Readings

Bruno, Carmen: Digital Creativity Dimension

Chapter 1 –Introduction

Chapter 2 – The Variegate Scenario of Creativity Definitions

Chapter 3 – Evolving Creativity

Chapter 4 – The Creativity Domain

Chapter 5 – Perspectives to Explore Digital Creativity

Chapter 6 – References

1. Introduction

Digital Creativity Dimension: A New Domain for Creativity

With the world rapidly changing, creativity has become more fundamental than ever before. We live in a society where those who do not creatively innovate risk failure in any of several domains of life. With the growth of computational power of machines and the development of Artificial Intelligent systems, the centrality of humans in the future will strongly rely on their creativity skills that are therefore transforming from a sort of scientific singularity reserved to a few talented individuals to an essential ability for the entire human species.

According to Corazza (2017), creativity now will not only be accessible to everyone, but it will essentially be the prime skill and talent for all human beings. Therefore, it is fundamental to deeply understand the creativity phenomenon in all its multifaceted aspects, how it is evolving in the digital transition, and how it is possible to educate people to develop their creative thinking abilities and spread its practical application in all domains of knowledge.

The third chapter aims to show the variegated scenario of creativity definitions and the evolution of modern creativity studies, providing an overview of the various approaches and perspectives to the study of creativity, from the individual to the sociocultural and distributed perspectives emerging with the advent and spread of ICTs (Information and Communication Technologies). The chapter highlights the requirements emerging from the scientific community about the study of the new domain, named Digital Creativity, that is a widespread and unclear realm in rapid evolution and constant redefinition, where multiple disciplines already investigate the influences and relationship between creativity and digital technology from several and fragmented perspectives. The chapter provides a brief review of the main authors studying this domain, showing the two main perspectives identified to explore Digital Creativity from a design-oriented perspective.

2. The Variegate Scenario of Creativity Definitions

Creativity has been studied by psychologists, sociologists, neuroscientists, educators, historian, economists, engineers, and scholars of all types, and nowadays there is still a continuous growth of creativity studies applied in many fields such as education, innovation and business, the arts and sciences, and society as a whole (Florida 2014; Runco 2007; Simonton 1997).

The interest by many different disciplines has contributed to the development of a panoply of theories that conceptualize creativity from various different perspectives and approaches, highlighting its complex and multidimensional nature.

Defining creativity has been considered one of the most difficult tasks of the social sciences. The creativity concept is constantly changing and evolving according to the sociocultural environment around us (Runco 2017), many definitions—over 50—have been proposed (Runco 2004), and many more will be.

However, some authors have tried to formulate a shared definition to at least identify some pillars that give shape and direction to the phenomenon.

According to Kaufman and Sternberg (2010), most definitions of creative ideas comprise three main components that represents the basics: novelty—therefore creative ideas must represent something new or innovative; goodness—therefore creative ideas are of high quality; and relevance—therefore creative ideas must also be appropriate to the task at hand.

According to this perspective, a creative idea should be novel, good, and relevant.

This vision provides a description of creativity that is totally oriented to the output of the creative act.

In this direction, a largely accepted definition is the Standard Definition of Creativity that states that creativity requires originality and effectiveness (Runco and Jaeger 2012).

Original things must be effective to be creative, meaning that they have to be useful, appropriate, or, according to economic research on creativity, generate value based on the current market (Rubenson 1991; Rubenson and Runco 1992, 1995; Sternberg and Lubart 1991, as cited by Runco and Jaeger 2012). Simonton (2012) promoted the integration of non obviousness or surprise, besides novelty and utility.

Even if it’s widely recognized, the Standard Definition of Creativity has been criticized in particular by those researchers that address creativity studies from the sociocultural perspectives and stress the importance of the audience and the relationships that are inherent between the creative person, the creative process, and the audience itself (Amabile 1996; Csikszentmihalyi 1988; Glăveanu 2010).

Another critique comes from Corazza (2016) who maintains that the definition “fails to give a proper place to creative inconclusiveness, as well as to the abilities, traits, and contextual elements that are instrumental in increasing the chances to see the light at the end of this crucial part of the process” (p. 261).

He proposed that, at the core of the definition of creativity, there should be the search for potential originality and effectiveness because creativity is a dynamic rather than static phenomenon that requires cognitive and affective energy and a dynamic relationship with the environment.

He formulated a dynamic definition of creativity that states: “Creativity requires potential originality and effectiveness” (Corazza 2016), shifting the focus more on the creative process and on active engagement rather, than the creative achievement itself.

