Main Body

6 Developing Trust & Being Trustworthy

Hannah M. Sunderman

—Stephen Covey

INTRODUCTION

While trust is widely regarded as a critical component of healthy interpersonal relationships, the concept of “trust” can be difficult to define and describe. Some have described trust as launching yourself into the air and knowing someone will catch you, while others view trust as a tree that, once it is cut down, takes much time to regenerate. Although the analogies for trust are boundless, they emphasize one common theme: trust is necessary for relationships. In this chapter, we’ll explore the following questions: What is trust? How is it built? How is it maintained? How is it broken? And, finally, how does trust relate to our well-being and other areas of our life?

CHAPTER SPOTLIGHT

As told by Tori Pedersen, NHRI (formerly known as the Nebraska Human Resources Institute) Mentor

As a freshman in college and a new mentor in NHRI Leadership Mentoring, I was eager to jump into sharing my knowledge and experiences with my mentee. I wanted to hear all about her life as a middle schooler—her challenges and successes. Throughout my first year of mentoring Natalie, I quickly learned that strong relationships are not built overnight. Getting to know someone on a deeper level takes time, and most importantly, it takes trust.

Building trust with a person is not a one-time occurrence, it takes continual investment. As I met with Natalie each week, I made sure to pay attention to what she shared so that I could check in with her as time went on. This commitment to being fully present in our meetings was the foundation of trust that proved to Natalie I was there for her. The act of building trust can take on many forms. It was more than just listening during our meetings; it was pushing her to dig deeper into our conversations while respecting when she was not comfortable sharing. It was being vulnerable with her about my challenges, this way she saw me as relatable—a fellow human being full of flaws.

As a mentor, it was easy to want to see my mentee grow in the ways I envision. I have learned, though, that I needed to meet my mentee where she was and push her to grow, not in my image, but in her own direction. Respecting these differences and celebrating them was crucial to building a strong relationship centered around trust. Ultimately, small moments matter, such as my mentee sharing her dreams or telling me about a fight with a friend. It was easy to wish for big, life-altering conversations, but the small moments where someone chooses to be vulnerable and to trust you are the ones that make all the difference.

Learning Objectives

CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to…

- define trust.

- discover the effects of trust.

- analyze the process of building and maintaining trust.

- connect vulnerability and self-monitoring to trust.

- evaluate how trust can be broken and the subsequent effects on individuals.

KEYWORDS: Trust, vulnerability, trustworthiness, self-disclosure, self-monitoring, building trust

Defining Trust

Before we discuss the effects and processes associated with trust, let’s begin by defining it. Interpersonal trust ‘‘encompasses one’s willingness to accept vulnerability based on the expectation regarding the behavior of another party that will produce some positive outcome in the future” (Krueger & Meyer-Lindenberg, 2019, p. 92). In more simple language, trust is “choosing to risk making something you value vulnerable to another person’s actions” (Feltman, 2011, p. 7). For example, trusting that another member in a group project will fulfill their portion of the assignment by the deadline.

Distrust, on the other hand, is defined as the belief that “what is important to me is not safe with this person in this situation (or any situation)” (Feltman, 2011, p. 8). When we’re with someone we trust, we feel safe and able to be open. On the contrary, when we’re with someone we have not built trust with, we might feel a need to protect ourselves. The emotions connected to trust are care, open-handedness, and curiosity, while the feelings related to distrust are resignation, bitterness, and fear. When experiencing trust, we are prone to cooperation and collaboration, open communication, supporting others, thinking critically about our behaviors, and expecting the best from people and situations. When experiencing distrust, we are likely to be defensive, blame and shame others, judge ourselves and others, withhold information, and expect the worst from people and situations.

Choosing trust or distrust has been described as a risk assessment or a social dilemma. In other words, what is the likelihood that the other person will support or harm you, and to what extent do you make yourself vulnerable to their actions? Neuroscience supports the perspective of trust as a risk assessment. Specifically, reward networks in our brains “determine the anticipated reward for trusting another person” (Krueger & Meyer-Lindenberg, 2019, p. 94), while the salience network ties negative feelings to the risk of betrayal by another person. Our brains figure out context-based strategies for trust through the central-executive network, as well as relationship-based trustworthiness (e.g., trusting a partner) through the default-mode network. In sum, trust is not only something we feel in our relationships, but it is also something that occurs in our brains.

