Readings

Moore, Brian: Music, Aesthetics, and Elements

This chapter focuses on four topics:

“Music expresses that which cannot be put into words and that which cannot remain silent” – Victor Hugo

Meaning in Music – Introduction

Music is an art form which exists in time. As a temporal art, it involves both sound and silence. While such sound and silence occurs in everyday life, it is when that sound is purposefully organized with intent of expressive effect that we begin to hear and think of it as music. So given a definition of music as purposefully organized sound for expressive intent, the nature of sound itself and how we perceive sound becomes most important.

The scientific study of sound (acoustics) does impact on our perception of sound, and we will delve into that later in this chapter. For now, our concern with sound is the various ways we perceive sound as music which typically involves some aspect of recognizing patterns and/or sources (instruments).

While obvious, it is important to note that one cannot hear an entire piece of music at once, since the sounds are presented in a linear fashion through time. In contrast, a piece of visual art (such as a painting) can be viewed in its entirety in an instant. (A photograph of a painting attempts to do just that.)

Given the fact that one hears a piece of music over a certain length of time, memory becomes crucial to the enjoyment and/or appreciation of that piece. You, as a listener, must remember what you heard a moment ago so that what you are hearing now makes sense and has meaning for you. In a similar fashion, the sounds you are about to hear will be compared to this set of aural remembrances. If you lack experience with the sounds you hear, or if you have little understanding or knowledge about what you are listening to, your initial reaction may be that you are hearing static or noise.

The Music 1 example “Noise” will probably be heard as nothing more than a sound effect or some kind of sound texture that might be a backdrop for something else.

If you recognize the sounds or sources, but they lack context or obvious organization, the results may sound as if they are random or by chance.

The Music 2 example “Sounds” are recognizable sounds, but still don’t resonate with our hearing as ‘music’. On first hearing, you might not be able to identify what the sounds are, other than three different sources one after another. Because of a lack of structure (i.e. no repetition or apparent organization) the entire example doesn’t convey strong musical ideas.

Your past experience and knowledge will also come into play when listening (and remembering) a piece of music. If for example you were to listen to a Japanese folk tune, and had little or no past experience and knowledge of how such music sounds, it might indeed sound like a foreign language. While you would ‘hear’ the sounds, there would be little meaning for you. What is happening is that you do not know what to expect as you listen to these new sounds. Since you don’t know what ‘normally’ happens. you are not able to react to instances of uniqueness, craftsmanship, or creativity within the musical work.

Imagine listening to a symphony by Mozart or a tune played by a rock ‘n’ roll band as compared to listening to static or ‘white noise’. While all these examples are sounds, the static/white noise does not have sufficient structure for you to remember, thus it will have little or no meaning for you.

Meaning in music has been described as involving expectation and the fulfillment of these expectations. Most people are familiar with the idea of musical style, either from past experiences in listening, or through an understanding of the history and theory of music.

The Music example “Guitar” has lots of inherent musical structure as well as a musical style that should be familiar. The piece will make sense to you as a piece of music even though it is something you’ve never heard before.

| Music Example 3: Guitar |

|

If one were to listen to a keyboard piece by the famous Baroque era composer Johann Sebastian Bach, there are certain things we would expect and other things we know would not occur. (We would not expect to hear a Dixieland chorus in the middle of a Bach organ prelude!) Compare the Bach ‘Giga (original)’ with the version that has ‘Mixed Styles’. You simply don’t expect the juxtaposition of so many musical styles in a single piece.

We can appreciate the craftsmanship contained in a Bach fugue, a Beatles tune, or a Duke Ellington song. Within any piece of music from any time period or style, we have certain expectations and then react to the manner in which our expectations are fulfilled or thwarted.

Memory, knowledge, and past experience all are involved when we listen to a piece of music. It would follow that our ability to listen can be enhanced by increasing our knowledge about music (both in general and specifically for a given piece) as well as broadening our experiences with the various aspects of music and music-making.

| Bach – Partita No. 1 in B flat Major, BWV 825 (excerpt) |

|

| Partita with variations of styles! |

|

So what about your background and experience in music? The music industry tracks music consumption in the form of sales of physical products (vinyl, CD), digital downloads (tracks as well as albums) and streaming. Here is a listing of the categories of musical style that are typically used to explain and detail such sales:

- Children

- Christian/Gospel

- Classical

- Country

- Dance/Electronic

- Holiday/Season

- Jazz

- Latin

- New-Age

- Pop

- R&B/Hip-Hop

- Rock

- World

style vs. genre

These terms are often mis-used. ‘Style’ refers to the particular manner in which a piece of music is performed or played (i.e. jazz style, baroque style, pop style) whereas ‘genre’ are units of compositions or categories of types of pieces such as ‘song’, ‘ballad’, ‘symphony’, or ‘musical’.

