Main Body

2 Defining My Personal Values

Donnette Noble & Jeni McRay

INTRODUCTION

What beliefs are important to you? What are the values that help to define who you are and impact what you think, how you act, and how you feel? These are questions that may seem simple to answer, but further study reveals that our values are driving factors in how we choose to live, learn, and lead. This chapter will examine what values are, how they develop, how they are used in decision-making, and how they impact our relationships, vocation, and other parts of our life.

CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to…

- define what values are and how they are formed.

- identify your current personal values.

- distinguish some of the cultural and/or social considerations that impact your values.

- understand how to leverage your values to drive positive change.

KEYWORDS: Beliefs, ideals, ethics, morals, alignment, values

Our values guide, motivate, and influence our attitudes and behaviors (Boer & Fischer, 2013). Values encompass our beliefs and ideals, and those are based on the things we learn from others – parents, peers, schools, faith-based communities, government, media, etc. (Fritz et al., 2005). Beliefs (Merriam-Webster, n.d.) are a state of mind or habits wherein trust or confidence is placed in a person or a thing; they are things that are accepted and considered to be true. Ideals (Merriam-Webster, n.d.) are standards or expectations of goals to achieve or models to emulate. Just like values, beliefs, and ideals will differ among people. See Figure 1 for examples of values.

Figure 1 | Values Word Cloud

Quite simply, values are individually internalized attitudes about what is right, wrong, ethical, unethical, moral, and immoral. Values can influence our perceptions of problems, our preferences, and the choices we make related to our behavior. Examples of values include fairness, justice, honesty, freedom, equality, altruism, loyalty, and civility (Yukl, 2013). Values exist at the individual level, societal or communal level, national level, and within all types of organizations.

Values are not necessarily static, however, and can fluctuate over time when new information is made available, a new experience unfolds, or some new understanding reveals itself. Value systems will also vary, sometimes quite dramatically, from culture to culture and even among the various subcultures within a given country or region.

Our values frame how we view the world around us. This chapter addresses the individual beliefs that serve to motivate people to think and behave in certain ways. It also examines what influences people, shapes their values, and considers the conundrum of competing values as well as how and why values might shift over time. Furthermore, this chapter will present a clear distinction between ethics (studying the societal standards of right and wrong, a legal and codified set of agreed-upon behaviors) and morals (individual principles related to right and wrong). There should be congruence among our values, decision-making, approaches to leadership, and intentions. This chapter also shines a “spotlight” on a convicted felon who thought he held strong and ethical values, yet he participated in one of the biggest corporate fraud cases in United States (U.S.) history.

CHAPTER SPOTLIGHT

In 2000, Andrew Fastow, the former Chief Financial Officer (CFO) for Enron, was named CFO of the Year by CFO Magazine, but “This is my actual trophy,” he later told the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners (ACFE) as he held up his prison ID card (Coonan, 2016). “Every inmate in the federal system is supposed to carry this at all times,” explained Fastow (Coonan, 2016, para. 4). Here’s the interesting thing—he received both the award and the prison card in the same year. How do you become CFO of the Year at the same time that you are committing one of the biggest frauds in the history of corporate America?

In 1985, after the Federal Government deregulated natural gas pipelines, two companies (Houston Natural Gas and InterNorth) merged to form Enron. During the merger process, Enron incurred massive debt, but because of the deregulation of the industry, the company did not have exclusive rights to pipelines. This caused some problems for the company. For Enron to survive, it had to come up with a new and innovative strategy to generate profits and ensure a steady cash flow (Thomas, 2002). The Chief Executive Officer (CEO) hired a global management firm to develop a new strategy. The firm assigned Jeffrey Skilling, an experienced consultant, to take the lead in designing a revolutionary solution. Skilling quickly rose through Enron’s corporate ranks, and ultimately tapped Fastow to be a part of the team.

It was Fastow who was the real “mastermind behind a supremely complex network of off-balance-sheet special purpose entities and shell companies [that were] used to conceal years of massive losses [that were] leveraged on Enron stock” (Coonan, 2016, para. 6). Fastow was a genius in finding business management workarounds and tax loopholes, and all of the maneuvering he choreographed “was approved by the accountants at Enron, the outside auditors, the internal attorneys, the outside attorneys and the board of directors” (Coonan, 2016, para. 8).

