Richard V. Goodwin

University of Otago, goodwin.richard@gmail.com

Recommended Citation

Goodwin, Richard V. (2018) “An Old Film in a New Light: Lighting as the Key to Johannine Identity in “Ordet”,” Journal of Religion & Film: Vol. 22: Iss. 2, Article 2. Available at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/jrf/vol22/iss2/2

This article is brought to you open access by Pressbooks at University of Nebraska at Omaha Criss Library.

“Lighting was [Dreyer’s] great gift and he did it with expertise,” said Birgitte Federspiel, the actress who played Inger in Ordet (Carl Theodor Dreyer, 1955). “He shaped light artistically like a sculptor or painter would.” [1] Despite Dreyer’s mastery of lighting, however, comparatively little attention has been paid to the use of light in Ordet,[2] a cinematic tour de force that ranks among the Danish auteur’s greatest works.[3] This neglect perhaps comes as no surprise, at least with respect to religion and film as a discipline. Scholars in the field have noted the discipline’s tendency to overlook audiovisual elements of cinema in favour of discursive elements.4 Have we missed anything by overlooking the role of light? What do we learn by attending to it? I argue that by paying attention to the lighting and to light language in the film, we arrive at an interpretation in which the protagonist, Johannes (Preben Lerdorff Rye), is understood to be a stand-in for John the Baptist. Such an interpretation uncovers new layers of meaning, including the possibility that the depiction of Johannes symbolizes Kaj Munk, the author of the original work upon which the film is based. As such, this study underscores the value for religion and film in engaging in formal analysis rather than attending exclusively to narrative.

Biblical Antecedents for Johannes

In his excellent essay on Ordet, film historian P. Adams Sitney makes a fascinating observation regarding the identity of the film’s protagonist, Johannes. Sitney’s insight pertains to the scene in which Johannes flees his home. For those unfamiliar with the film, Ordet tells the story of the Borgens, an early-twentieth century Danish family straining under the weight of religious doubts in the midst of tragedy. One of the Borgen sons, Johannes, is under the delusion that he is Jesus Christ. Inger (Birgitte Federspiel), the wife of another Borgen son, dies in childbirth but, at the finale, is miraculously resurrected by Johannes, now cured of his messianic fantasy, thereby removing all religious doubts and healing all rifts.

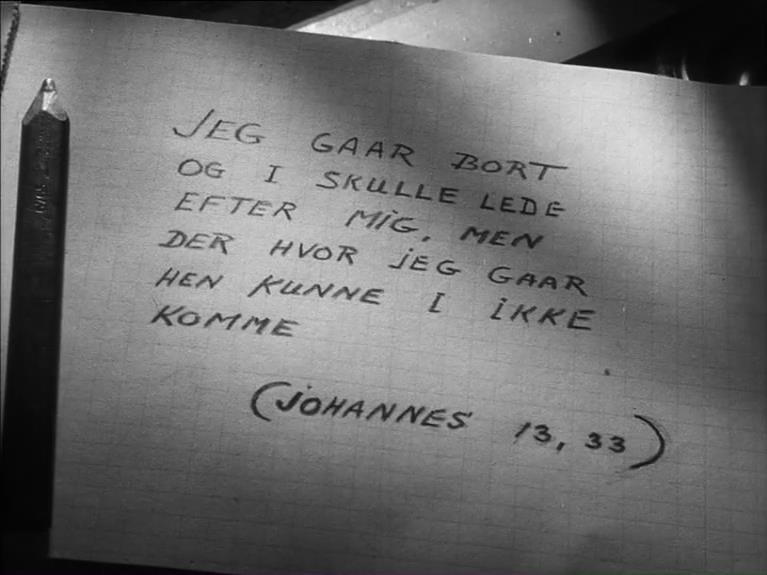

Before this climactic scene, however, a still-delusional Johannes has already attempted to raise his deceased sister-in-law back to life—and failed spectacularly. In the aftermath of this failure, Johannes absconds out the window of the Borgen homestead, explaining his sudden disappearance with a handwritten note. The note is a quotation taken from the book of John, which the English subtitles translate from the Danish as, “Yet a little while I am with you. Ye shall seek me. Whither I go, ye cannot come.”5 This is a quotation of Jesus, which comes as no surprise since up until this moment in the film Johannes consistently co-opts Christ’s words as his own. But Sitney seizes on an important detail, namely Johannes’s inclusion in the note of the scriptural location of the quotation, John 13:33 (Fig. 1).

