I. Fundamentals

21 Texture

Samuel Brady and Mark Gotham

Key Takeaways

- Musical texture is the density of and interaction between a work’s different voices.

- Monophony is characterized by an unaccompanied melodic line.

- Heterophony is characterized by multiple variants of a single melodic line heard simultaneously.

- Homophony is characterized by multiple voices harmonically moving together at the same pace.

- Polyphony is characterized by multiple voices with separate melodic lines and rhythms.

- Most music does not conform to a single texture; rather, it can move between them.

Texture is an important (and sometimes overlooked) aspect of music. There are many types of musical texture, but the four main categories used by music scholars are monophony, heterophony, homophony, and polyphony.

Monophony

A monophonic texture is characterized by a single unaccompanied melodic line of music. Monophony involves all instruments playing or singing in unison, making it the simplest and most exposed of all musical textures. The first movement of Cello Suite no. 1 in G Major (1717) by Johann Sebastian Bach is an example of a monophonic texture. Notice how the solo cello line is the only voice in this work.

Example 1. Cello Suite no. 1 in G Major, I. Prelude, (BWV 1007) by Johann Sebastian Bach, performed by Yo-Yo Ma.

Now let’s listen to “Where Have All the Flowers Gone?” (1955) by Pete Seeger. Note that Seeger’s voice is the only musical line; therefore, this work is a second example of monophony.

Example 2. “Where Have All the Flowers Gone?” by Pete Seeger.

Heterophony

A heterophonic texture is characterized by multiple variations of the same melodic line that are heard simultaneously across different voices. These variations can range from small embellishing tones to longer runs in a single voice, as long as the melodic material stays relatively constant.

Listen to “Ana Hasreti” (2001) by Göskel Baktagir, an example of Turkish classical music. Notice how the winds embellish the melody presented by the plucked strings. While the instruments play different embellishments, they present essentially the same melodic material.

Example 3. “Ana Hasreti” (2001) by Göskel Baktagir.

Now listen to the traditional Irish reel “The Wind That Shakes the Barley,” recorded by the Chieftains in 1978 (beginning at 0:50), and notice the slight variation between the melodic lines of the fiddle (violin) and the flute. This slight variation between the violin and flute presents a second example of heterophony.

Example 4. “The Wind That Shakes The Barley/The Reel With The Beryle” by The Chieftains; listen starting at 0:50.

Homophony

A homophonic texture is characterized by having multiple voices moving together harmonically at the same pace. This is a very common texture. Many times, this takes the form of having a single melody that predominates, while other voices are used to fill out the harmonies. Homophony is sometimes further divided into two subcategories, homorhythm and melody and accompaniment.

Homorhythm

Homorhythm is a type of homophonic texture in which all voices move in an extremely similar or completely unison rhythm. This is most often seen in chorale-like compositions, where the melody and harmonies move together in block chords.

Let’s listen to Six Horn Quartets: no. 6, Chorale (1910), written by Nikolai Tcherepnin. Notice how both the melody and harmony move mostly in block chords, creating a unified rhythm.

Example 5. Six Horn Quartets: no 6, Chorale by Nikolai Tcherepnin, performed by the Deutsches Horn Ensemble.

Now let’s listen to the folk song “Wild Mountain Thyme” recorded by The Longest Johns in 2018 (0:20–0:44). Remember that in a homorhythmic texture, there is a similarity of rhythm throughout all of the voices. In this example, there is a melody that stands out from the texture, but the voices still move in rhythmic unison.

Example 6. “Wild Mountain Thyme,” by The Longest Johns; listen from 0:20–0:44.

Melody and Accompaniment

A melody and accompaniment texture is perhaps the most common type of homophony. This texture is characterized by a clear melody that is distinct from other supporting voices, which are called an accompaniment. Often the melody will have a different rhythm from the supporting voice(s).

Let’s listen to the second movement of Paul Hindemith’s Flute Sonata (1936). This example features a very clear melody (flute) and accompaniment (piano). Notice how the piano is never completely in rhythmic unison with the flute; however, it provides the role of accompaniment by filling out the texture harmonically.