Throughout the spring and summer of 2001, the risky deals Enron had made in terms of its underperforming investments began to unravel and caused the company to suffer a huge cash shortfall (Thomas, 2002) that ultimately led to its spectacular collapse when $1 billion in employee retirement funds and 5,000 jobs were wiped out overnight (Flanagan, 2020).

Prior to the collapse, Fastow considered himself to be a hero of sorts (Flanagan, 2020), but, in the end, he served six years in prison for his part in the fraud (a reduced sentence for providing evidence against his colleagues). Skilling (the CEO) served 12 years, and the Chairman of the Board (Ken Lay) died while awaiting his sentencing. Fastow, with the tacit approval of others, followed the rules but compromised values and hurt a lot of people in the process.

“For many organizations, values are a social glue” (Manning & Curtis, 2009, p. 105). Values are used to create a sense of corporate identity, and they can foster greater cohesion. They can also be relied upon to increase effective decision-making: “To be meaningful, values must enter into the daily practice of the organization [and] reflect enduring commitments, not vague and empty platitudes” (p. 105). When it came to Enron, the company’s core values of communication, respect, integrity, and excellence (Enron, 2000) were shrouded in hypocrisy.

As you reflect on this case study, can you think of other situations where people “followed the rules but compromised values”? Can you think of a situation where you have “followed the rules” but still compromised your own values?

History

“For millennia, philosophers, sociologists, psychologists, and others have tried to figure out just exactly what values are” (Sharma, 2015, p. 42). The word, values, comes from the Latin “valeo” which means to be strong (Sharma, 2015). According to Halstead and Taylor (2000), values can be broadly defined as the principles or fundamental convictions which serve as general guides to human behavior and the related actions are then judged as good or desirable (or not). They can also be considered “abstract ideals” as they relate to people’s behavior (Hanel et al., 2018, p. 1).

In the 1930s, a psychologist, Gordon Allport (1937), created a list of values, or what he thought were easily recognized consistencies, that tend to define and support a person’s unique path in life (Sharma, 2015). The first of Allport’s values or consistencies is theoretical and encompasses the pursuit of truth and objectivity (something we’ve heard a lot about in the last couple of years but more about that later in the chapter). The second one, economic, is all about usefulness and practicality. The third is aesthetic, which focuses on harmony and beauty. The next is social, which is centered on love and compassion for people. Then there is political value which hinges on power, and finally, religious value which is defined by unity or moral excellence (Tsirogianni & Gaskell, 2011).

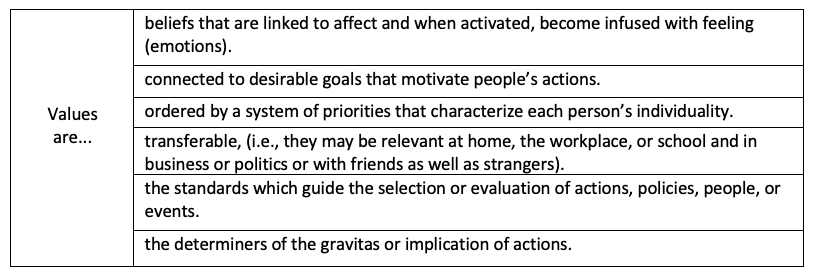

Each person is in possession of any number of values, and those values are tied to varying degrees of importance (Schwartz, 2012). For example, a value that may be critically important to one person may not be at all important to someone else. Relying on the works of many theorists over the years (Allport, 1961; Feather, 1995; Kluckhohn, 1951; Morris, 1956; & Rokeach, 1973), Schwartz (2012) contends there are six main features to values (pp. 3-4); (see Table 1).

Table 1 | What are Values?

Defining Values

Social values are the standards that influence the judgments we have about ourselves and others, and they impress upon us what is important as we pursue our individual purpose in life; thus, they are also closely tied to our self-conception. As we endeavor to make value-enhancing choices across the different domains of our lives, we find that our values contribute to our sense of self-worth and efficacy (Tsirogianni & Gaskell, 2011). Values are used to characterize cultural groups, societies, and individuals. Additionally, they are used to trace personal changes over time and can explain the motivational bases of attitudes and behaviors (Schwartz, 2012).

The early years of a child’s life are often completely dependent on their parents: “Parents are a child’s first and most significant shapers of character” (MacElroy, 2003, para. 3). As we grow older, we develop our morals and values, not only based on parental influence but also on the influence from peers. As young people leave home and transition to college, more people come into their lives who play a part in shaping their sense of self (MacElroy, 2003). These new relationships, increased freedom, and more latitude in decision-making can result in shifts or challenges to previously held values.

