Main Body

8 Diversity & Inclusion

Gina S. Matkin & Helen Abdali Soosan Fagan

INTRODUCTION

In the Social Change Model of Leadership, Collaboration is defined as “Working with others in a common effort by capitalizing on varying perspectives and the power of diversity” (see Table 1 in the Introduction Chapter). This group-level value in the SCM model is essential if we want to work toward common goals in a way that values all voices.

Diversity and inclusion have never been more important or talked about issues than they are today. With the connectedness of our world via social media, video conferencing, news outlets, and other sources, we instantly hear what is happening the moment it occurs. This kind of connectedness requires a new lens through which to view our world and consider how our own identity plays a role in our perceptions of it. Additionally, as our world becomes more complex and connected, we need new ways to look at and talk about the world in less divisive and more inclusive ways.

This chapter will lead us on a journey to consider who we are at the many levels of our identity, how we can come from a place of knowing ourselves to better seeing and understanding others, and how we can challenge ourselves to shift our perspectives to see differences in a new and more holistic way to create more inclusive environments that welcome and value everyone!

CHAPTER OBJECTIVES:

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to…

- define diversity and explain its application to your own identity.

- define inclusion and explain its application to your own identity.

- describe the various parts of your own identity and how you experience them as either advantaging or disadvantaging you.

- apply your understanding of diversity and inclusion as they relate to you as an emerging leader in fostering collaboration and leading a diverse group or team to a common purpose.

KEYWORDS: Diversity, inclusion, identity, inclusive leadership, privilege, marginalization

It is easy to look at the world through our own lens and draw conclusions based on who we are and what we have experienced. This chapter challenges us to go beyond the “known” and into a more challenging territory where we seek to see the world, not as we are but as it is.

This may sound simple to do, but it requires us to both listen openly and be willing to learn from those around us. We often tell our students that there are two important things to remember when engaging in discussions where we might have a different opinion or perspective:

- Listening to you does not mean I agree.

- Learning from you does not mean I will change my mind…but I might.

Students tell us that these two statements, when taken to heart, open up a kind of spaciousness in the room where assumptions can fall away, and we can really hear each other. Often our judgment or reaction to others who are different from us is based on fear. It might be fear of what others will think if I listen and do not openly disagree. It might be protecting a value that I hold dear. Either way, if we face our fear or discomfort, there is so much to learn!

This chapter on diversity and inclusion focuses on helping us see differences in a more holistic and positive way. We present you with ways to consider and welcome difference. This starts by examining who you are. We believe the only true way to value differences in others is to be completely open and comfortable with who you are! Being authentically “you” actually helps others be more authentically who they are when they are with you. This also includes the recognition that who we are may offer some advantages (often termed “privilege”) or disadvantages (sometimes called “marginalization”) depending on where we are and who we are surrounded by. Being aware of both our privileges and where we may be marginalized may help us be more skilled at creating spaces where others feel both welcomed and truly seen!

