Readings

Creativity – New World Encyclopedia

Chapter 1 – Definitions of Creativity

Chapter 2 – Creativity in psychology & cognitive science

Chapter 3 – Creativity in Various Contexts

Chapter 4 – References

1. Definitions of Creativity

https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/p/index.php?title=Creativity&oldid=1036787

Creativity is a process involving the generation of new ideas or concepts, or new associations between existing ideas or concepts, and their substantiation into a product that has novelty and originality. From a scientific point of view, the products of creative thought (sometimes referred to as divergent thought) are usually considered to have both “originality” and “appropriateness.” An alternative, more everyday conception of creativity is that it is simply the act of making something new.

Although intuitively a simple phenomenon, creativity is in fact quite complex. It has been studied from numerous perspectives, including psychology, social psychology, psychometrics, artificial intelligence, philosophy, history, economics, and business. Unlike many phenomena in science, there is no single, authoritative perspective, or definition of creativity; nor is there a standardized measurement technique. Creativity has been attributed variously to divine intervention or spiritual inspiration, cognitive processes, the social environment, personality traits, and chance (“accident” or “serendipity”). It has been associated with genius, mental illness and humor. Some say it is a trait we are born with; others say it can be taught with the application of simple techniques. Although popularly associated with art and literature, it is also an essential part of innovation and invention, important in professions such as business, economics, architecture, industrial design, science, and engineering. Despite, or perhaps because of, the ambiguity and multi-dimensional nature of creativity, entire industries have been spawned from the pursuit of creative ideas and the development of creativity techniques.

This mysterious phenomenon, though undeniably important and constantly visible, seems to lie tantalizingly beyond the grasp of scientific investigation. Yet in religious or spiritual terms it is the very essence of human nature. Creativity, understood as the ability to utilize everything at hand in nature to transform our living environment and beautify our lives, is what distinguishes human beings from all other creatures. This is one way that human beings are said to be in the image of God: they are second creators, acting in a manner analogous to God, the original Creator.

Moreover, all people, regardless of their intellectual level, are co-creators of perhaps the most important thing—their own self. While God provides each person with a certain endowment and circumstance, it is up to each individual to make what he will of his life by how he or she choses to live it.

Definitions of Creativity

“Creativity, it has been said, consists largely of re-arranging what we know in order to find out what we do not know.” George Keller

“The problem of creativity is beset with mysticism, confused definitions, value judgments, psychoanalytic admonitions, and the crushing weight of philosophical speculation dating from ancient times.” Albert Rothenberg

More than 60 different definitions of creativity can be found in the psychological literature.[1] The etymological root of the word in English and most other European languages comes from the Latin creatus, literally “to have grown.”

Perhaps the most widespread conception of creativity in the scholarly literature is that creativity is manifested in the production of a creative work (for example, a new work of art or a scientific hypothesis) that is both “novel” and “useful.” Colloquial definitions of creativity are typically descriptive of activity that results in producing or bringing about something partly or wholly new; in investing an existing object with new properties or characteristics; in imagining new possibilities that were not conceived of before; and in seeing or performing something in a manner different from what was thought possible or normal previously.

A useful distinction has been made by Rhodes[2] between the creative person, the creative product, the creative process, and the creative “press” or environment. Each of these factors are usually present in creative activity. This has been elaborated by Johnson,[3] who suggested that creative activity may exhibit several dimensions including sensitivity to problems on the part of the creative agent, originality, ingenuity, unusualness, usefulness, and appropriateness in relation to the creative product, and intellectual leadership on the part of the creative agent.

Boden[4] noted that it is important to distinguish between ideas which are psychologically creative (which are novel to the individual mind which had the idea), and those which are historically creative (which are novel with respect to the whole of human history). Drawing on ideas from artificial intelligence, she defines psychologically creative ideas as those which cannot be produced by the same set of generative rules as other, familiar ideas.

Often implied in the notion of creativity is a concomitant presence of inspiration, cognitive leaps, or intuitive insight as a part of creative thought and action.[5] Pop psychology sometimes associates creativity with right or forehead brain activity or even specifically with lateral thinking.

Some students of creativity have emphasized an element of chance in the creative process. Linus Pauling, asked at a public lecture how one creates scientific theories, replied that one must endeavor to come up with many ideas, then discard the useless ones.

History of the term and the concept

The way in which different societies have formulated the concept of creativity has changed throughout history, as has the term “creativity” itself.

The ancient Greeks, who believed that the muses were the source of all inspiration, actually had no terms corresponding to “to create” or “creator.” The expression “poiein” (“to make”) sufficed. They believed that the inspiration for originality came from the gods and even invented heavenly creatures – the Muses – as supervisors of human creativity.

According to Plato, Socrates taught that inspired thoughts originate with the gods; ideas spring forth not when a person is rational, but when someone is “beside himself,” when “bereft of his senses.” Since the gods took away reason before bestowing the gift of inspiration, “thinking” might actually prevent the reception of divinely inspired revelations. The word “inspiration” is based on a Greek word meaning “the God within.” The poet was seen as making new things—bringing to life a new world—while the artist merely imitated.