Values have contextual relevance, and some may cross into different domains while others may not. Personal values related to self may include education, academic accomplishments, physical fitness, self-respect and esteem, responsibility, creativity, wealth, social status, or humor. Relationship values are comprised of concepts such as family, friends, love, loyalty, camaraderie, harmony, and diversity of perspectives. Justice, recognition, opportunities, expertise, and goal achievement are considered vocational values. Spiritual values may address forgiveness, reflection, integrity, wisdom, inner peace, and optimism.

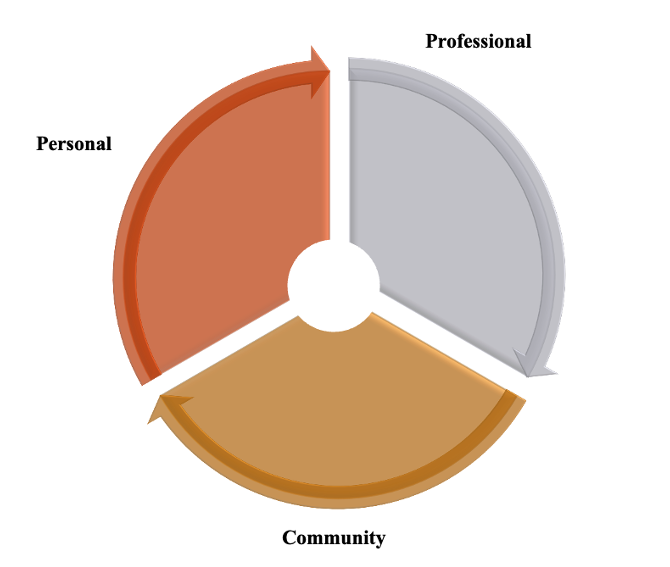

One mechanism to help students assess their own values is adapted from the BCJ Institute for Learning and Development (See Figure 2).

Figure 2 | Values Wheel

When people take time to examine their values and think about what is important to them and why, they are more prepared to meet life’s challenges. Having a strong sense of values helps to create a road map that helps them to figure out things such as (BCJ, nd):

- What are their goals and how will they get there?

- What should be prioritized in life?

- How do they want to behave in certain situations?

- What is the best course of action when making decisions?

- What would they like their legacy to be?

There are, however, situations when people find themselves not living in accordance with their values, and this misalignment can create stress, anger, or anxiety and conjure up other negative emotions. Additionally, a lack of alignment can lead to poor or even unethical decision-making. This is why consistency among our values, thoughts, and actions is so critically important. Additionally, when we are living in alignment with our values, we are more resilient and better equipped to address difficulties that will inevitably arise over time.

ACTIVITIES

Values Assessment

Begin this activity by dividing a piece of paper into three columns and label the columns, Personal, Professional, and Community. Under each of the three headings, make a list of values that are important to you personally, professionally, and in terms of community. For example, when it comes to personal values, love and kindness may be important to you. Professionally you might value transparency or integrity. When it comes to community you may value justice or safety. If you need help getting started, click this link for a list of 305 values.

Once you have developed a meaningful list of values, go back through the list and place a star by the five most important values in each of the three categories. For the purpose of this exercise, we will refer to these as your core values.

Next, prioritize each of your five core values from each section and plot them by drawing the diagram from Figure 2 on a sheet of paper and placing the values in the appropriate category. The most important of the five core values from each list will be closest to the center of the diagram, whereas the values with lesser priority will be toward the periphery of the diagram in each section. Now you have the start of a personalized road map that will aid in helping you maintain consistency in your values, thoughts, and actions in three distinct spaces of your life – personal, professional, and community.

Be ready to discuss your values in each category with the class.

As you think about the motivational bases of attitudes and behaviors, consider what has happened since January 2020. The world has collectively lived with the COVID-19 pandemic, an experience that forced people to reevaluate what is important to them. People have had to reassess what they value and how those values affect their decisions in terms of living through unprecedented circumstances. The U.S. comprises less than 5% of the global population

(Whelan, 2020), yet leads the world in the total number of reported COVID cases (77,956,627) as well as reported deaths (923,110) as of February 15, 2022 (John Hopkins, 2021). These figures have required that people reflect on the role of science in their lives, in addition to considering how mask mandates, social restrictions, and the availability of COVID vaccines impact their values, if at all. This raises one conundrum after another for thoughtful individuals who are trying to sift through the noise to find answers. For instance, do personal liberty and freedom (individual values) take precedence over the greater good of public health concerns (collective values)? The answers lie within the beliefs, ideals, and values each person holds.