Example 7. Flute Sonata by Paul Hindemith, performed by Emmanuel Pahud and Eric Le Sage.

Now let’s listen to “Misty” (1954), written by Erroll Garner and performed by Ella Fitzgerald. Notice how the piano accompanies the primary melody sung by Fitzgerald (the vocalist).

Example 8. “Misty” (1954), written by Erroll Garner and performed by Ella Fitzgerald.

Polyphony

Polyphony is characterized by multiple voices with separate melodic lines and rhythms. In other words, each voice has its own independent melodic line, and the independent voices blend together to create harmonies.

In Western classical music, polyphony is commonly heard in fugues, such as Fugue no. 5 in D Major (1951–1952), written by Dmitri Shostakovich. Notice how each individual melodic line is independent, yet the voices create harmonies overall when heard together.

Example 9. Fugue no. 5 in D Major by Dmitri Shostakovich, performed by Joachim Kwetzinsky.

This can also be heard in the final chorus of “I’ll Cover You – Reprise” from the Broadway musical Rent (1996), written by Jonathan Larson (2:20–2:45). Notice how there are three independent vocal layers, singing different melodies and rhythms, but working together to create new harmonies overall:

Example 10. “I’ll Cover You – Reprise” from the Broadway musical Rent (1996), written by Jonathan Larson; listen from 2:20–2:45.

Most musical works have some variety in texture. For example, you may have heard a work that opened with a solo voice or instrument, then changed to a melody with accompaniment. There are many different possibilities!

- Terms That Describe Texture (Lumen)

- Texture in Music (Hello Music Theory)

- Texture in Music (learnmusictheory.net)

- Texture (Emory University)

- Texture (Robert Hutchinson)

- Texture (Phillip Magnuson)

- Four Types of Texture in Music (perennialmusicandarts.com)

- Interactive Musical Textures Worksheet (website, website)

- Study Guide to Texture and Worksheet (.pdf)

- Texture: Homophonic or Polyphonic? (website)

- Texture Composition Assignment, pp. 17–22 (.pdf)

- Identifying Textures (.pdf, .docx) Worksheet playlist

.front-matter h6 {

font-size: 1.25em;

}

.textbox--sidebar {

float: right;

margin: 1em 0 1em 1em;

max-width: 45%;

}

.textbox.textbox--key-takeaways .textbox__header p {

font: sans-serif !important;

font-weight: bold;

text-transform: uppercase;

font-style: normal;

font-size: large;

}

a:link {

text-decoration: none;

}

.button {

background-color: ivory;

color: purple;

}

div.part-title {

color: var(--primary);

font: 700 1.25rem "FreeSans", sans-serif;

text-size: x-large;

text-transform: uppercase !important;

}

Chromatic Modulation Using Enharmonically Reinterpreted Diminished-Seventh Chords

Diminished-seventh chords can also be respelled for the purposes of modulating to distant keys. Each diminished-seventh chord can be respelled such that any of the its four notes is the root, and thus, can be resolved to any of four different target chords.

- Coming soon!

Key Takeaways

- much rarer than the other three triad types (major, minor, and diminished).

- interesting for several reasons including

-

- that rarity itself, and

- the symmetrical construction, which creates potential flexibility and ambiguity (just like with the diminished seventh chord)

- most often seen in one of two forms:

- as III+ in harmonic minor (this being the only form in the major/minor system without chromatic alteration), and

- as a chromatic passing chord between V and I in a major key: V, V+, I.

-

Aren’t we forgetting something here? We’re now well into chromatic harmony, yet we’ve hardly mentioned one of the four types of ostensibly diatonic triads: we’re up to speed with augmented sixth chords, but not the augmented triad. So what is this augmented triad all about? How do composers use it? How have we neglected it so long (and why do so many textbooks brush over it altogether)?

Recall that we have four types of triads that can be constructed with major and minor thirds alone:

- Diminished triad (minor third + minor third)

- Minor triad (minor third + major third)

- Major triad (major third + minor third)

- Augmented triad (major third + major third)

So the augmented triad is part of this set of possibilities, but apparently not an equal member, at least not in the eyes of common practice composers. Clearly major and minor triads are mission critical to tonal music, and so is the diminished triad, especially in its dominant function role (as viio and as a part of V7). The augmented triad is a slightly peripheral character in relation to those protagonists.