In the visual arts, freedom was limited by the proportions that Polyclitus had established for the human frame, and which he called “the canon” (meaning, “measure”). Plato argued in Timaeus that, to execute a good work, one must contemplate an eternal model. Later the Roman, Cicero, would write that art embraces those things “of which we have knowledge” (quae sciuntur).

In Rome, these Greek concepts were partly shaken. Horace wrote that not only poets but painters as well were entitled to the privilege of daring whatever they wished to (quod libet audendi). In the declining period of antiquity, Philostratus wrote that “one can discover a similarity between poetry and art and find that they have imagination in common.” Callistratos averred that “Not only is the art of the poets and prosaists inspired, but likewise the hands of sculptors are gifted with the blessing of divine inspiration.” This was something new: classical Greeks had not applied the concepts of imagination and inspiration to the visual arts but had restricted them to poetry. Latin was richer than Greek: it had a term for “creating” (creatio) and for creator, and had two expressions—facere and creare—where Greek had but one, poiein.[6] Still, the two Latin terms meant much the same thing.

Although neither the Greeks nor the Romans had any words that directly corresponded to the word creativity, their art, architecture, music, inventions, and discoveries provide numerous examples of what we would today describe as creative works. At the time, the concept of genius probably came closest to describing the creative talents bringing forth these works.[7]

A fundamental change came in the Christian period: creatio came to designate God’s act of “creation from nothing.” Creatio thus took on a different meaning than facere (“to make”), and ceased to apply to human functions.

The influential Christian writer Saint Augustine felt that Christianity “played a leading role in the discovery of our power to create” (Albert & Runco, 1999). However, alongside this new, religious interpretation of the expression, there persisted the ancient view that art is not a domain of creativity.[6] This is also seen in the work of Pseudo-Dionysius. Later medieval men such as Hraban the Moor, and Robert Grosseteste in the thirteenth century, thought much the same way. The Middle Ages here went even further than antiquity; they made no exception of poetry: it too had its rules, was an art, and was therefore craft, and not creativity.

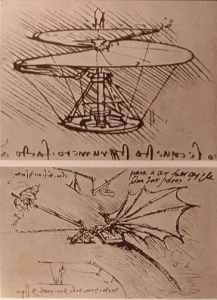

Another shift occurred in more modern times. Renaissance men had a sense of their own independence, freedom and creativity, and sought to give voice to this sense of independence and creativity. Baltasar Gracián (1601-1658) wrote: “Art is the completion of nature, as it were ‘a second Creator'”; … Raphael, that he shapes a painting according to his idea; Leonardo da Vinci, that he employs “shapes that do not exist in nature”; Michelangelo, that the artist realizes his vision rather than imitating nature. Still more emphatic were those who wrote about poetry: G.P. Capriano held (1555) that the poet’s invention springs “from nothing.” Francesco Patrizi (1586) saw poetry as “fiction,” “shaping,” and “transformation.”

Finally, at long last, someone ventured to use the word, “creation.” He was the seventh-century Polish poet and theoretician of poetry, Maciej Kazimierz Sarbiewski (1595-1640), known as “the last Latin poet.” In his treatise, De perfecta poesi, he not only wrote that a poet “invents,” “after a fashion builds,” but also that the poet “creates anew” (de novo creat). Sarbiewski even added: “in the manner of God” (instar Dei).

By the eighteenth century and the Age of Enlightenment, the concept of creativity was appearing more often in art theory, and was linked with the concept of imagination.[6] There was still resistance to the idea of human creativity which had a triple source. The expression, “creation,” was then reserved for creation ex nihilo (Latin: “from nothing”), which was inaccessible to man. Second, creation is a mysterious act, and Enlightenment psychology did not admit of mysteries. Third, artists of the age were attached to their rules, and creativity seemed irreconcilable with rules. The latter objection was the weakest, as it was already beginning to be realized (e.g., by Houdar de la Motte, 1715) that rules ultimately are a human invention.

The Western view of creativity can be contrasted with the Eastern view. For the Hindus, Confucius, Daoists and Buddhists, creation was at most a kind of discovery or mimicry, and the idea of creation from “nothing” had no place in these philosophies and religions.[7]

In the nineteenth century, not only was art regarded as creativity, but “it alone” was so regarded. When later, at the turn of the twentieth century, there began to be discussion of creativity in the sciences (e.g., Jan Łukasiewicz, 1878-1956) and in nature (such as Henri Bergson), this was generally taken as the transference to the sciences of concepts proper to art.[6]

The formal starting point of the scientific study of creativity is sometimes considered to be J. P. Guilford’s address to the American Psychological Association in 1950, which helped to popularize the topic[8]. Since then (and indeed, before then), researchers from a variety of fields have studied the nature of creativity from a scientific point of view. Others have taken a more pragmatic approach, teaching practical creativity techniques. Three of the best-known are Alex Osborn’s brainstorming techniques, Genrikh Altshuller’s Theory of Inventive Problem Solving (TRIZ); and Edward de Bono’s lateral thinking.