In creativity, as in many other areas of positive human activities, active engagement has a very important value in itself, even without achievement and/or recognition of success.

Creativity is intended also as an ability to discover something new, to adapt the available knowledge purposefully, and to solve the problems originally, flexibly, and effectively (Runco and Jaeger 2012). This definition treats creativity as a skill, while also paying attention to the mechanisms that occur within the creative act.

Poincare (1924) considered creativity as the ability to recognize the usefulness of new configurations of existing elements. He considered creativity as a skill that is based on the ability to “disconnect” and reconnect existing elements of knowledge to each other, by association, according to schemes never used before. The first reference to the multiphase structure of the creative process to solve mathematical problems belongs to him.

Wallas (2014), inspired by his work, speak about creativity in terms of creative process and provide a configuration in four mental phases: preparation, incubation, illumination, and verification. This classification was the starting point to define new models (Corazza and Agnoli 2015a, b; Dubberly 2004; Tassoul and Buijs 2007) to better describe process phases.

When defining creativity and innovation, it is essential to take into consideration the social, cultural and economic context in which we live. In fact, with human evolution, there are new domains in which creativity is often expressed, such as politics, digital technology, moral and everyday creativity (Runco 2017) that also led to the definition of new methodologies for its investigation (Williams et al. 2016) and new perspective through which the phenomenon is defined. For example, with the technological advancement there has been a boom in neuroscientific research on creativity thanks to new equipment for assessing creative potential as well as an employment for enhancing creative thinking (Benedek et al. 2006). Therefore the study of creativity must evolve along with the dramatic technology-induced transformations of society.

This means that actually there is no static definition of creativity, but it evolves over time since its judgments and manifestations fluctuate over time (Csikszentmihalyi 1990; Runco et al. 2016b; Runco et al. 2010, as cited by Runco 2017, p. 308), according to the domain in which it is applied and the perspective adopted for its study. The new technological domain has contributed to this variation, and Runco and Jaeger (2012) proposed that fluctuation should be expected of definitions.

Therefore, it’s fundamental to study and understand how creativity changes because it is a fundamental skill that can guide the human being throughout its evolution.

It is quite evident that the phenomenon of creativity involves many nuances and interpretations, and it is necessary to adopt a clear perspective for its studies to circumscribe the phenomenon. Also, the conclusion achieved by studying creativity may depend strongly on how terms are defined; a conclusion that appears true by one definition of creativity may simply not apply when another is used.

To make some clarification to how the definition and theories on creativity have evolved, the next session offers a brief historical review of the evolution of modern creativity research.

3. Evolving Creativity: From Creativity 1.0 to Creativity 4.0

The concept of creativity has its own history, taking an intellectual path that was for two centuries been independent of the institutionalization and conceptualization of research. At their beginnings and during most of their histories of development, research and creativity were not viewed as related to one another.

In 1869, Francis Galton offered the world, through his “Hereditary Genius”, the first scientific study of the creative genius (Simonton 2003) where creativity was seen as based on the individuality, insight, outstanding ability, and fertility of the isolated genius (Mason 2003). He gave an elitist and essentialist account of creativity (Negus and Pickering 2004, p. 81).

Modern creativity research began in the 1950s and 1960s. From that time until today, researchers have focused their studies on different aspects of creativity contributing to the creation of the rich baggage of knowledge that has cancelled the concept of creativity as an ability of an isolated genius.

Nowadays, creativity research can be grouped into two major traditions of research: an individualistic approach and a sociocultural approach. Each of them has its own distinctive analytic focus, and each of them defines creativity slightly differently.

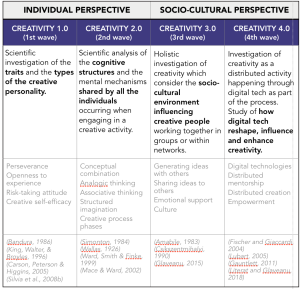

These approaches are based on years of research that can be mainly clustered in three waves of psychological studies—discussed within this section—that have enabled the evolution of different visions of the concept of creativity. They range from a first vision defined as creativity 1.0 (the first wave) where creativity research was focused on studying the personalities of exceptional creators; to a creativity 2.0 (the second wave) where researchers shifted their attention to the mental processes that occur while people are engaged in creative behavior; to a sociocultural, interdisciplinary approach, creativity 3.0 (the third wave) focused on the social dimension of creativity. Let’s explore in detail these waves.

Around the 1950s, a first wave of psychologists started to scientifically investigate the traits and the types of the creative personality. These psychologists adopted an individualistic approach to the study of creativity that defined creativity as “a new mental combination that is expressed in the world” (Sawyer 2012, p. 7).