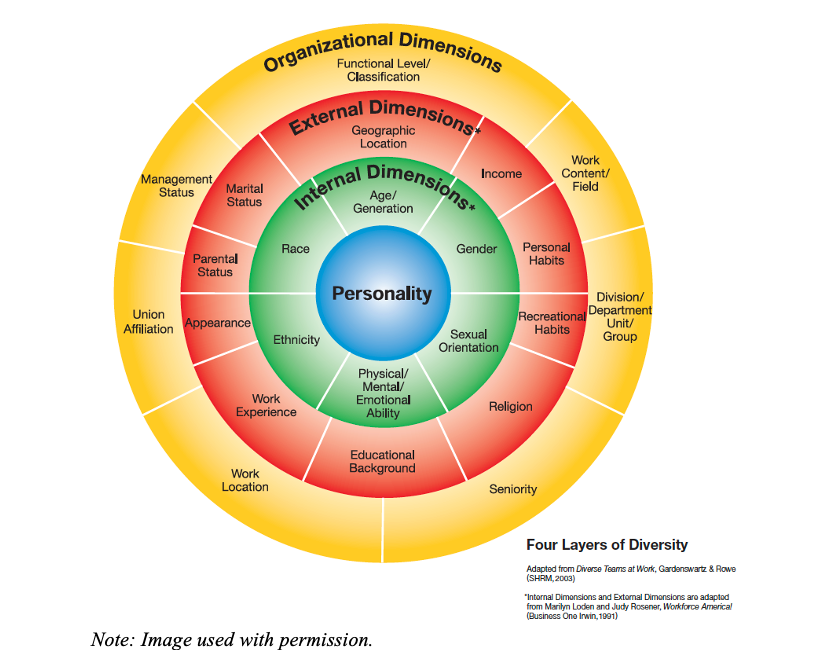

The Four-Layer Model of Diversity

The first model we want to introduce you to is the Four-Layer Model of Diversity. Think about the last time you heard the term “diversity.” What was the setting? What did you think was meant by this term? We define diversity as simply the “mix of differences.” Often we think of these differences as those you can observe, but there is much more to diversity and our “mix of differences” than meets the eye. Diverse Teams at Work (Gardenswartz & Rowe, 2003) depicts diversity by looking at both the internal and external dimensions. This model, originally presented by Marilyn Loden and Judy Rosener (1991) in their book, Workforce America, illustrates diversity as far beyond what we can observe. This model helps us to see the numerous dimensions in which human beings are different. Diversity is the reality that those differences exist between us. Put quite simply, diversity is the many ways human beings are similar and different. These differences become the layers through which we experience the world, and the world experiences us (see Figure 1). While it is evident that human beings are similar and different in many ways, all differences are not equal. We cannot deny the fact that race, ethnicity, gender, age, and sexual orientation are topics that have been challenging humanity for centuries.

Figure 1 | The Four Layers of Diversity

At the core (blue) is personality. This core drives much of the connection we sense when we first begin to interact with people who think like us, process information like us, and manage their lives like us. This layer is the beginning of and often the most overlooked layer of diversity.

The next level (green) depicts the internal dimensions considered by Gardenswartz and Rowe (2003) as “powerful shapers of opportunities, access, and expectations” (p.32). These move our understanding of diversity beyond the central core of personality to the six internal dimensions of diversity that, for the most part, we do not choose or control, yet they have a powerful effect on our behavior, attitudes, and opportunities in organizations and communities. Briefly described, these six dimensions are:

- Age – generational differences between us drive our expectations of work, family, life, loyalty, security, etc. Diving into age differences helps us to understand that not all people have the same perspectives. It also helps us understand that while age certainly helps shape our perspective, it does not confine us to a particular way of thinking.

- Gender – While the authors were referring to biological sex when they created this model, the word sex and gender continue to be confused and used synonymously by many. While helping you understand the differences between sex and gender is beyond the scope of this chapter, it is important to recognize that differences exist and that conforming or not conforming to gender norms societally prescribed by one’s sex has become an important topic in diversity and inclusion discussions.

- Race – Contrary to popular belief, we do not live in a color-blind society, nor should it be our goal. Human differences, often focused solely on the color of one’s skin, have continued to limit human beings’ appreciation of differences. The term race began to be used during colonization and expanded with each century since then. Race is described as a social construct used to categorize visual differences in the color of skin, slant and roundness of eyes, the width of the nose, texture of hair, etc. (See this 2021 article from Braverman and Dominguez in Frontiers in Public Health for an in-depth look at this: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8452910/pdf/fpubh-09-689462.pdf).

- Ethnicity – Differences connected to one’s ancestral origins (national and/or tribal) are the differences that make up the differences in ethnicity. Often people confuse ethnicity and race. Differences in ethnicity often lead to differences in language, celebrations, and what is considered “cultural”; however, culture is broader than ethnicity. Culture is made up of beliefs, behaviors, attitudes, and expectations that humans consider “normal” in assessing others. Culture begins to take shape in a family, which is operating in the confines of a nation. While national and ethnic cultures are generally the place we begin to think about culture, they are not the only layers of culture.

- Physical/Mental/Emotional Abilities – Physical, mental, and emotional abilities differ between human beings. While the original model focused on physical abilities, for the purposes of our conversation, we will think of abilities in a much broader way to include physical and cognitive abilities, as well as neurodivergence.