Sitney writes, “In giving the location of the text Dreyer introduces a subtle note: here, for the first time, Johannes makes reference to the evangelical authority rather than quoting the words of Christ in his own voice. By quoting the fourth Gospel, he recovers his own name, Johannes.”6 This development in the story thus marks a change in Johannes’s self-understanding, shifting from erroneously believing himself to be Jesus to instead seeing himself as a witness to Jesus. “Johannes” is thus his true identity, both because this is his actual name and because he is following in the vocational footsteps of his biblical namesake i.e., Johannes/John.

But which John is Johannes patterned after? For Sitney, it’s John the Evangelist, author of the fourth gospel. His observation, outlined above, is compelling. That there is a shift in Johannes’s self-understanding pertaining to the name’s referent, thereby establishing a biblical antecedent for the character, is a profound insight. But, as illuminating as it is, I think Sitney is only half-right. Yes, understanding Johannes in the light of his Johannine antecedent is important, but I believe that his character makes more sense when understood as modelled not on John the Evangelist, but rather on John the Baptist. In order to arrive at this conclusion, however, we must pay close attention to an aspect of the film that has often been overlooked: lighting.

The Interpretive Significance of Light

Much of the critical discussion of Ordet has focused on its camerawork. Sitney, for example, discusses the camera with respect to what Dreyer called “rhythm-bound restlessness.”7 Similarly, film scholar David Bordwell details the way the camera’s movement exists in a kind of cinematographic limbo between complete preoccupation with narrative action (as per classical narration) and total narrative disinterest. It is only at the finale when the resurrection occurs that the film reverts to classical form, thereby signaling the miraculous via visual means.8 Even a single camera manoeuvre has attracted much interest thanks to its technical originality—and, indeed, the difficulty in explaining its execution.9 As scholar and critic Timothy Brayton puts it, “If Dreyer’s . . . The Passion of Joan of Arc is his film ‘about’ close- ups, Ordet is ‘about’ camera movement.”10 Dreyer was intentional about the film’s distinctive camera movement: “I believe that long takes represent the film of the future . . . Short scenes, quick cuts in my view mark the silent film, but the smooth medium shot—with continual camera movement—belongs to the sound film.”11 So important and innovative is Dreyer’s cinematography that Ordet has been cited as presaging the emergence of so-called slow cinema.12 Scholars are right, therefore, to attend to the film’s distinctive camerawork.

As noteworthy as the camerawork is, however, we ought not overlook the significance of the lighting. While arguably less conspicuous than Dreyer’s mobile framing, great care was taken over the use of light. Ordet’s cinematographer, Henning Bendtsen, recalls the exactitude of Dreyer’s lighting scheme:

Dreyer’s basic rule was to arrange people for the sake of photography and lighting rather than acting. Normally you work with a much simpler lighting plot in which the actors are not tied to a specific area because they must have the opportunity to act freely. In Ordet, their positions were so carefully planned that they had to count their steps at the same time as they said their lines. A single step too much to one side or the other would mean that we would miss a certain predetermined light effect and the scene would have to be reshot.13

This rigor was largely in service of realism. Though the influence of German expressionism is apparent in Dreyer’s earlier work, such as The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928), Vampyr (1932), and Day of Wrath (1943), the lighting in Ordet is more naturalistic. Dreyer once told film historian Jan Wahl, who as a young man serendipitously landed a job working on set during the filming of Ordet:

Because The Word [Ordet] is a realistic film, shadows, tones, lighting all must give characters a rounded and plastic appearance. It could not be done in the style, for example, of Murnau’s beautiful Faust, where the lighting had to originate from a single source in order to be allegorical, romantic.14

Indeed, this is precisely what we find in Ordet. Despite its realist aesthetic, however, the lighting has been painstakingly stylized to very particular ends. This is a result, I suggest, not only of Dreyer’s aesthetic proclivities, but also of the fact that light is one of the film’s major themes, though one that has been largely missed due to the relative paucity of attention paid to the lighting design. By analysing the lighting, we gain insight into the film’s light symbolism, which in turn sheds new light on the biblical identity of Johannes.