According to the individualistic approach, the first wave of psychologists asserted that “creativity resides in the middle ground between ability and personality; it’s highly correlated with intelligence and yet it’s also associated with various personality traits” (Sawyer 2012, p. 63–64).

For psychologists in the 1950s and 1960s, creativity was synonymous with scientific creativity. They worked hard to develop tests to assess and identify children who were gifted and talented so that schools could nurture their talents and target them for high-creativity careers in science and technology (e.g. Parnes and Harding 1962, as cited in Sawyer 2012, p. 37).

One of the main voices in psychology of this first wave was that of Guilford, remembered for his historical APA presidential address in 1950. While calling the attention of psychologists to the topic of creativity, he also gave them a clear agenda: “the psychologist’s problem is that of creative personality” (Guilford 1950, p. 444) and “creative acts can therefore be expected, no matter how feeble or how infrequent, of almost all individuals” (Guilford 1950, p. 446). And Guilford’s message was heard: for the following decades, psychologists looked intensively for the personal attributes of individuals (personality, intelligence, etc.) and their links to creativity (Amabile 1996).

On the other hand, studies of the creative personality proved to be an even more fertile tradition. Among the most common traits encountered were: tolerance for ambiguity and orientation towards the future (Stein 1953); independence of judgment; preference for complexity; strong desire to create; deep motivation; strong intuitive nature and patience (Barron 1999); originality; and a good imagination (Tardif and Sternberg 1988).

In addition, perseverance, intellectual curiosity, openness to experience (Carson et al. 2005; King et al. 1996; McCrae 1987; Silvia et al. 2008, as cited by Sawyer 2012, p. 66), a risk-taking attitude, and self-efficacy (Bandura 1986) have been recognized as fundamental attitudes for the performance of creative activity and reaching original and novel results.

Around 1970, a second wave of psychologists started to study creativity in a different and new way (Feldman et al. 1994). Behaviorism and personality psychology were replaced by cognitive psychology that started to analyze the cognitive structures and the mental mechanisms, shared by all the individuals, occurring when engaging in a creative activity. They contributed to spread a more democratic view of creativity: All persons of normal intelligence possess some ability to think creatively and to engage themselves in imaginative and innovative efforts (Roth 1973).

“Psychologists have studied the creative process for decades, and they’ve observed that creativity tends to occur in a sequence of stages” (Sawyer 2012, p. 88). The first configuration of the creative process was proposed by Wallas (2014), which—as previously mentioned—divided the process into four phases. Sawyer (2012) proposed an integrated framework that captures the key stages of all the various models that psychologists have proposed (p. 89).

Indeed, process theories specify different stages of processing (e.g. Mace and Ward 2002; Simonton 1984; Wallas 1926; Ward et al. 1999, as cited by Kozbelt et al. 2010, p. 31) or particular mechanisms as a component of creative thought (e.g. Mumford et al. 1997; Mumford et al. 1991, as cited by Kozbelt et al. 2010, p. 31) such as conceptual combination, analogic thinking, associative thinking, structured imagination, and creative visualization (Ward et al. 1999).

What all these diverse approaches have in common is their attempt to relate creativity to something from within the psychology of the person. The two waves refer to an individualistic approach and are not opposed but complementary. They are both needed to explain this complex phenomenon. Both personality traits and attitudes and cognitive processes are still studied and explored today, continuously adding shades and nuances.

Around the 1980s, a third wave of researchers introduced a paradigm shift by adopting a new sociocultural approach to the study of creativity. They adopted a more holistic approach and studied creative people working together in cultural and social systems. Everyone is a member of many social groups, each one constituted by a network; everyone is a member of a culture and creates as a representative of a certain historical period (Glăveanu 2015). According to the sociocultural approach, the totality of this aspect contributes to influence and determine the creative potential of an individual (Amabile 1983).

The individual and social views are not mutually exclusive: Glăveanu (2015) maintained the social paradigm include the individualistic theory as part of creative complexity. An interdisciplinary approach is useful for the explanation of creativity.

Today, the emergence and development of digital applications, such as YouTube, Instagram, and Flickr, and the rapid penetration, in almost all aspects of our everyday life, of ubiquitous communication devices, such as smartphones and laptop, and the burgeoning of disruptive technology are providing new opportunities for creative expression, also a means of self-expression (Lassig 2012). Such tools enable people to express themselves in new ways, to make original and valued contributions, and to broaden opportunities for realizing one’s imagination (Loveless 2003). Those in the youngest generation have grown up with technology at their fingertips, and this probably has impacted the stimulus they need for expressing and releasing their creative potential.