While some of the musical styles are very broad, it does provide a starting point for describing various styles (rather than genres) of music.

Here is a interactive slideshow that will present to you what percent of music sales for 2023 were in various categories. Before you try it, guess what you think might have been the top styles…

Link to the data used to create the above interactive slides.

Questions…

- What are examples of musical genres?

- What are examples of musical styles?

- What are other examples of arts that are temporal?

“Where words leave off, music begins.” – Heinrich Heine

Introduction to Aesthetics

Given the idea that meaning in art only comes if we, as the perceiver, have sufficient knowledge (expectations) and experience so as to ‘make sense’ of the artwork, it would follow that if our expectations are too easily met, aesthetic or artistic meaning will be at a very elementary and superficial level.

In an aesthetic experience, we need an artwork (a piece of music), and a perceiver (you as listener/performer). You perceive the artwork and then have reactions to it. (This is also a description of basic ‘survival’ perception – you see a red light, so you stop. When it turns green, you proceed.) What makes for aesthetic perception is the continuous and cyclical reactions/perceptions. Your reactions to the artwork now affects and changes your perceptions, giving you ‘newer’ perceptions and hence a new set of reactions. This give and take process continues between the artwork and yourself. Obviously, this process takes time and involves energy, feelings, emotions, (and sometimes effort!)

The quality of your perceptions/reactions are in part dependent upon your experiences and knowledge (as discussed earlier) and your attitude towards the specific aesthetic experience. The context or environment can play a crucial role. For example, one usually does not ponder and react over a piece of office furniture. However, if you were at a gallery, and, as an exhibit, the same piece of furniture was presented, you would approach the experience of looking at it differently – you would have a more ‘aesthetic’ approach.

Watch the next video for an example where a photo trying to capture a beautiful natural setting could yield an aesthetic experience. The more the person perceives the thing, the greater the quality and quantity of reactions. As the cycle of perception/reaction continues, the greater the potential for an aesthetic experience that improves in quality.

Aesthetic Perception & Reaction

Approaches

We can summarize various positions or approaches to any perceptual situation as (1) technical, (2) practical, (3) religious, and (4) aesthetic. The technical approach enters the listening of music with a concern as to the ‘how’ of the performance and matters related to the technical side of music. An individual who is studying piano and listening to a performance of a Beethoven piano sonata might attend to the fingering used by the artist, or the manner in which his or her sparkling technique must have taken years to develop. The analysis of music from a theoretical perspective could be included here.

Music perceived via a practical approach is usually secondary to some other occurrence. The music in elevators or doctors’ offices is not intended to demand our full attention, but rather as background. The dentist doesn’t want you to be expending energy listening to acid rock in anticipation of having a molar drilled! Music for special ceremonies or sporting events is used to serve a purpose, thus one does not usually associate such events as aesthetic in nature. In such situations while there usually is music, it is designed to be low in the need for effort in its perception as well as low in the thwarting of expectations. The music is typically not the focal point.

A religious approach to the listening of music is a response which does not focus upon the expressive qualities of the music itself, but rather to ideas, concepts or feelings associated with religious aspects, especially when lyrics/text is involved.

An aesthetic approach is one where the expressiveness of the elements of music form the basis for the perception – reaction cycle. It is this approach about which we want to continue our discussion.

The quality of your perceptions/reactions will also be dependent in part on the quality of the artwork itself. If your expectations are constantly met, the net effect will be boredom. Compare a Beethoven symphony with a simple pop tune. The symphony has much more content of greater complexity than what one typically hears in popular music. The relative simplicity of a pop tune is what helps to make it popular – it is easy to listen to, understand, and remember, and often after only a few hearings. An artwork needs a careful balance of structure, unity, and expected ‘norms’ with contrast and ‘surprises’.

Very serious contemporary music is sometimes of such a complex nature and structure, that it demands an incredible amount of previous knowledge and experience to fully react to all that the piece has to offer. Such intensity is very often beyond the desires of the average listener.

Here are some pieces presented in order of complexity to the listener (least complex first) – Notice that they were all composed around the same time period in history.

| Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On – composed 1957 |

|

| Theme from Star Trek (composed 1966) |

|

| Mambo from West Side Story: Symphonic Dances (composed 1960) |

|

| Atmosphères (for large orchestra) (composed 1961) |

|

Questions…

- Do you agree that these pieces are in order of complexity? Why or why not?

- Without using titles, or composer names, and without singing anything, how could you describe each piece so that someone who has heard them would recognize the one you’re talking about?

