Main Body

3 Defining my Vision & Setting Personal Goals

Personal Leadership Philosophy - Part 1

L.J. McElravy

The Visioning Process

Often, when we think about great leaders, we think about the change they strived to achieve. For example, Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation declared “that all persons held as slaves … are, and henceforward shall be free” (National Archives, 2022). Although the proclamation was limited to ending slavery in the rebellious states and left the inhumane practice of slavery untouched for other parts of the United States, President Lincoln communicated his vision, an expansion of freedom to many more people within the United States. Like optical vision using glasses, a vision is a tool for creating focus and clarifying what you would like to see. A vision helps focus attention on what we believe the desired future should be (Den Hartog & Verburg, 1997).

Photo by David Travis on Unsplash

INTRODUCTION

Visioning happens at many different levels. For example, organizations and teams may have a vision. In these cases, groups of people may come together to determine their collective or shared vision, articulating who and what they want to be as a group. For the purpose of this chapter, we focus specifically on visioning as an individual, or the vision people may have for themselves and for their own leadership.

Creating a vision requires us to be rooted in our past, think about the desired future, and consider how what is going on in our life today has merit and meaning (Friedman, 2008). Friedman (2008) discusses how visioning represents who you are and what you stand for and can pave the path for future success in our career and personal lives. Visioning is a process of taking thoughts and ideas and making them tangible through writing. Though a vision is future-oriented, it is based in understanding past experiences, and an important element of making sense of the past is to intentionally reflect on those experiences. In other words, to know where we want to go, we have to know where we have been and who we are.

In this chapter, you will create a vision for your leadership, referred to as a Personal Leadership Philosophy (PLP). A PLP is an individual’s vision for the kind of leader that they want to be. By elucidating your leadership vision, you are creating a beacon to serve as your guide for effective leadership. Like any visioning process, we start with self-reflection. Self-reflection, intentionally thinking about past experiences, allows us to make sense of the past in order to plan for the future. In this chapter, you will be encouraged to reflect on your leadership assumptions, beliefs, and values to help clarify a vision for your own leadership.

CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to…

- describe the relationship between leadership assumptions, beliefs, values, vision, personal leadership philosophy, goals, and behaviors.

- identify personal leadership assumptions, beliefs, and values through reflection.

- create a draft personal leadership philosophy.

- describe approach and mastery goals.

- define hope as it relates to goal setting.

- apply SMART goal format to create goals supporting personal leadership and interpersonal skill development.

KEYWORDS: Vision, personal leadership philosophy, goal setting

Visioning: Your Personal Leadership Philosophy

As a vision for your own leadership, a Personal Leadership Philosophy (PLP), can provide direction and motivation. In other words, a PLP can guide actions, behaviors, and thoughts to help you become the leader you want to be. We will provide a process to help you create a PLP, and this process will involve reflecting on your experiences to articulate your leadership values, beliefs, and assumptions.

To begin the PLP writing process, we start with a short activity. In this activity, you are given two story prompts. For each prompt, please take four to five minutes to create a story about someone described in the prompt. There are no right or wrong stories. Please make sure the story is clear in your mind (it may be helpful to write it down). You should highlight specific notes, draw a picture, or do anything that can help you create a clear picture in your mind. Within the story, please make sure you are thinking about how your character interacts with other people in the story. What are the people in the story doing, saying, thinking, and feeling? Each box below contains a specific prompt and a space for you to make notes about your story. After each prompt, there is a series of questions about the character in the story. Please refrain from looking at the questions until after the story about the character is clear in your mind. Please take about five to 10 minutes to respond to the questions.

Story #1: Someone is elected president of a student organization, and they are giving a speech to the organization after learning they won. (Please take four to five minutes to create a story about the president using the prompt above. There are no right or wrong stories. Please make sure you are thinking about how your character interacts with other people in the story. What are the people in the story doing, saying, thinking, and feeling? Please make sure the story is clear in your mind, and feel free to use the space below to take notes, draw, doodle, or whatever helps clarify the story in your mind).

Question #1: What did the president say?

Question #2: How were people reacting to what the president was saying?

Question #3: What did the president do to get elected? This may have been something said directly or something implied.

Question #4: What were the president’s priorities? This may have been something said directly or something implied.

Story #2: There is a conflict within a team working on a project. One of the members is working to manage the conflict. (Please take four to five minutes to create a story about the team member working to manage the conflict using the prompt above. There are no right or wrong stories. Please make sure you are thinking about how your character interacts with other people in the story.. What are the people in the story doing, saying, thinking, and feeling Please make sure the story is clear in your mind, and feel free to use the space below to take notes, draw, doodle, or whatever helps clarify the story in your mind).

