whole note in this example), the count is held over multiple beats. Beats that are not counted out loud are written in parentheses.

- When the beat in a simple meter is divided into two, the divisions are counted aloud with the syllable “and,” which is usually notated with the plus sign (+). So, if the quarter note gets the beat, the second eighth note in each beat would be counted as “and.”

- Further subdivisions at the sixteenth-note level are counted as “e” (pronounced as a long vowel, as in the word “see”) and “a” (pronounced “uh”). At the thirty-second-note level, further subdivisions add the syllable “ta” in between each of the previous syllables.

Example 11. Rhythm in 4/4 time.

Simple duple meters have only two beats and simple triple meters have only three, but the subdivisions are counted the same way (Example 12).

Example 12. Simple duple meters have two beats per measure; simple triple meters have three.

Like with notes that last for two or more beats, beats that are not articulated because of rests, ties, and dots are also not counted out loud. These beats are usually written in parentheses, as shown in Example 13:

Example 13. Beats that are not counted out loud are put in parentheses.

When an example begins with a pickup note (anacrusis), your count will not begin on "1," as shown in Example 14. An anacrusis is counted as the last note(s) of an imaginary measure. When a work begins with an anacrusis, the last measure is usually shortened by the length of the anacrusis. This is demonstrated in Example 14: the anacrusis is one quarter note in length, so the last measure is only three beats long (i.e., it is missing one quarter note).

Counting with Beat Units of 2, 8, and 16

In simple meters with other beat units (shown in the bottom number of the time signature), the same counting patterns are used for the beats and subdivisions, but they correspond to different note values. Example 15 shows a rhythm with a [latex]\mathbf{^4_4}[/latex] time signature, followed by the same rhythms with different beat units. Each of these rhythms sounds the same and is counted the same. They are also all considered simple quadruple meters. The difference in each example is the bottom number of the time signature—which note gets the beat unit (quarter, half, eighth, or sixteenth).

Example 15. The same counted rhythm, as written in a meter with (a) a quarter-note beat, (b) a half-note beat, (c) an eighth-note beat, and (d) a sixteenth-note beat.

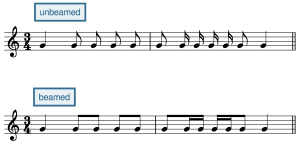

Beaming, Stems, Flags, and Multi-Measure Rests

Beams connect notes together by beat. As Example 16 shows, this means that beaming changes depending on the time signature. In the first measure, sixteenth notes are grouped into sets of four, because four sixteenth notes in a [latex]\mathbf{^4_4}[/latex] time signature are equivalent to one beat. In the second measure, however, sixteenth notes are grouped into sets of two, because one beat in a [latex]\mathbf{^4_8}[/latex] time signature is only equivalent to two sixteenth notes.

Example 16. Beaming in two different meters.

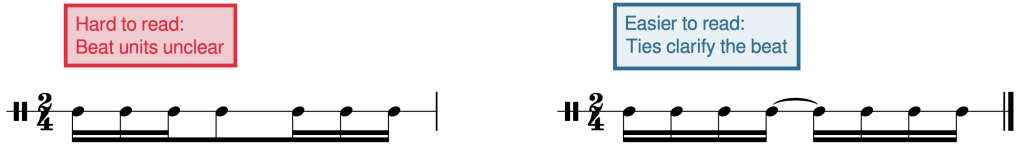

Note that in vocal music, beaming is sometimes only used to connect notes sung on the same syllable. If you are accustomed to music without beaming, you may need to pay special attention to beaming conventions until you have mastered them. In the top staff of Example 17, the eighth notes are not grouped with beams, making it difficult to see where beats 2 and 3 in the triple meter begin. The bottom staff shows that if we re-notate the rhythm so that the notes that fall within the same beat are grouped together with a beam, it makes the music much easier to read. Note that these two rhythms sound the same, even though they are beamed differently. The ability to group events according to a hierarchy is an important part of human perception, which is why beaming helps us visually parse notated musical rhythms—the metrical structure provides a hierarchy that we show using notational tools like beaming.