Aesthetic Approaches

Within the aesthetic approach to listening, there exists various theories as to how aesthetic perceptions and reactions are developed. One such view, referentialism, holds that the value of music lies in its reference to things outside and beyond the music itself. The Fantastic Symphony by Hector Berlioz is an example of a musical work conceived by the composer to be closely linked to a story. This story line is considered so important that the composer instructed that whenever the symphony is performed, the story should be printed in the audience’s program.

An opposite view, that of formalism, holds that the value of any musical work are the ideas expressed by the composer. Furthermore, these ideas are primarily of a purely musical nature.

The middle ground between these two extremes is that of absolute expressionism which accepts the value of the formal properties of a work of art, but also holds the notion that such properties may need to be considered relative to some non-musical aspect of human life.

The major function of art is to make objective, and therefore conceivable., the subjective realm of human responsiveness. Art does this by capturing and presenting in its aesthetic qualities the patterns and form of human feelingfulness… Aesthetic education, then, can be regarded as the education of feeling. (Reimer, a philosophy of music education, 1970:39).

Views of Musical Perception

Since perception is at the heart of an aesthetic experience, some discussion of how we perceive is helpful. Perception is often different from reality as can be shown by optical illusions. We organize our perceptions, especially those that are auditory, based in part on our past experience and our present knowledge.

Let’s look at a few illustrations regarding visual perception and then make the connection to aural and musical perception.

We make connections and sense relationships through our perceptions via concepts such as closure, proximity, and common fate. Let’s listen to excerpts by two composers, Ludwig van Beethoven (Symphony No. 5 in C minor) and Johann Sebastian Bach (Giga from Partita No. 1 in B flat Major, BWV 825).

Listen to this excerpt and answer the question…

Is this audio clip major or minor?

If you said minor, your past experience is probably at work as indeed, this is a pretty famous piece. It is by Ludwig van Beethoven and is his Symphony No. 5 in C Minor. So yes, the piece is in minor, but the clip is actually neither as insufficient melodic content is present to determine major vs. minor.

Here’s a score snippet of the opening five measures.

The orchestra is in unison, and only play four pitches: G Eb F D. These pitches on their own don’t indicate C minor (there is no C) nor Eb major. But you’ve heard the piece enough times that your past experience hears C minor. Your ears have “filled in the gaps” of ‘missing notes’ that would indicate major vs. minor as an aural example of ‘closure’.

The orchestra is in unison, and only play four pitches: G Eb F D. These pitches on their own don’t indicate C minor (there is no C) nor Eb major. But you’ve heard the piece enough times that your past experience hears C minor. Your ears have “filled in the gaps” of ‘missing notes’ that would indicate major vs. minor as an aural example of ‘closure’.

To make this point, note that the opening bars could have been written moving to either Eb major or C minor as you can hear in these contrived examples in the following video…

In the actual opening of the symphony, the real key of C minor doesn’t appear until the 7th measure when the bassoon and cello enters playing a C which is the tonic note.

Proximity / Common Fate

Here is an example of both proximity and common fate that we heard in a previous section. While the piece is written for a single keyboard player, you will be able to hear three parts: (1) a melody line consisting of short (often only two note) phrases, (2) a bass line that mirrors the melody line and (3) a middle range triplet accompaniment.

This version is played on the piano while the video version (with notation) has been realized on a synthesizer, using different timbres (instruments) to help you hear the three different parts. The closeness of the pitches in terms of range (proximity) as well as the contour of the musical phrases (common fate) help to provide this sense of multiple parts within a single piece.

Questions…

- Can you think of musical examples that demonstrate “closure”, “proximity” and/or “common fate”?

Music Perception

Our perception of sound is based on the physics behind sound as well as our physiological makeup as human beings. We have already talked about concepts such as “proximity”, “closure” and “common fate” and how they have an impact on how music is composed and heard. As a tangent, let’s look (and listen) to these concepts at work in a different context.

You are probably familiar with optical illusions, but did you know there are also auditory illusions as well? Let’s look and listen to a few…

Musical Illusions

Diana Deutsch is a psychologist who researched audio perception. Her work includes many auditory illusions

Let’s look at one so that as you understand what is happening, you might begin to think on how we hear might influence your upcoming musical and compositional decisions…