Question #1: What did the team member say to manage the conflict?

Question #2: How did the team respond to the team member trying to manage the conflict?

Question #3: What were the priorities of the team member trying to manage the conflict? This may have been something said directly or something implied.

Now that you have finished with the stories and the questions, let’s discuss why this kind of reflection is important for a PLP.

Leadership Assumptions

Leadership assumptions are the ideas we have about what leadership “is” or “should be” that are not often part of our conscious thinking. For example, if you are appointed the president of a student organization, what would you start doing automatically? Perhaps you would want to make sure you meet everyone else in the organization. Perhaps you would read the bylaws of the organization to make sure you understand all the policies. Our assumptions are automatic thoughts about leadership. The stories provided you an opportunity to think about your automatic ideas about what leaders do, either in a specific role as president or in an informal role as a team member. To help you reflect and explore your leadership assumptions, take up to 10 minutes to brainstorm up to 25 characteristics that you think were displayed by the leaders in your stories.

Think of this process in relation to a map. The stories allowed your brain to wander; you did not know where you were going; you just kept the story moving along in any direction. Identifying the leadership characteristics is like seeing where you wandered on a map. Mapping the characteristics connects the actions of the characters to tangible waypoints, something specific you can describe.

Please review the stories and the answers to the questions to help you identify these leadership characteristics. These characteristics should represent what the leaders did, whether their leadership was effective or not. For example, if in your story, the team member was not able to manage the conflict, you should still list the characteristics of that team member. The characteristics may be the same for leaders in both stories, but you should also list any characteristics that were displayed by only one of the leaders in your stories. List these on a separate sheet using the following example below as a template.

| 1. | 6. | 11. | 16. | 21. |

| 2. | 7. | 12. | 17. | 22. |

| 3. | 8. | 13. | 18. | 23. |

| 4. | 9. | 14. | 19. | 24. |

| 5. | 10. | 15. | 20. | 25. |

These characteristics provide insight into your leadership assumptions – your automatic thoughts about leaders. Next, we will discuss leadership beliefs.

Leadership Beliefs

Leadership beliefs are the conscious ideas you have about what leadership “is” or “should be.” While assumptions are the automatic ideas you have, beliefs are the ideas you have when you get a chance to think and reflect. These are the ideas about leadership you intentionally choose to have. To help you identify your leadership beliefs, review the list of characteristics you identified and circle five to seven characteristics you think are most important. Please take a few minutes to identify these characteristics and list the characteristics using the example that follows.

| 1. |

| 2. |

| 3. |

| 4. |

| 5. |

| 6. |

| 7. |

These characteristics make up part of your leadership beliefs, what you believe leadership “is” or “should be.”

Now that you have identified some of your leadership assumptions and beliefs, we want to help you identify your leadership values. As you may remember from a previous chapter, values are ideas about appropriate beliefs, outcomes, and behaviors that are applied generally to numerous contexts (Lord & Brown, 2001). In other words, values are what we use to evaluate what we do, and what we see others do, to determine if those actions are appropriate or not.

Our values are often held across various situations. For example, if I value environmental sustainability, I likely hold this value in my home, at work, and in my social life. At home, I might be willing to make sure that I separate my recycling from my trash and take trips to a recycling center. I may choose to work for a company that focuses on promoting environmental sustainability. Within my social life, I might only want to eat at restaurants that serve locally sourced foods. This is one example of how individual values might hold across multiple contexts. To help you identify your own leadership values, take a few minutes to respond to the following questions:

- Who should lead and who should follow?

- How are followers engaged in leadership?

- What is the purpose of leadership?

- Can leadership be good and bad?

- Is leadership different from being a leader?

- What role does the situation or context play in leadership?