Always Chromatic?

Part of that rarity has to do with the structure of the major/minor system itself: III+ in harmonic minor is the only time the augmented triad appears in the major/minor system without chromatic alteration. This III+ triad is closely related to both the dominant (V) and minor tonic (i): in both cases, two scale degrees are held common and only one semitone distinguishes the chord tone which changes:

- III+ and V: [latex]\hat5[/latex] and [latex]\hat7[/latex] in common, semitone between [latex]\hat2[/latex] and [latex]\hat3[/latex];

- III+ and i: [latex]\hat3[/latex] and [latex]\hat5[/latex] in common, semitone between [latex]\hat1[/latex] and [latex]\hat7[/latex].

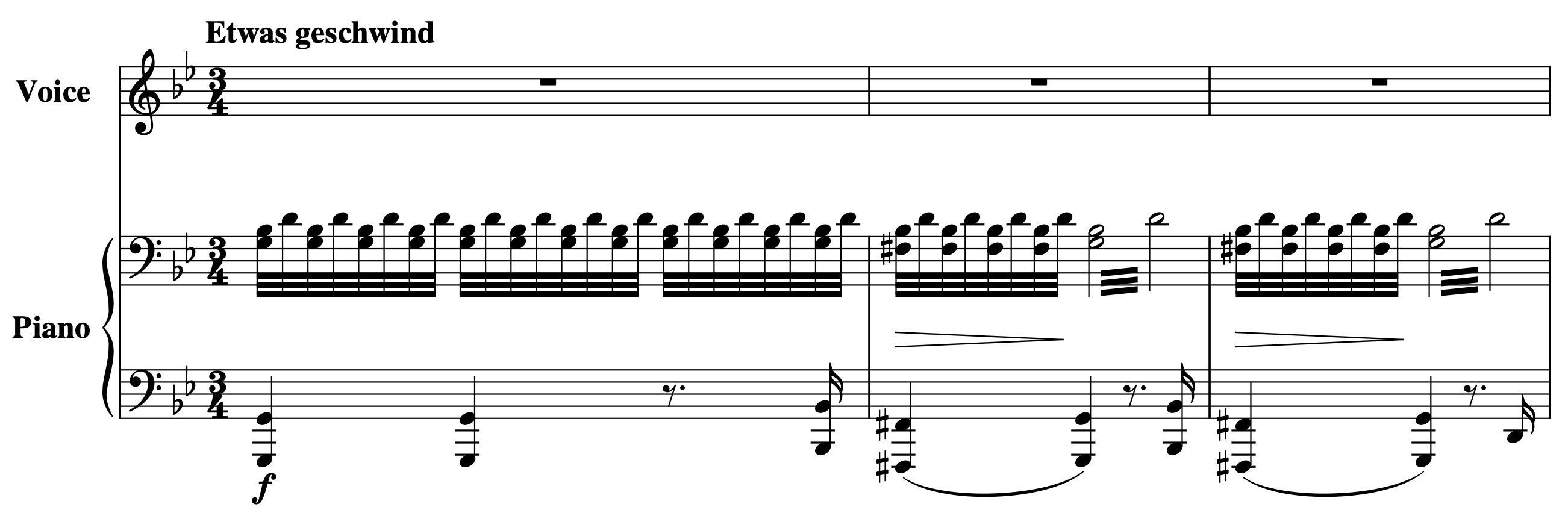

Overall, I'd say that the sound and usage of III+ typically suggests a dominant function. See what you think of the following example from the opening of Schubert's "Der Atlas" (Example 1) in which:

- B♭ and D remain constant throughout ([latex]\hat3[/latex] and [latex]\hat5[/latex]).

- G moves to F♯ and back ([latex]\hat1[/latex] and [latex]\hat7[/latex]).

- This arguably gives the impression of a tonic-dominant alternation, but with very slight changes.