- Sexual Orientation – Humans differ widely when it comes to sexual orientation, and that has continued to expand over the past decade. The key factor is that not all humans are heterosexual and if people judge each other based on sexual orientation, it erodes trust and teamwork, and does not allow open authenticity in identities to emerge.

Identity Activity: Let’s make this personal!

Consider this:

- What aspects of your internal dimensions of identity (age, race, gender, sexual orientation, etc.) do you most identify with?

- Are there any aspects of identity that you do not feel safe/comfortable revealing or discussing in some situations or settings? Why?

Take a moment to list as many answers to the question, “Who am I?” as come to mind in 2–3 minutes (even beyond the internal dimensions). Notice what you put on the list and what might be missing (what did you not think of right away). Now ask yourself if you would have created the same list if you were asked to share it publicly in a group, class, family setting, etc. If the lists would be different, why?

As you look back over these lists, consider the parts of your identity that you feel benefit you in some way and those that might create challenges or even barriers (judgment, misperceptions, assumptions, etc.).

Now consider situations when you have been more aware (or less aware) of these benefits and challenges. How do you think others experience their own identities and navigate those? Considering your own and then others’ identities and experiences can go a long way toward greater understanding and empathy.

There are two additional layers to this model: the external layer of differences, which includes things such as income level (socioeconomic status), religion, appearance, etc., and the organizational layer of differences, which includes work field, seniority, etc. In this chapter, we are mainly focused on the internal dimensions, but you can easily see how these additional layers add complexity to our identity and how we experience it.

In learning about the four-layer model of diversity, we can see that human beings are all very complex and that we all belong in the discussions around diversity. Diversity is not about only one group. It is about all human beings. In fact, we all possess a multitude of identities based on race, gender, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, physical/mental/emotional abilities, etc. We are not just one thing. This concept can be better understood by exploring the term “intersectionality.” While a conversation about intersectionality is beyond the scope of this chapter, you can learn more about what it means and find some additional resources at this website (Flowers, 2019): https://www.edi.nih.gov/blog/communities/intersectionality-part-one-intersectionality-defined

How we navigate the differences is what helps us succeed or fail at feeling a part of the world around us while still feeling free to be who we truly are. We term this “inclusion.” We will learn more about this in the section that follows.

Inclusion: It’s More Than You Think

You may have heard talk of “inclusion” or “inclusive leadership” recently. This term does not replace talking about “diversity” but rather moves us to the next step. While diversity is, in essence, about the mix of differences, inclusion is about bringing differences together. It is important to note that diversity is not something that describes a single individual but rather how a group, team, workplace, or community can be diverse if people from various racial, ethnic, sexual orientation, and/or other identity groups are represented.

Inclusion is about more than just representation. Inclusion is about how we engage with each other and who has access to resources, decision-making, etc. Essentially it is about connection and voice! Is everyone included in decision-making? Does everyone feel heard and valued? Does everyone feel that they can bring ALL of who they are to the workplace, organization, classroom, or community? These are a few of the questions that we have to ask in order to gauge whether we are creating inclusive environments.

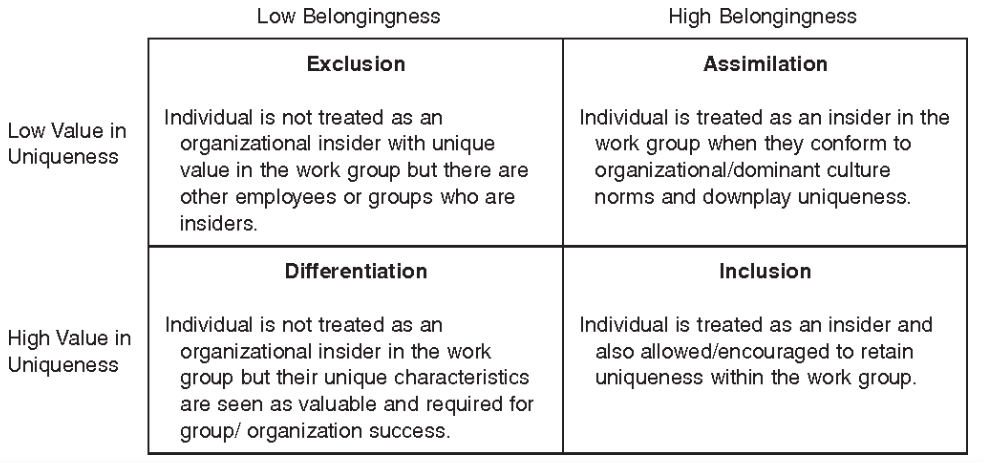

We often think that when people feel a sense of connection of belongingness, then inclusion has been achieved. This is only partly true. Belongingness is an important component of inclusion, but it does not tell the whole story.

