Main Body

1 How I See Myself

Self-Awareness

Lindsay Hastings

INTRODUCTION

The way we see ourselves is critical to our development as leaders. The more we know about ourselves, the more strategic we can pursue leadership roles that fit our talents and values. The more we understand ourselves, the more easily we can understand others. The more mindful we can be of our feelings and state of mind, the more intentionally positive our actions can be. In short, our self-awareness as leaders is foundational and serves as an essential starting block for leadership development.

CHAPTER SPOTLIGHT

How we see ourselves is influenced by the messages we receive from others. Consider an example – Let us imagine two students, Lila and Jonah. Lila is in a home where she is appreciated and accepted. Every time she gets an ‘A’ on a test, she posts it on the refrigerator. Cherished adults in her life come to activities like soccer games and point out what she did well. Her teachers compliment her intellect and tell her she should go to college someday. What kind of picture does Lila have of herself? Would we imagine that picture to be positive or negative? Do we think Lila will work hard and do well in school? Why or why not? Do we think Lila might attend college? Why or why not?

Let us imagine Jonah is in a home where he is unappreciated and, frankly, ignored. No one asks how he is doing in school. No one cares if he gets an ‘A’ on a test. Important adults in his life rarely come to activities like soccer games and, if they do, only point out his mistakes. His teachers barely know his name, and no one has suggested attending college. What kind of picture does Jonah have of himself? Would we imagine that picture to be positive or negative? Do we think Jonah will work hard and do well in school? Why or why not? Do we think Jonah will attend college? Why or why not?

What if Lila and Jonah have roughly the same intellectual and athletic abilities? What would be the difference between them? The way others saw them. Again, how we see ourselves can be influenced by the messages we receive from others. Some messages from others are important to hear and retain. For example, we should cherish the messages we receive from our difference makers when they point out our talents and strengths. There may be other hurtful messages from our past that we need to reject or that we need to learn from and move forward. Each of us has the potential to be a great leader, and there is no such thing as a perfect leader. There has yet to be a standard set of personality characteristics in the research on leadership traits that are always associated with effective leadership. What does this mean for us? Each of us has the power to leverage what we uniquely do well to be an effective leader. Each of us has the power of positive influence. However, it is incumbent upon us to study ourselves, be students of our unique attributes, learn constructively from past experiences, and consider how to make a positive difference.

CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

By the end of this chapter, we will be able to…

- Describe and distinguish between self-awareness, self-concept, and self-esteem

- Explain the importance of self-awareness to developing our leadership identity

- Identify turning points that have shaped our leadership identity

- Recognize the value in our unique leadership identity

- Articulate the utility of becoming self-aware

KEYWORDS: Self-awareness, self-concept, self-esteem, leadership identity

We may not realize it, but we have been painting the picture of ourselves since birth. The messages we have received from others influence the picture of ourselves. Charles Horton Cooley, a sociologist from the University of Michigan, created a “looking glass self” principle in 1902. A “looking glass” is the same as a mirror, and the “looking glass self” principle suggests that we have an imaginary mirror from the top of our heads to the tip of our toes. Others reflect how we behave towards them, arguing that it takes two people to see one person. The way we view ourselves and the messages we receive from others form our picture of ourselves.

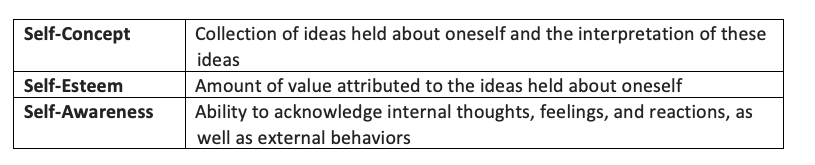

Self-Concept is the collection of ideas we hold about ourselves and how we interpret those ideas through our self-image or how we see ourselves. While self-concept is related to the ideas and interpretations we have of ourselves, self-esteem refers to how much value we place on ourselves (Rogers, 1959). In other words, self-esteem is determined by how much worth we attribute to those ideas we hold about ourselves. Positively seeing ourselves requires a commitment to self-awareness. Self-awareness is the ability to recognize our internal thoughts, feelings, and reactions, as well as our external behaviors (Fenigstein et al., 1975). Table 1 highlights the relationship between self-concept, self-esteem, and self-awareness.