Notes

C.W. Taylor, “Various approaches to and definitions of creativity.” in The nature of creativity: Contemporary psychological perspectives, ed. R.J. Sternberg, (Cambridge University Press, 1988. ISBN 0521338921)

M. Rhodes, 1961 “An analysis of creativity.” Phi Delta Kappan 42: 305-311

D.M. Johnson. Systematic introduction to the psychology of thinking. (Harper & Row, 1972. ISBN 0060433310)

M.A. Boden. 2004 The Creative Mind: Myths And Mechanisms. (Routledge ISBN 0465014518)

A. Koestler. The Act of Creation. (Macmillan, 1975 ISBN 0330244477)

Władysław Tatarkiewicz. A History of Six Ideas: an Essay in Aesthetics, Translated from the Polish by Christopher Kasparek, (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1980. ISBN 9024722330)

R.S. Albert, & M.A. Runce, “A History of Research on Creativity” in Handbook of Creativity, ed. R.J. Sternberg, (Cambridge University Press, 1999. ISBN 0521576040)

R.J. Sternberg, and T.I. Lubart, “The Concept of Creativity: Prospects and Paradigms.” Handbook of Creativity, ed. R.J. Sternberg, (Cambridge University Press, 1999 ISBN 0521576040)

G. Wallas. Art of Thought. (Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1926 ASIN B000GRK1P6)

D.K. Simonton. 1999 Origins of genius: Darwinian perspectives on creativity. (Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195128796)

T. Ward, 2003 “Creativity.” L. title=Encyclopaedia of Cognition, ed. L. Nagel, (New York, Macmillan)

S.M. Smith, & S.E. Blakenship, 1991 “Incubation and the persistence of fixation in problem solving.” American Journal of Psychology 104: 61–87

J.R. Anderson. 2005 Cognitive psychology and its implications. (Worth Publishers. ISBN 0716701103)

J.P. Guilford. The Nature of Human Intelligence. (McGraw-Hill ASIN B000IFVRKE)

R. Finke, T.B. Ward, & S.M. Smith, 1996 Creative cognition: Theory, research, and applications. (MIT Press. ISBN 0262560968)

R.W. Weisberg. 1993 Creativity: Beyond the myth of genius. Freeman ISBN 0716723670)

L.A. O’Hara, & R.J. Sternberg, “Creativity and Intelligence.” in Handbook of Creativity, ed. R.J. Sternberg, (Cambridge University Press, 1999)

Fred Balzac, 2006 Exploring the Brain’s Role in Creativity NeuroPsychiatry Reviews 7 (5): 1, 19-20

J.P. Rushton, “Creativity, intelligence, and psychoticism.” Personality and Individual Differences 1990 11: 1291-1298

Melanie Moran. Odd behavior and creativity may go hand in hand September 6, 2005.

T.M. Amabile, 1998 “How to kill creativity.” Harvard Business Review 76 (5)

K. Dorst, and N. Cross, 2001 “Creativity in the design process: co-evolution of problem–solution.” Design Studies 22 (5) :425-437

National Academy of Engineering. 2005 Educating the engineer of 2020: adapting engineering education to the new century. (National Academies Press )

Creative Industries Mapping Document 2001. an overview of creative industries in the UK.

I. Nonaka, 1991. “The Knowledge-Creating Company.” Harvard Business Review 69 (6): 96-104

T. M. Amabile, R. Conti, H. Coon, et al. 1996 “Assessing the work environment for creativity.” Academy of Management Review 39 (5): 1154-1184

Amabile et al., 1996: 1154-1155, (emphasis added)

Patrick M. Jones, “Music Education and the Knowledge Economy: Developing Creativity, Strengthening Communities.” Arts Education Policy Review (Mar/Apr 2005) 106 (4): 5-12, 3 charts

U. Kraft, “Unleashing Creativity.” Scientific American Mind 2005 (April): 16-23

R.R. McCrae, “Creativity, Divergent Thinking, and Openness to Experience.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology (1987) 52 (6): 1258-1265

D.H. Pink. 2005 A Whole New Mind: Moving from the information age into the conceptual age. (Riverhead. ISBN 1573223085)

R.S. Nickerson, “Enhancing Creativity.” Handbook of Creativity.

Swedish Morphological Society. Retrieved June 13, 2008.

quoted in Ian S. Markham. A World Religions Reader. (Blackwell Publishing, 2000. ISBN 0631215190)

Gleanings from the Writings of Bahá’u’lláh [1] bahai.org. Retrieved September 30, 2008.

Dirk H. Kelder. 1998. Nikolai Berdyaev. Retrieved June 13, 2008.