Discovering The Effects of Trust

Over the past half a century, trust has surfaced as a significant predictor of constructs like job satisfaction, job performance, and organizational commitment (Dirks & Ferrin, 2001; Flaherty & Pappas, 2000). At an organizational level, trust is positively related to revenue and profit (Davis et al., 2000). Looking at a younger age group, interpersonal trust has been found to significantly influence prosocial behavior among college students (Guo, 2017). Prosocial behavior is defined as actions that intend to help another person or group, such as volunteering or helping (Eisenberg & Mussen, 1989). This means that college students with more harmonious and trusting interpersonal relationships are more likely to engage in behavior such as assisting someone who needs help, sharing their knowledge/resources, or working with others to achieve a shared goal.

Outside of college, “trust is widely considered fundamental for the recovery of trauma survivors by enabling them to effectively manage conflict in relationships and establish mutually cooperative interactions” (Bell et al., 2019, p. 1042). Within the medical field, doctor-patient trust has been connected to increased patient satisfaction and compliance with medical advice, such as medication (Chandra et al., 2018). Finally, as stated by Krueger and Meyer-Lindenberg (2019), “Trust pervades nearly every social aspect of our daily lives, and its disruption is a significant factor in mental illness” (p. 92). For example, people who experience a mental illness such as schizophrenia can have a difficult time building and maintaining trust (Fett et al., 2012). As you can see, whether we’re discussing organizations, college students, or the medical field, the effects of trust are both broad and deep.

Analyzing The Process of Building and Maintaining Trust

As stated by John Gottman, a psychological researcher and clinician,

Trust is built in very small moments, which I call ‘sliding door’ moments. In any interaction, there is a possibility of connecting…or turning away…One such moment is not important, but if you’re always choosing to turn away, then trust erodes in a relationship—very gradually, very slowly. (Greater Good Science Center, 2011).

Gottman refers to small, trust-building experiences as “sliding door” moments, named after the movie Sliding Doors, which alternates between two storylines that demonstrate two different paths the main character’s life could have taken depending on whether or not she caught a train.

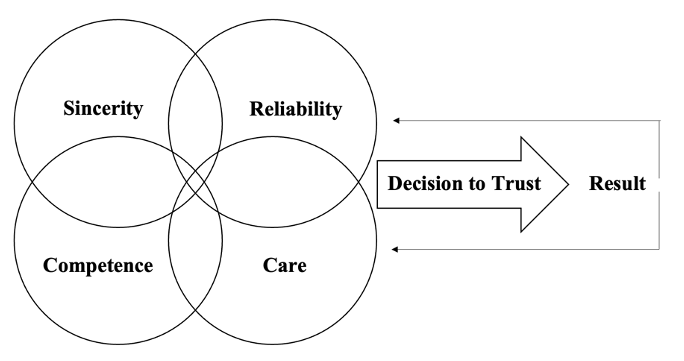

Building upon the idea that trust is built over time in small moments, Feltman (2011) shares a model in which the choice to trust is comprised of four distinct aspects of how a person might act (see Figure 1). The four aspects are as follows:

- Sincerity—the assessment that a person is honest, they are true to their word and their word is true, their opinions are valid and supported by evidence (e.g., a manager outlines the three largest obstacles facing a group and shares a two-part strategy grounded in research for overcoming them)

- Reliability—the assessment of how well a person keeps commitments (e.g., a friend says they’ll reach out to you in a week to schedule a time to get together and they do)

- Competence—the assessment that a person has the required skills, knowledge, and resources to do what they are supposed to do (e.g., a social media chairperson for a campus organization knows how to build a social media plan)

- Care—the assessment of how much a person is concerned with the interests of others as opposed to being exclusively motivated by self-interest (e.g., a friend tells you about the opportunity to apply for a competitive scholarship for which they are also applying)

Figure 1 | Model of Trust Adapted from Feltman (2011)

Collectively, these four aspects of trust lead us to either choose to trust someone or choose not to trust someone. When we choose to trust someone, we monitor the outcome, asking ourselves questions such as, “Were the results positive? Did they honor our trust?” If the answer to these questions is “yes,” our assessment of the other individual continues to grow, and we view them as more sincere, more reliable, more competent, and/or more caring.