Table 1 | Self-Concept, Self-Esteem, and Self-Awareness

Self-concept, self-esteem, and self-awareness all originate from psychology. However, the positive psychology movement has drawn attention to self-concept, self-esteem, and self-awareness, acknowledging that self-images impact our quality of life (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). Thus, remembering that the picture we have of ourselves is often influenced by the messages we receive from others, a consistent commitment to self-awareness affords us the opportunity to (a) see ourselves more positively when positive attributes are recognized, (b) reflect and grow in response to constructive criticism, and (c) reject destructive messages. In the Social Change Model (SCM), self-awareness is discussed explicitly through the value, Consciousness of Self.

Consciousness of Self is one of the individual values in the Social Change Model (SCM). It means “to know oneself, or simply to be self-aware” (HERI, 1996, p. 31). There are two aspects to Consciousness of Self: (a) personality (i.e., relatively stable aspects of ourselves like talents and values) and (b) mindfulness (i.e., ability to observe our behaviors, feelings, and state of mind). Consciousness of Self is critical to the SCM because other values like Collaboration and Controversy with Civility hinge on the development of self-awareness. For example, suppose we are self-aware of our talent for listening. We might use that talent to make sure all team members’ voices are heard during a team meeting. For example, self-awareness might also help us recognize aggravated feelings and create mental space to consider words and behaviors that maintain civility despite such feelings.

Consciousness of Self can benefit the self, groups, and communities. Groups form shared values and purposes when each group member has a strong awareness of their personal beliefs and values. Consciousness of Self is the key to unlocking the consciousness of others. The more we understand ourselves, the more we understand others.

Why does self-awareness matter to leadership?

Self-awareness matters to leadership because it helps formulate our identity as a leader. We might decide to pursue specific leadership roles on campus or in the community because we see a strong fit between our leadership talents and the demands of the leadership roles. Understanding our identity as leaders might help us determine where we can contribute best on a group project. Identity is central to our development as leaders because it helps us identify where and how to have the most positive influence.

Several respected leadership scholars have researched to document the relationship between identity and leadership for both adults (Day & Harrison, 2007; Day et al., 2008; Ibarra et al., 2014; Lord & Hall, 2005; Miscenko et al., 2017; Shaughnessy & Coats, 2019) as well as youth and college students (Day & Sin, 2011; Komives et al., 2005, 2006; Lord et al., 2011; Murphy, 2019; Murphy & Johnson, 2011). Specifically, leadership identity has been related to leadership effectiveness (Avolio & Hannah, 2008; Day & Sin, 2011). In other words, your self-awareness is linked to your effectiveness as a leader.

We might be asking, “So how do I develop my identity as a leader exactly?” The development of our identity as leaders will constantly be evolving. It may sometimes feel repetitive because we often will have to unpack previous experiences to help illuminate elements of our identity as leaders. Significant people, experiences, and our ability to reflect on those people and experiences will all influence our identity as leaders and our implicit views of leadership.

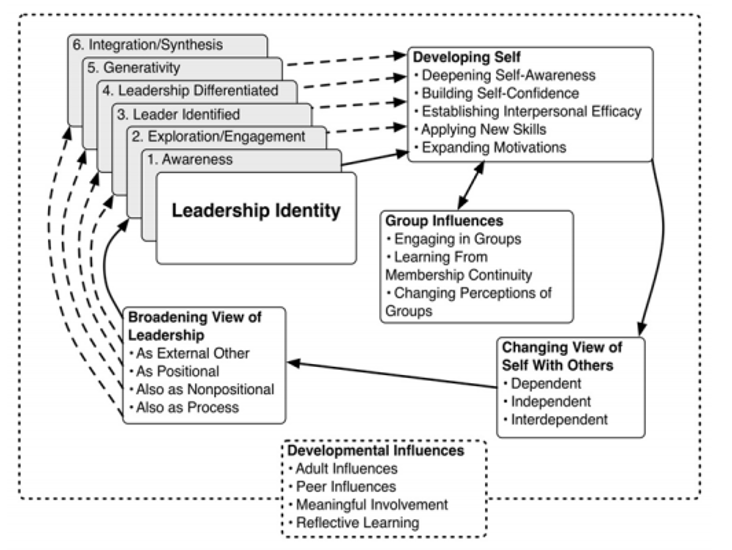

A group of scholars in the early 2000s conducted a foundational study to understand the development of leadership identity. Led by Dr. Susan Komives, this team of scholars conducted in-depth interviews with college students and formulated a six-stage process of leadership identity development (See Figure 1; Komives et al., 2005, 2006).