Online participation has the potential to connect people and ideas, sharing information and facilitating collaboration also in the digital world.

These features not only impact creativity as a phenomenon but essentially redefine it “as the processes of creatively collaborating with others find themselves mediated by technological means” (Literat and Glăveanu 2016).

Digital technology and its influence are reshaping individuals and society from the human brain outwards and have established new norms for carrying out communication, work, and entertainment. Therefore, conventional definitions of creativity need to be redefined and reinterpreted from the perspective of digital technology.

The need to understand the digital impact on creativity has gained increased attention (Jackson et al. 2012; Schmitt et al. 2012; Zaman et al. 2010, as cited by Lee and Chen 2015, p. 12) giving birth to a fourth wave of study called creativity 4.0 where multidisciplinary researchers are investigating how creativity is evolving in the digital era and how it is influenced by the human, cultural, and technological evolution of this era.

The exploration of this wave sheds some light on a new domain called Digital Creativity. The next section provides an overview on the state of the art of this contemporary domain of study (Fig. 3.1).

4. The Digital Creativity Domain

“As digital innovation has permeated our daily lives, creativity has started to take a new shape: Digital Creativity” (Lee and Chen 2015). Lee (2015) provided one of the first definitions of Digital Creativity: ‘‘all forms of creativity driven by digital technologies’’. In other words, Digital Creativity occurs when any kind of digital device or digital technology is used for various creative activities.

This is a very wide definition considering that the concept of creativity spans a multitude of domains—from art to science to literature to business and beyond— and that the creative act is often mediated by digital tools, without even an awareness of using them.

The scientific literature on Digital Creativity is comprised of a range of multi- disciplinary contributions that makes clear the fragmented and distributed nature of knowledge and makes it difficult to read and understand the phenomenon as a whole.

Due to the very recent emergence of this concept, the scope, the perspective, and the main research themes of digital creativity studies are still not sufficiently clear.

The literature review published by Lee and Chen “Digital Creativity: Research Themes and Framework” (2015) tries to get some clarity out of it to facilitate the comprehension and study of digital creativity.

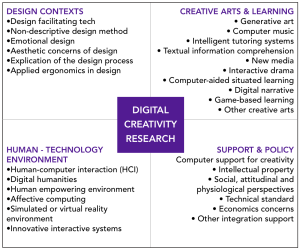

By analyzing 3591 pieces of relevant literature treating the topic of creativity and digital technology, they identified 20 major research themes—clustered in four categories—of digital creativity treated by multiple disciplines, such as computer science, social science, economics and business, art and humanities, and multi- disciplinary studies (Fig. 3.2).

Another fundamental reflection coming from this analysis is that Human Computer Interaction (HCI) Theme is the core of Digital Creativity research.

By approaching the HCI field, it emerges that one of the most recognized bodies of research has been done by Shneiderman (2000, 2002, 2007), Shneiderman et al. (2005). He has consistently undertaken studies on “Creativity Support Tools” (CST) that are intended as user interfaces or software supporting creativity across domains, empowering users to be more productive and more innovative.

The goal of CST is to make more people more creative more often, enabling them to face a wider variety of challenges creatively and successfully in many domains.

In 2005 he organized the workshop, “Creativity Support Tools” sponsored by the National Science Foundation, with the main aim of accelerating research on this topic and defining guidelines for the design and development of these tools.

According with the results obtained (Shneiderman et al. 2005), a CST should enable more effective searching of intellectual resources, improve team collaboration, and speed up creative discovery processes. They should also provide support in hypothesis formation, speedier evaluation of alternatives, improved under- standing through visualization, and better dissemination of results.

This Digital Creativity perspective from HCI is very much focused on the application of any kind of digital technology to develop a tool that could enhance and support some aspect of the creative process that allow individuals or teams to reach high levels of performance.

Another interesting article that follows this perspective is by Burkhardt and Lubart “Creativity in the Age of Emerging Technology: Some Issues and Perspectives in 2010” (2010). This was overview of progress in the HCI field in developing tools and digital spaces to support the individual and collaborative creative process, citing the major studies that has been done in the field.

A totally different perspective on the investigation and interpretation of Digital Creativity has been adopted by Zagalo and Branco in the book “Creativity in the Digital Age” (2015) and by Gauntlett in “Making is Connecting” (2011). They deal with the topic from a sociological point of view by observing the social and the behavioral changes occurring due to the increased diffusion of digital tools.