As you review your responses to the questions above, can you identify any values that may emerge from your responses? Again, values can be thought of as general “truths” about what leadership should be across different situations. You might also want to review the previous chapter where you identified your values to see if any of those also fit as leadership values. Below is a list of values related to leadership. This list is not comprehensive, and it is provided to give you an idea of some different leadership values.

| Autonomy | Egalitarianism | Humility | Materialism |

| Caring | Empathy | Inclusiveness | Novelty |

| Collectivism | Equity | Independence | Personal development |

| Connection | Faith | Individualism | Power |

| Conservatism | Family | Innovation | Rationality |

| Courage | Generativity | Integrity | Respect |

| Creativity | Harmony | Justice | Selflessness |

| Democracy | Hierarchy | Learning | Service |

| Duty | High performance | Liberalism | Tradition |

| Efficiency | Honor | Loyalty | Well-being |

Using your responses and any other general ideas about leadership, identify three to six values that you believe are important for your own leadership identity. You can choose from the list above, or you can list values you generate on your own. In either case, please provide your own personal definition for each of your values.

| Values | Definition |

| 1. | |

| 2. | |

| 3. | |

| 4. | |

| 5. | |

| 6. |

Using the reflective activities above, you have been able to identify your leadership assumptions, beliefs, and values. The next step is to put all of this together to create a personal leadership philosophy (PLP). We encourage you to take a few minutes to review your response above. We would then encourage you to take 15-30 minutes to write out a draft of your PLP. It may be helpful to give yourself time to write without any editing. Instead of deleting or editing what you have written, simply write the statement again in another way. Setting a time goal (for example, I will write for 30 minutes without stopping or editing) can be helpful as you try to get ideas out of your head and onto paper or a computer screen. After writing, take some time to edit and refine what you have written. Not everything you write needs to be in your final PLP, and you may also realize important ideas need to be added. Separating writing from editing allows you to make progress without getting stuck writing and re-writing the same sentence.

Below is an example of a Personal Leadership Philosophy. Please treat it as an example; your PLP should reflect your own vision for leadership and should be written in a way consistent with who you are and who you want to become as a leader.

Personal Leadership Philosophy Example 1

- Leadership is a process, not a position

- I strive to use my strengths within my leadership: honesty, creativity, love of learning, and teamwork

- I will ensure people are treated equitably

- I will not be a bystander, and I will speak out to make sure my voice and the voice of those with less power are heard

- I will devote time and energy to become the leader I want to be

- Relationships are the foundation of influence

- I will lead ethically and with moral courage

Personal Leadership Philosophy Example 2

- Leadership is a dynamic social influence process driving progress.

- I am committed to my core values. Core values are the driving force behind my actions and are the foundation of who I am and who I want to become. My core values include integrity, respect, creativity, action, and justice.

- o Integrity: my words and actions are aligned. I am committed to transparency in my decisions and actions.

- o Respect: I care for the well-being of others and myself. Respect includes treating people with compassion and dignity.

- o Creativity: I encourage innovation, creativity, and resourcefulness in others and in myself.

- o Action: Progress is achieved through active commitment and hard work.

- o Justice: I make decisions with thought and consideration. Because justice is not absolute, I strive to do what is right by accepting people as whole beings, with individualized experiences and beliefs.

- I search for clarity by challenging my values, while also recognizing my values are not universal.

- My influence permeates all my communication, and I take ownership of what and how I communicate.

- My leadership involves continuously developing myself and others.

Write your own draft Personal Leadership Philosophy

The Basics of Goal Setting

A vision for your leadership helps motivate your behaviors and actions, but it may also be too abstract to give you a clear path to living up to your vision. Like glasses, a vision provides clarity for everything within view. Within the field of vision, goals can be thought of as the specific object upon which we choose to focus. Goals concentrate and refine what we see so we can focus on certain elements out of the broader picture. Goals can be helpful because they can provide you with specific steps to take to achieve your leadership vision. If your PLP is a beacon representing where you want to be, your goals can be the map to help you get there.

