Readings

Bennett, Stan: The Process of Musical Creation

THE PROCESS OF MUSICAL CREATION: INTERVIEWS WITH EIGHT COMPOSERS

Stan Bennett

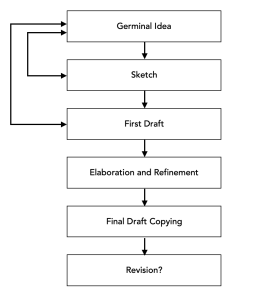

The process of musical creation was investigated through a series of semi-structured interviews with eight professional composers of classical music. For these eight composers, 12.1 years was the average chronological age when they composed their first work. For the majority of composers, the first composition was a song or melody. The composing process frequently involved first discovering a “germinal idea.” A brief sketch of the germinal idea was often recorded, followed by a first draft of the work, elaboration and refinement of the first draft, and then completion of the final draft and copying of the score. Compositional activity seems to occur most frequently in association with feelings of tranquility, security, and relaxation. Suggestions are presented for future research on the act of musical creation.

Key Words: aesthetic experience, aesthetic sensitivity, composing, creative activities, educational background, imagery, memory, musical experience.

Source: Journal of Research in Music Education, Vol. 24, No. 1 (Spring, 1976), pp. 3-13 Published by: Sage Publications, Inc. on behalf of MENC: The National Association for Music Education.

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3345061 .

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

The act of musical creation has been studied sporadically over the past 50 years. Sabaneev was one of the early researchers in the field.1 He reported that composers live in a world of tonal conceptions which are free of “will.” This tonal world resembles the dream life of the ordinary person. Conscious attempts to stimulate the tonal imagery are ordinarily futile, though improvisation may facilitate the process. Linking up various elements in a composition is often done with the concurrence of reason, according to Sabaneev.

The most extensive work on the musical composition process was done by Bahle during the 1930s.2 Bahle identified two types of composers – a “working type” and an “inspirational type.”3 The “working type” composer uses a preconceived plan, testing and correcting this through rational thought. The “inspirational type” composer, on the other hand, does little preplanning, relying instead on improvisation; the emotional impact of the work is anticipated as the piece is being composed.

Four basic steps in musical composition have been suggested by Graf.4 The first stage involves a productive mood – a condition of expectation that a composition is imminent. Composers frequently cycle in and out of productive moods, Graf notes. Improvisation may help initiate a productive mood, as may variables such as time of day or season of the year. The next stage in musical composition described by Graf is musical conception, when subconscious themes, melodies, or ideas break through to consciousness and are seized by the conscious mind. A sketch of the musical idea is often attempted at this time. Sketches are stenographic excerpts of the musical idea rather than finished pictures. The actual composing process involves condensation and expansion of the musical figures evoked during musical conception. Intellect is important across all stages of musical creation, but particularly during the actual composing process.

The present study reexamines and reinterprets some of the findings reported in earlier studies and attempts to identify some issues requiring further research.

Participants and Procedures

Eight professional composers of classical music residing in the Washington, D. C., metropolitan area participated in this study. The group was composed entirely of men.5 The music written by these eight composers is not what would presently be labeled as avant-garde, with one or two possible exceptions. Certainly they are not “chance” composers. Many compose linearly – that is, what occurs at the beginning determines to some extent what follows. One of these composers has begun to combine instrumental and electronic music; another has utilized music and film simultaneously.

A semistructured interview format was used in this study. The following questions were asked participants, generally in the order listed.

Can you recall when you first began composing? How did it happen? What stimulated it?

What kind of progression do you see in your music from the earliest to the present time?

Please describe in some detail the process by which you compose music.

Could you describe the conditions under which you composed your last piece of music?

What physical conditions seem to facilitate your composing?

What individuals have had the greatest impact on your music? What experiences have had the greatest effect on your music?

Are there particular emotional states that motivate you to compose? Are there some emotional states that seem to elicit your best compositions? Is there a predominant emotional theme in your music?

To what extent do you employ logic in composing? That is, is composing primarily a logical, deductive process for you, or is it a more spontaneous process?

Why do you compose? How do you see the impact of your music on the world? (Responses to these two questions were not analyzed in the present study.)

Probing questions were used when participants’ answers were not clear. Responses of participants were tape recorded with the exception of one person who asked not to have his comments recorded electronically.

The First Composition

All eight composers in this study indicated that they could recall their first composition. The mean age when the first composition occurred was 12.1 years, with a range of 4-22 years of age. A song or melody was composed in the case of five composers, a series of chords four bars long for one composer, and a “piano piece” by two others. (One composer did not describe the first composition.) The instrument composed for was usually the one available and most familiar to the composer (piano in four out of eight cases, a choral work in two instances, and a piece for trombone by a trombonist).

