III. Form

39

Brian Jarvis

Key Takeaways

Overview of Formal Sections in General

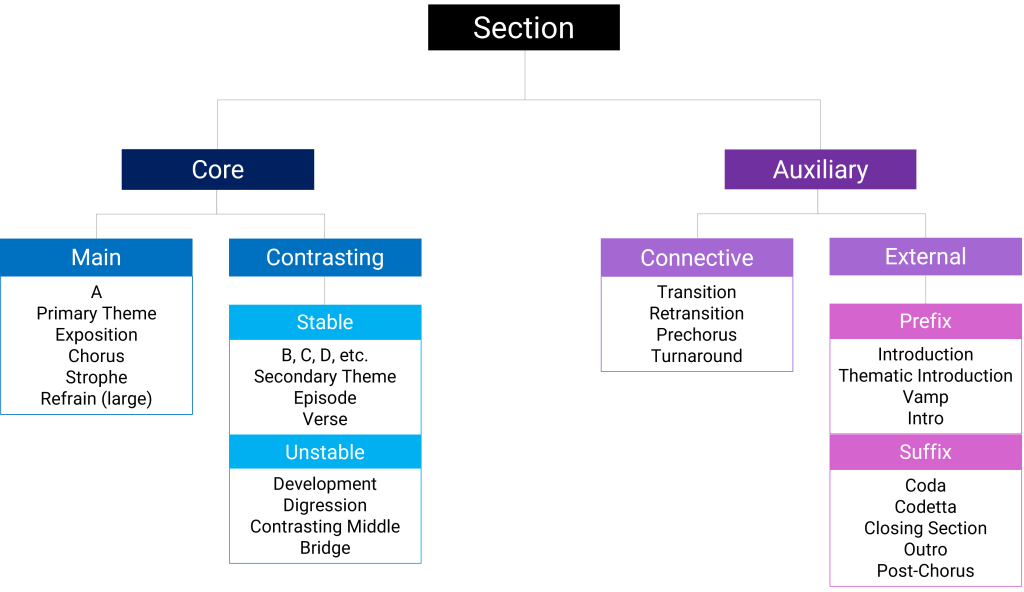

Understanding the form of a musical work typically involves breaking it down into spans of time, based on how each span is similar to and/or contrasts with other spans. These spans are then classified based on the identity of their musical material and how the section “functions” in the context of the piece. The two largest categories of formal function are core sections and auxiliary sections.[1] Example 1 below summarizes the hierarchical relationship between some of the most common section types. At the broadest level, musical sections are either core or auxiliary. Core sections are either main or contrasting, and auxiliary sections are either external or connective.

Core Sections

The core sections identified in Example 1 typically introduce and repeat a work’s primary musical content. You can think of them as the sections you might sing for someone if they asked you how the work “goes.” You can also think of core sections as containing the work’s themes, though the term “theme” can be used in a broad or specific sense. Core sections also tend to repeat, which is another reason they will often make a stronger impression on your memory.

Main Sections

Main sections are typically the first section that presents primary musical content; they are usually repeated later in the work and are characterized by a relative sense of stability.

Terminology

The terms for main sections change depending upon the conventions of the genre and form (if it is a form with a name). When thinking about form in general, the main section should be called A, but within a known form, it may go by many names, including but not limited to:

- primary theme (sonata)

- refrain (rondo or verse-refrain)

- exposition (sonata)

- theme from a set of variations

- chorus (verse-chorus)

- dance chorus (verse-chorus)

- strophe (AABA and strophic)

Contrasting Sections

Contrasting sections are hard to generalize, since they can vary in affect and stability. In some cases, the section is perfectly stable, and it contrasts mainly because it comes second instead of first; in other cases, a contrasting section may be the most unstable section of the work.

Unstable contrasting sections may share many musical features with connective auxiliary sections (defined below). The distinction lies in whether or not it is considered a core section: contrasting sections sound like a primary place in the work, whereas connective sections sound like a place between two core sections. In cases where the line between the two is blurry, a decision can be made based on the conventions of the overall form of the piece, or multiple formal descriptors (e.g., becoming) can be used to create an accurate and unforced classification.

