Main Body

11 Managing Conflict Expectations

Jason Headrick & Ashlee K. Young

INTRODUCTION

Whether you know this quote from Shakespeare or heard Nick Fury utter it in Spider-Man: Far from Home, this phrase is frequently mentioned in reference to the responsibilities borne by a leader. Those charged with a position of leadership can carry a heavy burden that takes an emotional toll. A person in charge or in a leadership role is often looked to for answers, specifically when held accountable in conflict situations where there is no clear-cut resolution.

This chapter will address types of conflict, frame ways of viewing conflict, and finish with some strategies you might consider working through conflicts you encounter.

CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to…

- understand conflict and how to engage in constructive conversations.

- better understand models of managing conflict and how to use them in your own practices.

- define conflict and recognize the goal-based and relational concerns that must be taken into account within conflict situations.

- identify the benefits of conflict.

- reflect upon conflict that has happened in your life and evaluate the strategies you used to work through it.

KEYWORDS: Conflict management, conflict approach, conflict resolution, disagreement, conflict-agility

Conflict management is rooted in the acknowledgment that conflict is inevitable when people and groups rely on one another. Particularly in a college leadership setting, conflict is not always a bad thing and can, in fact, be seen as a positive force for growth if harnessed properly. In its positive form, conflict can help maintain an optimum level of stimulation and activation among organizational members, contribute to an organization’s adaptive and innovative capabilities, and serve as a basic source of feedback regarding critical relationships, the distribution of power, and the problems that require management attention (Miles, 1980). We all manage conflict differently—some people avoid it, some people tolerate it, and some thrive in it. Regardless, we all have to face conflict in our lives, and this chapter is written to help prepare you.

Defining Conflict

Is conflict the same as an argument or disagreement with a family member or co-worker? Or does conflict have to occur on a larger scale, like a battle? The World Book Dictionary defines a conflict as a fight, struggle, battle, disagreement, dispute, or quarrel (Barnhart & Barnhart, 1986). Conflict can develop from a disagreement centered on status, agenda, or a certain context involving two or more parties. Although the nature of a conflict can take on many meanings, Johnson and Johnson (2005) highlight two major concerns that must be taken into account when involved in a conflict situation:

- Reaching an agreement that satisfies our/the group’s wants and meets our goals. We find ourselves in conflict because we have a goal or interest that conflicts with another person’s goal or interest.

- Maintaining an appropriate relationship with the other person or group. What is the nature of the relationship? Is it a temporary relationship or is it permanent?

Sources of Conflict

Unless you live in a solo bubble, you will experience conflict at some point in your life. Conflict can occur between people in all kinds of interpersonal relationships and all types of social settings, and sources of conflict are almost always relational in some form. Katz (1965) theorized three main sources of conflict: economic, value, and power.

Economic conflict: This source of conflict involves competing motives to attain scarce resources. You may have heard the phrase “wanting a piece of the pie.” Deciding how to divide out that “pie,” or resources, can lead to disagreement about how to gain the most or maximize perceived limited resources.

Value conflict: This source of conflict is rooted in an incompatibility in personal beliefs, morals, and values. During a value-based conflict, each side tries to assert the “rightness” in their way of life – including preferences, principles, and practices.

Power conflict: This source of conflict occurs when each party wishes to maintain or maximize their influence. Power enters all conflict because at the heart of the conflict is a need for control. It should be noted within this type of conflict that it is impossible for one party to be advantaged without one being disadvantaged.

Most conflicts are not purely one type but may involve a mixture of sources, including miscommunication. Each party has different perceptions of the facts or a misunderstanding of what is being communicated, and a lack of clarity can easily lead to conflict.

Understanding The Role of Conflict

Lencioni (2002) identifies “fear of conflict,” or failing to recognize the power of “productive conflict in order to grow,” as one of the most common organizational maladies (p.202). Fearing conflict lends itself to an outright rejection of conflict. In a conflict-negative group, conflicts are suppressed and avoided, and when they occur, they are managed in destructive ways (Tjosvold, 1991). People avoid disagreements and friction with others because of this negative association; however, as Deutsch (1994) points out, “conflict can be constructive as well as destructive” (p. 13).

