Main Body

9 Meeting the Challenge of Effective Groups & Teams Membership

Sarah A. Bush & Jason Headrick

INTRODUCTION

When you are assigned to a new team or group in one of your classes, what is the first emotion you feel? For many, this can bring excitement to work with peers and to approach a challenge, project, or assignment creatively. For others, however, the mention of group work brings anxiety and dread. Your reaction is most likely due to previous experiences that you have had working or competing in a team-based environment. Understanding more about the dynamics of teams and the best way to collaborate with others can help you be more successful when working in these environments.

CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to…

- distinguish a group from a team.

- identify the importance of teams in organizations and change processes.

- explain synergy, cohesion, and collaboration on teams.

- provide examples of things you can do personally to work more effectively and efficiently on teams.

- analyze the benefits and barriers to working in teams.

- assess strategies for creating synergy, cohesion, and collaboration on teams ready to engage in your community or workplace.

KEYWORDS: Teams, problem-solving, groups, synergy, cohesion, collaboration

Working in a group or a team can bring about innovation, creativity, a celebration of diversity, and advancements in problem-solving, critical thinking, and building trust. Understanding how to work effectively in groups and teams allows you to engage directly with the ideas behind leadership, which will help prepare you for the workforce. Additionally, teams are increasingly becoming the path to change, as interdisciplinary solutions are required to solve real-world problems impacting our organizations and communities locally and globally.

Organizations use many types of teams to address challenges and create new projects and workgroups. The notion of working in groups and teams prepares individuals to work interdependently with others to accomplish a task or goal. Interdependent work closely relates to the definition of leadership as “a process whereby an individual influences a group of individuals to achieve a common goal” (Northouse, 2019, p. 5). Rather than focusing on influencing others, productive team members focus on how all individuals take on leadership roles and contribute via collaboration. Those who engage in collaborative processes do so to solve problems and make decisions with the input of individuals from multiple perspectives. This diversity leads to synergy; however, there are many obstacles to overcome to achieve synergy and reap the benefits of working collaboratively. Learning more about teams and strategies for collaboration can lead to more effective and efficient teams.

Welcome to the Team!

Research on group processes dates back to the early 1900s (Weingart, 2012); the 1940s marked the beginning of group approaches at the forefront of leadership research (Northouse, 2019). As humans, we gravitate towards work that involves others. We work in groups and teams for various reasons, including dividing tasks to be more efficient, learning from others, and creating solutions from different perspectives; however, individuals, organizations, and scholars have mixed views related to teams (Franz, 2012). Working with a group requires a lot of work, time, and decision-making. It can be hard to get teams to work collaboratively, embrace diversity, overcome conflict, and achieve synergy. This chapter will uncover the benefits and barriers to working in teams and provide strategies to help you personally and professionally increase collaboration in teams.

The Difference Between Groups and Teams

Let’s start by defining groups and teams. Many people use the two terms interchangeably, but there are some key differences. Forsyth (2014) defines a group as “two or more individuals who are connected by and within social relationships” (p. 4). Based on this definition, a group can range from two individuals to many people who are connected based on a shared interest or affiliation (Forsyth, 2014). For instance, a group may march for a cause they believe in, such as women’s rights, and be connected by social affiliation to their shared cause. Groups might also be members of an organization, such as a club or Greek organization.