Here is the entire song:

Schwanengesang, D.957 by OpenScore Lieder

The small steps between these chords relate to a key part of the "parsimonious voice leading" that’s so important to the "Neo-Riemannian" approach to harmony, which seeks to account for the extended tonal relations that become more common in the late 19th century. For more on that, see Neo-Riemannian Triadic Progressions. For now, let’s continue to look at some examples of the augmented triad in practice.

Rarely focal

The relatively peripheral role and the rarity of augmented triads may be thought to diminish its importance, though as the price of gold, diamond, and other rare commodities attest, that very rarity can be valuable. For Schoenberg, this makes the augmented triad "better protected against banality" than the diminished triad and seventh (1911, trans. ed. 1983, p. 239).

The idea of rarity also needs unpacking: when we speak of "rarity" in harmony, we usually mean that it is unusual to see that chord in a focal role. This speaks to Richard Cohn’s observation that "when an augmented triad appears in music before 1830, its behavior is normally well regulated and unobtrusive, tucked into the middle of a phrase rather than exposed at its boundaries, passed through quickly and lacking metric accent" (2012, p. 43).

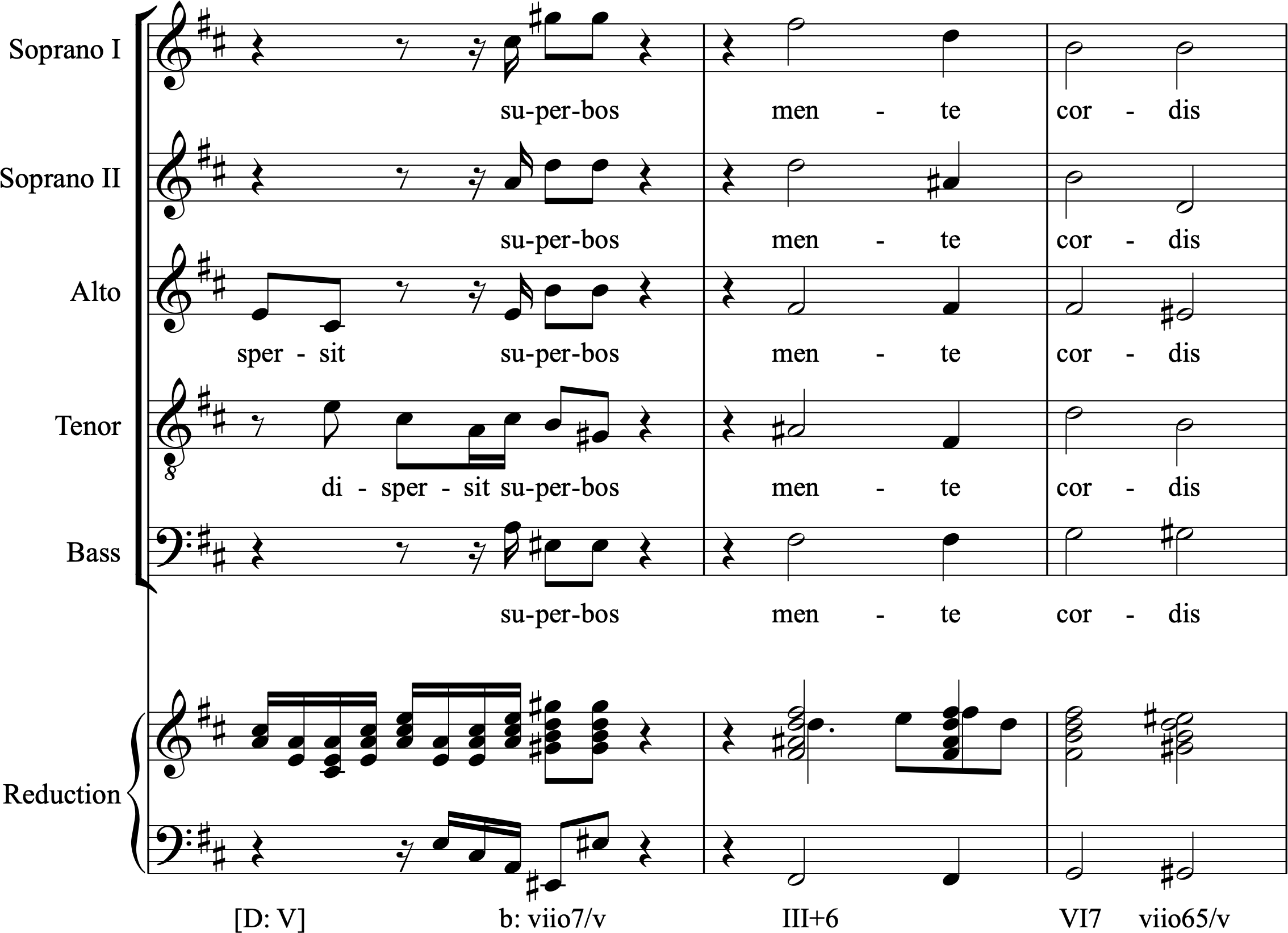

This may be true in the general case, though that’s not to say there aren’t glorious counterexamples. Example 2 sets out such an example from the "mente cordis" section that concludes the "Fecit Potentiam" of Bach’s Magnificat (1723, 1733). This is a remarkable moment: not only is there an augmented triad at all, but it is introduced by nearly full forces, spanning the full register, and after a dramatic general pause which itself is preceded by a diminished seventh. You couldn’t hope to find a clearer, more dramatically foregrounded augmented triad in any repertoire.

Chromatic passing chord

Although there is only one diatonic form of the augmented triad (III+ in minor), there are clearly many more possibilities when we expand the remit to include chromatic alterations. Here too, however, some are more common than others. A particularly favored use sees the augmented chord as part of a chromatic passing motion from V to I in major, with the whole-tone step from [latex]\hat2[/latex] to [latex]\hat3[/latex] "filled in" with a chromatic semitone motion that gives a fleeing . This can appear in several ways:

- As a straightforward V–V+–I

- With another harmony on the initial [latex]\hat2[/latex]: e.g., ii–V+–I

- With or without sevenths: e.g., ii7–V+7–I

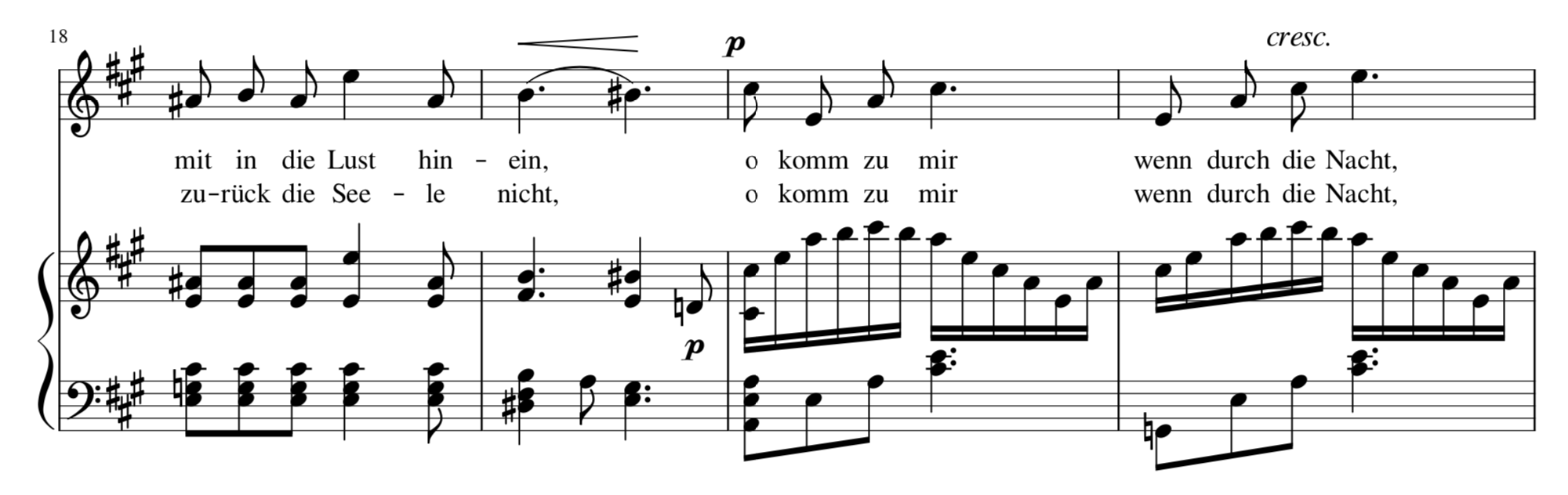

Example 3, from Fanny Mendelssohn Hensel's Gondellied (6 Lieder, Op. 1, no. 6), sets this out. Measures 19–20 can be seen as a V6/V–V+–I cadence in A (or, with sevenths, V[latex]\mathrm{^6_5}[/latex]/V–V+7–I) where:

- the augmented chord appears in a dominant function;

- the crucial note of that augmented chord (B♯) is the raised supertonic, arising through chromatic motion from [latex]\hat2[/latex] to [latex]\hat3[/latex] (both in the voice part and doubled in the piano).

Here is the entire song:

Hensel, Fanny (Mendelssohn) - 6 Lieder, Op.1, No.6 - Gondellied by OpenScore LiederCorpus

The Augmented Triad as Figure or Ground in Liszt’s R. W. Venezia

So far, we have seen examples of the augmented triad in diatonic form (III+), and as a chromatic alteration but with a clearly defined function (V+). Let's now venture further into the chromatic territory and to pieces which use the augmented triad in a prominent, focal way. Liszt’s late music includes some fascinating miniatures, many of which heavily emphasize the augmented triad.[1] R.W. Venezia is one such work, highlighting the augmented chord in general, and C♯ augmented [C♯, F, A] in particular. This chord receives such a weighting that it stakes a remarkable claim to a kind of overall primacy or tonicity that at least challenges and perhaps even vanquishes the corresponding claim from a tonal center (B♭).

Cohn (2012, 47), after Harrison (1994, 75ff.), discusses a similar emphasis of the diminished chord in Schubert’s "Die Stadt," rightly observing that "rhetorical garments normally reserved for consonances" are used in this repertoire to afford dissonant chords a kind of surrogate tonic status (see also Morgan 1976). Those rhetorical strategies are well summarized by the pithy notion of "first, last, loudest, longest."