Leaders will often turn away from conflict and never realize its potential for promoting growth rather than disorder (Feirsen & Weitzman, 2021). Recognizing the power of conflict as an impetus for change, conflict can be good for individuals, organizations, and systems. In a conflict-positive group, conflicts are encouraged and managed constructively to maximize their potential in enhancing the quality of decision-making and problem-solving. Group members create, encourage, and support the possibility of conflict (Tjosvold, 1991). When we are forced to make decisions that can impact others, we tap into our subconscious and our own approaches to emotional intelligence. Many of us have a hard time thinking about change, but it can provide renewed energy and motivation when we might be stuck in a set pattern at work, in our collaborations with others, and in thinking about problem-solving strategies.

The Benefits of Conflict: Improving Conflict-Agility and Other Necessary Skills

Feirsen and Weitzman (2021) describe conflict-agility as the ability to utilize effective communication strategies for reducing strife when harnessing conflict to improve outcomes and relationships. Depersonalizing the conflict and respecting everyone involved in the conflict requires careful framing of language. For example, the phrase “let’s explore options” signals that there could be multiple ways to move forward with the issue. This phrasing confirms that multiple ideas, not the specific people involved in developing the ideas, are to be evaluated, thus depersonalizing the core issue.

Specifically, conflict management skills are developed over time. No one is born an expert on how to resolve conflicts. Our experiences build over time with this skill, just like many others. Dealing with conflict is not only about decision-making and how we communicate with others; addressing conflict allows us to work on additional skills along the way, too. Some skills-based research has shown that using empathy and compassion for others has more positive effects on interpersonal relationships, particularly when dealing with conflict (Klimecki, 2019). Katz and colleagues (2020) propose that engaging with conflict can lead to learning and skill development, changes in the way information is shared among groups, enhancements to reflective listening and problem-solving, and a greater confidence in the way you communicate your thoughts, feelings, and concerns directly with others while being mindful of self-esteem and the relationships you maintain with others. Possessing knowledge about the way others engage in conflict, including individual and gender differences, is a critical skill to be successful in the workplace (Steen & Shinkai, 2020).

Leader Log

Two scenarios are listed below. Read both and consider ways you might try to work through the conflict presented in each situation. At the end of the chapter, you will have the opportunity to consider your approach to resolving the conflict in these and additional scenarios.

Scenario 1

Serena is planning an alumni dinner on behalf of the student advisory board for the college. Funds have been allocated to bring in a speaker. Serena is all set to make an offer to a speaker when Joe finds out that the speaker has been exposed on Twitter as having a history of degrading a group of people based on their racial identity. Given the timeframe, if the organization does not book this speaker, it is unlikely there will be enough time to book someone else, and the college will have to cancel the dinner.

As the chair of the student advisory board, you decide to have your officer team meet together to discuss options. During the meeting, the group is divided. Half of the team still wants to bring the speaker to campus because they would rather the dinner moves forward than not have it at all. The other half of the team does not want to bring the speaker to campus and prefers to cancel the event.

Scenario 2

You are on a planning committee for a campus cultural event. Someone suggests the group offer halal chicken to meet the needs of Islamic students attending. The rest of the committee is dismissive because of the cost and possible difficulty obtaining the chicken.

Approaches to Resolving Conflict

Conflict can bring out the best (or the worst) in people. As a leader, you must be willing to engage in the often work that comes with conflict. This can be the way you guide the conversation centered around civility, but it can also mean you have the leadership ability to think beyond the immediate conflict you are experiencing and begin to see the bigger picture or end goal that you are working towards. This step helps you see why addressing the conflict is important to the work you are doing. Conflict is not always resolved overnight, and there may be instances when the work can seem too big to take on. Much has been written and researched centered on conflict and effective strategies we can use to address the “elephant in the room.” This section will give you two approaches to consider when addressing conflict in your life.

CHAPTER SPOTLIGHT OR CASE

As told by Kara, Associate Director of Student Advocacy & Support, University of Nebraska-Lincoln

Describe your current or previous roles that have allowed you to practice conflict mediation.