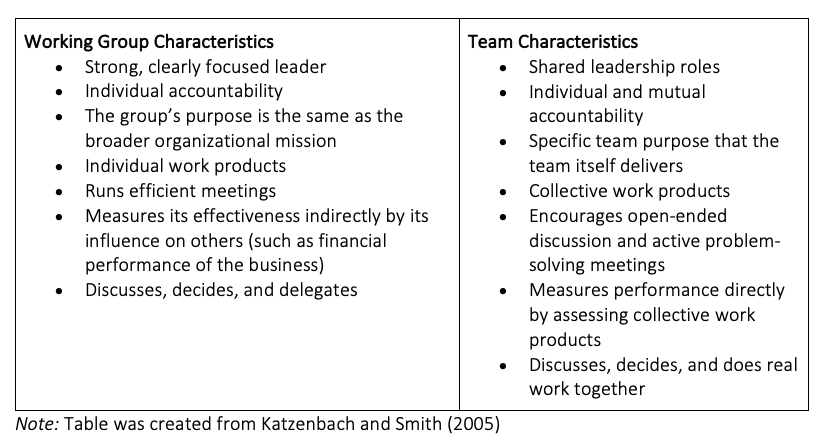

A team is a group that has structure, a focused task, a shared goal, and a relatively high level of “groupness” (Franz, 2012). Katzenbach and Smith (1993) proposed the following definition: “a team is a small number of people with complementary skills who are committed to a common purpose [and] set of performance goals” (p. 112). Therefore, every team is a group, but every group is not a team. See Table 1 for Katzenbach and Smith’s (2005) take on differentiating working groups from teams. Consider the preceding example of the group marching for women’s rights. Every individual involved with the march may have some level of “groupness” based on their shared and vested interest; however, the planning committee for the march implemented their individual talents towards a shared common purpose of planning the march and performance goals and mutual accountability to one another based on the march’s success. Similarly, the executive board or a subcommittee of a Greek chapter tends to function as a team.

Table 1 | Differences between Working Groups and Teams

Differentiating teams from groups is essential to understanding potential processes and outputs, but it is also necessary to explore the age-old question—“are two heads better than one?” The true answer to this is complex—it depends. Research shows that teams who can overcome adversity and other barriers can successfully achieve synergy as individuals and in team environments (Forsyth, 2014; Franz, 2012; Northouse, 2019). When teams can achieve synergy, organizations reap the benefits (Franz, 2012; West, 2004). This reason alone is why many organizations invest both financial and time-based resources in team-based training for their employees. Synergy occurs when the team is something more significant than the sum of its parts. A team’s effectiveness and synergy can play a positive role in their quality of work. Effective teams can lead to the following outcomes (Parker, 1990; West, 2004; Yost & Tucker, 2000):

- Increased productivity and task performance

- More effective use of resources

- Better decision-making and problem-solving

- Better quality products and services

- Improved organizational learning

- Higher employee engagement

- Enhanced member interpersonal skills and compatibility

- Heightened use of emotional intelligence (EI) and practical application of empathy, social skills, motivation, and the ability to resolve differences

- Greater creativity and innovation

Breakdown of Models and Theories

Many theories and models provide insight into how groups and teams work and what makes them effective. In leadership research, team development has been a primary area of study (Fisher, 1970; Hurt & Trombley, 2007; Lewin, 1947; McClure, 2005; McGrath, 1991; Morgan, et al., 1993; Poole, 1981, 1983; Tuckman, 1965; Tuckman & Jensen, 1977; Wheelan, 2009). This chapter will briefly overview the historical models, reveal how they have adapted over time, and guide current application-based models. To fully describe group dynamics and development, we will highlight Tuckman and Jensen’s (1977) Stages of Group Development Model and Fisher’s (1970) Small Group Development Model.