When asked what had stimulated the first composition, rather vague answers were provided. Three said they did not know. Others gave a variety of reasons, ranging from one composer’s response that it was just an overpowering urge to compose something to another person’s statement that at the age of five he knew he was a composer and therefore composing was a natural thing to do.

Development in Musical Composition

Next, the composers were asked to discuss the development of their music since the first composition. From the broad range of responses received, two things stood out – one dealing with changes in their music over time, the other having to do with the compositional training they received. Two composers mentioned that their music has become more complex and less dependent on earlier classical forms – more “far out.” Two of the composers in this study remarked that their music is less prone to youthful emotionalism than it used to be. Another trend seems to be toward greater conciseness – a tendency to distill and refine the music to its purest form. Half of the composers studied had some strong reservations about the composition training they had received. Comments like the following illustrate this point:

Although one teacher was a major force in the composer’s training in composition, the composer did not believe in the things he was taught.

One composer had a composition teacher who wanted him to learn what had been done by other composers,where as he just wanted to compose his own things.

When asked what effect studying with a well-known composer had had on his music,one composer said,”He deflected me briefly from my proper course.”

Still another composer said that until he went to college he wrote spontaneously and rapidly.He took harmony and counterpoint in college, where he was told that what he was doing was wrong. From that point on he would write a chord and then say to himself, “I’d better screw it up a little bit. I’d better put in a note that makes it sound like Puccini.” He found his inspiration to write dried up. Only in the past few years has he returned to the spontaneity in writing that he knew before his training in composition.

Although several of the composers hated the strict regimen imposed on them by their composition teachers, some indicated that they needed the rigorous background provided by disciplined study. The teachers who got the highest ratings were those who put the composers on their own and helped them develop their own style through relating to their ideas. One composer indicated that his best “teacher” has been an extensive library of orchestral scores.

The Process of Musical Composition

The composers included in this study seem to proceed through somewhat similar steps in creating music. The stages in musical composition upon which the most agreement was found are represented in Figure 1. The initial phase involves the crucial step of getting what may be called the germinal idea, variously termed the “germ,” the “kernel,” the “inspiration,” or the “idea.” The germinal idea may take a variety of forms – a melodic theme, a rhythm, a chord progression, a texture, a “kind of sound,” or a total picture of the work. The germinal idea associated with the first composition seems to be related to learning to play some musical instrument. Along with this internalized “cognitive map” of some musical instrument, many composers develop or are born with rich tonal fantasy.6

Once the germinal idea has been found, the composer may simply let it run around in his head for awhile. Sometimes the germinal idea is played over and over on some musical instrument, but more frequently it is written down. At this time, distractions and interruptions can easily obliterate the germinal idea, probably because of retroactive inhibition, that is, difficulty in recall due to some event occurring between the formation of the memory trace and attempted recall following an intervening activity. Transforming the germinal idea into a visual form therefore helps preserve the germinal idea for later use.

If the germinal idea is a really potent one, the author has found that it is seldom forgotten. Graf or the psychoanalytically oriented might attribute this to unconscious or preconscious mental processes,7 but there may be another way to explain it. Kleinsmith and Kaplan found in a one-trial learning situation that items that elicited high arousal were actually recalled less well than items eliciting a low level of excitement when retention was measured immediately after presentation.8 However, on a long-term retention test, the items that elicited high arousal were clearly better remembered than items evoking low arousal. Low arousal items exhibited the typical forgetting curve. This original research has now been replicated by others.9 The explanation for this effect has been that consolidation of the memory trace in long-term memory is somehow facilitated by emotional components, although the value of the higher arousal does not become obvious unless long-term retention is measured. Could a similar process be involved in memory for germinal ideas in music?

The sketch of the germinal idea may be put away for periods ranging from a few minutes to several years. Not infrequently, the sketch leads directly into the next stage, referred to here as the first draft. Note in Figure 1 that a line has been drawn from the first draft back to the germinal idea and from the sketch back to the germinal idea. This is an attempt to portray the way in which first drafts and sketches can frequently lead to more new germinal ideas via a series of free-associations. Although composers in this study tend to work for two or three hours on the first draft, some work for longer periods. It is not uncommon for a composition to be written in chunks of 50, 100, or even 300 bars or more at a time. Contrary to what people often assume, frequently this is not done at the piano. As one composer said, “The piano is too limiting.” Once this first draft is completed, it is sometimes laid aside for a time. Returning to the first draft after being away from it for awhile is often used as a way of evaluating its worth. In the process of writing the first draft, it is not uncommon for the composer to run into snags – impasses where further progress seems impossible. Frequently, a night’s sleep or a brief walk will take care of the problem. These solutions to the problem of blockage in musical composition sound suspiciously like the release of what learning/memory theorists have called proactive inhibition (that is, interference with present recall resulting from the buildup of previous learning and memory).