Alfred North Whitehead. Process and Reality. (New York: Free Press, 1979 ISBN 0029345707)

M.A. Runco, 2004 “Creativity.” Annual Review of Psychology 55: 657-687

D.H. Feldman, “The Development of Creativity.” Handbook of Creativity.

R.B. McLaren, “Dark Side of Creativity.” Encyclopedia of Creativity, eds. M.A. Runco, & S.R. Pritzker, publisher=(Academic Press. 1999 ISBN 0122270754)

BCA 2006. New Concepts in Innovation: The Keys to a Growing Australia. Business Council of Australia. Retrieved June 13, 2008.

2. Creativity in psychology & cognitive science

An early, psychodynamic approach to understanding creativity was proposed by Sigmund Freud, who suggested that creativity arises as a result of frustrated desires for fame, fortune, and love, with the energy that was previously tied up in frustration and emotional tension in the neurosis being sublimated into creative activity. Freud later retracted this view.

Graham Wallas, in his work Art of Thought, published in 1926,[9] presented one of the first models of the creative process. Wallas considered creativity to be a legacy of the evolutionary process, which allowed humans to quickly adapt to rapidly changing environments.[10]

In the Wallas stage model, creative insights and illuminations may be explained by a process consisting of 5 stages:

preparation (preparatory work on a problem that focuses the individual’s mind on the problem and explores the problem’s dimensions),

incubation (where the problem is internalized into the subconscious mind and nothing appears externally to be happening),

intimation (the creative person gets a “feeling” that a solution is on its way),

illumination or insight (where the creative idea bursts forth from its subconscious processing into conscious awareness); and

verification (where the idea is consciously verified, elaborated, and then applied).

Wallas’ model has subsequently been treated as four stages, with “intimation” seen as a sub-stage. There has been some empirical research looking at whether, as the concept of “incubation” in Wallas’ model implies, a period of interruption or rest from a problem may aid creative problem-solving. Ward[11] lists various hypotheses that have been advanced to explain why incubation may aid creative problem-solving, and notes how some empirical evidence is consistent with the hypothesis that incubation aids creative problem-solving in that it enables “forgetting” of misleading clues. Absence of incubation may lead the problem solver to become fixated on inappropriate strategies of solving the problem.[12] This work disputed the earlier hypothesis that creative solutions to problems arise mysteriously from the unconscious mind while the conscious mind is occupied on other tasks.[13]

Guilford[14] performed important work in the field of creativity, drawing a distinction between convergent and divergent production (commonly renamed convergent and divergent thinking). Convergent thinking involves aiming for a single, correct solution to a problem, whereas divergent thinking involves creative generation of multiple answers to a set problem. Divergent thinking is sometimes used as a synonym for creativity in psychology literature. Other researchers have occasionally used the terms “flexible” thinking or “fluid intelligence,” which are similar to (but not synonymous with) creativity.

In The Act of Creation, Arthur Koestler[5] listed three types of creative individuals: the “Artist,” the “Sage,” and the “Jester.” Believers in this trinity hold all three elements necessary in business and can identify them all in “truly creative” companies as well. Koestler introduced the concept of “bisociation”—that creativity arises as a result of the intersection of two quite different frames of reference.

In 1992, Finke[15] proposed the “Geneplore” model, in which creativity takes place in two phases: a generative phase, where an individual constructs mental representations called preinventive structures, and an exploratory phase where those structures are used to come up with creative ideas. Weisberg[16] argued, by contrast, that creativity only involves ordinary cognitive processes yielding extraordinary results.

Creativity and intelligence

There has been debate in the psychological literature about whether intelligence and creativity are part of the same process (the conjoint hypothesis) or represent distinct mental processes (the disjoint hypothesis). Evidence from attempts to look at correlations between intelligence and creativity from the 1950s onwards regularly suggested that correlations between these concepts were low enough to justify treating them as distinct concepts.

It has been proposed that creativity is the outcome of the same cognitive processes as intelligence, and is only judged as creativity in terms of its consequences. In other words, the process is only judged creative when the outcome of cognitive processes happen to produce something novel, a view which Perkins has termed the “nothing special” hypothesis.[17] However, a very popular model is what has come to be known as “the threshold hypothesis,” stating that intelligence and creativity are more likely to be correlated in general samples, but that this correlation is not found in people with IQs over 120. An alternative perspective, Renculli’s three-rings hypothesis, sees giftedness as based on both intelligence and creativity.

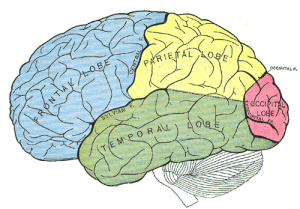

Neurology of creativity

Neurological research has found that creative innovation requires “coactivation and communication between regions of the brain that ordinarily are not strongly connected.”[18] Highly creative people who excel at creative innovation tend to differ from others in three ways: they have a high level of specialized knowledge, they are capable of divergent thinking mediated by the frontal lobe, and they are able to modulate neurotransmitters such as norepinephrine in their frontal lobe. Thus, the frontal lobe appears to be the part of the cortex that is most important for creativity.[18]

Creativity and madness

Creativity has been found to correlate with intelligence and psychoticism,[19] particularly in schizotypal individuals.[20] To explain these results, it has been hypothesized that such individuals are better at accessing both hemispheres, allowing them to make novel associations at a faster rate. In agreement with this hypothesis, ambidexterity is also associated with schizotypal and schizophrenic individuals.