Stages of Group Development Model

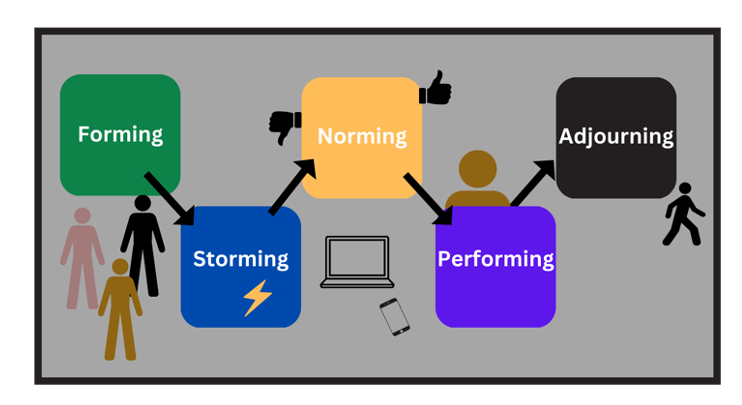

Tuckman’s (1965) Stages of Group Development Model had four initial phases: forming, storming, norming, and performing (see Figure 1). In the forming stage, a group establishes, and the members begin to become familiar with other members, their leaders, their environment, and the preexisting standards in the group (Tuckman, 1965). During storming, conflict arises around interpersonal issues, and the group struggles with adversity, but the norming stage brings group cohesiveness (Tuckman, 1965). Finally, a group’s new-found structure and “groupness” becomes a problem-solving tool, and the group enters the performing stage (Tuckman, 1965). This model demonstrates the formation of group structure and group problem-solving performance. Tuckman and Jensen (1977) revisited the model after researching the life cycles of groups and added a fifth stage, adjourning. During the adjourning phase, the group completes their task and disperses (Tuckman & Jensen, 1977).

Figure 1 | Stages of Team Development (Tuckman & Jensen, 1977)