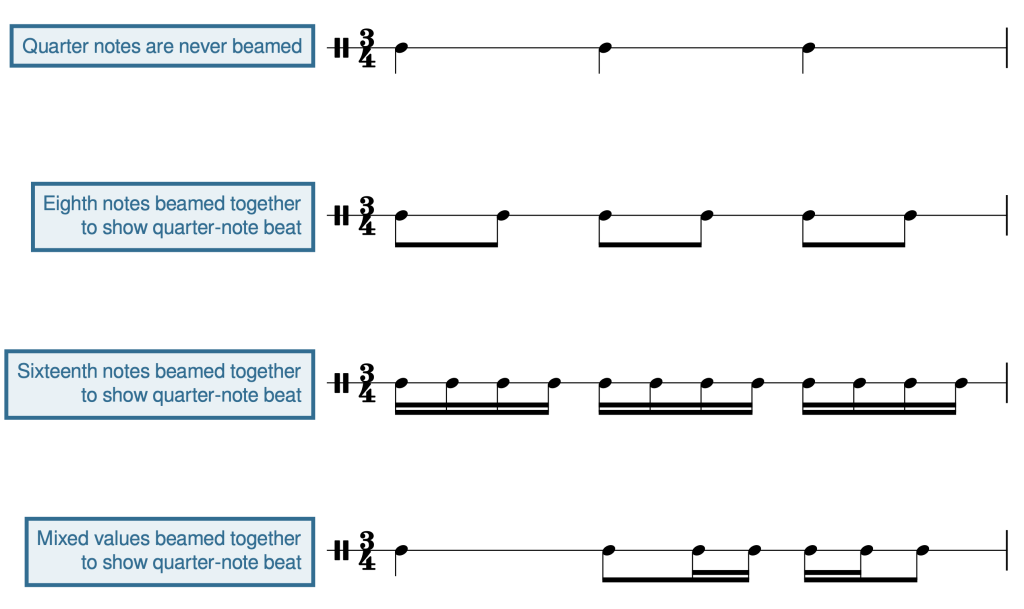

Example 18 shows several different note values beamed together to show the beat unit. The first line does not require beams because quarter notes are never beamed, but all subsequent lines do need beams to clarify beats.

The second measure of Example 19 shows that when notes are grouped together with beams, the stem direction is determined by the note farthest from the middle line. On beat 1 of measure 2, this note is E5, which is above the middle line, so down-stems are used. Beat 2 uses up-stems because the note farthest from the middle line is the E4 below it.

Flagging is determined by stem direction (Example 20). Notes above the middle line receive a down-stem (on the left) and an inward-facing flag (facing right). Notes below the middle line receive an up-stem (on the right) and an outward-facing flag (facing left). Notes on the middle line can be flagged in either direction, usually depending on the contour of the musical line.

Partial beams can be used for mixed rhythmic groupings, as shown in Example 21. Sometimes these beaming conventions look strange to students who have had less experience with reading beamed music. If this is the case, you will want to pay special attention to how the notes in Example 21 are beamed.

Example 21. Partial beams are used for some mixed rhythmic groupings.

Rests that last for multiple full measures are sometimes notated as seen in Example 22. This example indicates that the musician is to rest for a duration of four full measures.

A Note on Ties

We have already encountered ties that can be used to extend a note over a measure line. But ties can also be used like beams to clarify the metrical structure within a measure. In the first measure of Example 23, beat 2 begins in the middle of the eighth note, making it difficult to see the metrical structure. Breaking the eighth note into two sixteenth notes connected by a tie, as shown in the second measure, clearly shows the beginning of beat 2.

- Simple Meter Tutorial (musictheory.net)

- Video Tutorial on Simple Meter, Beats, and Beaming (YouTube)

- Conducting Patterns (YouTube)

- Simple Meter Time Signatures (liveabout.com)

- Video Tutorial on Counting Simple Meters (One Minute Music Lessons)

- Simple Meter Counting (YouTube)

- Beaming Rules (Music Notes Now)

- Beaming Examples (Dr. Sebastian Anthony Birch)

- Time Signatures and Rhythms (.pdf)

- Terminology, Bar Lines, Fill-in-rhythms, Re-beaming (.pdf)

- Meters, Time Signatures, Re-beaming (website)

- Bar Lines, Time Signatures, Counting (.pdf)

- Time Signatures, Re-beaming, p. 4 (.pdf)

- Fill-in-rhythms (.pdf)

- Time Signatures (.pdf, .pdf)

- Bar Lines (.pdf, .pdf, .pdf)