My current role is within the Division of Student Affairs at a University, focusing on providing individualized support to students experiencing health concerns or difficult personal circumstances. Many of the students I work with are faced with difficult decisions, such as whether or not to stay enrolled in school during a health crisis. These decisions can be complex, emotional, and just plain hard. Some students make these decisions independently, while others involve family members. Conflict can arise when the student and their family see the situation differently or disagree on what path to take. I have served as a mediator in these situations dozens of times.

In your experience, when is there a need for mediation of conflict?

Mediation is helpful when one of the two following circumstances are present: (1) student and family are unable to identify a solution, or (2) trust has been broken because the student and family member disagreed on something in the past.

When mediating a conflict, what strategies have you utilized?

- Mediation strategies I use are:

- Host the conversation in a neutral place

- Start by framing the key issues and setting the tone for honest, patient, and collaborative conversation

- Identify common goals, such as supporting the student’s well-being and academic success

- Ensure opportunities are present for both parties to express thoughts and ask questions

What conditions do you believe should be present to allow for effective discussion of difficult issues?

All parties in the discussion must be willing to listen and share honestly. It helps me to have access to information related to the decision and to have the ability to ask questions. Ideally, trust is present in the discussion of difficult issues. We know this is not always the case. If trust does not exist, the focus on common goals is helpful. Mediators must be willing to interject and redirect if emotions become too heightened for productive conversation or if it goes too far off-topic.

What advice do you have for student leaders when navigating peer-to-peer conflicts?

Navigating conflict is an important skill, and building a skill requires intention. Reflection after conflict is important because there is something to be learned from every conflict that has the potential to increase your effectiveness in the future. Focus on your shared goals and how to achieve them, whether they are about maintaining a friendship or completing a group project. If the conflict is escalating, do not be afraid to hit “pause” on the interaction with an agreement to revisit it when everyone is feeling calmer. Use your voice and share your perspective, but never forget that others need their voice and perspectives heard, too.

Choose Your Conflict Management Adventure: Five Basic Strategies

Coaching student leaders through their reaction to a conflict requires an understanding that one size does not fit all. Dealing with conflict is frequently an individualized process and an emotionally charged one. It is human nature to respond with what feels most natural, and when faced with a conflict, people tend to fall back on strategies acquired during childhood which can act as a type of automatic response. Depending on where you are in the process of reflecting on pre-existing strategies, it may be beneficial to start with a foundational understanding of some straightforward approaches.

Determining which strategy is appropriate given one’s goals and relationship with the other party or group involved in the conflict is crucial. Often utilized in educational and business settings, Johnson and Johnson (2017, pp.379–380) have identified five basic strategies for managing conflict: problem-solving negotiations, smoothing, forcing or win-lose negotiations, compromising, and withdrawing.

Strategy 1: Problem-Solving Negotiations

This strategy is also known as “confronting the conflict.” Problem-solving negotiation is best practiced when both the goal and the relationship with the other party or group in the conflict situation are highly valued to you. This strategy encourages honesty about underlying motivations and interests with the goal of working together to find a solution. Confronting the conflict and seeking to identify a way to solve the problem together ensures that both you and the other party or group member are able to achieve your goals while resolving tensions and negative feelings.

Because this strategy requires a high level of trust and a commitment to maintaining the relationship long-term, this can be seen as time consuming and risky; therefore, it should not be used if a decision is urgent or if there is not enough respect or communication among the group for problem-solving negotiations to be intentionally discussed.

Strategy 2: Smoothing

Employed when the relationship is more important than the goal, smoothing demands self-sacrifice. Smoothing requires you to give up your own goal to maintain a relationship at the highest quality possible by accommodating the needs of the other party or group and prioritizing them over your own. This strategy should be used when the other party’s perspective and interests in relation to the conflict are more important than yours, or if you discover you are wrong about the issue. It should not be used if you are equally invested in the outcome.