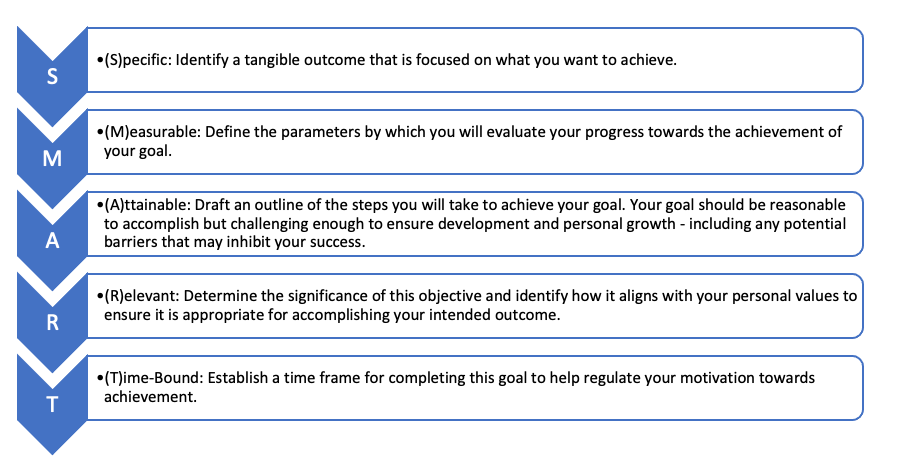

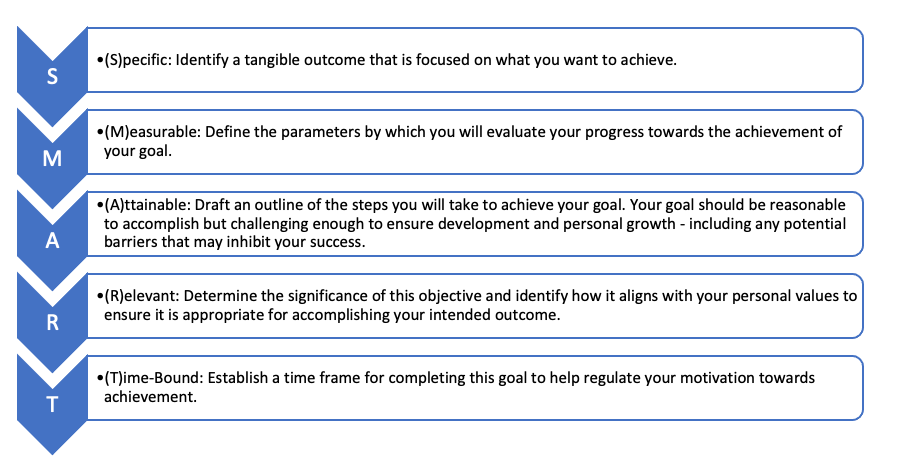

Hope is an important component of goal achievement. Although hope may seem to be an abstract idea, within the field of positive psychology, hope has a very specific meaning, and hope consists of both the willpower and waypower to accomplish goals (Ciarrochi et al., 2015; Snyder et al., 1991). Willpower is the determination to achieve goals, and waypower is the ability to generate different pathways to achieve goals. In other words, someone who has high hope will be motivated to achieve their goals, and they can find many different ways to achieve their goals. One of the best ways to develop hope is to write out goals using the “SMART” (Doran, 1981) format (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 | SMART Goals

The SMART goal format helps ensure that goals contain major components that are associated with higher goal success rates. For example, when people set specific goals vs. goals “to do my best,” people with specific goals are more likely to achieve them (Latham & Seijts, 2016). Measurable goals ensure that you can see progress and achievement. Setting specific action steps helps accomplish goals that are challenging but also attainable. Motivation is a key component of accomplishing goals, and identifying why goals are relevant helps you align motivation with goal achievement. Finally, a timeline provides urgency to a goal, supporting the need to continue working to meet the goal before the deadline.

Another factor in the success of goals is having an approach and mastery focus (Van Yperen et al., 2014). Approach-focused refers to goals where you are trying to achieve something. This is in contrast to goals where you’re trying to avoid doing something. Consider the following two goals: 1) I will spend 30 minutes editing my paper after I write it, and 2) I will avoid making mistakes in my paper. Goal one is an approach goal, and goal two is an avoidance goal. Approach goals tend to be more motivating because it is clear what defines success.

Mastery-focused refers to goals meeting a specific standard or previous performance. In contrast, a performance goal is focused on performing better than others or peers. Again, let us consider two examples: 1) I will increase my grade from a “B+” to an “A” in my course by the end of the semester, and 2) I will have the best paper in the class. Example one is focused on a specific standard, a grade, and is based on a previous performance standard of “B+,” whereas example two is using peers as the standard. Although both types of goals can lead to positive results, generally, mastery-focused goals are considered better because they promote more prosocial behavior (e.g., sharing resources with others and tolerance for opposing views) compared to performance-focused goals, which can promote more negative feelings (e.g., worry and anxiety) and unethical behaviors (e.g., cheating).

Goal Setting: Developing Leadership & Interpersonal Skills

The next step in the process of becoming the leader you envision in your PLP is to identify specific goals. That said, setting goals for your own leadership and interpersonal skill development may be different from other goals you may have set in the past. For example, setting a goal to achieve a certain grade in a class or to run a marathon have very clear, tangible outcomes. Setting goals for leadership and interpersonal skill development, such as setting goals to develop empathy or better cultural awareness, are more abstract and may require more creativity.