Small Group Development Model

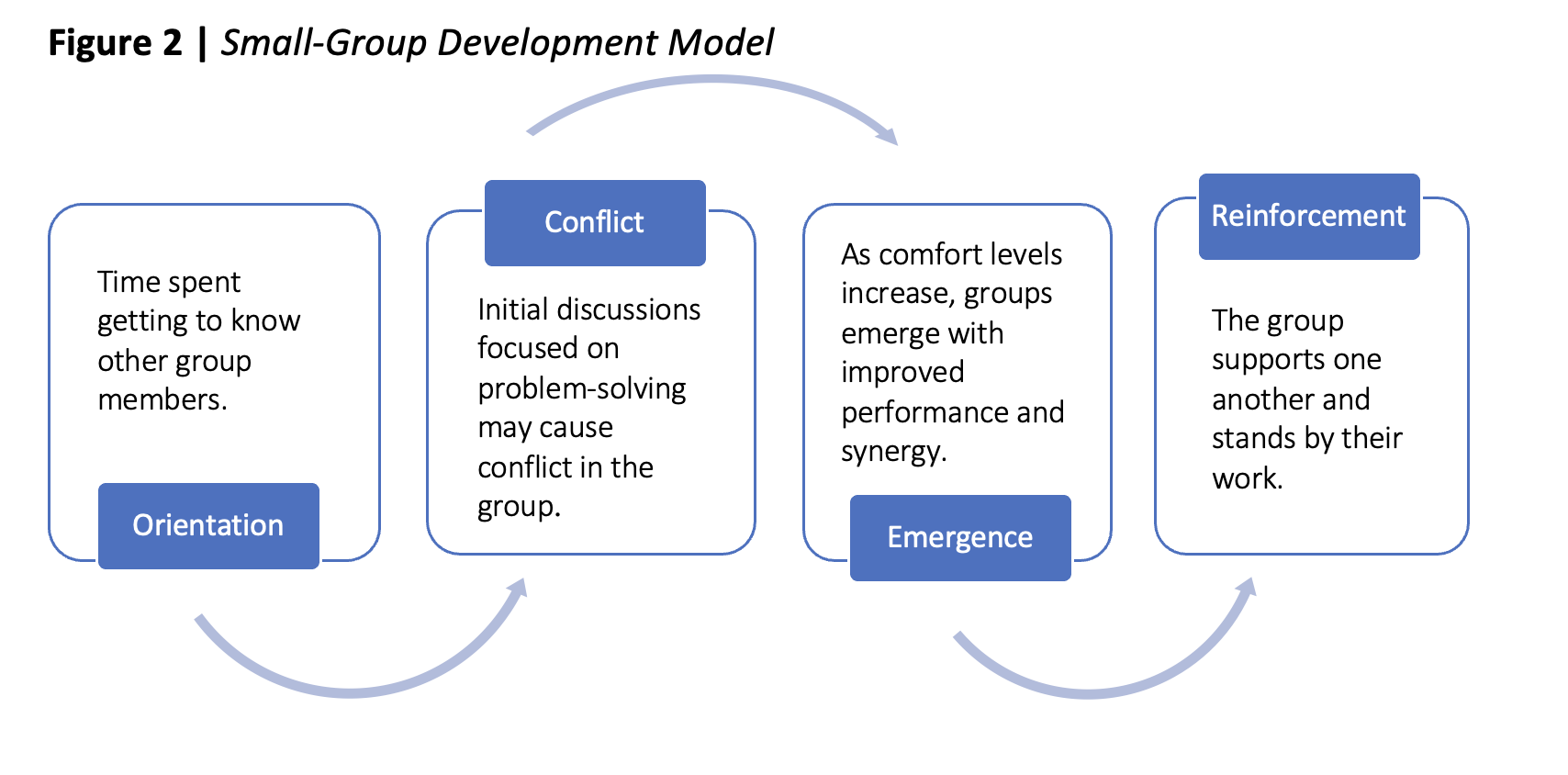

Fisher’s (1970) Small Group Development Model focuses more explicitly on a group’s actions during a decision-making process. This model, similar to Tuckman’s (1965) and Tuckman & Jensen’s (1977) models, contributes to group processing. The model deals mainly with communication and interactions and includes four phases: orientation, conflict, emergence, and reinforcement (see Figure 2).

Orientation: During the orientation phase, group members spend time getting to know each other, and a bit of tension may be present due to individuals being uncomfortable communicating with each other (Fisher, 1970). When we meet with a group or team members for the first time, it is important to focus time on introductions, getting to know one another, and discussing the group’s goals. Establishing some of the norms and standards for the group/team can start the time together more positively. Deciding how the group will communicate (e.g., exchanging phone numbers and email addresses) is essential during the orientation period.

Conflict: The conflict phase occurs from tension in the group when individuals debate and discuss possible solutions to the problems at hand (Fisher, 1970). Notably, conflict can benefit all members in discussing rules or norms the group or team will have when future conflict occurs. These expectations help establish the group’s footing and prepare them for future decision-making and conflict. This chapter provides strategies to move through and process conflict.

Emergence: As the individuals become more comfortable with each other and a defined group structure is formed, the emergence phase occurs (Fisher, 1970). The emergence phase helps groups and teams set work patterns that increase performance and help achieve goals. Consider this stage like a butterfly coming out of its cocoon – when it emerges, it’s ready to flutter around and get to work. When a group or team develops, it shows that the efforts to reach synergy have happened, and the group or team begins working together effectively. For this to happen, the group or team may need to reevaluate the roles and duties of all involved and make adjustments so the best work is moving forward. A commitment to making adjustments means that individuals will put the group’s greater good ahead of their personal needs and decisions.

Reinforcement: Finally, through reinforcement, all individuals reach a consensus to support the decision made through both verbal and nonverbal transmissions (Fisher, 1970). This stage means that the group or team is willing to help and stand behind the assignment, work, and decisions made through working together.

Each phase of Fisher’s model is essential for groups to consider as they navigate their work. By using the stages as a blueprint, the groups and teams can address conflict and be effective in their decision-making and other team responsibilities.

The Barriers We Face

Over the years, models have continued to develop on group processes, and many still involve stages; however, newer models are more flexible in the progression of the phases, recognizing the issues with the prescribed straight-forward team and group processes (McGrath, 1991; Morgan et al., 1993; Poole, 1983; Wheelan, 2009). In these models, teams can backtrack through phases or skip stages. These models recognize changing social relationships involved in a team and how dynamic teams are in a state of continual evolution.