Light is also a verbal theme, cropping up intermittently in dialogue. Early on, Johannes declares, “I am the light of the world, but the darkness does not comprehend it.” He carries candles as he makes this delusional pronouncement so that, according to his reasoning, “my light may shine in the darkness.”15 These words are a paraphrased amalgam of John 1:5 and 8:12/9:5. Light figures also in a cluster of related metaphors: the patriarch, Morten (Henrik Malberg), laments that Johannes never became the prophet that he had hoped would be “the spark that would fire Christendom again”; Inger describes faith as “warm” and as a “glow inside”; and, in his eulogy, the minister (Ove Rud) speaks of the “bright hope” of life after death.

One of the most sophisticated instances of light symbolism comes as the doctor’s (Henry Skjær) car leaves, its headlights shining through the living room window and throwing a light onto the interior wall, which Johannes interprets as a vision of Death come for Inger. Though Johannes is ostensibly mistaken, the fact that Inger indeed dies at that moment creates ambiguity about the validity of his prophecies. Sitney makes another scintillating observation. This episode is a self-reflexive microcosm of how the film itself confronts us: this film too is nothing but light projected on a wall, one that, by its ending, may demand a metaphysical explanation but that we will be tempted to explain away rationally, thereby confirming in ourselves the faithlessness against which Johannes has been preaching all along.16 We are, therefore, complicit in the unbelief of the films’ skeptical characters. For this and the reasons listed above, light is an important aesthetic and thematic motif.

Shining Light on Johannine Identity

The secret to uncovering Johannine identity in Ordet is in the lighting of faces. Bendtsen has pointed out that the insane Johannes’s face is lit relatively dimly.17 On screen, the effect is subtle. Johannes moves in and out of shadow, so the lighting on his face is not uniformly dark.

Nevertheless, most of the time, Johannes’s face is lit only dimly. Of the eleven distinct scenes in which Johannes features, he is in predominantly dim light in all but the first and last (the former is explicable as a result of being set and filmed outside in the full light of day). The effect is especially pronounced when contrasted with the comparatively brightly lit faces of other characters. Johannes is often confined to the shadows, while other characters’ faces are fully, even ethereally lit (Fig. 2). When, however, Johannes returns to the homestead after a long disappearance, his face is fully illuminated (Fig. 3).

Extraordinary care was taken to achieve the effect. In addition to the example noted above, Bendtsen offers the following example:

Each image is composed like a painting in which the background and the lighting are carefully prepared. As an example, I might mention the prayer- meeting at Peter the tailor’s with twenty people sitting around. Normally we would have used one lamp for throwing light on all of them. Here we used twenty lamps so that each face in fact became an individual portrait study.18

Most pertinent to this discussion, however, is Bendtsen’s recollection of the pains he and Dreyer went to in order to light Johannes’s face distinctively:

Another of the lighting effects of the film created almost insoluble problems. While Johannes is insane, he is walking around in darkness all the time, whereas all the other characters have light on their faces. It created great difficulties when the characters moved around among each other, and the electricians had constantly to turn lamps on and off without this being noticed on the screen.19

Evidently, this laborious approach to lighting faces was important to what Dreyer hoped to achieve (for his part, Bendtsen won a Bodil Award, Denmark’s highest film accolade).20 But what does it mean? In his study of the holy fool archetype in cinema, Doebler writes that Ordet’s lighting design serves two purposes. Firstly, it marks Johannes’s return to sanity. Secondly, it “indicates Johannes’ unique light penetrating the spiritual darkness of the other characters.”21 While Doebler is right to assign spiritual meaning to the lighting, his point is unclear, since the reverse would appear to be true: the other characters’ light must have penetrated his, their light illuminating his shadowy face. After all, it is Johannes whose face is kept in relative darkness for most of the film. But interpreting the lighting design as implying that spiritual illumination flows from the other characters to Johannes would make no sense of the rest of the film, since, despite his delusions, Johannes is ultimately the catalyst of the miracle that brings spiritual enlightenment to the other characters.