Notes

C.W. Taylor, “Various approaches to and definitions of creativity.” in The nature of creativity: Contemporary psychological perspectives, ed. R.J. Sternberg, (Cambridge University Press, 1988. ISBN 0521338921)

M. Rhodes, 1961 “An analysis of creativity.” Phi Delta Kappan 42: 305-311

D.M. Johnson. Systematic introduction to the psychology of thinking. (Harper & Row, 1972. ISBN 0060433310)

M.A. Boden. 2004 The Creative Mind: Myths And Mechanisms. (Routledge ISBN 0465014518)

A. Koestler. The Act of Creation. (Macmillan, 1975 ISBN 0330244477)

Władysław Tatarkiewicz. A History of Six Ideas: an Essay in Aesthetics, Translated from the Polish by Christopher Kasparek, (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1980. ISBN 9024722330)

R.S. Albert, & M.A. Runce, “A History of Research on Creativity” in Handbook of Creativity, ed. R.J. Sternberg, (Cambridge University Press, 1999. ISBN 0521576040)

R.J. Sternberg, and T.I. Lubart, “The Concept of Creativity: Prospects and Paradigms.” Handbook of Creativity, ed. R.J. Sternberg, (Cambridge University Press, 1999 ISBN 0521576040)

G. Wallas. Art of Thought. (Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1926 ASIN B000GRK1P6)

D.K. Simonton. 1999 Origins of genius: Darwinian perspectives on creativity. (Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195128796)

T. Ward, 2003 “Creativity.” L. title=Encyclopaedia of Cognition, ed. L. Nagel, (New York, Macmillan)

S.M. Smith, & S.E. Blakenship, 1991 “Incubation and the persistence of fixation in problem solving.” American Journal of Psychology 104: 61–87

J.R. Anderson. 2005 Cognitive psychology and its implications. (Worth Publishers. ISBN 0716701103)

J.P. Guilford. The Nature of Human Intelligence. (McGraw-Hill ASIN B000IFVRKE)

R. Finke, T.B. Ward, & S.M. Smith, 1996 Creative cognition: Theory, research, and applications. (MIT Press. ISBN 0262560968)

R.W. Weisberg. 1993 Creativity: Beyond the myth of genius. Freeman ISBN 0716723670)

L.A. O’Hara, & R.J. Sternberg, “Creativity and Intelligence.” in Handbook of Creativity, ed. R.J. Sternberg, (Cambridge University Press, 1999)

Fred Balzac, 2006 Exploring the Brain’s Role in Creativity NeuroPsychiatry Reviews 7 (5): 1, 19-20

J.P. Rushton, “Creativity, intelligence, and psychoticism.” Personality and Individual Differences 1990 11: 1291-1298

Melanie Moran. Odd behavior and creativity may go hand in hand September 6, 2005.

T.M. Amabile, 1998 “How to kill creativity.” Harvard Business Review 76 (5)

K. Dorst, and N. Cross, 2001 “Creativity in the design process: co-evolution of problem–solution.” Design Studies 22 (5) :425-437

National Academy of Engineering. 2005 Educating the engineer of 2020: adapting engineering education to the new century. (National Academies Press )

Creative Industries Mapping Document 2001. an overview of creative industries in the UK.

I. Nonaka, 1991. “The Knowledge-Creating Company.” Harvard Business Review 69 (6): 96-104

T. M. Amabile, R. Conti, H. Coon, et al. 1996 “Assessing the work environment for creativity.” Academy of Management Review 39 (5): 1154-1184

Amabile et al., 1996: 1154-1155, (emphasis added)

Patrick M. Jones, “Music Education and the Knowledge Economy: Developing Creativity, Strengthening Communities.” Arts Education Policy Review (Mar/Apr 2005) 106 (4): 5-12, 3 charts

U. Kraft, “Unleashing Creativity.” Scientific American Mind 2005 (April): 16-23

R.R. McCrae, “Creativity, Divergent Thinking, and Openness to Experience.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology (1987) 52 (6): 1258-1265

D.H. Pink. 2005 A Whole New Mind: Moving from the information age into the conceptual age. (Riverhead. ISBN 1573223085)

R.S. Nickerson, “Enhancing Creativity.” Handbook of Creativity.

Swedish Morphological Society. Retrieved June 13, 2008.

quoted in Ian S. Markham. A World Religions Reader. (Blackwell Publishing, 2000. ISBN 0631215190)

Gleanings from the Writings of Bahá’u’lláh [1] bahai.org. Retrieved September 30, 2008.