Lynn Shore and colleagues (2011) developed a model to help us understand inclusion in a more holistic way. This model is based on two needs that humans have: the need for belongingness and the need for uniqueness (Brewer, 1991). Shore and colleagues used this concept to create a guide for a better understanding of how inclusion works. Shore’s model identifies the two needs and explains what a person might experience based on the presence, absence, or lack of balance in both belongingness and uniqueness (See Figure 2).

Figure 2 | Shore et al., Inclusion Framework (2011)

For example, if a person is feeling that they do not belong and that their unique characteristics are not seen or valued, they experience “exclusion.” Conversely, if a person feels a sense of belongingness AND also feels that their uniqueness is valued and encouraged, they experience “inclusion.” It is important to note that belongingness paired with the absence of valuing uniqueness or individuality can create an environment of “assimilation” where a person feels they must conform to the group norms in order to continue to be accepted. This is what the authors of this chapter call a “false sense of inclusion.” Finally, if a person feels that they are valued for what they can contribute or bring that is unique but that they are not really accepted, it can lead to “differentiation,” where the person ultimately feels used for their skills and talents but not seen as a member of the group or team.

This model offers an important contribution in helping us to see that inclusion and inclusive environments go beyond belongingness and require something much more complex. As a leader, your team or group will be much stronger if you carefully consider both belonging and uniqueness.

Building on Shore et al.’s (2011) model, Fagan et al. (2022) conducted an extensive review to determine how leaders create inclusion for followers. From this review, a list of seven “attributes” of inclusive leaders emerged. These were:

- Authentic Leadership

- Changemaker

- Collaborative

- Commitment to diversity and cultural competence

- Ideals

- Offering follower support

- Openness

When the seven attributes are acted upon, leaders are able to have impacts on followers that create more inclusive environments. It should be noted that the mix of these attributes is important as some may foster belongingness while not encouraging uniqueness. They state,

We believe that while some impacts may relate more toward belongingness instead of uniqueness—such as increased organizational commitment—and are beneficial for overall inclusion, inclusive leaders should be able to recognize the impacts they create as relating to both uniqueness and belongingness. (Fagan, et al., 2022, p. 101)

This observation is important in that it may feel good to help another person connect and feel as if they belong; however, if a person feels they have to conform and cannot be themselves, they will not experience true inclusion.

Scenario 1

Halle was hired by Brave Marketing company. She was the best candidate because of several successful campaigns with a rapper who was expanding his reach into clothing. Halle is the only female and the youngest person on this team. While she has been told her work is great, every time the team gets together after work, they don’t include her. And during side conversations, she is not engaged by other team members, and when she tries to engage with them, they shy away from her. Her unique talents are appreciated, yet she still feels like she made the wrong decision in joining this marketing firm because she really doesn’t feel like she belongs.

Do you think Halle feels valued for her contributions to the team?

Do you think she feels she is accepted as a member of the team?

Is Halle experiencing true Inclusion? If not, what is missing, and what could the team do differently to truly help her feel included?

We can begin to notice in ourselves and in our groups, classes, and other environments when inclusion is happening and when it is not. At times, noticing may be all you do, as it may or may not feel safe to intervene or ask for support. At other times, you may be able to advocate for yourself or others to make sure your group is being truly inclusive.

Reflection

Have you ever been in a group where you felt that you had to adapt to the norms of the group in order to be liked or accepted? If so, you have been experiencing an “assimilation environment.” This environment keeps us from being able to bring our full selves and our unique perspectives and ideas to the group. It essentially “silences” the person who feels they must conform in order to be accepted. Ask yourself how this would make you feel and whether you would want to continue to be part of the group if you experienced this “silencing.”