On the other hand, quite a different interpretation could be advanced. Doebler’s point is interesting insofar as it raises the possibility that Johannes’s insanity affords him a kind of spiritual insight that the harsh light of rationalism obscures. This interpretation would be consistent with the holy fool archetype with which Doebler identifies Johannes. Indeed, in the eyes of other characters, Johannes remains a holy fool when, despite the restoration of his mental faculties, he still insists on the possibility of a miracle. As he summons Inger to arise from her coffin, the minister says, “He’s crazy” as he rises to his feet, only to be restrained, tellingly, by the doctor. It would even be possible to understand light as having a negative connotation, associated with the Enlightenment that undermined belief in the possibility of miracles. In this view, Johannes’s shadowy face would be evidence of spiritual perception, at odds with the blind rationalism of the others expressed in their “enlightened” visages. The biblical prophets were sometimes thought to be insane (e.g., Hos 9:7, Jer 29:26), and John the Baptist was considered by some to be possessed (e.g., Luke 7:33). Ultimately, however, this interpretation does not hold up. Prior to his mental restoration, still only dimly lit, Johannes’s attempt at resurrecting Inger fails. It is only having regained his sanity—stated explicitly by Morten—that Johannes’s resurrection attempt succeeds. While the Johannes of the climax may still appear “crazy” to the minister, he is intended to be understood as being in his right mind. The resulting miracle is proof. The indictment found in Hos 9:7 could well be applied to the minister: “Because your sins are so many and your hostility so great, the prophet is considered a fool, the inspired person a maniac.”

Perhaps there is an alternative explanation to that proffered by Doebler. There is a snippet of dialogue earlier in the film that might offer us a clue. Johannes pronounces a blessing over Maren (Ann Elisabeth Groth) and Little Inger (Susanne Rud): “The Lord be with you. The Lord bless you and keep you. The Lord let the light of His countenance shine upon you and give you grace. The Lord let the light of His countenance shine upon you and give you peace.” This is a loose quotation of Num 6:24–26, one in which Dreyer has made explicit the notion of light that is only implied by the language of “shine” used in the Bible.22 According to this slightly amended Mosaic benediction, spiritual light issues forth from God’s face, but that divine light may shine upon humans. This is borne out in the lighting of Johannes. Pictorially speaking, very little light shines upon Johannes until the climax.

What does this have to do with Johannine identity? Once Johannes has regained his sanity, marked visually by appearing in bright light, he then prays for “the Word that can make the dead come to life.” This takes us back, once again, to the book of John, which famously opens with the designation of Jesus Christ as “the Word” (John 1:1). The title, Ordet, Danish for “the Word”, suggests this is thematically crucial.23 Indeed, the entire book of John serves as an important touchstone for Ordet, a fact seemingly underscored by Johannes’s own name. Furthermore, John 1 draws a connection between light and Christ: “In [Jesus] was life, and that life was the light of all mankind. The light shines in the darkness, but the darkness has not overcome it” (John 1:4–5). But as we read on, John the Evangelist introduces us to another John: “There was a man sent from God whose name was John. He came as a witness to testify concerning that light, so that through him all might believe. He himself was not the light; he came only as a witness to the light” (John 1:6–8, my emphasis). These verses, which refer to John the Baptist, are an interpretive key (one we would not arrive at if we had not attended to the motif of light). Up until this point in the film, Johannes has erroneously believed that he is the light, a problem since, to quote Sitney,

so long as he believes he is the Savior, rather than an agent of the Word, and so far as he acts alone, rather than bolstered by the faith of a child, he is powerless. . . his transformation has been around a subtle theological axis, […] he has recognized his role as a vehicle for the Word, rather than as the Word Incarnate.24

Now he understands that, like John the Baptist, he is to be a witness to the light. In Sitney, therefore, we have a case of mistaken identity. Johannes’s biblical archetype is not John the Evangelist, author of the fourth gospel, but rather John the Baptist. John the Baptist’s function as a witness to the light unlocks the meaning of the lighting. In the finale, Johannes has for the first time understood that, like the Baptist, “He himself was not the light; he came only as a witness to the light” (John 1:8)—and this realization is reflected in the lighting change. In his delusional state, Johannes’s face was dim and shadowy, but now that he has been restored to his true vocation, his face is fully illuminated, reflecting the light of God and, more specifically, of Christ. For instance, when the still-delusional Johannes initially tries to resurrect Inger but fails, the lighting on his face is weak, especially in comparison to Mikkel (Emil Hass Christensen) and Inger (Fig. 2, bottom right). But his second attempt, performed once back to full mental and spiritual health, is successful, and so his face is strongly lit (Fig. 3). The first time we find Johannes prophesying, he says “God has summoned me to prophesy before his face.” Now that summons has finally been fulfilled and the proof is in his radiant visage. If we overlook light as a stylistic device and theme we miss the allusion to John 1:6–8 and therefore also miss John the Baptist as the interpretive key to unlocking the identity of Johannes.