Closely connected to building trust is the concept of vulnerability. Vulnerability is defined as risk uncertainty or emotional exposure (Brown, 2015). To use a previous metaphor, if vulnerability is launching yourself into the air, trust is knowing someone will catch you. Trust fuels our vulnerability, and vulnerability fuels our trust. In other words, vulnerability is critical to building trust (as evidenced by the definition of trust we discussed previously). We must be honest with others for them to know we are sincere and that we care. Likewise, trust allows us to be vulnerable. Having an idea that someone will respond to our vulnerability with kindness (i.e., a positive outcome) provides us with the sense of safety and security required to self-disclose. As such, trust and vulnerability are iterative processes, building upon each other to foster strong relationships. As trust builds in an interpersonal relationship, so does our willingness to be vulnerable. As vulnerability occurs in our interpersonal relationships, trust builds.

How Trust Can Be Broken

While trust is critical to interpersonal relationships, it can also be difficult to maintain. Most of us could likely think of an experience where we lost trust in a friend, family member, or co-worker. Research has revealed that interpersonal trust is most often lost “when the trusted individual lied or did not follow through with what they were expected to do” (Hupcey & Miller, 2006, p. 1136). While a few participants in the research study described a situation in which trust has been lost all at once (e.g., a partner who has an affair), the majority of participants shared that interpersonal trust was lost slowly over time (e.g., friend not listening to you, ignoring your texts, etc.). In other words, trust is like a brick wall. We build interpersonal trust by gradually adding bricks. Likewise, we most frequently lose trust by taking apart the wall brick-by-brick. Once in a while, the loss of trust occurs more like a wrecking ball slamming against the wall and scattering many bricks at once.

When we experience a loss of trust, some individuals believe that trust cannot be rebuilt; however, the majority of people believe trust can be rebuilt through a slow and long process (Hupcey & Miller, 2006). When trust is lost, the first step is a sincere apology in which a person does the following (Lewicki et al., 2016):

- Expresses regret

- Explains what went wrong

- Takes responsibility

- Declares remorse

- Shares how they will make it right

- Asks for forgiveness

After a sincere apology, trust may be rebuilt through the intentional and consistent implementation of the four aspects of trust: sincerity, reliability, competence, and care (see Figure 1; Flaherty & Pappas, 2000).

Notably, a loss of trust in one relationship impacts other relationships. For example, individuals who are victims of interpersonal trauma, defined as a traumatic experience caused deliberately by another person (e.g., emotional neglect), are twice as likely to develop post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) when compared to individuals who experience accidental trauma (e.g., a natural disaster) (Charuvastra & Cloitre, 2008), emphasizing the critical role interpersonal trust plays in our lives.

Connecting Trust to the Social Change Model

Commitment, a value of the Social Change Model (SCM), is the goal-directed investment of time and energy into the process of leadership development (Higher Education Research Institute, 1996). Likewise, trust often requires an investment of time and energy. The two concepts, commitment and trust, are inextricably linked. As described by the Higher Education Research Institute (1996), “Commitment goes hand in hand with trustworthiness. Trust involves a certain amount of risk since it takes some degree of initial trust to join with others… That initial trust can be sustained only through commitment, and commitment is strengthened in turn as trust is established and common purpose is defined” (p. 43). Trust in our interpersonal relationships is necessary for building committed groups and teams that can achieve meaningful change.

In sum, trust is necessary for interpersonal relationships. When we choose or experience trust, we experience care, open-handedness, and curiosity; however, when we choose or experience distrust, we experience resignation, bitterness, and fear. We can build trust over time by being sincere, reliable, competent, and showing care (Flaherty & Pappas, 2000). Consider how you might use what we discussed throughout the current chapter to improve trust in your own relationships by processing how you build relationships with friends, family members, classmates, and coworkers.

QUESTIONS FOR JOURNALING OR DISCUSSION

- Reflect on a trusting relationship in your own life and chart the development of trust over time. When did it start? How did it grow? What were the high points? When did it “dip,” and how did it recover from the “dips”? Where might trust in this relationship go from here (i.e., how can it keep growing)? How can you apply what you’ve learned from this relationship to other relationships?

- Reflect on a current or past relationship in which trust was fractured, and chart the change in trust over time. Why was trust broken? Did it happen slowly over time or was it one main moment? What emotions accompanied the fracture of trust? How has it affected you, this relationship, and your other relationships?