Leadership, Values, and Change

There are many facets to power, and it can be exerted for good or ill. A leader’s personal values and internal code of ethics may be among the most important determinants in terms of how a leader will exercise power (Hughes et al., 2015). Leaders will undoubtedly be faced with challenges time and again, and those challenges often lack simplistic answers. The key is doing what is right and not just what is expedient. This is where authentic leadership comes into play: “authentic leaders exhibit consistency among their values, their beliefs, and their actions” (p. 166), and “honesty, altruism, kindness, fairness, accountability, and optimism” have been identified as core values of authentic leaders (Yukl, 2013, p. 351). The tenets of altruism, fairness, and accountability can be significant drivers of social change.

The basic values we hold dear are those that help us set our course for action as responsible individuals and community members who are concerned with protecting our democratic society. Indeed, the Social Change Model (HERI, 1996) hinges entirely on values with an expectation that leadership will be inclusive. Leadership is a process and not a position, and it explicitly promotes additional values of equity, social justice, self-knowledge, personal empowerment, collaboration, citizenship, and service (Noble & Kniffin, 2021).

The year 2020 was rife with racial and social tensions in the United States. The calls for social justice were amplified after George Floyd was killed by a police officer in Minneapolis:

Floyd’s death sent a nation of people in quarantine out into the streets in mass protests. Major corporations issued statements in support of Black Lives Matter. Politicians promised a new direction. Years later, some activists argue there is still more work to be done to reach equity and social justice for Black and brown people (Gunderson, 2021, para. 2 – 3).

The Black Lives Matter movement is demonstrative of how racial and social tensions have the power to divide a society based on differing values systems. There is a delicate balancing act that must take place between individual values and those that are important to others. To bridge the gap that these differences create, we must use empathy to better understand the values behind differing opinions. By taking time to understand the values of others, we can identify ways to better engage with others.

Value Systems, Alignment, and Change

One of the national values of the U.S. is explicitly stated in what was considered its defacto motto until 1956, E Pluribus Unum, meaning “from the many, one” (B., 2011). It is a testament to the fact that, from its beginning, the U.S. has been a pluralistic society where different races, ethnicities, religions, traditions, and languages have converged to co-create and share a common national experience; however, the persistence of deep differences among the people residing in the United States raises the corollary challenge of how to maintain at least a basic level of social cohesion and solidarity when in fact, those “deep differences” (Hoover, 2016, p. 26) very often result in competing value systems. While some differences are accommodated, “Peaceful, constructive pluralism doesn’t “just happen.” It requires leadership, both from the top-down (government) and the bottom-up (civil society). Social flourishing becomes sustainable, even under conditions of deepening diversity, when all stakeholders develop reserves of commitment…” (Hoover, 2016, p. 27) to supporting one another and honoring the differences among us – including the ebb and flow of our fluctuating values.

Adding layers to the complexity of competing values are disparate views of both morals and ethics. While the terms are often interchanged, they are not necessarily the same thing. Both words refer to some form of proper conduct (Rosenstand, 1997). Morals address customs or habits, whereas ethics (or moral philosophy) is the study of moral judgments about what is virtuous (or not), just or unjust, right or wrong, good or bad or evil (Moore & Bruder, 2008).

While personality traits are relatively stable throughout one’s life, values are characteristic adaptations and motivational goals that can change as a function of developmental priorities at different ages and stages of one’s life (Gouveia et al., 2015). Schwartz (2012) proffers that there are three systematic sources of age-related differences that can result in shifts in values. These shifts can occur in response to a person’s changing roles associated with their stage in life (this is the first of the systematic sources of changing values). Some of the values of a young, relatively unencumbered, traditional-aged college student likely differ rather significantly when compared to those of a mid-career professional with a partner or spouse and children to raise. The second systematic source of shifts in values is the result of physiological or biological changes – changes in maturity and/or abilities which could include declines in energy and sharpness of the senses. Finally, changes in values can result from societal changes, including democratization and political and economic stability (Gouveia et al., 2015).