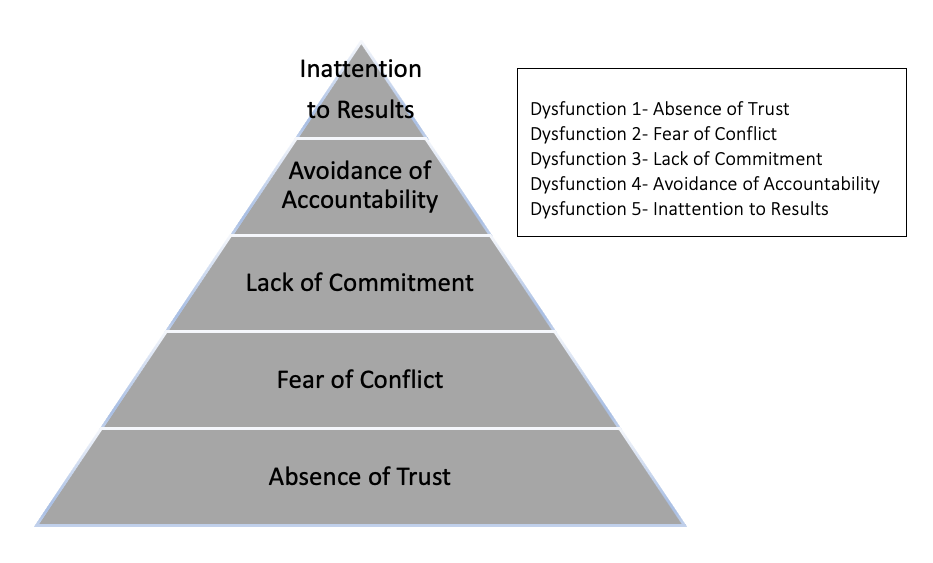

Lencioni (2002) created a model that considers barriers teams must overcome, identifying how they can cause a chain reaction contributing to other obstacles. Lencioni’s (2002) Five Dysfunctions of a Team Model identifies these barriers as primary issues when working in a team. In this model, the dysfunctions are interrelated and build upon one another (see Figure 3).

Figure 3 | Lencioni’s (2002) Five Dysfunctions of a Team Pyramid

The presence of a dysfunction sparks a chain reaction of events causing other dysfunctions to occur. So, even the existence of just one dysfunction will often be detrimental to teamwork (Lencioni, 2002).

Absence of trust: The first dysfunction, lack of trust, is based upon vulnerability (Lencioni, 2002). Lencioni (2002) described group trust as “the confidence among team members that their peers’ intentions are good and that there is no reason to be protective or careful around the group” (p. 196). Hence, team members must be vulnerable with each other in acknowledging their shortcomings, making mistakes without judgment, and requesting aid from others (Lencioni, 2002). A team that shares mutual trust understands each member’s distinctive attributes and how those attributes add value to the group. As the model’s foundation, a team that lacks trust will make teamwork nearly impossible (Lencioni, 2002).

Fear of conflict: Without trust, a team will not debate when problem-solving (Lencioni, 2002), which leads to the second dysfunction, fear of conflict. Although we often think of conflict negatively, any strong relationship must undergo conflict to succeed (Lencioni, 2002); however, productive conflict is understood to be healthy debate or arguments over concepts and ideas. It avoids “personality-focused, mean-spirited attacks” (Lencioni, 2002, p. 202).

Lack of commitment: Individuals in a group need to feel heard before committing to a decision, whether it was their idea or not (Lencioni, 2002). The third dysfunction, lack of commitment, relates to team members not supporting or feeling confident in decisions made by the team (Lencioni, 2002). Buy-in from all members allows teams to stand behind decisions, whether there is a great deal of risk involved or not (Lencioni, 2002). All team members must fully support decisions and understand their role in a productive team.

Avoidance of accountability: The fourth dysfunction, avoidance of responsibility, occurs when team members are unwilling to approach their peers about their performance or behaviors, harming the overall team (Lencioni, 2002). At times, the fear of conflict causes individuals with strong relationships to ignore the poor performance of other team members (Lencioni, 2002). Lencioni (2002) stated that ignoring negative behaviors leads to resentment. When peers do not hold each other accountable, group structure lacks, and some form of structure is vital for a team (Lencioni, 2002).

Inattention to details: Suppose team structure breaks and all individuals are not contributing. In that case, team members focus on their own needs and personal goals instead of the overall team goals (Lencioni, 2002). The fifth dysfunction, inattention to details, occurs when team members focus their attention on “something other than the collective goals of the group” (Lencioni, 2002, p. 216).

Teams must have overarching goals in which all members invest. Members of a successful team must trust each other, engage in conflict, commit to group decisions, hold their peers accountable, and achieve results (Lencioni, 2002).