The next stage in musical composition is referred to as elaboration and refinement (see Figure 1). Here the first draft is reworked and added to where appropriate. The compositional process usually concludes with the completion of the final draft and copying of the score. Score copying is a necessary evil that composers can do when unable to devote full attention to the composing process.

Following performance of the work, revisions are sometimes made. However, there appears to be some resistance to making major changes once the work is completed. As one composer said, the composition is a personal record of musical development at a particular point in time and it should stay basically that way. When asked whether composing is primarily a spontaneous or a logical process for them, these composers indicated that it is both. Getting the germinal idea seemed to involve more spontaneous processes, whereas the first draft, elaboration and refinement, and revision of the manuscript were more significantly influenced by logico-deductive processes.

The stages in musical composition described here may or may not be the proper categories for conceptualizing musical creation. The components included simply represent an attempt to describe the process, given the author’s interpretation of the data collected in this study.

The Germinal Idea Revisited

Volumes could be written about the various stages in writing music, but since the germinal idea is so central to the composing process, it seems crucial to understand its origin. One distinction that might be helpful in understanding the genesis of the germinal idea is the role of external vs. internal events. Two examples of internal events come to mind: (a) some emotional state, such as sexual arousal or sorrow; and (b) the monitoring of internal “happenings” during a trance or altered state of consciousness. Three examples of composing occurring in association with external events are: (1) some environmental occurrence such as talking, a climatic change, or taking a shower; (2) another work of art; and (3) improvising on some musical instrument, frequently the piano. The role of emotion in composing has been discussed by Bernstein.10 The general public, he notes, assumes that composers write while in a fit of rage, or passion, or ecstasy. Bernstein states: “Can you imagine me, as a composer, in a desperate mood, in a suicidal mood, ready to give everything up, sitting down at the piano and writing the ‘Pathetique’ Symphony by Tchaikovsky? How could I? I’d be in no condition to write my name.”11

In the present study, composers were asked if any particular emotional state stimulates their composing. The answer in six out of eight cases fell along the dimension of tranquility-security-relaxation. Two composers indicated that sexual arousal plays a role in their composing. A much more common response was that when a piece of music was written depicting sadness, anger, or some other emotion, it was composed long after the emotional state had vanished. This corroborates what Hindemith has said on the subject, namely that composers apparently compose music representing their memories of images and feelings – not the feelings and images per se.12

Perhaps in discussing the role of emotion in musical composition it would be helpful to distinguish between the six stages of musical composition identified in this paper. A high level of emotional arousal could be utterly disruptive during creation of the first draft, elaboration and refinement, final draft, and revision of the composition. An elevated emotional state may present fewer problems during the germinal idea and sketching stages. Certainly this could be determined empirically. Secondly, there may be optimal levels of emotional arousal that facilitate musical composition. One would expect many individual differences in this regard.

Internal events associated with semitrance states or altered states of consciousness are strongly implicated by Bernstein.13 He notes that he sometimes composes at the piano, and sometimes at a desk, and sometimes in airports, and sometimes walking along the street, but mostly he composes lying down on a sofa or bed. Having assumed the prone position, he attempts to put himself into a trance-like state, which is “… not very far from being out of my mind.” 14 Bernstein observes that:

… all composers pray for some kind of instrument to be invented that can be attached to your head, as you are lying there in this trance, that will record all the nonsense going on, so that you don’t have to keep this kind of “watchdog,” schizophrenic thing going on: where by half of you is allowed to do what it wants, and the other half has to be at attention to watch what the first half is doing. You can wind up screaming in a schizophrenic ward eventually. Maybe that has something to do with the closeness between insanity and talent.15

But the outcome for Bernstein is obviously worthwhile:

… I wish I could convey to you the excitement and insane joy of it, which nothing else touches – not making love, not that wonderful glass of orange juice in the morning; nothing! Nothing touches the extraordinary jubilant sensation of being caught up in this thing – that you’re not just inside yourself, not just lying there. Let’s say that you get an idea and you go to the piano and you start with it; and you don’t know what you’re going to do next, and then you’re doing something else next, and you can’t stop doing the next thing, and you don’t know why. It’s madness and it’s marvelous. There’s nothing in the world like it.16