Summary

Broadly speaking, Brown (2012) suggests there are two buckets that people will put their values into – the practiced values bucket (what we are actually doing, thinking, and feeling) and the aspirational values bucket (what we want to do, think, and feel). The difference between what is practiced and what is aspirational results in a values gap. Brown (2012) contends that disengagement is inevitable when practiced values conflict with aspirational values and expectations within a culture. Disengagement (detaching, releasing, disconnecting, or withdrawing from someone or something) is the issue underlying the majority of problems that exist in families, schools, communities, and organizations. We must, therefore, mind the gap and stay focused to ensure that our values are aligned and match our actions (Brown, 2012).

Values are messy and complex: “Thinking about [them] is not a luxury; you live them every day of your life. Your values show in the way you treat your friends, enemies, [and others], and they determine your politics, ethics, emotions, daydreams, life, and leisure” (Halberstam, 1993, p.

186). The way we engage our values and how they drive our lives is a lifelong process. What kind of a leader you are will be reflected in how you handle the challenges surrounding your beliefs, ideals, and values – particularly when they collide.

QUESTIONS FOR JOURNALING OR DISCUSSION

- If you are involved in or have completed a service-learning project this semester, identify some of the organizational values you observed. If you haven’t participated in a service-learning project before, identify some of the values you’ve observed in an organization that you have been a client or customer of (either non-profit or for-profit).

- Think about some of the groups you interact with (at home, at school, at work, etc.) and identify some of the values you observed.

- How do the values you observed in the situations described above align with your own values (if they do)?

- If the values you observed are different from your own, what things do you think contributed to those differences?

- When you think of social change, what issues are important to you and which of your values are congruent with those issues?

- Think about a time when you had to work through a difficult situation where two or more of your values were in conflict. How did that make you feel and how did you resolve the situation?

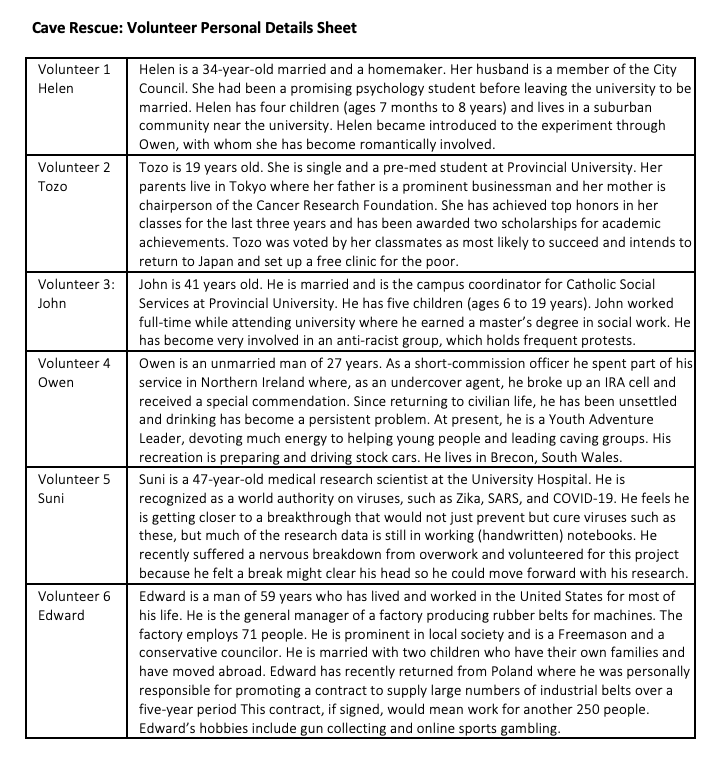

Cave Rescue

Read the following Scenario about a caving accident. After reading the scenario, carefully complete the steps that follow in order. Please do not skip any steps in this process.

Scenario

Your group is asked to take the role of a research management committee that is funding projects into human behavior in confined spaces. You have been called to an emergency meeting as one of the experiments has run into an emergency situation.

Six volunteers have been taken into a cave system in a remote part of the country connected only by a radio link to the research hut by the cave entrance. It was intended that the volunteers would spend four days underground, but they have been trapped by falling rocks and rising water.

The only rescue team available tells you that rescue will be extremely difficult, and only one person can be brought out each hour with the equipment at their disposal. It is likely that the rapidly rising water will drown some of the volunteers before rescue can be completed.