Barriers to Achieving Synergy

Teams often have so many barriers to overcome that they struggle with productivity, efficiency, problem-solving, organizational learning, and creativity. Team success is rare (Coutu & Beschloss, 2009). This lack of success is due to an inability to overcome barriers and dysfunctions, as described through Lencioni’s (2002) model. These dysfunctions provide an overview of obstacles for teams to achieve synergy and perform, but several other difficulties related to communication, interpersonal matters, problem-solving, and cohesion also plague teams (Franz, 2012). The first step to overcoming these barriers is to identify the overarching problem. For instance, if your team is having communication issues and information is withheld from the group, you can start by examining if the issue is a communication issue or an issue related to trust. Poor communication can result in deteriorating trust, and a lack of trust can result in poor communication. Understanding the basis for the barrier and conflict helps you know which issue to approach first.

Cohesion & Collaboration

The intended outcome for most teams is to achieve synergy, which requires collaboration. A team cannot be greater than the sum of its parts without true collaboration. Collaboration is a process that involves a group working to solve a problem or make a decision that requires shared goals and the sharing of responsibility, authority, and accountability (Franz, 2012; Higher Education Research Institute, 1996; Komives & Wagner, 2017; Liedtka, 1996; Schrage, 1990). The key to understanding collaboration is that the process and outcomes are all shared. It is more than delegating tasks and working separately towards a common purpose. Collaboration includes the following:

- Human relationships and how people relate to each other

- A process for developing common goals and purpose

- Shared responsibility, authority, and accountability in achieving goals

- Creating synergy by utilizing multiple perspectives and strengths of team members (Komives & Wagner, 2017)

This process can be challenging to achieve as these teams need to overcome the five dysfunctions, have high levels of communication, and must dedicate time to increasing cohesion.

Cohesion from both a task and social aspect is essential to engage in collaborative processes (Franz, 2012). Cohesion is grounded in the attraction of members to the group and the group’s work. Cohesion can be threatened by the size of a group, individuals’ interest in the tasks, tasks being completed individually rather than shared, and the diversity of experiences and personalities. To increase cohesion, teams should establish a group identity, emphasize teamwork, recognize and reward contributions, and respect all group members (Franz, 2012). Cohesion involves both personal and team-level efforts.

Strategies for Increasing Collaboration, Cohesion, and Synergy

At this point, you may be asking – “So what can I do to increase the likelihood of success for a team?” As mentioned prior, your team can dedicate time to developing relationships and increasing trust. For example, you should spend time at the beginning of meetings to get to know one another’s interests, backgrounds, experiences, etc. Success also includes discussing each person’s interest in the project or work, which helps determine what personal goals exist even before discussing shared goals. Be open to learning and listening to others. It’s also essential to share ownership for the process and fully be invested in the group’s decisions whether there is success or room for improvement. Those who are great team members celebrate the team’s successes and other individuals and take responsibility for failures, even when they weren’t involved (Komives & Wagner, 2017). Teams that fail should fail together, and teams that succeed should share in accomplishments.

You can also be seen as trustworthy by being dependable, helping other team members, sharing your views, and encouraging others to do the same (Komives & Wagner, 2017). Building trust allows groups to focus on the process of collaboration. Collaboration often starts with creating a shared group identity and then developing shared goals and purpose. Through this process, communication is critical and should be a focus at all times. Diversity is also important and requires that members form groups with people who have different perspectives that engage in dialogue and express their views openly without fear of judgment. Work with your team to set team rules to promote respect. When groups uphold these strategies, cohesion increases, and teams can achieve collaboration and synergy (Franz, 2012; Komives & Wagner, 2017). Use your knowledge, experience, and skills to make yourself a better group member and to help bring out the best in others.

QUESTIONS FOR JOURNALING OR DISCUSSION

- When have your experiences with teams been positive? How have other experiences been negative? What content from this chapter helped you understand what you might have done differently during that negative team experience?

- What is the role of the individual in a group or team?

- How does a solid team foundation help address conflict or other challenges a group or team faces?

- Which model of teamwork effectiveness do you think you are likely to use in the future? How can you help others get on board with those steps or strategies?

- Reflect on the necessary skills you develop through your involvement with a group or team. Why are these skills needed for the future? How can you use them to build your leadership capacity?