R.W. Venezia begins with a C♯ augmented chord outlining, resolving by parsimonious voice leading to B♭ minor as the start of a rising chromatic sequence which ultimately turns into a long succession of rising (initially parallel augmented) triads that climax in a blazing, forte B♭ major. That forte section then moves through more parsimonious voice leading cycles before returning to C♯ augmented, now fortissimo. Finally, this C♯ augmented chord initiates a descent which deftly combines the pitches of B♭ minor and C♯ augmented [B♭, C♯, F, A], leading to an ambiguous close on a unison C♯. That final C♯ is repeated, carrying with it the ambiguity right up to the last note. If the second, final C♯ were a B♭, then the piece would come down more firmly in favor of B♭ minor. As it is, Liszt maintains the delicate balance and leaves us wondering which is the figure and which the ground.

In short, C♯ comes "first" and "last," while B-flat probably wins in the "loudest" stakes, leaving "longest" as the primary vehicle of ambiguity. The augmented chord is used considerably more than the average for the time, even for Liszt (a considerably above-average user), though still not to the same extent as major or minor triads. Then again, the C♯ augmented triad specifically is used to approximately the same extent as B♭ major and minor combined, raising the case for it as "tonic." Whether that is enough is open to debate; ultimately, I hear them in an amazingly effective balance where neither quite shines through.

Anthology Examples

This chapter has surveyed some claims about how relatively common or otherwise specific particular progressions are. But so far, we've just looked at examples. To make sense of this kind of claim, we ought to consider the overall case. We don’t have space here to go into that in detail, but this final section provides some direction toward extensive lists of further examples for you to explore.