Where to start? This book is filled with specific skills necessary for leadership. For example, communicating with others, developing trust, and conflict resolution are some specific skills that are critical for leadership. While reviewing your PLP, take a few moments to review the skills covered in this textbook, and identify 3-5 skills you would like to focus on developing. It’s important to remember that the purpose of goal setting is to provide intentional focus, so even though all the skills in this textbook are important for leadership and are likely elements of your PLP, it’s important to prioritize a few as a starting place for your own development.

| Leadership & Interpersonal Skills |

| 1. |

| 2. |

| 3. |

| 4. |

| 5. |

Now that you have identified the skills you would like to develop, the next step is to identify how. A course project, for example, a service-learning project or group project, are great settings to work on developing your skills. To help illustrate the goal-setting process, we are going to outline interpersonal skill development within a service-learning project, where students spend 20 hours during the semester volunteering at an after-school program, where youths aged 6-12 years old attend for care between the end of the school day and when they go home (usually between 3:30 PM and 5:30 PM).

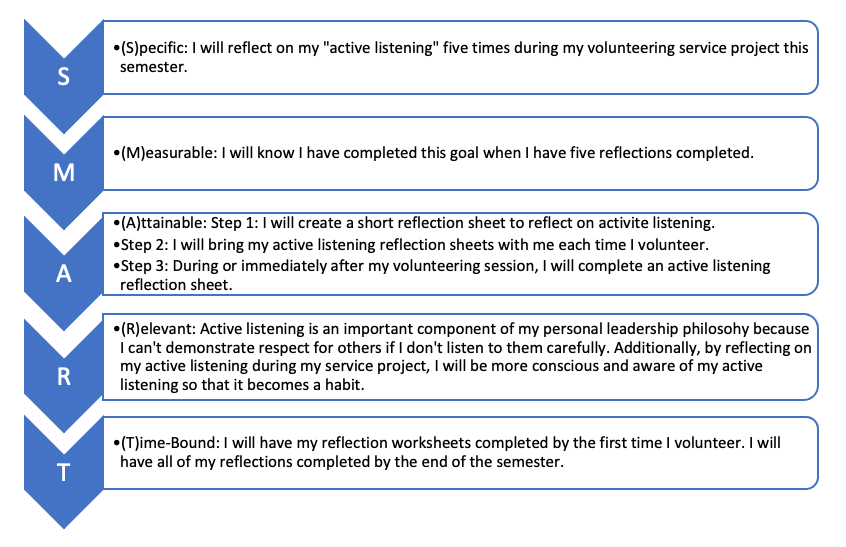

For this example, the development of active listening as a specific skill is outlined and provided in Figure 2.

Figure 2 | Active Listening SMART Goal Setting Example.

Goal Setting: Planning for Obstacles

Hope is an important component of goal success and consists of both willpower and waypower. In this section, we want to discuss waypower or visualizing multiple pathways for goal achievement. People who can visualize many ways to accomplish a goal will be able to overcome obstacles. Let’s say, for example, you want to get an “A” on your next written paper, and you intended to spend 60 minutes editing your paper. Unfortunately, you ended up with the flu, preventing you from spending the time you intended to edit your paper. Waypower is about finding many ways to achieve your goal. In this specific example, can you generate other pathways? You might be able to ask your roommate, friend, or parent to edit your paper. Additionally, you could try to rearrange your schedule so that you could free up time before your paper is due. However, we don’t have to wait for an obstacle to occur before generating different success pathways.

A premortem (Klein, 2007) is an activity that can be applied to any type of project. In short, a premortem asks people to begin by assuming their project has failed and has them generate all the reasons why the project failed. This activity encourages thinking about potential obstacles that could prevent the project from success before it begins. By identifying obstacles, you can start proactively identifying pathways and resources to overcome those obstacles. A premortem activity is a way that you can build resilience, which is known as a way to bounce back to normal or even beyond normality when faced with challenges and adversity (McElravy et al., 2018). As you set your goals for your own leadership development, it can be helpful to identify the obstacles you might face and then plan for how you might overcome those obstacles.