Indeed, we find evidence that such an interpretation was intended by Dreyer when we consider a scene that did not make the final cut. Ordet, as we know it, elides the process of Johannes’s return to sanity; he is shown fleeing the homestead and then seen again only upon his return during Inger’s wake, fully restored. What precipitated Johannes’s cure? That is left a mystery, but this was apparently not always Dreyer’s intention. He did in fact film a scene in which this transformation is depicted. In it, Johannes prays for “The Word” that will bring Inger back to life and requests a sign. Wahl, who witnessed the shooting of this scene, recalls, “After this prayer, he closes his eyes. Then there is a blinding light—made by manoeuvring the gold and silver screens to reflect on his face. The sun emerges from the clouds; he accepts this as proof and says, ‘The sign. The sign!’”25 Though it never made the final cut, this moment suggests that interpreting the light on Johannes’s face as symbolic of reflected divine light is correct.

Dreyer himself apparently confirmed the identification of Johannes with the Baptist.

Speaking to Wahl, Dreyer said:

You will recall that John, when he was not preaching, was sometimes mistaken for Jesus. In Danish, John is called Johannes. [Kaj] Munk’s story in The Word tells of a divinity student who, in that period of intense study just before examinations, has suffered a mental collapse. He thereupon assumes the identity of Jesus.26

Dreyer is apparently referring here to the misconception, widely reported in the gospels, that Jesus was John the Baptist (e.g., Matt 16:13–14, Mark 8:27–28, Luke 9:18–19).27 Though the Baptist took pains to show that he was not the awaited messiah (e.g., Luke 3:15–17), he and Jesus are nevertheless closely associated in the gospels. Their close identification serves as Dreyer’s justification for his depiction of Johannes as an ersatz John the Baptist figure who mistakenly believes himself to be Jesus.

We find further evidence in favour of the interpretation of Johannes as an analogue of the Baptist by looking beyond Ordet to the screenplay for Dreyer’s planned Jesus of Nazareth,28 his would-be magnum opus that went tragically unrealized.29 For many years, Dreyer made plans for a film on the life of Jesus that would have marked, in his own estimation, the highpoint of his career.30 Indeed, Dreyer viewed Ordet as something of a practice run for his Jesus film, a chance to trial strategies for plausibly depicting a miracle, of which his film about Jesus would have had many.31 Alluding to the unseasonably wet weather during Ordet’s filming, Dreyer even quipped that “God is a little angry with me because I am not yet doing the Jesus-film.”32 Though Dreyer’s passion project never came to fruition, his script for the film offers some insight into what might have been. The very first words are those of a voice- over narrator: “There was a man sent from GOD, whose name was John. He was not the Light, but was sent to bear witness of [sic] the light, the true Light”—a near-verbatim quotation of John 1:8–9.33 The opening scene that follows on its heels depicts the Baptist preaching and recognising Jesus as the Messiah, while also insisting that he himself is not the promised Messiah. A few pages later, Jesus says:

He has borne witness of me and I know that witness is true. He is the burning and shining light. For I say unto you: among those that are born of women there is no greater Prophet than John the Baptist . . . but he that is least in the Kingdom of God is greater than he.

Though the Baptist makes no further appearances in the script and is mentioned on only a couple of other occasions,34 that John the Baptist’s witness to the light of Christ serves as the film’s opening suggests that this particular vocation of the Baptist loomed large in Dreyer’s thinking (though, somewhat puzzlingly, he also identifies the Baptist with light in the quotation above). As important as the book of John is to understanding Ordet, Johannes is apparently modelled after the Baptist, particularly as described in John 1, rather than the Evangelist.

New Meaning: A Celebration of the Prophetic

But what difference does it make? Sitney’s identification of Johannes with John the Evangelist might seem to amount to much the same thing. After all, the Evangelist is also a witness to the light of Christ, even if not explicitly described as such in John 1. But the association with John the Baptist clarifies and alters its meaning. Below, I sketch three insights afforded by this interpretation, all of which are related either directly or indirectly to the prophetic.