Strategy 3: Forcing or Win-Lose Negotiations

When the goal is important and you perceive the relationship to be of little consequence, forcing is a power move of a strategy which essentially elevates your own concerns at the expense of others. This strategy involves the use of force, so the other party or group will concede. Forcing tactics commonly used to “win” the conflict often include threats, physical and verbal aggression, or imposing penalties that will be withdrawn if the other party gives in. Win-lose negotiation tactics include presenting persuasive, “unbeatable” arguments, imposing a hard deadline, or making demands that far exceed acceptability.

This strategy requires the ability to determine if winning the conflict is ultimately beneficial to all of the parties involved. This strategy should be used only when you know you are unequivocally right. It will not enhance a relationship or allow for a cooperative working environment.

Strategy 4: Compromising

Meeting in the middle is at the heart of the compromise strategy. When both the goal and the relationship are somewhat important to you, and it appears that both you and the other party or group cannot get what you fully want, you may need to give up some of your goals and sacrifice part of the relationship to reach an agreement that partially satisfies both parties.

This strategy is best used when those involved in the conflict are willing to be flexible and are okay with getting a piece of what they wanted but not all. Compromising differs from smoothing because each party gives something up instead of one party giving in to the other. This strategy should not be used if parties are not equally invested or if you want to develop a long-term solution to a complex issue. For example, if you and a roommate have decided to part ways, deciding to compromise and share custody of a couch is likely not a long-term fix as the likelihood of moving a couch back and forth every couple of months is not feasible.

Strategy 5: Withdrawing

Failing to address a conflict through the process of withdrawing means avoiding the conflict because you refuse to engage with the conflict. By withdrawing, you communicate that you value neither the relationship nor the goal and, therefore, choose to avoid the issue and the person or group altogether.

If there are concerns about personal safety, other issues are more pressing, you are underprepared to tackle the conflict, or perhaps feel too emotionally involved, circumstances may dictate that withdrawing is the most appropriate strategy; however, withdrawing may not be appropriate when the issue centered within the conflict is considered very important, or the conflict will continue to escalate by avoiding a resolution. Particularly within interpersonal conflicts, “ghosting,” or disappearing from the interaction, can have lasting negative consequences.

Leader Log: Based upon your historical engagement with managing conflict, you may identify more with the following associations:

- Problem-solving negotiations → collaboration

- Smoothing → accommodation

- Forcing or win-lose negotiations → competition

- Compromising → giving up

- Withdrawing → avoidance, ghosting

Reflect on which of these strategies, if any, you tend to fall back on. What have you observed about approaching conflict that you believe has influenced this inclination? Discuss with a partner.

Leveling Up: Constructive Conflict Approach

Constructive conflict gives you the opportunity to talk openly and respectfully about the presenting conflict with all parties involved. The most important thing to note about constructive conflict is that it is a mutual attempt to understand one another’s perspectives and create the best solution. Listening to others is a skill, and this might be an area that many need to practice. It can take time to develop how we listen to others and approach these difficult conversations. Follett (2011) asserts that if we do not focus on integrating ideas and views to deal with conflict, we are only compromising in our solution, leading to repeated behavior and conflict. The constructive conflict approach is interconnected with the conflict management styles of Thomas and Kilmann (1974). While this research dates back several decades, their model for identifying ways to manage conflict and produce resolution is widely used today (Ma et al., 2008). The 4-step approach is outlined in this section and is used across the human resources field as a suggested way to settle disputes and build your conflict-agility skills along the way.

Step 1—Explore: For those of you who are familiar with leadership theory, Step 1 looks a lot like certain aspects of adaptive leadership. Adaptive leadership is a way to lead and process change and adaptation by identifying challenges in the workplace, community, or another social system. Part of engaging as an adaptive leader is to take a step back and put yourself “on the balcony” (Heifetz, 1994). Step 1 seeks the same strategy. During this step, you will ask others for feedback and input. This feedback should be relevant to addressing the conflict and not as a means of voicing your opinion or complaining about others. This is counterproductive to resolving the conflict. You will also identify stakeholders and those who have something to gain or lose in resolving the conflict. Who will this decision impact? They are your stakeholders. The last part of this step is to look for sources of conflict. Are there common occurrences that cause the conflict to begin, or are there commonalities in people, places, policies, or other things that might be attributed as the source of conflict?