Several comments by composers in this study seemed consistent with the state of mind that Bernstein appears to be talking about. For one thing, in discussing environmental requirements for composing, five of the eight participants said they must be alone; two people stressed the importance of silence. Four emphasized that they must be free from disruptions, distractions, and problems to solve (e.g. the phone ringing, people talking). Three other people mentioned that they must have lots of leisure time, even more time than they know what to do with (time to “daydream?”). Two composers remarked that some of their ideas occur while driving along the Washington, D. C., Beltway; on these occasions they sometimes find themselves on the other side of town without the vaguest notion of how they got there. One participant in the present study indicated that his ideas frequently occur just before going to sleep or just after waking. A composer in this study once had the experience of dreaming about a melody while asleep, waking up, and being able to write it down (this has also happened to the author). This is the way one composer described how he gets the germinal idea:

It’s like a lightning flash that you have to grab …. It has to come from the depths and you have to be listening. You have to meditate. You have to shutout what’s around you or just be very aware of yourself.17

The foregoing findings suggest that the occurrence of germinal ideas may in many instances be related to the attainment of an altered state of consciousness. Yet there may be external events that are associated with the occurrence of germinal ideas with or without altered states of consciousness. Graf reports that Mahler’s song Tambourgesell was born in the instant when the composer left the dining room.18 Mozart wrote his Kegelstatt-Trio while playing nine-pins.19 Schindler (reported in Graf) noted that Beethoven was sometimes surprised by musical ideas “while in the midst of gay company, or sometimes in the street.” 20 One cannot rule out the possible role of altered states of consciousness in these instances, but neither should we exclude the possibility of external stimuli contributing to the occurrence of germinal ideas.

Writing of music in response to some other work of art is another instance in which the environment influences musical composition. There are a multitude of examples of this in musical history, including the familiar story of how Mussorgsky wrote Pictures at an Exhibition after viewing a group of Hartmann’s paintings. In a more empirical vein, Willmann studied musical compositions stimulated by four geometric designs.21 He found that there was a carry-over from the abstract designs to the musical themes written by the composers, suggesting that musical compositions can be influenced by an abstract design when used as a stimulus for creative work.

One composer in the present study had just received a poem that he thought would lead to a composition. Another participant had recently received a commission from the National Symphony to write a major symphony. He described the origin of the germinal idea for this work, which was stimulated by a passage from one of Mark Twain’s books:

There’s this Mark Twain thing I’m doing. I’ve written absolutely not one note of it – but as for the ice storm, I’ve set in my mind, “When the leafless tree is clothed with ice from the bottom to the top, ice that is as bright and clear as crystal… (singing).” Now I haven’t written it down, but I’ve had it in my mind for several weeks and I know that that will be the germ from which the movement will evolve…. It’s determined in this case by the words, “The ice is clear and ….” 22

Improvisation is another external variable that may play a role in generating the germinal idea. Improvisation involves explorations on a musical instrument such as the piano. These explorations sometimes result in lucky musical accidents. The true creator, Stravinsky believes, grasps these accidents and develops them into something substantive.23 Many well-known composers (Haydn, for example) have used improvisation as a means for generating germinal ideas, though the composers in the present study did not report using it frequently.

Some Unanswered Questions

The present study suggests the need for more research in the process of musical creation. One topic requiring further study is the average age when the first composition occurs. From the data collected in this study, it would appear that the first composition can occur over a broad age range. We need to know considerably more about the emotional, cognitive, and environmental factors that are associated with the occurrence of the first musical composition.

The adequacy of training in composition is another important area requiring further research. How happy are composers as a group with the compositional training they have received? What experiences facilitated development in musical creativity? What was inadequate or inappropriate about the compositional training received by composers?

More research is also needed on the stages involved in musical composition. Are the stages identified in this study an accurate portrayal of the process of musical creation? If not, what modifications are warranted? Is Graf’s psychoanalytic approach to musical creation more or less appropriate than explanations based on theories of learning and memory?

The role of emotion in musical creation remains to be fully explored. Is emotional arousal a distractor or facilitator of compositional activity? Does emotionality produce equivalent effects across all six stages in musical composition? Can the probability of recalling the germinal idea be predicted on the basis of arousal level occurring at the time of musical invention?

Another topic requiring study is the role of altered states of consciousness during musical composition. This could be evaluated by monitoring brain wave activity during musical composition (though the required electroencephalographic equipment would need to be made relatively unobtrusive). If altered states of consciousness are involved in musical creation, it is important to determine whether composers could become more proficient in composition by learning to control brain wave activity.