Dirk H. Kelder. 1998. Nikolai Berdyaev. Retrieved June 13, 2008.

Alfred North Whitehead. Process and Reality. (New York: Free Press, 1979 ISBN 0029345707)

M.A. Runco, 2004 “Creativity.” Annual Review of Psychology 55: 657-687

D.H. Feldman, “The Development of Creativity.” Handbook of Creativity.

R.B. McLaren, “Dark Side of Creativity.” Encyclopedia of Creativity, eds. M.A. Runco, & S.R. Pritzker, publisher=(Academic Press. 1999 ISBN 0122270754)

BCA 2006. New Concepts in Innovation: The Keys to a Growing Australia. Business Council of Australia. Retrieved June 13, 2008.

3. Creativity in Various Contexts

Creativity has been studied from a variety of perspectives and is important in numerous contexts. Most of these approaches are unidisciplinary, and it is therefore difficult to form a coherent overall view.[8] The following sections examine some of the areas in which creativity is seen as being important.

Creativity in art & literature

Most people associate creativity with the fields of art and literature. In these fields, “originality” is considered to be a sufficient condition for creativity, unlike other fields where both “originality” and “appropriateness” are necessary.[21]

Within the different modes of artistic expression, one can postulate a continuum extending from “interpretation” to “innovation.” Established artistic movements and genres pull practitioners to the “interpretation” end of the scale, whereas original thinkers strive towards the “innovation” pole. Note that we conventionally expect some “creative” people (dancers, actors, orchestral members, etc.) to perform (interpret) while allowing others (writers, painters, composers, etc.) more freedom to express the new and the different.

The word “creativity” conveys an implication of constructing novelty without relying on any existing constituent components (ex nihilo – compare creationism). Contrast alternative theories, for example:

artistic inspiration, which provides the transmission of visions from divine sources such as the Muses; a taste of the Divine.

artistic evolution, which stresses obeying established (“classical”) rules and imitating or appropriating to produce subtly different but unshockingly understandable work.

In the art, practice, and theory of Davor Dzalto, human creativity is taken as a basic feature of both the personal existence of human beings and art production.

Creativity in science, engineering and design

Creativity is also seen as being increasingly important in a variety of other professions. Architecture and industrial design are the fields most often associated with creativity, and more generally the fields of design and design research. These fields explicitly value creativity, and journals such as Design Studies have published many studies on creativity and creative problem solving.[22]

Fields such as science and engineering have, by contrast, experienced a less explicit (but arguably no less important) relation to creativity. Simonton[10] shows how some of the major scientific advances of the twentieth century can be attributed to the creativity of individuals. This ability will also be seen as increasingly important for engineers in years to come.[23]

Creativity in business

Creativity, broadly conceived, is essential to all successful business ventures. Entrepreneurs use creativity to define a market, promote a product or service, and make unconventional deals with providers, partners and lenders. Narrowly speaking, there is a growing sector of “creative industries” — capitalistically generating (generally non-tangible) wealth through the creation and exploitation of intellectual property or through the provision of creative services.[24]

Amabile[21] argues that to enhance creativity in business, three components were needed: Expertise (technical, procedural, and intellectual knowledge), Creative thinking skills (how flexibly and imaginatively people approach problems), and Motivation (especially intrinsic motivation). Nonaka, who examined several successful Japanese companies, similarly saw creativity and knowledge creation as being important to the success of organizations.[25] In particular, he emphasized the role that tacit knowledge has to play in the creative process.

In many cases in the context of examining creativity in organizations, it is useful to explicitly distinguish between “creativity” and “innovation.”[26]

In such cases, the term “innovation” is often used to refer to the entire process by which an organization generates creative new ideas and converts them into novel, useful and viable commercial products, services, and business practices, while the term “creativity” is reserved to apply specifically to the generation of novel ideas by individuals, as a necessary step within the innovation process.

For example, Amabile et al. suggest that while innovation “begins with creative ideas, creativity by individuals and teams is a starting point for innovation; the first is a necessary but not sufficient condition for the second.” [27]

Economic views of creativity

In the early twentieth century, Joseph Schumpeter introduced the economic theory of “creative destruction,” to describe the way in which old ways of doing things are endogenously destroyed and replaced by the new.

Creativity is also seen by economists such as Paul Romer as an important element in the recombination of elements to produce new technologies and products and, consequently, economic growth. Creativity leads to capital, and creative products are protected by intellectual property laws. Creativity is also an important aspect to understanding entrepreneurship.

The “creative class” is seen by some to be an important driver of modern economies. In his 2002 book, The Rise of the Creative Class, economist Richard Florida popularized the notion that regions with high concentrations of creative professionals such as hi-tech workers, artists, musicians, and creative people and a group he describes as “high bohemians,” tend to have a higher level of economic development.