Step 2—Plan: Developing a plan is an important step in your approach to addressing and resolving conflict. This step allows you to evaluate your own process to address conflict and to importantly self-reflect on how you have engaged in conflict resolution in the past. Consider reflecting on how you deal with conflict and with what emotions you might enter into this process at the outset. Do you go into this process with a negative or positive attitude? Perhaps you have heard the saying, “attitude is everything,”; it turns out this saying is accurate. Research has shown that the positive or negative approaches people bring to decision-making and behavior directly contribute to their success in goal completion (Brügger & Höchli, 2019). Challenging conflict with a belief that you will be successful in resolving the conflict leads to a greater likelihood that you will meet this goal.

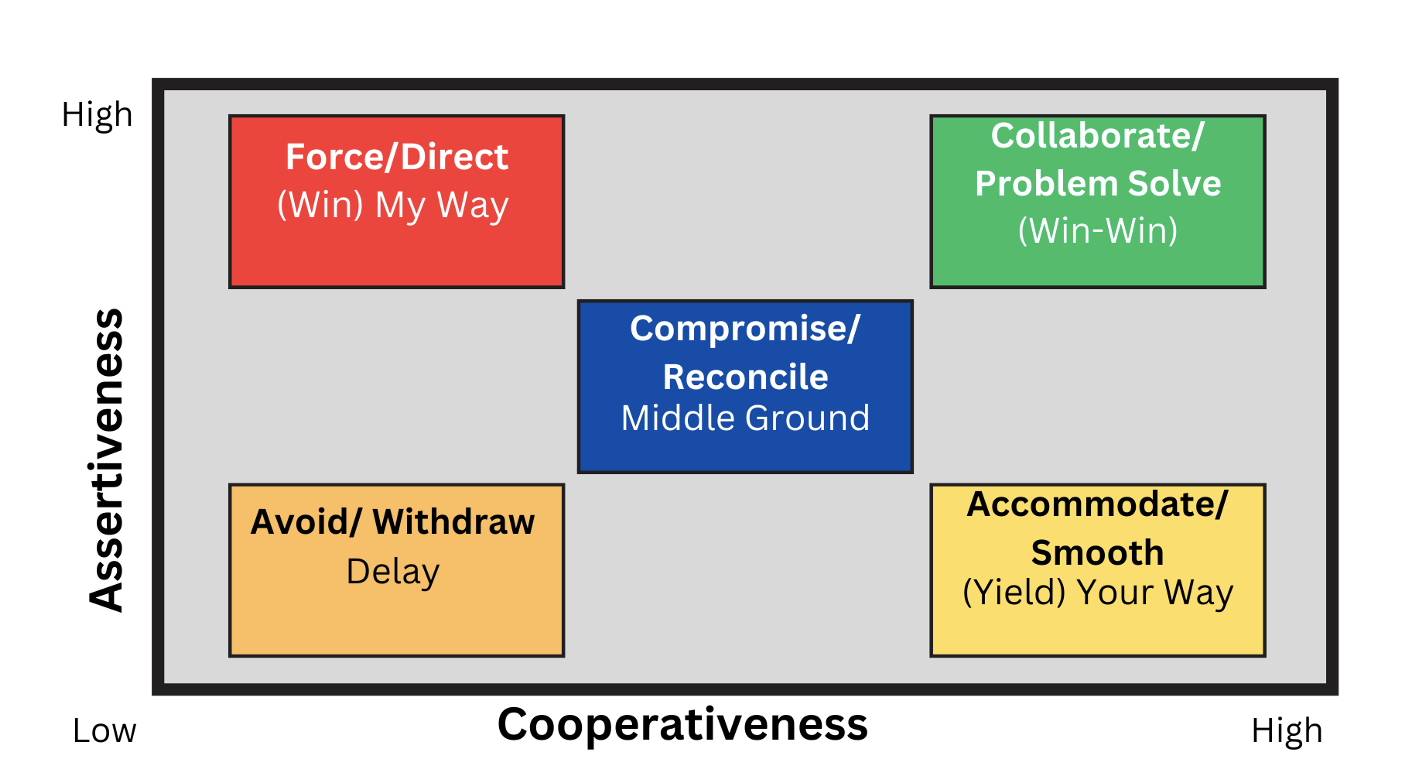

This step also has you consider the conflict-management style to which you gravitate most. The different styles of conflict resolution, according to this model, engage different levels of assertiveness and cooperativeness. The figure below shows how these five general conflict-management styles fall on the continuum of these constructs. Each technique has its own place and use. The description for each technique precedes Figure 1.

Withdraw/Avoid: This technique postpones the issue until you are better prepared to address the situation or might allow the opportunity for others to intervene if they are better suited to resolve the conflict.

Smooth/Accommodate: This technique focuses on your agreement with others instead of where your views might be different. In order to maintain the integrity of the relationship, you will concede to the solution given by others.

Compromise/Reconcile: This technique seeks to find a solution that makes others (and yourself) feel satisfied with the solution. This technique is often temporary or only partially addresses the conflict. This often ultimately leads to a lose-lose situation for all parties involved.

Force/Direct: This technique is used when you promote your views at the expense of other views. Individuals typically use this in positions of power to resolve an emergency. It is considered a win-lose approach.

Collaborate/Problem Solve: This technique evaluates several viewpoints and insights from different perspectives. This resolution requires cooperation and a spirit of collaboration, and open dialogue that results in consensus and commitment. This technique typically results in a win-win situation for all parties. This technique takes time and energy to be truly collaborative.

Figure 1 | Five Conflict Management Techniques

Note: Adapted from Thomas-Kilmann’s (1974) conflict resolution strategies and Blake and colleagues’ (1964) strategies.