Firstly, this interpretation casts the sane Johannes in a more strictly prophetic role. Jesus described John the Baptist as a prophet and the greatest “among those born of women” (Matt11:11). Jesus even called him “the Elijah who was to come” (Matt 11:14), invoking a tradition beginning in Old Testament (Mal 4:5–6) and expanded in deuterocanonical literature (Sir 48:10) that held that the prophet Elijah would one day return to facilitate reconciliation and restore Israel before the Day of the LORD.35 According to Jesus, John the Baptist is the Hebrew prophet par excellence. This interpretation gives positive, not solely negative, meaning to Johannes’s character arc; the restoration of Johannes’s sanity entails not merely the absence of delusion, but also the recovery of his prophetic vocation.

Secondly, and relatedly, it shows that the prayers of Morten have finally been answered. Early in the film, we learn that Morten has grown cynical about prayer’s efficacy due to unanswered prayers, not only petitions for Johannes’s restoration but also his prayers that Johannes, once a popular preacher, would become “the prophet that should come . . . the renewer.” Once Johannes embraces his true vocation as a witness to the light, rather than labouring under the delusion that he himself is the light, he finally steps into his prophetic role. Prayers that Morten believed to have gone unheeded turn out, therefore, to be answered affirmatively in the end. Of course, without John the Baptist as an interpretive lens, this prophetic dimension to the sane Johannes would be obscured and we would thus be deprived of the realisation that God has answered Morten’s prayers for Johannes’s prophetic ministry (though we would realize that God had at least answered his prayers for Johannes’s mental restoration). This adds weight to Dreyer’s stated aim: “This is a theme . . . that suits me— Faith’s triumph in the skeptical twentieth century over Science and Rationalism.”36

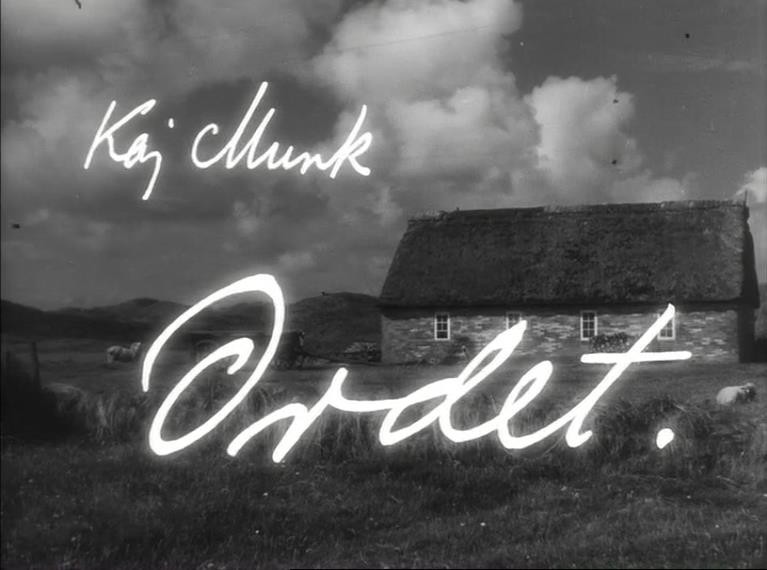

Thirdly, it opens up the possibility of Johannes being a kind of stand-in for Kaj Munk, playwright of the eponymous stage play of which Ordet is an adaptation. Munk, a Lutheran pastor, was well-aware of the significance of John the Baptist. Dreyer recalled that “Kaj Munk described John the Baptist as being a man who was not extremely cautious, a man who spoke out the truth no matter the cost.”37 Perhaps this is the reason for naming the character Johannes.

If, however, Munk’s intention was to identify Johannes with the Baptist, there is little else in his script for The Word that would suggest such an interpretation. Neither the Baptist nor light (that would obliquely allude to him) figure as themes in Munk’s original work. Thus, the alignment of Johannes with the Baptist is Dreyer’s innovation, or at the very least, his making plain what was otherwise, at most, only implicit and ambiguous in Munk’s version. (About adaptation, Dreyer once said, “You must revitalize a work when you give it a different form. You cannot merely try to copy. You must try to give it full value, shedding new light.”38 He seems here to have taken the final part of this principle quite literally.)