As you grow and develop in your awareness, you may find that you develop the skills and comfort level to help make the groups and other environments in which you live and work become more inclusive.

Scenario 2

Claire recently completed a class in diversity that was part of her leadership minor. Before the class, she had never thought of herself as a person who is uniquely positioned to bridge differences because she is biracial and her parents are from two different countries. During the class she gained a level of self-awareness, but was still trying to figure out what that meant for her.

Recently, during a conversation with her roommates about Disney movies, the topic of a black Ariel came up. Her roommates, who are both white, felt that having a black Ariel ruined the movie for them, and stole their childhood memories of being a mermaid. Claire could feel herself getting sad, and yet found herself unable to speak up. Claire was thinking, what about the millions of little black girls who also dreamed of being a mermaid? It sure would have been nice to have that when she was their age.

Part of the challenge of being biracial was that so many people around her made her feel like she didn’t fit in. She wasn’t black enough to be with the black kids, and she wasn’t white enough to be with the white kids. When she was with her cousins on her mom’s side, she stood out because of her skin color. When she was with her cousins on her dad’s side, she stood out because of her skin color.

Now, with her roommates, she had at least found a bond over time. She wanted to scream at her roommates to try to help them see how their words were making her feel. She felt bad for even thinking that way and didn’t know how to share her thoughts, so she just listened and nodded. She wanted to help them understand but didn’t want to seem too different.

- What is Claire experiencing with her roommates? Do you think she feels that her uniqueness is recognized and valued?

- How might the roommates have approached the conversation differently to make sure that all voices felt comfortable expressing their views?

QUESTIONS FOR JOURNALING OR DISCUSSION

How do I feel when I am not fully included in a group but want to be?

- What is it like to feel like I belong to a group, but not feel safe being my unique self (assimilation)?

- What is it like to feel that my uniqueness is needed to accomplish something but that, otherwise, I do not really feel as if I belong as a member of the group (differentiation)?

How can I, as a group member or a leader, help others feel truly included?

-

- What questions can I ask?

- How can I balance helping someone feel that they belong AND that their uniquenesses are valued as well?