Stability

Formal stability is the sense of tension vs. calmness in a portion of music. A relative sense of stability in a work is a common means of delineating form, and it is an important dramatic concern for creating momentum and engaging a listener’s expectations about what might happen, given their familiarity with how other pieces in a given genre/style behave.

Common features for each might include some combination of the following, among others:

-

- Stability: relatively less change, consistent or decreasing dynamic level, tonic expansions, regular hypermeter, no modulation, diatonic melody, and diatonic harmony

- Instability: relatively more change, increasing dynamic level, extreme registers, increased chromaticism (tonicization), increased rhythmic activity, modulation, sustained dominant, sequences (especially chromatic ones), irregular hypermeter, and irregular phrase lengths

Because it’s statistically common for works to start with a stable section, an unstable contrasting section would likely sound unusual at the beginning of a work.

Terminology

In terms of form in general, the first contrasting section is labeled B, and each subsequent new section receives the next letter of the alphabet (C, D, E, etc.).Within a known form, contrasting sections go by many names, including but not limited to:

- Stable

- Unstable

Auxiliary Formal Sections

In addition to the core sections of a work, other sections may introduce, follow, or come between these core sections. These sections are called auxiliary sections, and there are two general categories: external and connective.

External Auxiliary Sections

External auxiliary sections either introduce a piece/section (prefix) or follow the generic conclusion of the piece or section (suffix). Prefixes and suffixes come in small and large varieties.

Prefix

A prefix (Rothstein 1989) refers to music that comes before the generic start of a phrase or piece and tends to express a formal sense of “before the beginning.” A prefix can be described as either small or large depending on whether or not it contains a complete phrase. Large prefixes contain at least one phrase, while small prefixes don’t have complete phrases and are typically far less noticeable. Small prefixes are often nothing more than the accompaniment for a section starting before the melody begins, and they may precede any phrase in a work.

The most common type of large prefix is called an introduction. Introductions are often in a slower tempo than the rest of the work and often contain their own thematic material. Small prefixes can be found in works of most genres and eras, but large prefixes are less ubiquitous and tend to show up more often in particular genres, like the opening of a symphony. However, other genres like the piano sonata (Beethoven’s “Das Lebewohl,” Op. 81a), string quartet (Mozart’s “Dissonance” quartet), and dance forms like ragtime (Joplin, “The Entertainer”) can contain them as well.

Below are some examples:

- Small Prefix:

- Chopin’s Polonaise in C minor, Op. 40, no. 2 – First two measures

- Kiesza’s “Dearly Beloved” – Opening

- Large Prefix:

- Introduction of the 1st movement of Mozart’s “Dissonance” string quartet in C major (K. 465) – The whole movement is about 10 minutes long, and its slow introduction (large prefix) lasts for nearly two minutes until the sonata form proper starts. There is a stark tempo change from slow to fast at 1:59 that makes the boundary clear.

- Joplin’s “The Entertainer” – First four measures

- Madonna’s “Vogue” – This large prefix has many subsections (0:00, 0:34, 0:50), but the song proper doesn’t start until she begins singing at 1:07.

Suffix

A suffix (Rothstein 1989) refers to music that comes after the close of a phrase or piece and tends to express a formal sense of “after the end.” The distinction between large and small again concerns whether or not it contains a complete phrase. Small suffixes can be found after the close of any phrase, but the affect is quite different depending on the type of cadence they follow. After an authentic cadence, they typically project a sense of stability and closure, but after half cadences, they tend to prepare for the entrance of the upcoming section and therefore project a sense of instability. Though possible after any phrase, large suffixes typically appear in two specific locations: (1) at the very end of a piece in the form of a coda, and (2) as the closing section of a sonata form’s exposition and recapitulation (see Sonata Form). In most cases, a suffix contains musical material that is different from the phrase it follows, though that material may be derived from an earlier phrase.