- Through a lens of trust and commitment, analyze a group/team of which you’ve been a member. What level of trust and commitment did this group/team possess? How were trust and commitment connected? How did trust and commitment influence the effectiveness of this group/team?

ACTIVITIES

Classroom Activity Video Exercise

Watch the following video of Dr. John Gottman explaining how trust is built – https://youtu.be/rgWnadSi91s

- Discuss the following questions: What surprised, encouraged, or challenged you in this video? How does Dr. Gottman explain “sliding door moments”? What is a “sliding door moment” from your own life (encourage students to think about their relationships with their friends or family?)

- Consider your trustworthiness. When have you been trustworthy? When have you not? How can you improve your trustworthiness?

Classroom Activity Writing Exercise

- Have students do one of the first two journaling prompts in class by graphing trust in a relationship and ask them to share in small groups. Students can share as much or as little as they want. Guide students through small group sharing with structured questions (see questions above)

Case Study on Trust

- Read the following article about the England football team: https://www.theguardian.com/football/2018/jul/10/psychology-england-football-team-change-your-life-pippa-grange

- Consider the following questions: What stood out to you in the article? How did the article demonstrate the power of trust? Based on the content of this class, what else might help the football team build trust? Consider a time when you’ve been on a team; how did your group/team compare to the England football team in terms of trust? How might your/team build a culture of trust?

REFERENCES

Bell, V., Robinson, B., Katona, C., Fett, A. K., & Shergill, S. (2019). When trust is lost: The impact of interpersonal trauma on social interactions. Psychological Medicine, 49(6), 1041–1046. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291718001800

Brown, B. (2015). Daring greatly: How the courage to be vulnerable transforms the way we live, love, parent, and lead. Penguin.

Chandra, S., Mohammadnezhad, M., & Ward, P. (2018). Trust and communication in a doctor-patient relationship: A literature review. Journal of Health Communication, 3(3), 36. https://doi.org/10.4172/2472-1654.100146

Charuvastra, A., & Cloitre, M. (2008). Social bonds and posttraumatic stress disorder. Annual Review of Psychology, 59(1), 301–328. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085650

Davis, J. H., Schoorman, F. D., Mayer, R. C., & Tan, H. (2000). The trusted general manager and business unit performance: Empirical evidence of a competitive advantage. Strategic Management Journal, 21(5), 563–576. https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1097-0266(200005)21:5<563::aid-smj99>3.0.co;2-0

Dirks, K. T., & Ferrin, D. L. (2001). The role of trust in organizational settings. Organization science, 12(4), 450–467. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.12.4.450.10640

Eisenberg, N., & Mussen, P. H. (1989). The roots of prosocial behavior in children. Cambridge University Press.

Feltman, C. (2011). The thin book of trust: An essential primer for building trust at work. Thin Book Publishing.

Fett, A. K. J., Shergill, S. S., Joyce, D. W., Riedl, A., Strobel, M., Gromann, P. M., & Krabbendam, L. (2012). To trust or not to trust: The dynamics of social interaction in psychosis. Brain, 135(3), 976–984. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awr359

Flaherty, K. E., & Pappas, J. M. (2000). The role of trust in salesperson—sales manager relationships. Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 20(4), 271–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/08853134.2000.10754247

Greater Good Science Center. (2011). John Gottman: How to build trust [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rgWnadSi91s

Guo, Y. (2017). The influence of social support on the prosocial behavior of college students: The mediating effect based on interpersonal trust. English Language Teaching, 10(12), 158–163. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v10n12p158

Higher Education Research Institute. (1996). A Social Change Model of Leadership Development (Version III). UCLA. https://www.heri.ucla.edu/PDFs/pubs/ASocialChangeModelofLeadershipDevelopment.pdf

Hupcey, J. E., & Miller, J. (2006). Community dwelling adults’ perception of interpersonal trust vs. trust in health care providers. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 15(9), 1132–1139. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2006.01386.x

Krueger, F., & Meyer-Lindenberg, A. (2019). Toward a model of interpersonal trust drawn from neuroscience, psychology, and economics. Trends in neurosciences, 42(2), 92–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tins.2018.10.004

Lewicki, R. J., Polin, B., & Lount, R. B. (2016). An Exploration of the Structure of Effective Apologies. Negotiation and Conflict Management Research, 9(2), 177–196. https://doi.org/10.1111/ncmr.12073