Scale Illusion

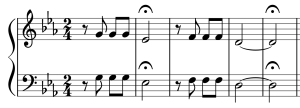

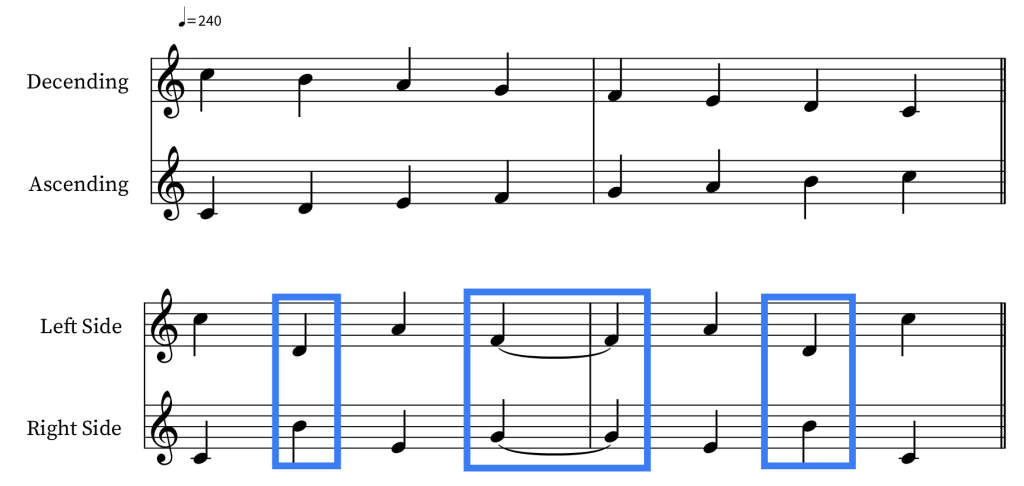

The Scale Illusion was discovered by Deutsch in 1973, first reported at a meeting of the Acoustical Society of America (1974) and first published in the Journal of the Acoustical Society of America (1975). The pattern that produces the Scale Illusion consists of a major scale with successive tones alternating from ear to ear. The scale is played simultaneously in both ascending and descending form; however when a tone from the ascending scale is in the right ear a tone from the descending scale is in the left ear, and vice versa.[1]

Here is how the audio file is created… left ear starts with a descending major scale and with right ear, an ascending scale. Then every other note is switched between ears (see the blue boxes.)

In the video below, I’ve created a version that plays the scale (1st line), then each modified scale one ear at a time (2nd line), and then finally the full illusion (both parts together).

Scale Illusion Demo

Even though the melodic content in each ear has lots of skips and jumps (is ‘disjunct’) our brain adjusts to provide a more ‘conjunct’ perception – most people will hear the descending part in the left ear, and the more ascending part in the right.

We perceive melody primarily through contour rather than individual pitches, thus our brains try to ‘smooth’ out the contour in this musical illusion.

To further demonstrate the strength of contour, here’s a well-know tune played with the correct pitches, but the contour (shape of the melody) has been inverted.

| Mystery Song (listen to this version first!) | |

| Original Song (in multiple octaves) |

The Power of Experience

Music is obviously an important aspect of your life as partly evidenced by your taking this course! Music in the 21st century is one of the most ubiquitous arts. We make connections across multiple mediums and arts in our digital environments.

Here’s a simple exercise to demonstrate this…

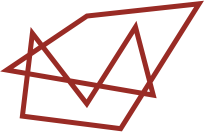

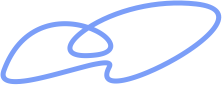

First, here are two made-up words:

- ooloom

- ta-ke-ti

Here are two abstract drawings:

So… which word goes with which picture? Pretty obvious but why? These shapes are pretty abstract (they don’t depict anything in particular) and the words are made up. Even the colors probably seem to agree with the pictures and words.

Listen to these pairs of musical examples… for each example, which would you label as “ooloom” and which as “ta-ke-ti” ?

| Music Excerpt A | |

| Music Excerpt B | |

| Music Excerpt 1 | |

| Music Excerpt 2 |

Questions…

- Describe the musical features used in these excerpts that create a sense of either “ooloom”

- Now describe musical features used that created a sense of “ta-ke-ti”

The Elements of Music

We have talked and listened to music as being something that is expressive and emotional. To help you understand the ways in which music moves us so that you could create your own music, you need to understand how music ‘works’ – the theory behind music. Musicians actually will speak of music theory in the way that a novel writer might discuss grammar or syntax, or a professional athlete might study and work on technique.

Introduction

An artform can be viewed as consisting of interrelated elements. For example, visual art can be described as involving elements such as color, line, and shape. A movie can be broken down into elements such as character, plot, and dialog. Music also has elements which can be described both in scientific and artistic terms.

The study of the physical properties of sound (acoustics) involves concepts important to music as an artform. While each element can be scientifically measured, the more important aspect is each element’s ability to be expressive in an artistic sense.

We shall view music as involving the expressive elements of texture, timbre, rhythm, melody, harmony and form.

When composers and performers deal with the elements of music, they must balance each so as to create a work and performance which has similarity and contrast, expectation and surprise.

Texture – Timbre

Texture is an element of music that involves aspects such as the type of instrument/voice being used, as well as the number of instruments heard at one time. Under this element, we will also include timbre (the characteristic quality of a sound), articulation (the manner in which the sound begins and ends – attack and release), and of course texture (characteristic quality of sound combinations).