Below are some examples:

- Small Suffix:

- Dove Shack’s “Summertime in the LBC” – After the final chorus, a small suffix (in the form of a simple accompaniment) ends the song as it fades out from 3:41 until the end.

- Bizet, Habanera from Carmen – The B section ends just after the singer sustains a high note and cadences with the orchestra immediately after (cadence is at 2:01). After this cadence, the orchestra just repeats an accompanimental pattern a few times. The music from 2:01-2:06 is the small suffix.

- Large Suffix:

- Puccini, “O Mio Babbino Caro” from Gianni Schicchi – Ending: You can hear the formal ending of the aria at 1:48 with the line “O Dio, vorrei morir!” at which time the aria could have ended satisfactorily. However, an elision occurs with the strings, which play the main melody (a.k.a. ritornello) after the soloist finishes her line. Notice that the music from 1:48 to the end projects a sense of stability, as suffixes tend to do when they follow an authentic cadence.

- End of the 1st movement of Mozart’s “Dissonance” string quartet in C major (K. 465) – This movement ends with a coda at 9:58 (large suffix at the very end of a piece). Notice that it starts after the material from the closing section of the recapitulation comes to an end. You can compare the very end of the exposition (6:12) to the very end of the recapitulation (9:28) to hear how this large suffix is added material that was not in the exposition (even though many of its motives and ideas have been heard before).

- Brahms’s Intermezzo in A major, op. 118, no. 2 – This work is in ternary form. The A section ends at 1:28 and is followed by a suffix from then until before the B section starts at 1:57.

Connective Auxiliary Sections

Transition

Generally, a transition is a section of music that functions to connect two core sections. Transitions usually help to lead away from the piece’s main section toward a contrasting section. In particular, a transition comes between two sections where the upcoming section is not the initiation of a large-scale return (i.e., between A and B, not between B and A). Often a modulation is introduced to help prepare a section in a new key, though it is not required. A transition also plays a role in the balance of stability and instability in a work. Core sections of a work are very often stable thematic statements (relatively), but transitions typically introduce instability (and a gain in energy), which will likely be countered by the stability of the section that follows.

Like suffixes and prefixes, transitions and retransitions (discussed further below) come in “large” and “small” varieties. A transition can be described as either small or large depending on whether or not it contains a complete phrase. Large transitions contain at least one phrase, while small transitions don’t have complete phrases and are typically far less noticeable.

Near their end, transitions (and retransitions) often drive toward attaining the dominant chord of the upcoming key. Often, a suffix will begin once the dominant has been attained in a situation sometimes called “standing on the dominant” (William Caplin) or “dominant lock” (James Hepokoski and Warren Darcy).

A transition may have a clear stopping point before the next section starts, or there may be a single melodic line that fills the space between it and the upcoming section (caesura fill), or the transition my end at the onset of the new section with an elision. In more vague cases, the end of the transition and the start of the new section may be hard to pinpoint, but it is still clear that it must have happened during a particular span of time.

Transitions are commonly found in sonata forms between the primary and secondary themes and in rondo forms between the A section (refrain) and a contrasting section (episode). Small transitions are often found in ternary forms to connect the A and B sections.

Below are some examples:

- Large Transition:

- Mozart’s piano sonata in B♭ major, K. 333, 1st – This work is in sonata form. The transition between the primary theme and the secondary theme occurs between 0:20 and 0:42.

Retransition

A retransition is very similar to a transition, but its location and function are different. Retransitions come between two sections where the upcoming section is the initiation of a large-scale return (i.e., between B and A, not between A and B). In most cases, retransitions help to prepare the return of the piece’s main section: the return of the A section in ternary or rondo form, or the restatement of the primary theme at the onset of the recapitulation in sonata form. A retransition often drives toward attaining the dominant chord of the home key and will often prolong the dominant once attained, usually in the form of a suffix. Retransitions may have a clear half-cadential ending (possibly followed by a suffix), or they may have an elided ending that coincides with the initiation of the following section.