Activity

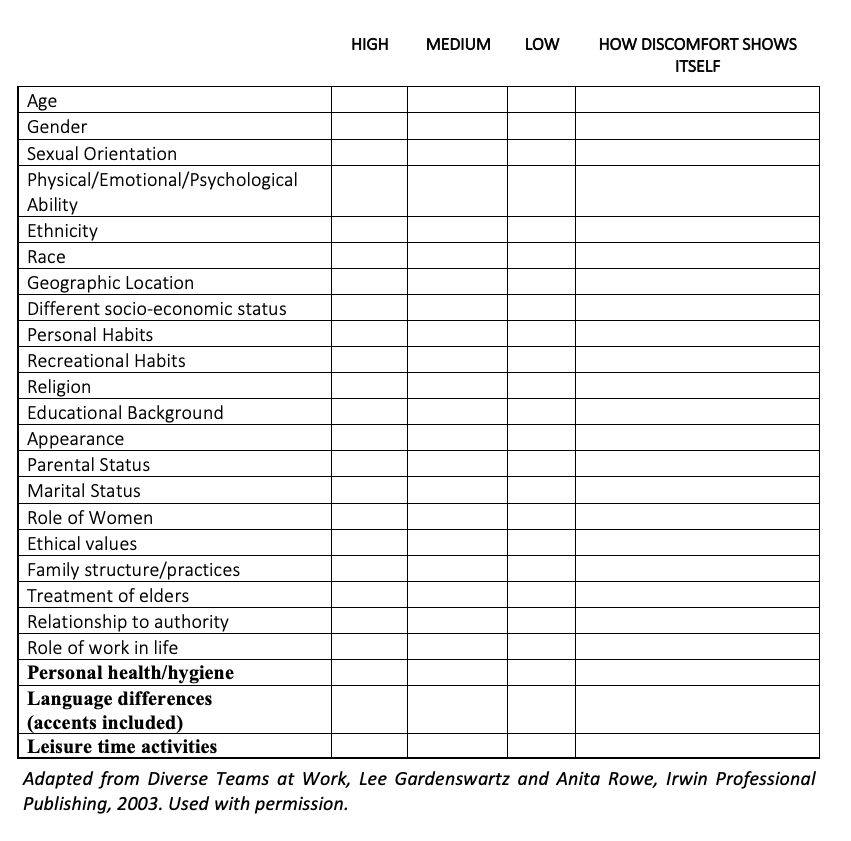

Comfort with Differences

Part 1: Assessing Your Comfort with Differences

If we pause and really reflect, we will know that we truly are more comfortable with some groups than others. Dr. Fagan sometimes likes to ask her students: “Who would you be most afraid to bring home as your future spouse?” The reason for the question is to get students to be honest about their level of comfort/discomfort with certain groups. Don’t feel bad. Everyone has varying levels of experience and comfort/discomfort. It is part of being human. The key to being effective as a leader is to be honest enough with yourself that you learn to manage it.

Directions: Think about each dimension of diversity and rate the level of comfort you feel in dealing with people different from you in that dimension.

Adapted from Diverse Teams at Work, Lee Gardenswartz and Anita Rowe, Irwin Professional Publishing, 2003. Used with permission.

Part 2: Processing Your Comfort with Differences

Objectives:

- To identify areas of personal discomfort in dealing with diversity

- To gain an understanding of what triggers that discomfort and gather ideas for becoming more comfortable

Processing the Activity:

- Your instructor might begin with a brief lecturette acknowledging the role of individual perspectives and experience in determining comfort level across various diversity dimensions.

- You will then respond to each item in the assessment with either a high, medium, or low score. Where there is low comfort, participants can write in the box “How discomfort shows itself.” Please be as honest as possible. You won’t have to share anything you are not comfortable sharing.

- The class will then discuss either in pairs or small groups. The number of participants and the level of trust influence the size of the discussion group. Where there is little trust, groups of 2 or 3 are preferable. If high trust exists, groups can be larger.

- Your instructor will give the small groups or dyads time (approximately 15 minutes) for sharing and discussion.

- After the small groups/dyads, the class will reconvene and have a large group discussion focusing on areas of greatest discomfort, reasons for that discomfort, and suggestions or ideas for becoming more comfortable. Since it is likely that different classmates will have varying levels of experience with different groups, this can be a particularly rich—and sometimes uncomfortable—discussion. Remember that the point is not to judge but to learn!

Questions for Discussion:

- Which areas have high comfort levels? Which ones have the lowest?

- To what do you attribute the differences?

- Where has the comfort level changed, either getting more or less comfortable?

- What has brought about the change?

- What is the consequence to your relationships and career opportunities if no change is made?

- What can you do to increase your comfort in places where it needs to increase?

REFERENCES

Braverman, B. & Dominguez, T. P. (2021). Abandon “race.” Focus on racism. Frontiers in Public Health, 9, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.689462

Brewer, M. B. (1991). The social self: On being the same and different at the same time. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 17(5), 475–482. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167291175001

Fagan, H., Wells, B., Guenther, S., & Matkin, G. S. (2022.) The path to inclusion: A literature review of attributes and impacts of inclusive leaders. Journal of Leadership Education, 21(1), 88–113. https://doi.org/10.12806/V21/I1/R7

Ferdman, B. M. (2018, October 25). Inclusion at work. Society of Consulting Psychology. https://scpd1.memberclicks.net/index.php?option=com_dailyplanetblog&view=entry&category=main-blog&id=25:inclusion-at-work

Flowers, H. (2019). Intersectionality part one: Intersectionality defined. National Institutes of Health. https://www.edi.nih.gov/blog/communities/intersectionality-part-one-intersectionality-defined

Gardenswartz, L., & Rowe, A. (2003). Diverse Teams at Work: Capitalizing on the power of diversity. Society for Human Resources Management.

Loden, M., & Rosener, J. B. (1991). Workforce America!: Managing employee diversity as a vital resource. Business One Irwin.

Shore, L. M., Randel, A. E., Chung, B. G., Dean, M. A., Ehrhart, K. H., & Singh, G. (2011). Inclusion and diversity in work groups: A review and model for future research. Journal of Management, 37(4), 1262–1289. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920631038594