Creativity, music and community

Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania Social Impact of the Arts Project[28] found that the presence of arts and culture offerings in a neighborhood has a measurable impact on the strength of the community. Arts and culture not only attract creative workers, but also is a key element in the revitalization of neighborhoods, and increases social well-being. They also found that music is one of the key arts and cultural elements that attracts and retains “creative workers.” To slow down the large emigration of young cultural workers from Pennsylvania, this study proposed enhancing school-based music education and community-based musical cultural offerings. This study discovered the following traits in creative workers: individuality; creativity; technology and innovation; participation; project orientation; and eclecticism and authenticity. They found that music education helps foster all these traits to help Americans realize their creative potential. As a result, the author claimed, music education not only nurtures creativity but also plays a crucial role in the knowledge economy, and in strengthening communities.

Notes

C.W. Taylor, “Various approaches to and definitions of creativity.” in The nature of creativity: Contemporary psychological perspectives, ed. R.J. Sternberg, (Cambridge University Press, 1988. ISBN 0521338921)

M. Rhodes, 1961 “An analysis of creativity.” Phi Delta Kappan 42: 305-311

D.M. Johnson. Systematic introduction to the psychology of thinking. (Harper & Row, 1972. ISBN 0060433310)

M.A. Boden. 2004 The Creative Mind: Myths And Mechanisms. (Routledge ISBN 0465014518)

A. Koestler. The Act of Creation. (Macmillan, 1975 ISBN 0330244477)

Władysław Tatarkiewicz. A History of Six Ideas: an Essay in Aesthetics, Translated from the Polish by Christopher Kasparek, (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1980. ISBN 9024722330)

R.S. Albert, & M.A. Runce, “A History of Research on Creativity” in Handbook of Creativity, ed. R.J. Sternberg, (Cambridge University Press, 1999. ISBN 0521576040)

R.J. Sternberg, and T.I. Lubart, “The Concept of Creativity: Prospects and Paradigms.” Handbook of Creativity, ed. R.J. Sternberg, (Cambridge University Press, 1999 ISBN 0521576040)

G. Wallas. Art of Thought. (Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1926 ASIN B000GRK1P6)

D.K. Simonton. 1999 Origins of genius: Darwinian perspectives on creativity. (Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195128796)

T. Ward, 2003 “Creativity.” L. title=Encyclopaedia of Cognition, ed. L. Nagel, (New York, Macmillan)

S.M. Smith, & S.E. Blakenship, 1991 “Incubation and the persistence of fixation in problem solving.” American Journal of Psychology 104: 61–87

J.R. Anderson. 2005 Cognitive psychology and its implications. (Worth Publishers. ISBN 0716701103)

J.P. Guilford. The Nature of Human Intelligence. (McGraw-Hill ASIN B000IFVRKE)

R. Finke, T.B. Ward, & S.M. Smith, 1996 Creative cognition: Theory, research, and applications. (MIT Press. ISBN 0262560968)

R.W. Weisberg. 1993 Creativity: Beyond the myth of genius. Freeman ISBN 0716723670)

L.A. O’Hara, & R.J. Sternberg, “Creativity and Intelligence.” in Handbook of Creativity, ed. R.J. Sternberg, (Cambridge University Press, 1999)

Fred Balzac, 2006 Exploring the Brain’s Role in Creativity NeuroPsychiatry Reviews 7 (5): 1, 19-20

J.P. Rushton, “Creativity, intelligence, and psychoticism.” Personality and Individual Differences 1990 11: 1291-1298

Melanie Moran. Odd behavior and creativity may go hand in hand September 6, 2005.

T.M. Amabile, 1998 “How to kill creativity.” Harvard Business Review 76 (5)

K. Dorst, and N. Cross, 2001 “Creativity in the design process: co-evolution of problem–solution.” Design Studies 22 (5) :425-437

National Academy of Engineering. 2005 Educating the engineer of 2020: adapting engineering education to the new century. (National Academies Press )

Creative Industries Mapping Document 2001. an overview of creative industries in the UK.

I. Nonaka, 1991. “The Knowledge-Creating Company.” Harvard Business Review 69 (6): 96-104

T. M. Amabile, R. Conti, H. Coon, et al. 1996 “Assessing the work environment for creativity.” Academy of Management Review 39 (5): 1154-1184

Amabile et al., 1996: 1154-1155, (emphasis added)

Patrick M. Jones, “Music Education and the Knowledge Economy: Developing Creativity, Strengthening Communities.” Arts Education Policy Review (Mar/Apr 2005) 106 (4): 5-12, 3 charts

U. Kraft, “Unleashing Creativity.” Scientific American Mind 2005 (April): 16-23

R.R. McCrae, “Creativity, Divergent Thinking, and Openness to Experience.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology (1987) 52 (6): 1258-1265

D.H. Pink. 2005 A Whole New Mind: Moving from the information age into the conceptual age. (Riverhead. ISBN 1573223085)

R.S. Nickerson, “Enhancing Creativity.” Handbook of Creativity.