They share a common idea of creative technology intended as a means to help people find their own unique creative skills and to introduce them to the world, opening new dimensions for the facilitation of creativity by the broader population and, at the same time, making self-discovery possible.

New democratic digital technologies “have opened up complete new hands-on possibilities and, together with the social networks, have been crucial in creating community ties, to increase collaboration and participation, opening space for more elaborative creative technologies allowing in depth collaborative creation” (Zagalo and Branco 2015, p. 12).

These digital technologies make possible new avenues of widespread creativity by the general population, intrinsically motivated, but sharing a participatory culture made of content generated by all. They enable the creation of an open and free culture that is socially recognized and is built on the values of being part of a community.

A similar perspective has been pursued within psychological studies, however, with very few recent contributions. Surprisingly, the discipline of psychology, which, as we learned at the beginning of this chapter, has been responsible for the production of most of the scientific foundation of creativity, has practically almost not yet addressed the theme of Digital Creativity.

Two interesting contributions comes from Glaveanu and Literat: “Same but Different? Distributed Creativity in the Internet Age” (2016) and “Distributed Creativity on the Internet: A Theoretical Foundation for Online Creative Participation” (2018). They analyzed the evolution and spread of collaborative creative processes in the online environment, proposing a fresh perspective with which to study and analyze creativity in the digital age. They started from the observation of newly emerging social phenomena and human behaviors, such as the online presence and participation, and proposed the framework of distributed creativity to highlight some changes in the process of creation.

Also, Corazza and Agnoli “On the impact of ICT over the creative process in humans” (2015a, b) explore the opportunities that ICT technologies have opened for the general domain of creative processes. Many other articles have analyzed these opportunities in a specific domain, such as the work environment (Oldham and Da Silva 2016; Cabanero-Johnson and Berge 2009) or the educational context (Hoffmann et al. 2016).

Thanks to this brief overview of major recognized contributions, it is possible to assume that Digital Creativity is an evolving, growing discipline with great potential. It is a burgeoning phenomenon in rapid evolution and constant redefinition, where a dominant scientific thought has not yet been stratified and codified in theories and practices with references for those who approach this theme of research.

From this overview, two main perspectives clearly emerge for exploring this domain that can be considered as the two main directions to observe the influences that the digital age is bringing on human creativity. These are further discussed in the next section.

5. Perspectives to Explore Digital Creativity

Creativity has become, in our times, a sort of individual responsibility—everyone is required to cultivate his or her own creativity. In the digital age, creativity has been recognized as one of the most important human skills (The Partnership of 21st Century Skills 2008; World Economic Forum 2016) that can support people in facing the complex and continuous social, technological, and economic changes we are experiencing, offering a competitive advantage over others in a world dominated by the need to achieve and accumulate.

Creativity has become a democratic necessity (Corazza 2017), encouraging people to generate novel and useful ideas (Amabile 1988; Sternberg and Lubart 1999; Runco et al. 2012), helping them in manage the adoption of new digital technologies, taking advantage of their opportunities, and putting them at the service of the community in any field (Lee and Chen 2015).

It is therefore necessary to put human creativity at the centre of the digital transition because it is an increasingly essential skill for our survival in this era, especially in the necessary collaboration between humans and machines (Corazza 2017). Innovation today doesn’t solely rely on technology itself, but primarily on how it interacts with humanity, solving their problems, meeting their needs or challenges.

Empowering such an ability enables humans to acquire a maturity towards the evolution of digital technologies. Therefore, for design research, exploring and understanding Digital Creativity is a gateway to identify the evolved human factors for creative empowerment and how digital technologies can support and enhance them.

As shown in the previous section, a preliminary investigation of the domain sheds light on two different perspectives that are important to distinguish to deeply understand and achieve Digital Creativity.

The first perspective analyses the concept of creativity in the digital age that encompass the study of how creativity is understood in a time where more and more practices and work settings are becoming digitalized. This perspective is mainly adopted within the psychological and sociological fields that address the theme from a human point of view by observing the behavioral, social, and cultural changes related to the adoption of a diffused creative behavior. They observe and theorize about the new creative languages born with the introduction, diffusion, and adoption of digital technologies, how this will change culture and the new real possibilities and threats that all these changes represent for human creativity, and all the impact it can have on human life. According to this perspective, the new creative technologies are “forming the ground for the next great cultural movement giving voice to user’s wishes to express inner feelings, ideas, and visions; trans- forming; and giving shape to whatever imagination can generate” (Zagalo and Branco 2015, p. 2).

According to this perspective, the expression of creativity doesn’t always imply the use of a digital tool.