Step 3—Organize the Work: Once you have established a plan, it is time to organize the entire approach. To begin the conversations and work, you should first find a set of guiding principles that establish rules, norms, policies, mission statements, values, or other starting points. These may come from a strategic plan within an organization, a company policy manual at work, or even a code of ethics/conduct or rules. If your conflict was more personal, consider your own set of values and guides within your own life to help you process the conflict. These are important because they help guide the conversation toward a set of shared guidelines.

This is also a great time to do some research on ways other organizations or parties have addressed this conflict. Their resolution may not be best for you, but it can help guide the process and help you organize what needs to be done to reach a consensus or face the conflict at hand. Taking time to plan the approach and how you will structure the conversation among all parties is also important. If you have taken the lead with the group on organizing the conversation, you want to ensure that each party gets equal time to present their facts and their side of the conflict. Decide how the conversation will flow and consider the strategies you will use to keep the discussion fresh and moving forward.

Step 4—Implement: It’s time for your planned and organized conversation. All parties are present and ready to engage in discussion. Under this step, it is important to choose a location that allows everyone to feel safe and productive. The environment is important to creating an atmosphere where others feel comfortable speaking up and sharing their perspectives. Make sure the area is free of distractions as much as possible, even if the conflict is with another family member and is happening in the kitchen. Make sure there are no loud noises (pets, traffic, technology, etc.) that will prevent the focus and listening that must occur. The next consideration is to have strategies to keep the conversation fluid and moving forward. Lucky for you, you prepared for this during Step 3. If you did not, consider probing questions that might help you and others express their perspectives or suggestions to resolve the situation or conflict.

Leader Log: Jot down some questions you might ask to guide the conversation for all groups involved. This allows you to be prepared and feel more comfortable managing conflict. Share your ideas with classmates.

Make sure you have allowed time and space for questions. Questions are how we validate the experiences and perspectives of others in order to better understand. Questions can be scattered throughout the process or might be best after all parties have presented their perspectives and potential solutions.

The decision you make to address the conflict can come from any of the techniques discussed in Step 3 or might come from another source. Decide what solution is best to resolve the conflict and close the discussion by providing the next steps for the group or individuals. Who will implement the change? Are there changes that need to be made to documents or policies in your organization? Does the conflict seem settled?