What was Dreyer’s intention in adding or accentuating John the Baptist as an interpretive key? It may be a tribute to Munk himself. According to Dreyer, “Munk shouted accusations against the Germans, just as the Baptist had told the truth about King Herod.”39 Clearly, there was an association in Dreyer’s mind between Munk and the Baptist. Like the Baptist, Munk was an outspoken critic of the occupying regime, namely the Nazis during World War II. And, like the Baptist, Munk was executed for his dissent, shot thrice in the head and left in a ditch by Nazi officers under direct orders from Berlin in 1944.40 The parallels between these two prophetic figures were not lost on Dreyer.

Sharp critique of the Nazis mattered a great deal to Dreyer. His Jesus film was informed by a desire to condemn the anti-Semitic scourge of recent European history.41 In the screenplay, Jesus’ traditional nemeses, the Pharisees, are presented in a sympathetic light, eager to give Jesus a fair hearing. Even Judas’s betrayal is portrayed as less traitorous than simply tragically misguided, an act of wrongheaded loyalty. Blame for Jesus’s death is thus laid at the feet of the occupying forces, the Romans. Indeed, an early draft was titled The Story of the Jew Jesus, and Dreyer planned to cast Jewish actors in the lead roles, a corrective to his casting a fair- skinned Jesus in his Leaves from Satan’s Book (1921), a creative compromise he later regretted.42 As such, Variety’s Todd McCarthy championed Dreyer’s screenplay as the cinematic antidote to the perceived anti-Semitism of The Passion of the Christ (Mel Gibson, 2004).43 That opposition to the Nazis cost Munk his life must have struck Dreyer as heroic. Giving Johannes a Baptist-like function in Ordet is possibly intended as a subtle tribute to the playwright. Indeed, Ordet has no opening or closing credits except to grant Munk a possessory credit (Fig. 4). It seems likely that the film is meant to indirectly pay tribute to its original author, a modern-day John the Baptist.

Conclusions

Ordet enjoys a stellar reputation, especially among enthusiasts of so-called religious cinema. That this celebrated film frequently alludes to the book of John is well known, perhaps even obvious to viewers well-acquainted with the Bible. Drawing an equivalence between Johannes and John the Evangelist, as per Sitney, therefore, initially appears sound. But the development of lighting over the course of the film, especially with respect to the way faces are lit, coupled with other light symbolism deployed throughout suggests it is more fruitful to see Johannes’s antecedent as John the Baptist. Seen in this light, Johannes emerges as a prophetic figure (which, in turn, signals an answer to his father’s prayers for a prophetic awakening), and possibly even a veiled reference to the playwright of the original Ordet, Kaj Munk, whose John the Baptist-like critique of the occupying regime during World War II Denmark led to his murder at the hands of the Nazis.

This adds a new dimension to our understanding of this important film, one in which the prophetic is accentuated. Given its prominence in the canon of religious cinema, any interpretation that expands or improves our understanding of Ordet holds some significance for the field of religion and film. But this study also has implications for the discipline beyond Ordet specifically. As mentioned in the introduction, scholars have identified the need for religion and film to break free from its “literary captivity” by focusing on the audiovisual dimensions of film, rather than more “literary” elements like plot, character, and theme.44 Moreover, when formal analyses are undertaken, the result is sometimes a “Nestorian” separation of form and theme, as if the two were not interdependent.45 There are plenty of reasons to pay attention to film form that go beyond mere thematic value, but this study serves as a modest example of how close examination of image may yield a richer “reading” of a film’s themes. In other words, even our understanding of theme alone suffers when form is downplayed or ignored. By attending to the images of Ordet with respect to lighting, we are enabled to see this seminal old film, quite literally, in a new light.

- 1 Torben Skjøt Jensen, "Carl Th. Dreyer—My Metier," (1995). ↵

- For an exception, see Peter L Doebler, "Jest in Time: The Problems and Promises of the Holy Fool in Francesco, Giullare Di Dio, Ordet, and Ikiru," Journal of Religion & Film 17:1 (April 2013). ↵

- Ordet is ranked 24th-equal in "The 50 Greatest Films of All Time," BFI, 2012, greatest-films-all-time (August 30 2018). ↵