The second perspective can be defined as digitally supported creativity that encompasses the study of how creativity can be supported and enhanced by digital technologies but also how creativity can be transformed and become yet more digital. Technologies for Digital Creativity support many different kinds of artwork in digital representation (text, layout, image, sound, 3D object, moving image, etc.), as well as new forms of art such as generative art. The technologies also enable us to capture, store, manipulate, and output these representations to produce media forms we can experience.

This perspective is mainly adopted within the computer science field and the HCI domain that addresses the theme from a technological perspective testing and studies the application and potentialities of specific digital technologies for creative achievement.

Within this paradigm, the expression of creativity always implies the use of a digital tool.

These two perspectives are not so separate in reality and are not mutually exclusive. They represent different starting points with which Digital Creativity can be studied and investigated, as well as two discrete containers to explore the production of knowledge in this field.

Acknowledging these different viewpoints enhances understanding that the study of Digital Creativity also includes the study of the human being and the social and cultural changes within digital age that could affect creativity.

A typical example is social networking, considered as a new mindset where individuals connect to others online and can access a plentiful store of relevant information, enabling them to more effectively focus on targeted issues and themes. Today the process of creating involves a continuous movement across analog and digital and across the real and virtual.

The identification of the two perspective represents a way to achieve the first level of organization in the domain. To move further in the exploration and understand the evolution of creativity and the role of digital tools, it is fundamental to define a creativity frame, by interconnecting existing approaches (Rhodes 1961; Runco 2004; Kaufmann and Sternberg 2010), and confront it with the cognitive, behavioral, technological human changes brought by the digital transition as observed in Chap. 2. This creativity frame is fundamental for a structured exploration of Digital Creativity with a design-oriented vision. Its definition is explained in detail in Chap. 4.

6. References

Amabile, T.M.: The social psychology of creativity: a componential conceptualization. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 45(2), 357 (1983)

Amabile, T.M.: A model of creativity and innovation in organizations. Res. Org. Behav., 123–167 (1988)

Amabile, T.M.: Creativity and innovation in organizations. In: Harvard Business School Background Note, pp. 239–396 (1996)

Bandura, A.: Social foundations of thought and action: a social-cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ (1986)

Barron, F.: All creation is a collaboration. In: Montuori, A., Purser, R. (eds.) Social Creativity, 1, pp. 49–59. Hampton Press, Cresskill (1999)

Benedek, M., Fink, A., Neubauer, A.C.: Enhancement of ideational fluency by means of computer-based training. Creat. Res. J. 18, 317–328 (2006)

Burkhardt, J.M., Lubart, T.: Creativity in the age of emerging technology: some issues and perspectives in 2010. Creat. Inno. Manag. 19(2), 160–166 (2010)

Cabanero‐Johnson, P.S., Berge, Z.: Digital natives: back to the future of microworlds in a corporate learning organization. Learn. Org. 16(4), 290–297 (2009)

Carson, S.H., Peterson, J.B., Higgins, D.M.: Reliability, validity, and factor structure of the creative achievement questionnaire. Creat. Res. J. 17(1), 37–50 (2005)

Corazza, G.E.: Potential originality and effectiveness: the dynamic definition of creativity. Creat. Res. J. 28(3), 258–267 (2016)

Corazza, G.E.: Organic creativity for well-being in the post-information society. Europe’s J. Psychol. 13(4), 599–605 (2017)

Corazza, G.E., Agnoli, S.: On the impact of ICT over the creative process in humans. In: MCCSIS Conference 2015 Proceedings, Las Palmas De Gran Canaria (2015a)

Corazza, G.E., Agnoli, S.: Multidisciplinary Contributions to the Science of Creative Thinking. Springer, Singapore (2015b)

Csikszentmihalyi, M.: Society, culture, and person: a systems view of creativity. In: Sternberg, R. J. (ed.) The Nature of Creativity, pp. 325–339. Cambridge University Press, New York (1988)

Csikszentmihalyi, M.: Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. Harper & Row, New York (1990)

Dubberly, H.: How Do You Design. A Compendium of Models. Dubberly Design Office (2004)

Feldman, D.H., Csikszentmihalyi, M., Gardner, H.: Changing the World: A Framework for the Study of Creativity. Praeger, Westport, CT (1994)

Florida, R.: The Rise of the Creative Class, Revisited. Basic Books, New York (2014)

Gauntlett, D.: Making is Connecting, The Social Meaning of Creativity, from DIY and Knitting to YouTube and Web 2.0. Polity Press, Cambridge (2011)