Below are some examples:

- Small Retransition:

- Chopin’s Polonaise in C minor, Op. 40, no. 2 – This work is in compound ternary form. In the first, large A section of the overall ABA form, there is a small retransition between B and A from 2:35 to 2:39. It is only one measure long.

- Handel’s aria “Lascia ch’io pianga” from Rinaldo – This work is in five-part rondo form (ABACA). There is a very short, small retransition between the B and A sections from 1:41 to 1:44.

- Large Retransition:

- Mozart’s piano sonata in B♭ major, K. 333, 1st – This work is in sonata form. The retransition between the development and the recapitulation occurs between 4:29 and 4:45.

- Brahms’s Intermezzo in A major, Op. 118, no. 2 – This work is in ternary form. There is a retransition between the B section and the final A section from 3:08 to 3:19.

- Rothstein, William. 1989. Phrase Rhythm in Tonal Music. New York: Schirmer.

- Summach, Jason. 2012. “Form in Top-20 Rock Music, 1955–89.” PhD diss., Yale University.

- This particular dichotomy was introduced by Jay Summach (2012). ↵

Core sections comprise the main musical and poetic content of a song. Core sections include strophe (AABA and strophic form only), bridge, verse, chorus, prechorus, and postchorus.

Auxiliary sections help frame the core sections: introducing them, providing temporary relief from them, or winding down from them.

The primary theme of a rondo-form work, typically stated at the beginning, after each contrasting episode, and as the last section (though a coda may follow).

A core section of a popular song that is lyric-invariant and contains the primary lyrical material of the song. Chorus function is also typified by heightened musical intensity relative to the verse. Chorus sections are distinct from refrains, which are contained within a section.

A basic multi-phrase unit. In pop music, a strophe is a focal module within strophic-form and AABA-form songs.

The process of becoming is an analytical phenomenon that captures an in-time, analytical reinterpretation regarding a formal/phrasal unit's function, abbreviated with a rightward double arrow symbol (⇒). Examples include primary theme ⇒ transition, continuation ⇒ cadential, or suffix ⇒ transition.

Groupings of measures into different patterns of accentuation akin to meter. A hypermeasure is typically four measures long.

A change of key.

A pattern that is repeated and transposed by some consistent interval. A sequence may occur in the melody, the harmony, or both.

A term used when describing the sections of a rondo form that are not the main theme (a.k.a. A or refrain). Episodes provide contrast with the main theme through changes in multiple domains, primarily key and melodic/rhythmic/harmonic material.

Sections that are lyric-variant and often contain lyrics that advance the narrative.

A type of contrasting section that tends to function transitionally in the formal cycle. Bridges tend to emphasize non-tonic harmonies and commonly end on dominant harmony.

A formal category including both main sections (e.g., A, primary theme, refrain) and contrasting sections (e.g., B, C, D, secondary theme, episode, contrasting middle, development, digression). In contrast to auxiliary sections, core sections present the main musical material of a work and generally represent the bulk of a composition.

An external expansion that occurs before the beginning of a phrase. Prefixes are usually introductions, and they may be small, as when the accompaniment for a lied begins before the singer, or they may be large, as when a symphony begins with a slow introduction.

A type of external expansion that occurs after the end of a phrase. There are three terms commonly used to describe suffixes, ranging in size from smaller to larger: post-cadential extension, codetta, and coda.

A relatively complete musical thought that exhibits trajectory toward a goal (often a cadence).

A section of music that occurs before the start of the first core section.

A large suffix section occurring at the end of a work (or end of a movement within a multi-movement work), after the PAC that ends the piece’s core sections.

A retransition is very similar to a transition, but retransitions lead to a return to the main section in the tonic key, while transitions move away from tonic. Retransitions may have a clear half-cadential ending (possibly followed by a suffix), or they may have an elided ending that coincides with the initiation of the following section.

A category of chords that provides a sense of urgency to resolve toward the tonic chord, including V and vii° (in minor: V and vii°).

The overlapping of two phrases, functioning as the ending of one phrase and the simultaneous beginning of the next.