These steps offer an option for how to work through conflict. Regardless of the source of the conflict (family, friends, work, etc.), these steps can be beneficial to serve as a guide to frame your approach to finding a solution and a way to end the conflict. While the steps do not provide specific rules and ways of having the often-difficult conversations and doing the difficult work, they do provide an opportunity to approach conflict with a constructive attitude and a positive solution.

Summary

But what if, after everything has been tried, the elephant is still in the room (i.e., the conflict still persists)? Choosing a conflict management approach is contingent on the assumption that you have committed to a strategy with the best information available to you at the time. That being said, sometimes you simply won’t reach a resolution in a conflict. While a lack of resolution may be frustrating, focusing on growth and what you have learned to manage in addressing your own response to a conflict is a hallmark of self-actualization.

Remember, conflict can be healthy for organizations, teams, and individuals. It allows us to practice our listening, empathy, and other related skills. This chapter has outlined two practical ways to engage in managing conflict. There are many existing strategies to address conflict. The strategies provided by Johnson and Johnson (2017) and the steps discussed through constructive conflict (Follett, 2011; Thomas & Kilmann, 1974) can be ways to begin your conflict response. While it can be challenging to engage in approaches to resolving or managing the conflict, engaging your skills can help with this process. Emotions can often get in the way of our judgment. While this can cloud our decision-making, we must commit to resolving the challenges with solutions that make the organization, teams, other individuals, and ourselves stronger. Reflect on what you have learned and processed, and best of luck with your future elephants.

QUESTIONS FOR JOURNALING OR DISCUSSION

- Mediating a conflict is a very different role than being actively engaged within a conflict scenario. What conflict-agility (communication) strategies have you observed or used to de-escalate a conflict?

- Choose a recent conflict situation to reflect on. What were your goals? How would you describe your relationship to the other party? (i.e. not important, moderately important, very important). How did that conflict situation work out? Did you use any of the strategies discussed in the reading?

- Now, take the conflict from the previous question and describe it from the other party’s perspective. What were their goals? How would they describe their relationship to you? (i.e. not important, moderately important, very important). Which approach did they utilize in addressing the conflict? If the situation were to happen again, which of their considerations would you now consider?

- One study dealing with conflict and children used a robot artificial intelligence (AI) mediator to help settle conflicts over toys and other objects (Shen et al., 2018). Do you think AI is effective in instances like this, or does conflict management require intervention with a human element? What are your thoughts on the use of AI to resolve conflict? You can view the AI in action here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2TYjzIUnRjA.

ACTIVITIES

Case Studies in Managing Conflict

Utilizing scenarios allows for an opportunity to reflect on how one chooses to handle a conflict or about their understanding of conflict. Particularly in a student leadership situation, it is necessary to be aware of warning signs and personal biases that can influence how one responds to a conflict.

Situation 1

Four people have been assigned to your group project. You and Mohamed prefer to get started early and are done with your pieces of the project a week before the due date. The other group members, Jill and Armando, have waited until the last minute to complete their project responsibilities, which has caused tension among the group. The project is due tomorrow, and they are not yet finished with their tasks. You and Mohamed are upset and frustrated, while Jill and Armando seem to be chill, eventually completing the project at the last minute.

Discussion Questions

- What has caused the conflict?

- What approach would you use here to address the conflict?

- Within this conflict, is there an opportunity for personal and/or professional growth?

Situation 2

A Greek-letter organization has decided to plan a fun fair at a local community center. As president of the organization, you must meet with the peer officer in charge of planning the event. During your chat, you realize the fair is being organized as a fundraiser, and plans are made to charge people to attend the fair in order to raise money for the organization’s upcoming service trip. After verifying with several other officers on the team that the fair was “supposed” to be an outreach event and not a fundraiser, it is decided that you must speak with the planning chair.

Discussion Questions

- What has caused the conflict?

- What approach would you use here to address the conflict?

- Within this conflict, is there an opportunity for personal and/or professional growth?