First, here is an initial list of approximately 200 examples gathered from the literature. The list could be thought of as an augmented triad "canon"—those instances notable enough to have been mentioned in either the theoretical or historical literature. These repertoire occurrences are varied in function and tone. Many are indeed "merely" incidental appoggiaturas and decorations, while others are fundamental, referential sonorities; some are isolated cases, others are a core part of wider, recurring harmonic processes; some have an ambiguous role, others have a clear musical and even extra-musical meaning including topical associations which generally center on death, ambivalence, or mystery.[2]

Second, head to the Harmony Anthology chapter for a list of moments in the OpenScore Lieder collection that analysts have viewed in terms of augmented chords. The list is sortable by composer, collection, song, measure, Roman numeral (figure) and key. Each entry includes a link to the score.

- Head to the section on augmented chords in the Harmony Anthology chapter and pick one (or more) of the repertoire examples listed in which an analyst has identified the use of an augmented chord.

- For that passage, make a Roman numeral analysis of the measure in question and one or two on either side (enough to establish a chord progression and some context).

- Create one such harmonic analysis including the augmented triad provided (figure and key are given in the table).

- If you disagree with that reading (as you may well do), then provide an alternative harmonic analysis without it.

- Do step 1 for several cases and identify any that seem similar to each other, and to the above. For instance, for the cases given as V+ in the anthology, are many of them similar to the chromatic passing motion in the Hensel above? Can you find any dramatic examples like the Bach? Do you see any other recurring practices not described in this chapter?

Key Takeaways

- Diatonic sequences repeat musical segments and are transposed in a regular pattern within a key.

- Chromaticized diatonic sequences include can include chromatic embellishments or chromatic chords, such as applied (secondary) dominants. These sequences avoid strict transposition of both interval size and quality.

- Chromatic sequences differ from diatonic sequences in that both the size and quality of the interval of transposition is maintained throughout the sequence. Diatonic sequences preserve the interval size, but not the quality, to ensure that they stay within a single key.

- Remember, with all sequences, the voice leading must be consistent within every voice. Chord voicings should match between all corresponding components.

Descending-Fifths Sequence

Consider the following two-chord sequence (Example 1), often referred to as the "descending-fifths sequence."

Example 1. A diatonic descending-fifths sequence.

The sequence model, a root progression by descending fifth, is transposed down by second in each subsequent copy of the model. Because the sequence uses chords entirely from the key of G major, the root progressions don't match exactly throughout the sequence. For example, the root progression between the IV and viio chords is an augmented fourth, whereas the root progressions between every other pair of chords is either a perfect fifth or perfect fourth. We "cheat" in the sequence in this way in order to keep the music within a single key. If the interval between successive chord roots was consistently a perfect fifth/fourth, the root progression would be as follows: G–C–F–B♭–E♭–A♭–D♭… and so on. The sequence would rather quickly bring the music outside of the key of G major, and into new chromatic territory. It would become a chromatic sequence.

Chromatic sequences differ from their diatonic counterparts in a few important ways:

- The chords that initiate the sequence model and each successive copy contain altered scale degrees.

- The chords within the pattern are of the same quality and type as those within each successive copy of that pattern.

- The sequences derive from those that divide the octave equally.

Importantly, chromatic sequences are not merely sequences that contain chromatic pitches. Example 2 shows the same descending-fifths sequence, this time with alternating secondary dominant chords. While the sequence contains chromatic chords (the secondary dominants), it is not a truly chromatic sequence because the overall trajectory of the sequence is still one that traverses the scale steps of a single key. Notice that the progression of chord roots on successive downbeats still matches the purely diatonic sequence shown in Example 1: G–F♯–E–D.

Example 2. A diatonic descending-fifths sequence with alternating secondary dominant-seventh chords.

Conversely, we can create a truly chromatic sequence if we ensure that the progression of chord roots maintains a consistent pattern of intervals throughout the sequence. An easy way to do this is to make the second chord of the sequence model into a dominant-seventh chord that can be applied to the first chord of the subsequent copy of the model. In Example 3, the second chord of the model is now F7 instead of a diatonic IV chord. We interpret this as V7 of the chord that follows, which is, in turn, another dominant-seventh chord.

Example 3. A chromatic descending-fifths sequence with interlocking secondary dominant-seventh chords.