The quality of a sound is acoustically described as the sum of its frequencies and is given the name of timbre (pronounced ‘tam-ber’). Complex sounds (i.e. any traditional instrument) are really combinations of many frequencies, each called an overtone. The only instance where a sound is just its base frequency (also called the fundamental) is a sine wave and can only be created electronically.

Even though timbre involves sounds with more than one frequency, the ear does not perceive individual pitches, but rather one pitch (determined by the lowest frequency – the fundamental) with a particular quality. Thus a violin and a clarinet playing the same note have the same fundamental, but a different combination of frequencies above that fundamental.

When working with electronic sounds and songs, composers often spend a lot of time and effort in working on the timbres as well as the way these instruments are combined to form texture.

Overtone Series

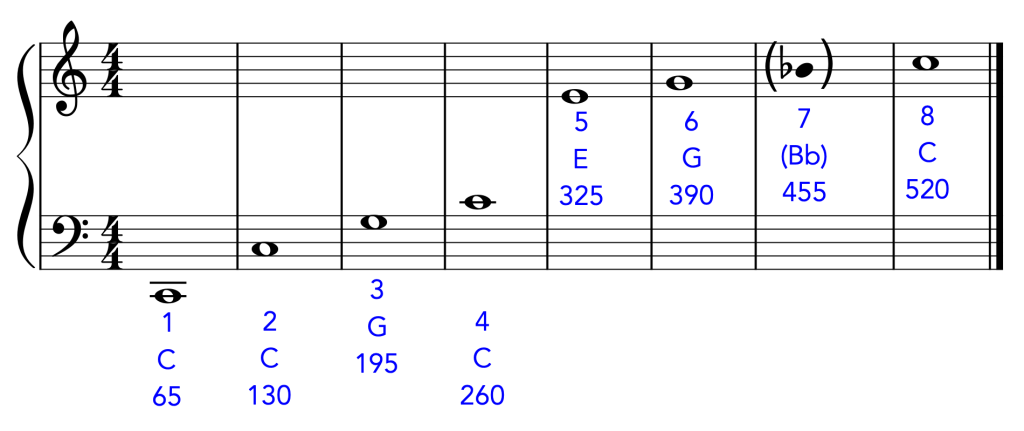

If we take a string that is say 10 inches, and pluck it we would get a sound. If we then cut the string in half (5 inches) and pluck it again, we would hear a pitch that is one octave higher than before (twice the cycles per second). There is a mathematical relationship between string length and frequency of sound heard which results in what is known as the overtone (or harmonic) series. A string’s frequency is inversely proportional to its length, thus if string X is one half of Y, its pitch will be twice that. Here’s what that would look like over 8 notes:

Look at the first three notes that have different pitch (letter) names – you’ll note them as numbers 1 (C) 3 (G) and 5 (E). This is exactly the same three notes if you were to create a chord, based in tertian harmony, starting on a C.

Practice: Logic Pro – Timbre & Software Instruments

Logic Pro comes with literally hundreds of software instruments which can be combined to create new timbres and textures.

- Start a new Project with “Empty Template”

- Choose “Software Instrument” for the initial track – be sure “Show Library” is checked

- Try out various software instruments

- Create additional tracks (use Track menu) with different instruments

- Use the NotePad to jot how you made the decisions you did..

Practice: Logic Pro – Texture & Track Stack Overview

- Start a new Project with “Empty Template”

- Add two tracks of different timbres

- Select the tracks and then use the “Stack Track” feature to create a summing track*

- Use the new track as a new patch.

*In Logic Pro, be sure Advanced Tools are on

Rhythm

In looking at rhythm as a musical element capable of meaning, we must discuss two aspects – beat (or pulse) as constant rhythm, and then the use of rhythm for musical ideas or motives (patterns). In non-musical settings, we tend to measure duration in units of time. The selection of the unit of measurement depends on the measurement scale we wish to use. For example, if one were to measure how long it takes to run the mile. we use the minute as the standard. We don’t speak of a .066 hour mile or the length of a class as lasting .0625 of a day. We select a unit of measurement which makes sense. The other concept to consider is that when measuring duration, there is a unit which becomes the standard. The unit of measurement does not change (i.e. a second today last as long as a second will tomorrow).

When duration is considered in a musical context, we again must have a standard unit of measurement. This standard is referred to as the beat or pulse. Most music around us has an underlying, constant pulse or movement, much the same way that our heart is constantly beating, even when we are unaware of its activity. The natural pulses of our body are excellent examples of tempo – constant, even measurements of time. Rhythmic pulse, both in nature and music, is never always at the same pace, but undergoes changes. If we are running, our heart beats faster – but still at a constant rate. The same is true when we are sleeping, for while our pulse is much slower, it is still a constant measurement of time.