The volunteers are aware of the dangers of their plight. They have contacted the research hut using the radio link and said that they are unwilling to make a decision regarding the order in which they will be rescued. By the terms of the research project, the responsibility for making this decision now rests with your committee.

Life-saving equipment will arrive in 50 minutes at the cave entrance, and you will need to advise the team of the order for rescue by completing the ranking sheet provided below. The only information you have available is drawn from the project files and is reproduced on the volunteer personal details sheet that can be found below. You may use any criteria you think fit to help you make a decision.

Now that you have reviewed the Volunteer Personal Details Sheet, complete the following steps in order. Please do not skip any steps:

Now that you have reviewed the Volunteer Personal Details Sheet, complete the following steps in order. Please do not skip any steps:

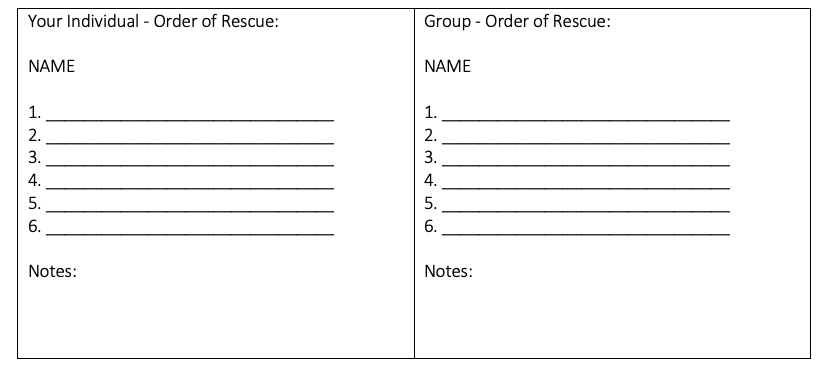

- Individually, use a ranking sheet (see sample below) to indicate the order the volunteers should be extracted from the cave. Write your answers in the left-hand column. You have 10 minutes to do this.

- Working in your groups, discuss the order in which each of you believes each of the volunteers should be removed from the cave. Work to arrive at a group decision by sharing your reasons or criteria and working to develop criteria the group can agree to. Use the right-hand column to record the group consensus.

- Collectively, use a group ranking sheet (see example below) to present the order of extraction from the cave. Share with the class the order of extraction your group arrived at and the issues and values that were discussed in arriving at your decisions.

Cave Rescue Ranking Sheet

Questions for Consideration:

- Did your group establish a decision-making criterion? If so, what was it?

- Was consensus reached? If not, what criteria did you use to make your decisions?

- Did everyone feel their point of view was heard and considered by all other team members? Why or why not?

- Was anyone unhappy with the outcome? Why?

- What could other team members have done to listen and support each other?

- What emotions or feelings did you have that affected your ability to make decisions in this activity? What would you have recommended to the research team if this were a real activity?

REFERENCES

Allport, G. W. (1937). Personality: A psychological interpretation. Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Allport, G. W. (1961). Pattern and growth in personality. Holt, Reinhart & Winston.

Berkeley Well-Being Institute. Printable List of Values. https://www.berkeleywellbeing.com/uploads/1/9/4/8/19481349/printable-list-of-values.pdf

B. J. (2011). Change the motto of the United States of America to “E Pluribus Unum.” We the People. https://petitions.obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/petition/change-motto-united-states-america-e-pluribus-unum/

BJC Institute for Learning and Development (n.d.). Clarifying your values. https://www.bjclearn.org/resiliency/PDFs/001103.pdf

Boer, D., & Fischer, R. (2013). How and when do personal value guide our attitudes and sociality? Explaining cross-cultural variability in attitude-value linkages. Psychological Bulletin, 139(5), 1113–1147. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031347

Brown, B. (2012). Daring greatly: How the courage to be vulnerable transforms the way we live, love, parent, and lead. Avery.

Coonan, C. (2016, January 6). Former Enron CFO Andrew Fastow: You can follow all the rules and still commit fraud. The Irish Times. https://www.irishtimes.com/business/companies/former-enron-cfo-andrew-fastow-you-%20can-follow-all-the-rules-and-still-commit-fraud-1.2485821

Enron. (2000). Enron annual report. https://picker.uchicago.edu/Enron/EnronAnnualReport2000.pdf

Feather, N. T. (1995). Values, valences, and choice: The influences of values on the perceived attractiveness and choice of alternatives. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68(6), 1135–1151. https://doi-org.libproxy.unl.edu/10.1037/0022-3514.68.6.1135

Flanagan, P. (2020, January 9). Enron’s former CFO Andrew Fastow once saw himself as ‘a hero.’ Chron. https://www.chron.com/business/energy/article/Andrew-Fastow-Who-Helped-Bring-Down-Enron-Saw-14962065.php

Fritz, S., Brown, W. F., Povlacs Lunde, J., & Banset, E. A. (2005). Interpersonal skills for leadership (2nd ed.). Pearson.