ACTIVITIES

No Good Path Activity—A Case Study on Collaborating to Provide Solutions

Chestnut Lake State College is a medium-sized university with about 13,000 students located in Ramberville, a town with approximately 45,000 people. This quaint city is known for its walkability, history, and friendliness. Additionally, it is one of the best places to raise a family. Historically, Chestnut Lake State College has maintained a good relationship with Ramberville. The residents enjoy attending sporting events and interacting with students.

Five years ago, Chestnut Lake State College set a goal to increase the student population by 5,000 over the next ten years. As the student population is growing, student housing is expanding. Previously, nightlife and student housing had all been located on the south side of the campus, directly connecting to the campus. New and attractive student housing options are being built on the north side of campus, behind several residential housing blocks. Over the last year, residents in this area have made noise complaints about students walking through their neighborhoods late at night. These noise complaints occur because the most direct path from nightlife to the new student housing options is through several local areas. Recently, reports of vandalism and stolen items from lawns have also been made.

The relationship between Ramberville and Chestnut Lake State College is quickly deteriorating as the university and town leadership fail to respond to the complaints. The local police have been attempting to patrol the area more frequently but always seem to get called away to respond to other calls at this time. Ramberville cannot afford to increase its staffing based on the city’s current budget. A bus system drops the students off downtown but makes the last run at 11:30 pm. Additionally, cabs and rideshare services are hard to come by in the local area. Typically, walking is the fastest way to get home. The university also sponsors a safe-walk system, but it does not extend to these new housing areas.

The university must respond with some proposed actions and initiatives to maintain its relationship with Ramberville. They’ve decided to create a joint task force with the local community to develop potential solutions. Work through the prompts below and be ready to discuss your answers.

- How can the university create a diverse team of community and student leaders? Who should serve on the team? Why?

- How will team diversity help achieve synergy?

- How can you go about setting up the team process to achieve synergy?

- How can the leader of the team overcome the five dysfunctions?

- Create a plan of action for developing a solution to the current issue.

“Hidden Agendas” Activity

Instructions:

Place individuals in teams of 6-7. Give them the common task of building a wall (using LEGO® blocks, note cards, etc.). The wall should be four blocks high and six blocks wide. Then hand out cards with specific goals for each participant. This card represents their personal hidden agenda. The participants should never reveal what is on their card or show their card to another individual. Let the team members work through the activity and do their best to solve the group assignment while satisfying their hidden agenda; however, it should be clear that their personal agenda is always more important than the team agenda.

You can conduct the activity in two ways. The first is to make the activity solvable and provide enough time for them to develop the solution. The second is to make the solution impossible and stop the activity after a set time. The aim of both is to discuss how a lack of commitment to a shared goal and hidden personal agendas can get in the way of collaboration.

Some examples of hidden agenda tasks using colored bricks or blocks as building materials:

- Ensure there are three red bricks on each row

- Ensure no red brick touches a yellow one

- Ensure a blue brick touches a yellow brick on each row

- Ensure every row contains two yellow bricks

- Ensure there is a vertical line of touching white bricks, one block wide, from top to bottom

- Ensure every row has at least one double-block brick

- Ensure that all green bricks are at the end of the row

Reflection:

Reflect by discussing how hidden agendas impact overall group work. Below are some prompts to help start your reflections.

- What was the cause of most of the issues?

- How do hidden agendas impact group work?

- Provide an example of a time you worked with individuals with hidden agendas.

- How do hidden agendas impact trust?

- How could you work through hidden agendas?

- Do you see how this demonstrates the storming phase?

- o Discuss how teams move to the norming phase by working through hidden agendas and creating team-focused goals.

- Did you experience or observe any other team-based components in this activity?

Reflection Questions

- What was the best experience you’ve ever had working on a team? What made the group so enjoyable?

- In this experience, how did your team progress through Tuckman and Jensen’s (1977) Stages of Group Development Model or Fisher’s (1970) Small Group Development Model?

- How did your team build cohesion and collaborate?

- Did your team achieve synergy? How do you know?

- What was the worst experience you’ve ever had working on a team? What made the group so challenging?

- What dysfunctions from Lencioni’s (2002) Five Dysfunctions were present?

- How could you, as an individual, increase cohesion and collaboration on your team?

- What strategies could your team have used to increase cohesion and collaboration?