Glăveanu, V.P.: Paradigms in the study of creativity: introducing the perspective of cultural psychology. New Ideas Psychol. 28(1), 79–93 (2010)

Glăveanu, V.P.: Creativity as a sociocultural act. J. Creat. Behav. 49(3), 165–180 (2015) 40 3 Digital Creativity Dimension: A New Domain for Creativity

Guilford, J.P.: Creativity. Am. Psychol. 5(9), 444–454 (1950)

Hoffmann, J., Ivcevic, Z., Brackett, M.: Creativity in the age of technology: measuring the digital creativity of millennials. Creat. Res. J. 28(2), 149–153 (2016)

Jackson, L.A., Witt, E.A., Games, A.I., Fitzgerald, H.E., von Eye, A., Zhao, Y.: Information technology use and creativity: findings from the children and technology project. Comput.

Hum. Behav. 28(2), 370–376 (2012)

Kaufman, J., Sternberg, R.: The Cambridge Handbook of Creativity. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK (2010)

King, L.A., Walker, L.M., Broyles, S.J.: Creativity and the five-factor model. J. Res. Pers. 30(2), 189–203 (1996)

Kozbelt, A., Beghetto, R.A., Runco, M.A.: Theories of creativity. In: Kaufman, J.C., Sternberg, R.

J. (Eds.) The Cambridge Handbook of Creativity. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK (2010)

Lassig, C.J.: Perceiving and pursuing novelty: a grounded theory of adolescent creativity. Doctoral dissertation, Queensland University of Technology (2012)

Lee, K.C.: Digital creativity: New frontier for research and practice. Comput. Hum. Behav. 42, 1–4 (2015)

Lee, M.R., Chen, T.T.: Digital creativity: research themes and framework. Comput. Hum. Behav. 42, 12–19 (2015)

Literat, I., Glăveanu, V.P.: Same but different? Distributed creativity in the internet age. Creat. Theor. Res. Appl. 3(2), 330–342 (2016)

Literat, I., Glaveanu, V.P.: Distributed creativity on the internet: a theoretical foundation for online creative participation. Int. J. Commun. (0), 893–908 (2018)

Loveless, A.: Creating spaces in the primary curriculum: ICT in creative subjects. Curriculum J. 14 (1), 5–21 (2003)

Mace, M.A., Ward, T.: Modeling the creative process: A grounded theory analysis of creativity in the domain of art making. Creat. Res. J. 14(2), 179–192 (2002)

Mason, J.H.: The Value of Creativity: An Essay on Intellectual History, from Genesis to Nietzsche. Ashgate, Hampshire (2003)

McCrae, R.R.: Creativity, divergent thinking, and openness to experience. J. Pers. Soc. Psych. 52 (6), 1258 (1987)

Mumford, M.D., Baughman, W.A., Maher, M.A., Costanza, D.P., Supinski, E.P.: Process-based measures of creative problem-solving skills: IV Category combination. Creat. Res. J. 10(1), 59–71 (1997)

Mumford, M.D., Mobley, M.I., Reiter‐Palmon, R., Uhlman, C.E., Doares, L.M.: Process analytic models of creative capacities. Creat. Res. J. 4(2), 91–122 (1991)

Negus, K., Pickering, M.: Creativity, Communication and Cultural Value. Sage Publications, London (2004)

Oldham, G.R., Da Silva, N.: The impact of digital technology on the generation and implementation of creative ideas in the workplace. Comput. Hum. Behav. 42, 4–11 (2016)

Parnes, S.J., Harding, H.F.: Preface In Parnes, S.J., Harding, H.F (Eds), A source book for creative thinking, v–viii, Charles Scribner’s Sons, New York (1962)

Poincare, H.: The Foundation of Science. Science Press, New York (1924)

Rhodes, M.: An analysis of creativity. Phi Delta Kappan 42(7), 305–310 (1961)

Roth, B.: Design process and creativity. Retrieved from https://dschool.stanford.edu/resources/bernie-roth-treatise-on-design-thinking (1973). Last accessed 15 Dec 2019

Rubenson, D.L.: On creativity, economics, and baseball. Creat. Res. J. 4, 205–209 (1991)

Rubenson, D.L., Runco, M.A.: The psychoeconomic approach to creativity. New Ideas in Psychology 10, 131–147 (1992)

Rubenson, D.L., Runco, M.A.: The psychoeconomic view of creative work in groups and organizations. Creat. Innov. Manage. 4, 232–241 (1995)

Runco, M.A.: Creativity. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 55, 657–687 (2004)