Gouveia, V. V., Vione, K., Milfont, T. L., & Fischer, R. (2015). Patterns of value change during the life span: Some evidence from a functional approach to values. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 4(9), 1276–1290. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167215594189

Gunderson, E. (2021). Social Justice Organizations Reflect on 2020 as Floyd Anniversary Nears. WTTW News. Retrieved January 15, 2023, from https://news.wttw.com/2021/05/23/social-justice-organizations-reflect-2020-floyd-anniversary-nears

Halberstam, J. (1993). Everyday ethics: Inspired solutions to real-life dilemmas. Viking/Penguin Books.

Halstead, J. M., & Taylor, M. J. (2000). Learning and teaching about values: A review of recent research. Cambridge Journal of Education, 30(2), 169–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/713657146

Hanel, P.H.P., Litzellachner, L .F., & Maio, G. R. (2018). An empirical comparison of human value models. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1643. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01643

Higher Education Research Institute. (1996). A Social Change Model of Leadership Development (Version III). UCLA. https://www.heri.ucla.edu/PDFs/pubs/ASocialChangeModelofLeadershipDevelopment.pdf

Hoover, D. R. (2016). Pluralist responses to pluralist realities in the United States. Society, 53(1), 20–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12115-015-9967-2

Hughes, R. L., Ginnett, R. C., & Curphy, G. J., (2015). Leadership: Enhancing the lessons of experience (8th ed.). McGraw Hill.

John Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. (2022). COVID-19 dashboard. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html

Kluckhohn, C. (1951). Values and value-orientations in the theory of action: An exploration in definition and classification. In G. W. Allport, C. Kluckhohn, H. A. Murray, R. R. Sears, R. C. Sheldon, S. A. Stouffer, & E. C. Tolman (Eds.), Toward a General Theory of Action (pp. 388–433). Harvard University Press. https://doi.org/10.4159/harvard.9780674863507.c8

MacElroy, M. (2003). Educating for character: Teaching values in the college environment. The Vermont Connection, 24(1). https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/tvc/vol24/iss1/3

Manning, G., & Curtis, K. (2009). The art of leadership (3rd ed.). McGraw Hill.

Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Belief. In Merriam-Webster.com dictionary. Retrieved June 20, 2023, from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/belief

Merriam-Webster. (n.d.). Ideal. In Merriam-Webster.com dictionary. Retrieved June 20, 2023, from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/ideal

Moore, B. N., & Bruder, K. (2008). Philosophy: The power of ideas (7th ed.). McGraw Hill.

Morris, C. (1956). Varieties of human value. University of Chicago Press.

Noble, D., & Kniffin, L. E. (2021). Building sustainable civic learning and democratic engagement goals for the future. New Directions for Higher Education, 2021(195–196), 171–179. https://doi.org/10.1002/he.20421

Rokeach, M. (1973). The nature of human values. Free Press.

Rosenstand, N. (1997). The moral of the story: An introduction to ethics (2nd ed.). Mayfield Publishing.

Schwartz, S.H. (2012) An overview of the Schwartz theory of basic values. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.9707/2307- 0919.1116

Sharma, K. (2015). A comparative study of aesthetic, economic, and political values of undergraduate students. The International Journal of Indian Psychology, 2(2), 42–55. https://doi.org/10.25215/0202.008

Thomas, C. W. (2002). The rise and fall of Enron: When a company looks too good to be true, it usually is. Journal of Accountancy. https://www.journalofaccountancy.com/issues/2002/apr/theriseandfallofenron.html

Tsirogianni, S., & Gaskell, G. (2011). The role of plurality and context in social values. Journal for the Theory of Social Behavior. 41(4), 441–465. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5914.2011.00470.x

Whelan, N. (2020). Countries by percentage of world population. World atlas. https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/countries-by-percentage-of-world-population.html

Yukl, G. (2013). Leadership in organizations (8th ed.). Pearson.