Swedish Morphological Society. Retrieved June 13, 2008.

quoted in Ian S. Markham. A World Religions Reader. (Blackwell Publishing, 2000. ISBN 0631215190)

Gleanings from the Writings of Bahá’u’lláh [1] bahai.org. Retrieved September 30, 2008.

Dirk H. Kelder. 1998. Nikolai Berdyaev. Retrieved June 13, 2008.

Alfred North Whitehead. Process and Reality. (New York: Free Press, 1979 ISBN 0029345707)

M.A. Runco, 2004 “Creativity.” Annual Review of Psychology 55: 657-687

D.H. Feldman, “The Development of Creativity.” Handbook of Creativity.

R.B. McLaren, “Dark Side of Creativity.” Encyclopedia of Creativity, eds. M.A. Runco, & S.R. Pritzker, publisher=(Academic Press. 1999 ISBN 0122270754)

BCA 2006. New Concepts in Innovation: The Keys to a Growing Australia. Business Council of Australia. Retrieved June 13, 2008.

4. References

Anderson, J. R. Cognitive Psychology and its Implications. Worth Publishers, 2005. ISBN 0716701103

Berdyaev, Nicolai. The Meaning of the Creative Act, Trans. by Donald A. Lowrie. Gollanz, 1955.

Boden, M. A. The Creative Mind: Myths And Mechanisms. Rutledge, 2004. ISBN 0465014518

Finke, R. T.B. Ward, and S.M. Smith. Creative Cognition: Theory, Research, and Applications. MIT Press, 1996. ISBN 0262560968

Florida, R. The Rise of the Creative Class: And How It’s Transforming Work, Leisure, Community and Everyday Life. New York: Basic Books, 2003. ISBN 0465024777

Guilford, J. P. The Nature of Human Intelligence. McGraw-Hill, 1967.

Johnson, D. M. Systematic Introduction to the Psychology of Thinking. Harper & Row, 1972. ISBN 0060433310

Koestler, Arthur. The Act of Creation. Macmillan, 1975. ISBN 0330244477

Kraft, U. “Unleashing Creativity.” Scientific American Mind (April 2005): 16-23.

Markham, Ian S. A World Religions Reader. Blackwell Publishing, 2000. ISBN 0631215190

Michalko, M. Cracking Creativity: The Secrets of Creative Genius. Ten Speed Press, 2001. ISBN 1580083110

Nickerson, R.S. “Enhancing Creativity.” In Handbook of Creativity, edited by Sternberg, R.J. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521576040

Pink, D. H. A Whole New Mind: Moving from the Information Age into the Conceptual Age. Riverbed, 2005. ISBN 1573223085

Runco, M. A. & S. R. Pritzker. Encyclopedia of Creativity. Academic Press. ISBN 0122270754

Simonton, D. K. Origins of Genius: Darwinian Perspectives on Creativity. Oxford University Press, 1999. ISBN 0195128796

Sternberg, R. J., Ed. The Nature of Creativity: Contemporary Psychological Perspectives. Cambridge University Press, 1988. ISBN 0521338921

Tatarkiewicz, Władysław. A History of Six Ideas: an Essay in Aesthetics, Translated from the Polish by Christopher Kasparek. The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1980. ISBN 9024722330

Torrance, E. P. Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking. Georgia Studies of Creative Behavior, 1974.

Weisberg, R. W. Creativity: Beyond the Myth of Genius. Freeman, 1993. ISBN 0716723670

Whitehead, Alfred North. Process and Reality. New York: Free Press, 1979. ISBN 0029345707

Joy Paul Guilford (March 7, 1897 – November 26, 1987) was an American psychologist, one of the leading American exponents of factor analysis in the assessment of personality. He is well remembered for his psychometric studies of human intelligence and creativity. Guilford was an early proponent of the idea that intelligence is not a unitary concept. Based on his interest in individual differences, he explored the multidimensional aspects of the human mind, describing the structure of the human intellect based on a number of different abilities. His work emphasized that scores on intelligence tests cannot be taken as a unidimensional ranking that some researchers have argued indicates the superiority of some people, or groups of people, over others. In particular, Guilford showed that the most creative people may score lower on a standard IQ test due to their approach to the problems, which generates a larger number of possible solutions, some of which are original. Guilford's work, thus, allows for greater appreciation of the diversity of human thinking and abilities, without attributing different value to different people.

Joy Paul Guilford, known as J. P. Guilford, was born on March 7, 1897 in Marquette, Nebraska. His interest in individual differences started in his childhood, when he observed the differences in ability among the members of his own family.

As an undergraduate student at the University of Nebraska, he worked as an assistant in the psychology department. While in graduate school at Cornell University, from 1919 to 1921, he studied under Edward Titchener. He conducted intelligence testing on children. During his time at Cornell, he also served as director of the university's psychological clinic.

Guilford retired from teaching in 1967, but continued to write and publish. He died on November 26, 1987 in Los Angeles, California.

Feedback/Errata