Rhythmic Pulse

Tempo in music contains meaning for us as well as having certain expectations. Many people would equate slow music with relaxation, and fast music with excitement. While this is obviously an oversimplification, there is a bit of ‘common’ sense and experience to that idea. If musical pulse is viewed as a series of steady beats, given our discussion of expectation and perception, it would not have sufficient information for us due to its lack of structure and organization. Such a phenomenon would quickly bore the ear, as well as the composer and performer! We all tend to organize pulse around a meter, or the stressing of a specific pulse number. If every other pulse received stress (1 – 2 – 1 – 2), this would be considered duple meter. Every third pulse (1 – 2 – 3 – 1 – 2 – 3) would be triple meter. All music can be broken down or reduced to some combination of duple and/or triple meter. If the number of beats within a set, or measure is divisible by 2, then the meter is duple. Five beat measures could be conceived as one “submeasure” of duple plus one “submeasure” of triple. Some examples:

“Viennese Musical Clock” from Hary Janos Suite. The opening has bells which clearly outline a duple meter with four beats to the measure.

“Waltz” from Jazz Suite No. 2. This piece by a Russian composer uses a triple meter common in all waltzes. The accents on beat one can be clearly heard throughout the work, especially in the opening measures where basses play on beat 1 and the higher strings play beats 2 and 3.

“Mars, the Bringer of War” from The Planets. This movement has a meter involving five beats to the measure. This will note that it can be broken down to a 3 + 2 combination. The pulse is constantly driving. “Holst remarked that he wanted to express the stupidity of war: the pounding rhythm, occasionally giving way to a mindless swirling effect, admits of no compassion; the drive is as blunt as brutality itself”. (Notes by Richard Freed, program book of Saint Louis Symphony Orchestra)

We have only discussed so far rhythm in terms of a steady, unchanging standard of measurement or beat. Obviously, rhythm, if it is to be expressive, will need to involve sounds of various durations. Rhythm is usually conceived in terms of patterns upon which a piece is developed and or based. Rhythm in and of itself is expressive, and many pieces have been written which primarily focus upon the use of rhythm by contrasting even and uneven patterns of sound durations.

Practice: Logic Pro – Rhythm & DrumKits

Logic Pro has three percussion formats: MIDI drum kits, drum loops, and the interactive Drummer. For our purposes, we will focus on MIDI drum kits.

- Start a new Project with “Empty Template” using a software instrument for the initial track

- Change the instrument to a DrumKit

- Go to the editor, and on the left side you can view all of the different instruments in the kit

- Use “Step Sequencer” to control precise adding of drum hits via a grid into a ‘pattern region’

Harmony

Harmony is viewed as pitches heard all at the same time (vertical) as opposed to melody where pitches are hear in succession (horizontal). The historical period in which the music was written also will provide information as to the harmonic vocabulary of the piece. This element of music is the traditional focus of music theory courses, and in many instances, provides an underlying structure for a piece around which the other elements operate.

Tonal Center

When we hear a person say things like “That didn’t sound so good, are you in the right key?”, they are referring to the concept that one particular pitch or tone is the center around which all other pitches are structured. This tonal center can be considered the “main idea” in a melody in terms of the pitches which the composer uses. While every composer, including yourself, has 12 pitches available, seldom does he or she use all 12. (Imagine having to use every color available to you every time you created a painting). We shall look at a specific structure or system for selecting pitches called tonality.

Since we don’t want to get ahead of ourselves and discuss notation and vocabulary before we’ve had a chance to listen and think musically, let’s just say for now that the combination of tones we’ll use is simply all white keys of the piano (this is a major scale which we all know intuitively the sound of). We now have 8 instead of 12 notes available to use which we’ll number 1 through 8 and look like the following:

The first scale degree (in this case ‘C’) can be considered as the most important pitch in the same way that when we look at meter, we considered the first beat in each measure to be important and be stressed. The tonal center or tonic (scale degree number 1) is what is being talked about when a piece is said to be in a specific key. The Beethoven 5th Symphony in C Minor means that C is the tonal center and a minor (as opposed to major) scale is being used – more about scales later! As you listen to pieces which are tonal (99% of the music you hear around you!), you will notice how obvious the tonal center is to hear.