The voice leading in the above sequence requires some attention. Because every chord is interpreted as a dominant-seventh of the chord that follows, it is not possible to resolve both the leading tone and the chordal seventh as normal. As is the case whenever you connect seventh chords with roots a fifth apart, the voice leading requires an elided resolution. Instead of the chord you expect to hear following a dominant-seventh chord, you get a dominant-seventh chord with the same chord root. For example, we expect to hear either a C or Cm chord following a G7 chord. An elided resolution would result in a C7 chord in place of the expected chord. An example of an elided resolution is shown in Example 4. The example shows the expected C resolution in parentheses. The elided resolution essentially "elides" the chord we expect with the following chord, C7. In a sense, we mentally skip over the expected chord to get to the next dominant-seventh chord. An important result of the elision is that the leading tone of the first dominant-seventh chord, B, resolves down by half step to become the new chordal seventh. Likewise, when the chordal seventh in the first dominant-seventh chord, F, resolves down by half step, it becomes the new leading tone. This leading tone/chordal seventh exchange is essential for proper voice leading in chord progressions that use interlocking seventh chords, such as the sequence above. Furthermore, this kind of voice leading is integral to the study of jazz harmony, as you will find in other parts of this textbook.

Example 4. An elided resolution of a dominant-seventh chord.

Returning to Example 3, notice that the progression of chord roots on each successive strong beat divides the octave equally into major seconds. This results in a sense of tonal ambiguity, making the Roman numeral analysis of these chords tenuous, at best. In particular, the chords identified with asterisks in the example are only labeled as such for consistency. In many cases, when analyzing highly chromatic music, it is often quite difficult to assign Roman numerals to chords; this tonal ambiguity is part of the aesthetic of this kind of music. In cases like this, it is often convenient to also analyze the music using lead-sheet symbols. These have been included in the examples in this chapter.

Ascending 5–6 Sequence

Example 5. A diatonic ascending 5–6 sequence.

Example 6. A chromaticized diatonic ascending 5–6 sequence, featuring secondary dominant chords.

The above examples present the diatonic ascending 5–6 sequence (Example 5) and its chromaticized variant (Example 6). Note that both of these include an inconsistent pattern of intervals between chord roots in the second measure. To that point, the pattern of chord roots was a descending minor third followed by an ascending perfect fourth. From beat 1 to beat 2 in m. 2, the chord roots are D to B♭—a major third. To make this a truly chromatic sequence, this interval must be corrected to match the others. Thus, we would change the B♭7 to a B7. Likewise, we would then change the chord that follows the B7 to a chord with a root of E (rather than E♭), to preserve the root progression by perfect fourth (Example 7).

Example 7. A chromatic ascending step sequence, featuring secondary dominant chords.

A similar problem arises with the chord qualities used at the beginning of each subsequent copy of the sequence model. The first chord of the sequence is major, so for it to be a chromatic sequence, we must change the remaining first chords of each iteration to be major as well. The final result is a sequence in which the chord on every strong beat is a major triad with roots a major second apart. If it were to traverse the entire octave, the sequence would divide the octave into major seconds. In Example 7, though, the sequence stops once it reaches the E major triad, treats that triad as a dominant chord, and modulates into A major. The modulation brings the music down a half step from its starting key. Distant modulations such as these are one of the reasons that chromatic sequences can be powerful tools.

Descending 5–6 Sequence

Example 8. A diatonic descending thirds sequence.

Example 9. A chromatic descending 5–6 sequence that modulates from D major to C major.

Example 10. A chromatic descending 5–6 sequence using inverted chords on every weak beat. The sequence outlines the whole-tone scale on every strong beat.

The familiar "Pachelbel" sequence (Example 8) can derive a chromatic sequence in a couple of ways. The diatonic version of this sequence alternates root motion by perfect fourth with either major or minor seconds. The fully chromatic version of this sequence replaces the root motion by second with root motion by minor third (Example 9). This version of the sequence traverses the octave by major seconds, outlining the whole-tone scale and creating a strong sense of harmonic ambiguity by its end. When you listen to Example 10, for instance, notice that the D major chord that finishes the sequence hardly sounds like the tonic, even though, nominally, it is. This version of the sequence also uses inverted chords on every weak beat, creating a bass line that descends through the chromatic scale.

- Coming soon!