Figure 1 | Leadership Identity Development Model (Komives et al., 2006)

The first stage is Awareness, where we might recognize that leaders exist; however, we may not personally identify as a leader. The second stage is Exploration/Engagement, where we might intentionally get involved in groups and organizations and assume responsibility within those groups. Stage 3 is Leader Identified, where we start to see both leaders and followers in groups and identify leaders as those who hold a leadership position. We will know we are in Stage 4 (Leadership Differentiated) when we recognize that anyone in the group can do leadership. We start to see leadership as a process that requires lots of interdependence among the group members. The fifth stage (Generativity) will emerge when we take on a personal passion for our activities and actively commit to developing the leadership capacity of younger members. Finally, we will recognize that we have reached Stage 6 (Integration/Synthesis) when the word “leader” becomes integrated into our self-identity. We see leadership as not something we do but part of who we are. Leadership becomes part of our daily process. We apply our leadership in various situations (e.g., school, campus involvements, off-campus workplaces). We have a general sense of confidence in working effectively with people. The results from Komives et al.’s (2005, 2006) study demonstrated that the development of leadership identities constantly evolves and is influenced by adults, peers, meaningful involvement, and reflective learning (Priest et al., 2018).

While the Leadership Identity Development (LID) model helps us understand how our views of leadership might change and grow throughout our collegiate experience, our self-concept, self-esteem, and self-awareness contribute to formulating our unique leader identity. The activities at the end of this chapter help us (a) articulate our unique identity as a leader, (b) reflect on past experiences that have influenced our self-concept and self-esteem, (c) generate our definition of leadership, and (d) recognize our implicit views of leadership. Among the myriad definitions of leadership, the common denominator is the notion of influence. Each of us holds the power to leverage what we do uniquely well to influence our world positively.

QUESTIONS FOR JOURNALING OR DISCUSSION

-

- In what ways, if at all, do your self-concept and self-esteem support your development as a leader?

- How do your self-concept and self-esteem influence your behavior as a leader?

- In your opinion, how might low self-esteem due to a negative self-concept influence a leader’s effectiveness?

- What are ways to create regular opportunities to engage in self-awareness?

- How can a positive self-concept be maintained when experiencing negative messages from others?

ACTIVITY

Implicit Leadership

Identity Statements

Directions: Below is an incomplete sentence (I am…) intended to guide your thinking about your identity as a leader. For this activity, you are asked to write this prompt (incomplete sentence) ten times and fill in the blanks for each of the ten prompts. While it may be tempting to write things like, “I am __good at basketball___” or “I am___artistic___,” think about how you would describe yourself as a leader. What are your strengths as a leader? Where do you add value to a team? How are you, or how would you like to be a positive difference-maker?

Our life experiences shape how we see ourselves as leaders. Below each identity statement, reflect upon the significant moment(s) that shaped the identity statement and indicate why.

I am…________________________________________

- What significant moment has shaped this identity statement and why?

Reflection Prompts

Directions: Use these prompts to journal or reflect on your experiences related to self-esteem.

- What have been 3 – 5 “turning points” that have positively impacted your self-esteem?

- What have been 3 – 5 “turning points” that have negatively impacted your self-esteem?

- What have been the redemptive moments that have allowed you to overcome turning points that negatively impacted your self-esteem?

Definition of Leadership

Directions: Write your definition of leadership below. Use the prompts below to guide your thinking prior to writing your definition.

- Best leaders you have known

- Qualities that are associated with effective leadership:

- Worst leaders you have known

- Qualities that are associated with ineffective leadership

- Your definition of leadership

- Often, our current environment influences our definition of leadership. How has your current context influenced your definition?