Additional Resources

- Survival Guide for Leaders: https://hbr.org/2002/06/a-survival-guide-for-leaders

- Disagree Better: Conflict resolution insights for vital personal and business relationships from professional mediator and conflict resolution teacher Dr. Tammy Lenski. (Podcast formerly called The Space Between): https://player.fm/series/the-space-between-2359923

- Leadership Untangled Podcast, Episode 15: The Willingness to Interrogate with Dr. Jennifer Lawrence (hosted by Dr. Austin Council). This podcast focuses on controversy with civility and how to use interrogation for the purpose of understanding. Asking the question, “Do I care?” can help us frame the conversation.

S1E15: The Willingness to Interrogate with Dr. Jennifer Lawrence;

- Dare to Lead Podcast: Joy, Conflict, and Leading Creative Teams with singer-songwriter, producer, writer, and artist Kam Franklin (hosted by Dr. Brené Brown). This episode discusses what it means to lead a creative team and explains how normalizing the conflict that often occurs in the creative process is necessary to find creative magic: https://brenebrown.com/podcast/joy-conflict-and-leading-creative-teams/

REFERENCES

Blake, R. R., Mouton, J. S., Barnes, L. B., & Greiner, L. E. (1964). Breakthrough in organization development. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/1964/11/breakthrough-in-organization-development

Brügger, A., & Höchli, B. (2019). The role of attitude strength in behavioral spillover: Attitude matters—but not necessarily as a moderator. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1018. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01018

Barnhart, C. L., & Barnhart, R. K. (Eds.). (1986). Conflict. The world book dictionary. World Book Inc.

Council, A. (Executive Producer). (2021-present). The willingness to interrogate with Dr. Jennifer Lawrence [Audio podcast]. Speaker: iheart. https://www.spreaker.com/user/12832528/the-willingness-to-interrogate-with-dr-j

Deutsch, M. (1994). Constructive conflict resolution: Principles, training, and research. Journal of Social Issues, 50(1), 13-32. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1994.tb02395.x

Feirsen, R., & Weitzman, S. (2021). Constructive conflict. Educational Leadership, 78(7), 26–31.

Follett, M. P. (2011). Constructive conflict. In M. Godwin & J. H. Gittell (Eds.), Sociology of organizations: Structures and relationships, (pp. 417–427). Sage.

Heifetz, R. (1994). Leadership without easy answers. Belknap Press.

Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, T. T. (2005). Teaching students to be peacemakers (4th ed). Interaction Book Company.

Johnson, D. W., & Johnson, F. P. (2017). Joining together: Group theory and group skills (12th ed). Pearson.

Katz, D. (1965). Nationalism and strategies of international conflict resolution. In H.C. Kelman (Ed.), International behavior: A social psychological analysis, (pp. 356–390). Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Katz, N. H., Lawyer, J. W., Sweedler, M., Tokar, P., & Sossa, K. J. (2020). Communication and conflict resolution skills. Kendall Hunt Publishing.

Klimecki, O. M. (2019). The role of empathy and compassion in conflict resolution. Emotion Review, 11(4), 310-325. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073919838609

Lencioni, P. (2002). The five dysfunctions of a team: A leadership fable. Jossey-Bass.

Ma, Z., Lee, Y., & Yu, K. (2008). Ten years of conflict management studies: Themes, concepts and relationships. International Journal of Conflict Management, 19(3), 234–248. https://doi.org/10.1108/10444060810875796

Miles, R. H. (1980). Macro organizational behavior. Scott Foresman.

Shen, S., Slovak, P., & Jung, M. F. (2018, February). “Stop. I see a conflict happening.” A robot mediator for young children’s interpersonal conflict resolution. In Proceedings of the 2018 ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human-Robot Interaction (pp. 69–77).

Steen, A., & Shinkai, K. (2020). Understanding individual and gender differences in conflict resolution: A critical leadership skill. International Journal of Women’s Dermatology, 6(1), 50–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijwd.2019.06.002

Thomas, K. W., & Kilmann, R. H. (1974). The Thomas-Kilmann conflict mode instrument. Xicom.

Tjosvold, D. (1991). The conflict-positive organization: Stimulate diversity and create unity. Addison-Welsey.