Runco, M.A.: Creativity: Theories and Themes: Research, Development, and Practice. Elsevier Academic Press, San Diego, CA (2007)

Runco, M.A.: Comments on where the creativity research has been and where is it going. J. Creat. Behav. 51, 308–313 (2017)

Runco, M.A., Jaeger, G.J.: The standard definition of creativity. Creat. Res. J. 24(1), 92–96 (2012)

Runco, M.A., Kaufman, J.C., Halladay, L.R., Cole, J.C.: Change in reputation as index of genius and eminence. Historical Methods 43, 91–96 (2010)

Runco, M.A., Acar, S., Kaufman, J.C., Halliday, L.R.: Changes in reputation and associations with fame and biographical data. J. Genius. Emin. 1, 52–60 (2016b)

Sawyer, R.K.: Explaining Creativity: The Science of Human Innovation. University Press, Oxford (2012)

Schmitt, L., Buisine, S., Chaboissier, J., Aoussat, A., Vernier, F.: Dynamic tabletop interfaces for increasing creativity. Comput. Hum. Behav. 28(5), 1892–1901 (2012)

Shneiderman, B.: Creating creativity: user interfaces for supporting innovation. ACM Trans. Comput. Hum. Interact. 7(1), 114–138 (2000)

Shneiderman, B.: Leonardo’s Laptop: Human Needs and the New Computing Technologies. MIT Press, Cambridge, UK (2002)

Shneiderman, B.: Creativity support tools: Accelerating discovery and innovation. Commun. ACM 50(12), 20–32 (2007)

Shneiderman, B., Fischer, G., Czerwinski, M., Myers, B.: Creativity support tools. In: National Science Foundation Workshop Report, pp. 1–83 (2005)

Silvia, P.J., Winterstein, B.P., Willse, J.T., Barona, C.M., Cram, J.T., Hess, K.I., et al.: Assessing creativity with divergent thinking tasks: exploring the reliability and validity of new subjective scoring methods. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts 2(2), 68 (2008)

Simonton, D.K.: Genius, creativity, and leadership. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA (1984)

Simonton, D.K.: Creative productivity: a predictive and explanatory model of career trajectories and landmarks. Psychol. Rev. 104(1), 66 (1997)

Simonton, D.K.: Creative cultures, nations, and civilizations: Strategies and results. In: Paulus, P., Nijstad, B. (eds.) Group Creativity: Innovation Through Collaboration, pp. 304–325. Oxford University Press, New York (2003)

Simonton, D.K.: Taking the U.S. patent office criteria seriously: a quantitative three-criterion creativity definition and its implications. Creat. Res. J., 97–106 (2012)

Stein, M.: Creativity and culture. J. Psychol. 36, 311–322 (1953)

Sternberg, R.J., Lubart, T.I.: An investment theory of creativity and its development. Hum. Dev. 34(1), 1–31 (1991)

Sternberg, R.J., Lubart, T.I.: The concept of creativity: Prospects and paradigms. In: Sternberg, R. J. (ed.) Handbook of Creativity, pp. 3–15. Cambridge, New York (1999)

Tardif, T.Z., Sternberg, R.J.: What do we know about creativity? In: Sternberg, R.J. (ed.) The Nature of Creativity, pp. 429–440. Cambridge University Press, New York (1988)

Tassoul, M., Buijs, J.: Clustering: an essential step from diverging to converging. Creat. Inno. Manage. 16(1), 16–26 (2007)

The Partnership of 21st Century Skills.: 21st Century Skills, Education & Competitiveness. A Resource and Policy Guide (2008)

Wallas G.: The Art of Thought, 1st Ed. 1926. Solis Press (2014)

Ward, T.B., Smith, S.M., Finke, R.A.: Creative cognition. In: Sternberg, R.J. (ed.) Handbook of Creativity, pp. 189–212. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1999)

Williams, R., Runco, M.A., Berlow, E.: Mapping the themes, impact, and cohesion of creativity research over the last 25 years. Creat. Res. J. 28, 385–394 (2016)

World Economic Forum.: The future of jobs: employment, skills and workforce strategy for the fourth industrial revolution (Report), Switzerland. Retrieved from http://www.weforum.org/reports/the-future-of-jobs (2016). Last accessed 20 Dec 2019

Zagalo, N., Branco, P.: Creativity in the Digital Age. Springer-Verlag, London (2015)

Zaman, M., Anandarajan, M., Dai, Q.: Experiencing flow with instant messaging and its facilitating role on creative behaviors. Comput. Hum. Behav. 26(5), 1009–1018 (2010)

Feedback/Errata