In order to remove some of the mysterious aura surrounding the act of musical creation, it is imperative that we understand more about the conditions influencing musical invention. If these contributing factors are better understood, and this information is used to generate new approaches to training in musical composition,24 perhaps more people will attempt to express their thoughts and feelings through the medium of music.

Institute for Child Study

University of Maryland

CollegePark

EndNotes

1 L. Sabaneev, “The Psychology of the Musico-Creative Process,” Psyche, Vol. 9 (July 1928), pp. 37-54.

2 J. Bahle, “Die Gestaltiibertragung im vokalen Schaffen Zeitgenössischer Komponisten (Gestalt as Applied to Vocal Compositions of Contemporary Composers),” Archiv für die Gesamte Psychologie, Vol. 91 (August 1934), pp. 444-451. J. Bahle, “Zur Psychologie des Einfalls und der Inspiration im musikalischen Schaffen” (The Psychology of Association and Inspiration in Creative Work in Music), Acta Psychologica, Vol. 1 (Hague: 1935), pp. 7-29. J. Bahle, Der musikalische Schaffensprozess. Psychologie der srhbpferischen Erlebnisund Antriebsformen (The Process of Musical Composition: The Psychology of Its Creative Forms of Experiences and Urges) (Leipzig: Hirzel, 1936). J. Bahle, “Arbeitstvpus und Inspirationstypus im Schaffen der Komponisten (The Work-type and the Inspiration Type Among Composers),” Zeitschrift für Psychologie, Vol. 142 (February 1938), pp. 313-322. J. Bahle, Eingebung und Tat im musikalischen Schaffen (Inspiration and Action in Musical Creation) (Leipzig: Hirzel, 1939).

3 Bahle, Eingebung und Tat im musikalischen Schaffen.

4 Max Graf, From Beethoven to Shostakovich: The Psychology of the Composing Process (New York: Philosophical Library, 1947).

5 Two composers contacted refused to participate in the study-one man and one woman. For some speculations about the paucity of women composers see Dennison J. Nash, “The Socialization of an Artist: The American Composer,” Social Forces, Vol. 35 (May 1957), pp. 307-313.

6 E. P. Torrance, “Originality of Imagery in Identifying Creative Talent in Music,” Gifted Child Quarterly, Vol. 13 (Spring 1969), pp. 3-8.

7 Graf, pp. 77-154.

8 L. J. Kleinsmith and S. Kaplan, “Paired-associate Learning as a Function of Arousal and Interpolated Interval,” Journal of Experimental Psychology, Vol. 65 (February 1963), pp. 190-193. L. J. Kleinsmith and S. Kaplan, “Interaction of Arousal and Recall Interval in Nonsense Syllable Paired-associate Learning,” Journal of Experimental Psychology, Vol. 67 (February 1964), pp. 124-126.

9 D. E. Batten, “Recall of Paired Associates as a Function of Arousal and Recall Interval,” Perceptual and Motor Skills, Vol. 24 (June 1967), pp. 1055-1058. M. Johnna Butter, “Differential Recall of Paired Associates as a Function of Arousal and Concreteness-Imagery Levels,” Journal of Experimental Psychology, Vol. 84 (May 1970), pp. 252-256. E. Levonian, “Retention of Information in Relation to Arousal During Continuously-Presented Material,” American Educational Research Journal, Vol. 4 (March 1967), pp. 103-116. P. D. McLean, “Induced Arousal and Time of Recall as Determinants of Paired Associate Recall,” British Journal of Psychology, Vol. 60 (February 1969), pp. 57-62.

10 Leonard Bernstein, The Infinite Variety of Music (New York: New American Library, 1970), pp. 273-275.

11 Bernstein, pp. 274-275.

12 Paul Hindemith, A Composer’s World (Garden City, N. Y.: Anchor Books, 1961), pp. 41-51.

13 Bernstein, pp. 269-271.

14 Bernstein, p. 269.

15 Bernstein, p. 271.

16 Bernstein, p. 283.

17 Thomas Beveridge, personal interview, July 1973.

18 Graf, p. 275.

19 Graf, p. 275.

20 Graf, p. 275.

21 R. R. Willmann, “An Experimental Investigation of the Creative Process in Music,” Psychological Monographs, Vol. 47 (1944), No. 1, pp. 1-76.

22 Robert Evett, personal interview, July 1973.

23 Igor Stravinsky, Poetics of Music (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1947).

24 Stan Bennett, “Learning to Compose: Some Research, Some Suggestions,” Journal of Creative Behavior, Vol. 9 No. 3 (Third Quarter 1975), pp. 205-210.

Interactive 3.1

Feedback/Errata