Illustrations of Leadership

Directions: Pick an object from the pictures below and consider how that object illustrates your definition of leadership. With a partner, share your definition of leadership and indicate how your selected object illustrates your definition of leadership. Discuss the following questions together:

- What were the similarities in our leadership definitions?

- What were the differences in our leadership definitions?

- Why were there differences in our leadership definitions? How have our life experiences shaped our unique definitions of leadership?

(Implicit Leadership Activity; L. McElravy, personal communication, August, 30, 2021).

REFERENCES

Avolio, B. J., & Hannah, S. T. (2008). Developmental readiness: Accelerating leader development. Consulting Psychology Journal, 60, 331–347.

Cooley, C. H. (1902). Human Nature and the Social Order (New York: Scribner’s, 1902). Social Organization.

Day, D. V., & Harrison, M. M. (2007). A multilevel, identity-based approach to leadership development. Human Resource Management Review, 17(4), 360-373.

Day, D. V., Harrison, M. M., & Halpin, S. M. (2008). An integrative approach to leader development: Connecting adult development, identity, and expertise New York, NY: Taylor & Francis, LLC.

Day, D. V., & Sin, H. P. (2011). Longitudinal tests of an integrative model of leader development: Charting and understanding developmental trajectories. The Leadership Quarterly, 22(3), 545-560.

Fenigstein, A., Scheier, M. F., & Buss, A. H. (1975). Public and private self-consciousness: Assessment and theory. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 43(4), 522.

Higher Education Research Institute (HERI). (1996). A social change model of leadership development guidebook: Version III. Los Angeles, CA: Author.

Ibarra, H., Wittman, S., Petriglieri, G., & Day, D. V. (2014). Leadership and identity: An examination of three theories and new research directions. In D. V. Day (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of leadership and organizations (pp. 285 – 301). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Komives, S. R., Longerbeam, S. D., Owen, J. E., Mainella, F. C., & Osteen, L. (2006). A leadership identity model: Applications from a grounded theory. Journal of College Student Development, 47(4), 401 – 418.

Komives, S. R., Owen, J. E., Longerbeam, S. D., Mainella, F. C., & Osteen, L. (2005). Developing a leadership identity: A grounded theory. Journal of College Student Development, 46(6), 593 – 611.

Lord, R. G., & Hall, R. J. (2005). Identity, deep structure and the development of leadership skills. The Leadership Quarterly, 16(4), 591-615.

Lord, R. G., Hall, R. J., & Halpin, S. M. (2011). Leadership skill development and divergence: A model for the early effects of gender and race on leadership development. In S. E. Murphy & R. J. Reichard (Eds.), Early development and leadership (pp. 229-252). New York, NY: Routledge.

Miscenko, D., Guenter, H., & Day, D. V. (2017). Am I a leader? Examining leader identity development over time. The Leadership Quarterly, 28(5), 605–620. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2017.01.004

Murphy, S. E. (2019). Leadership development starts earlier than you think. In R. E. Riggio (Ed.), What’s wrong with leadership? Improving leadership research and practice (pp. 209 – 225). New York, NY: Routledge.

Murphy, S. E., & Johnson, S. K. (2011). The benefits of a long-lens approach to leader development: Understanding the seeds of leadership. Leadership Quarterly, 22, 459- 470.

Priest, K. L., Kliewer, B. W., Hornung, M., & Youngblood, R. (2018). The role of mentoring, coaching, and advising in developing leadership identity. In L. J. Hastings & C. Kane (Eds.), New Directions for Student Leadership: No. 158. Role of mentoring, coaching, and advising in developing leadership (pp. 9 – 22).

Rogers, C. R. (1959). A theory of therapy, personality, and interpersonal relationships, as developed in the client-centered framework. In S. Koch (Ed.), Psychology: A study of a science: Vol. 3 (pp. 184-256). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Seligman, M. E., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology: An introduction. American Psychologist, 55(1), 5 – 14.

Shaughnessy, S. P., & Coats, M. R. (2019). Leaders are complex: Expanding our understanding of leader identity. In R. E. Riggio (Eds.), What’s wrong with leadership? Improving leadership research and practice (pp. 173 – 188). New York, NY: Routledge.