Suggested Videos

Stages of group development as told through the Fellowship of the Ring: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ysWWGf8VsOg&t=11s

Stages of group development: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H8gryfMB2P4

Five Dysfunctions of a Team: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wHpB1EBufFo&t=12s

Forgetting the pecking order at work: https://www.ted.com/talks/margaret_heffernan_forget_the_pecking_order_at_work

REFERENCES

Coutu, D., & Beschloss, M. (2009). Why teams don’t work. Harvard Business Review, 87(5), 98–105. https://hbr.org/2009/05/why-teams-dont-work

Fisher, B. A. (1970). Decision emergence: Phases in group decision-making. Speech Monographs, 37(1), 53–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637757009375649

Forsyth, D. R. (2014). Group dynamics. Wadsworth.

Franz, T. M. (2012). Group dynamics and team interventions: Understanding and improving team performance. Wiley-Blackwell.

Higher Education Research Institute. (1996). A Social Change Model of Leadership Development (Version III). UCLA. https://www.heri.ucla.edu/PDFs/pubs/ASocialChangeModelofLeadershipDevelopment.pdf

Hurt, A. C., & Trombley, S. M. (2007). The punctuated-Tuckman: Towards a new group development model. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED504567.pdf

Katzenbach, J. R., & Smith, D. K. (1993). The wisdom of teams: Creating the high-performance organization. Harvard Business School.

Katzenbach, J. R., & Smith, D. K. (2005). The discipline of teams. Harvard Business Review, 83(7/8), 162–171. https://hbr.org/1993/03/the-discipline-of-teams-2

Komives, S. R., & Wagner, W. (Eds.). (2017). Leadership for a better world: Understanding the Social Change Model of Leadership Development (2nd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Lencioni, P. (2002). The five dysfunctions of a team. Jossey-Bass.

Lewin, K. (1947). Frontiers in group dynamics: Concept, method and reality in social science, social equilibria and social change. Human Relations, 1(2), 143–153. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872674700100201

Liedtka, J. M. (1996). Collaborating across lines of business for competitive advantage. Academy of Management Perspectives, 10(2), 20–34. https://doi.org/10.5465/ame.1996.9606161550

McClure, B. A. (2005). Putting a new spin on groups: The science of chaos (2nd ed.). Taylor and Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781410611932

McGrath, J. (1991). Time, interaction, and performance (TIP): A theory of groups. Small-Group Research, 22(2), 147–174. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046496491222001

Morgan, B. B., Salas, E., & Glickman A. (1993). An analysis of team evolution and maturation. The Journal of General Psychology, 120(3), 277–291. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221309.1993.9711148

Northouse, P. G. (2019). Leadership: Theory and practice (8th ed). Sage.

Parker, G. M. (1990). Team players and teamwork. Jossey-Bass.

Poole, M. S. (1981). Decision development in small groups I: A comparison of two models. Communications Monographs, 48(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637758109376044

Poole, M. S. (1983). Decision development in small groups II: A study of multiple sequences in decision making. Communication Monographs, 50(3), 206–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637758309390165

Schrage, M. (1990). Shared minds: The new technologies of collaboration. Random House.

Tuckman, B. W. (1965). Developmental sequence in small groups. Psychological Bulletin, 63(6), 384–399. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0022100

Tuckman, B. W., & Jensen, M. A. C. (1977). Stages of small-group development revisited. Groups and Organization Management, 2(4), 419–427. https://doi.org/10.1177/105960117700200404

Weingart, L. R. (2012). Studying dynamics within groups. In M. A. Neale & E. A. Mannix (Eds.), Looking back, moving forward: A review of group and team-based research (pp. 1–25), Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1534-0856(2012)0000015004

West, M. A. (2004). Effective teamwork: Practical lessons from organizational research. Wiley-Blackwell.

Wheelan, S. A. (2009). Group size, group development, and group productivity. Small-Group Research, 40(2), 247–262. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046496408328703

Yost, C. A., & Tucker, M. L. (2000). Are effective teams more emotionally intelligent? Confirming the importance of effective communication in teams. Delta Pi Epsilon Journal, 42(2), 101.