Organization

Some ground rules and assumptions are in order when we start talking about harmony (notes sounding at the same time). First, we are obviously talking about more than one note, and second, we usually assume that the notes are different. If I play two notes on the piano which I’ll call X and Y, and they are the same letter name but different octaves, we usually consider them to be, for the purposes of harmony, the same note. An octave can be described as the relation between the frequencies of two notes. If the ratio of cycles per second (cps) of X to Y is a multiple of two (1:2 or 1:4) then the two pitches will have the same letter name and differ only in their octave. For example, the pitch A at 440 cps is one octave above the A at 220 cps and 4 octaves above the A at 110 cps. Since the shape of the waves would complement each other, our ear perceives octaves as “pleasant” and sometimes as the same note.

A second ground rule is that two notes at the same time is called an interval while more than two notes is a chord. Note that we don’t need any further description (i.e. what kind of interval, or what kind of chord). If you place your entire arm on the piano and play 10 notes at once, it will still be a chord, and a very unique one at that!

Music of western cultures in the European and American tradition is built on tertian harmony or chords built on pitches that are three notes apart, counting the beginning note as one (i.e. A B C D E – 1 2 3 4 5). This system of harmony, as with the tonal center concept in melody, is one that you intuitively know through experience. Most of the music you listen to is this system of harmony.

Harmony as Vocabulary

The use of harmony by composers usually involves a certain harmonic style or vocabulary. We talk of a piece being major or minor – what we are referring to is the specific system of chords and harmonic vocabulary being used. It is possible to imagine that the number of possible chords is infinite, given that a chord is simply three or more notes at once. In practical terms, many, many combinations of chords are possible, but not all can be used. This is the same reasoning why in melody, we limit our choices from 12 notes to 8 as an organizing scheme. Historically, harmony has undergone great change and development as one’s ability to hear more complex chords improved. Let’s consider some examples.

An early piece such as the Canon in D by Johann Pachelbel is an excellent example of a work which uses a minimal harmonic vocabulary (8 chords). Each chord has only three different notes, and all would be found in the scale with D as its tonal center (D E F# G A B C# D).

Contemporary uses of harmony attempt to stretch the possibilities. One example is a piece by an American composer Charles Ives – Variations on America. At one point in the work, he needs to move from the Key of F major to the key of D-flat Major – these two keys are not related at all, so, he simply uses both keys at the same time to create a transition from one to the other. In the video, the music in the key of F is highlighted in red, and music in the key of D-flat in blue.

Practice: Logic Pro – Harmony & MIDI FX

There are several MIDI effects (MIDI FX) that can be helpful to experiment with various chords and harmonic progressions

- Select a track with a software instrument.

- Select the “Inspector” to reveal the control strip. (Also can be found in the View Menu as “Inspector”)

- There is a greyed out control labeled “MIDI FX” – try the following… For each, when you select a FX, a new window with controls will appear – input note(s), using either Musical Typing or an external device, to hear the effect

- Arpeggiator

- Chord Trigger

- Note Repeater

- Transposer

Melody

We can measure the highness or lowness of a sound by counting its vibrations or cycles per second (cps). While sounds can and do exist at all frequency levels, in music in the Western (European) tradition, only discrete frequencies are used. We typically think and hear melody as ‘the tune’ – and in lots of pop music, it is the melody that also has lyrics.

In the expressive sense, we can view melody as a succession of pitches, again with a degree of structure and contrast as well as expectations. We usually view melody relative to one pitch which becomes a standard, or ‘home tone’. This home tone (referred to as the tonic) is what is meant when we talk about a melody being in a certain key. The concept of a key or tonic is simply a form of structure – call any pitch the tonic, and immediately there exists a set of possible pitches to use in creating a melody.

An important aspect of melody is that of ‘contour’ – the overall shape of a melody. We actually hear shape and contour more than individual notes… Here’s proof!

Remember the “Mystery Song” from an earlier chapter? It was a demonstration of the importance of contour in melodies.

| Mystery Song (listen to this version first!) | |

| Original Song (in multiple octaves) |

Practice: Logic Pro – Melody & MIDI FX (Transposer)

In this practice session, we will ‘transpose’ an instrument so that it only plays notes in a specific scale to make sure a melody ‘fits’.

- Select a track with a software instrument.

- Select the “Inspector” to reveal the control strip. (Also can be found in the View Menu as “Inspector”)

- In the ‘info’ strip, select the MIDI FX popup and choose “Transposer”

- Use the Scale popup to change from Chromatic to Major (try others as well) – this transposes the keyboard or input device to ONLY use notes in the scale regardless of what you play!

Harmony and Melody as Related Elements

As we have seen so far, melody and harmony are related in as much as we can conceive of both involving pitch – melody the horizontal (linear) occurrence of pitches and harmony the vertical (simultaneous) occurrence of pitches. Now we want to discuss some ideas that are shared by both elements as well as reviewing some of the terms we have previously mentioned.