Chapter Summary

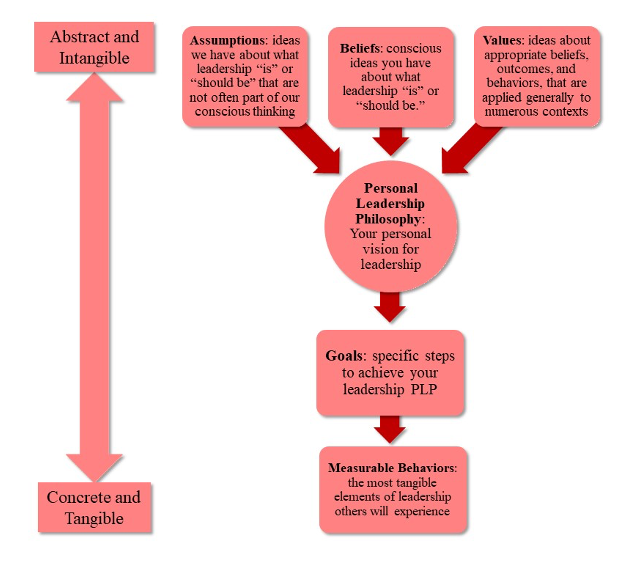

To provide an overview of this chapter, Figure 3 illustrates how the PLP and goals fit together on a scale of abstract and intangible to concrete and tangible. The reality is that our assumptions, beliefs, and values may not always be clear to us or something we can immediately identify; nonetheless, they are foundational to our leadership actions. Taking these abstract ideas and creating a personal leadership philosophy provides an opportunity for more intentionality, where we can actively choose to be a certain type of leader. As we think about how to become the leader we envision, goals provide specificity on prioritizing skill development. We can’t develop all skills at once, and goals help clarify priority and progress. Finally, the specific behaviors we display are the most tangible elements of leadership others will experience. This process of bringing the abstract to the concrete creates clarity to our own leadership development.

Figure 3 | Personal Leadership Philosophy and Goals

ACTIVITY

Exercises

Goal Setting for Your Service-Learning Project

Now that you understand the fundamentals of goal setting, use the following diagram to outline three to five S.M.A.R.T. goals that help you live out your PLP, and use your service-learning project as the context or lab to develop this skill set. Be sure to include all elements of the model in your goals.

| Goals | (S)pecific | (M)easurable | (A)ttainable | (R)elevant | (T)ime-Bound |

| Goal 1

|

|

||||

| Goal 2

|

|

||||

| Goal 3

|

|

||||

| Goal 4

|

|

||||

| Goal 5

|

|

REFERENCES

Den Hartog, D. N., & Verburg, R. M. (1997). Charisma and rhetoric: Communicative techniques of international business leaders. The Leadership Quarterly, 8, 355–391. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1048-9843(97)90020-5

Ciarrochi, J., Parker, P., Kashdan, T. B., Heaven, P. C. L., & Barkus, E. (2015). Hope and emotional well-being: A six-year study to distinguish antecedents, correlates, and consequences. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 10(6), 520–532. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2015.1015154

Doran, G. T. (1981). There’s a S.M.A.R.T. way to write management’s goals and objectives. Management Review, 70(11), 35–36. https://community.mis.temple.edu/mis0855002fall2015/files/2015/10/S.M.A.R.T-Way-Management-Review.pdf

Friedman, S. (2008). Define your personal leadership vision. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2008/08/title

Klein, G. (2007). Performing a project premortem. Harvard Business Review, 85(9), 18–19. https://hbr.org/2007/09/performing-a-project-premortem

Latham, G. P., & Seijts, G. H. (2016). Distinguished scholar invited essay: Similarities and differences among performance, behavioral, and learning goals. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 23(3), 225–233. https://doi.org/10.1177/1548051816641874

Lord, R. G., & Brown, D. J. (2001). Leadership, values, and subordinate self-concepts. The Leadership Quarterly, 12(2), 133–152. https://doi-org.libproxy.unl.edu/10.1016/S1048-9843(01)00072-8

McElravy, L., Matkin, G., & Hastings, L. (2017). How can service-learning prepare students for the workforce? Exploring the potential of positive psychological capital. Journal of Leadership Education, 16(3), 97–117. https://doi.org/10.12806/V16/I3/T1

National Archives. (2022, January 28). The Emancipation Proclamation. Online Exhibits. https://www.archives.gov/exhibits/featured-documents/emancipation-proclamation

Snyder, C. R., Harris, C., Anderson, J. R., Holleran, S. A., Irving, L. M., Sigmon, S. T., Yoshinobu, L., Gibb, J., Langelle, C., & Harney, P. (1991). The will and the ways: Development and validation of an individual-differences measure of hope. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60(4), 570–585. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.60.4.570

Van Yperen, N. W., Blaga, M., & Postmes, T. (2014). A meta-analysis of self-reported achievement goals and nonself-report performance across three achievement domains (work, sports, and education). PLoS ONE, 9, e93594. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0093594