Tonality

Tonality refers to the organization of pitch around a central note (the tonal center). In practical terms, this is what we refer to when one talks about the key of a piece. A fundamental (and perhaps obvious) concept is that given any key, the same set of pitches is used when creating melody and harmony within the same piece. Contemporary composers have violated this concept as a way of writing atonal (not tonal) music by writing a melody in one key and using harmony, at the same time. in another. The overall effect is the “clashing” of two systems of organization resulting in two simultaneous tonal centers thus causing confusion to the ear.

Implied Harmony

Even though melody is horizontal and only one note at a time is heard, our ear, combined with our memory, can actually perceive what is referred to as implied harmony. We tend to remember, and then compare, the pitch we are currently hearing with what was just heard, and if the relationship is obvious enough, we can “hear” a specific chord. Prelude No. 1 in C from the Well-Tempered Clavier by J. S. Bach is an excellent example of implied harmony as even though only the first two pitches in each figure are actually held, one can clearly tell when the “harmony” changes. Another example is any typical bugle call. Because of the way the instrument is made, only notes that can be found in the overtone series are possible. (A bugle in B flat can only produce the notes in the B flat overtone series, etc.) Thus any melody played on a bugle is automatically organized around one pitch and therefore implies the tonic chord or harmony.

Another technique is that of rapidly alternating between notes common to a chord. Remember from our discussion of acoustics that notes 1, 3, and 5 from a scale together create a tonic chord (chord based upon the tonal center). Imagine a melody which only uses those three notes, but in rapid succession such as: 1 5 3 5 1 5 3 5 etc. Guitar players use this approach all the time when they are accompanying themselves. (This, by the way is not my invention! You can see (and hear) that such melodic patterns can indeed actually imply harmony.

So here’s a demonstration of this notion of melody implying harmony using the Prelude No. 1 in C that was mentioned earlier.

Form

Form refers to the structure of a given piece and will involve all of the elements of music we have mentioned. Form can be compared to the concept of a novel having a plot around which details occur. The plot provides the overall structure of the work and form in music functions in a similar manner. Again, historical periods of music developed and used specific forms, which follow patterns and conventions.

Popular Song Form

Popular music uses form to provide important repetition for the listener to learn the song quickly. Some of these sections can include:

Intro: often instrumental only which may also provide something that immediately captures the listener’s attention and sets up the feel or mode of the song.

Verse: The primary section of a song that ‘tells’ the story of the lyrics. Songs may have multiple verses with the only difference being the text (lyrics). Sometimes subsequent verses have slight differences in texture or accompaniment or key (verse 3 a half step higher for example)

Refrain: a line that is repeated at the end of each verse – often used to ‘connect’ to the Chorus.

Chorus: typically the ‘hook’ or most memorable part of the song, usually due to its simplicity, either in text or melodic construction. The chorus is the part of the song you’ll leave humming…

Bridge: an optional transition that usually occurs only once, near the end of the song. For example it may replace a verse in a ‘verse-chorus’ form, or between repeats of a chorus. It can also be an instrumental only ‘break’ with no lyrics.

Coda (or Extro): final part of a song, sometimes an instrumental version of the ‘hook’ from the chorus. Balances the ‘intro’ as the last thing the listener will hear.

Practice: Logic Pro – Form & Arrangement Track

The “Arrangement” Global Track easily lets you label, organize, and even rearrange the sections of your music.

- Start a new Project with “Empty Template”

- Use the Track menu to “Show Arrangement Track” – note the keyboard shortcut…

- Add sections using the ‘+’ button.

- Click the title of a section to change/edit it.

Note how the cursor changes depending upon where it is in the title bar of the section – you can shorten, lengthen, and/or move.

Final Thoughts

In our future discussions and experiences with these elements of music, it will be important for you to understand these ideas through ‘hands-on’ experiences of listening, performing and composing. In this, the interrelationships will become more apparent, and at the same time, will provide you with knowledge and experiences so that you can better shape the direction you would like to go in your aesthetic experiences with music.

refers to an artform that exists in time which would include music, dance, and theatre. Any piece of art that is temporal would have a duration/length

a set of principles concerned with the nature and appreciation of beauty, especially in art. Also a branch of philosophy that deals with the ideas of beauty and artistic taste.

a perspective on the aesthetic perception of art that the value of a musical work lies, in part, in its reference to things outside and beyond the music itself

a perspective of musical perception where the value of a musical work are the ideas expressed by the composer, primarily of a musical nature, with little or no external connections

accepts the formal properties of a work of art, but also holds that these properties may need to be considered within the context of non-musical aspects

tertian describes harmony, chords, or melody constructed from the intervals of thirds

two pitches played at the same time OR the distance between two pitches (such as a minor third, or a perfect fifth)

three or more notes typically sounding at the same time (but not required)

Feedback/Errata