Main Body

Introduction

What you Need to Know about this Book

Gina S. Matkin, Kris L. Baack, & Linda D. Moody

A note of gratitude:

This book was originally conceptualized as a textbook for a class at the University of Nebraska – Lincoln called “Interpersonal Skills for Leadership.” A book by the same name was originally written in 1996, with a second edition published in 2005 by Dr. Susan Fritz and colleagues (Fritz et al., 1996, 2005). Since the text was up for a new edition, we met with Dr. Fritz, who is a strong supporter of Online Educational Resources (as well as all free or low-cost texts for students). Dr. Fritz graciously offered to write a part of the Foreword for this text and offered great feedback and advice (aka, wisdom). Two of the three authors of this chapter have worked with Dr. Fritz for many years as graduate students, as staff, and, eventually, as faculty. We are grateful for her support and mentoring over the years, including with this current project.

INTRODUCTION

Opening Scenario

The room was filled with over 350 undergraduate students – mostly agricultural sciences and engineering majors who had enrolled in a required class called “Interpersonal Skills for Leadership.” The end-of-semester event brought all the sections of this class together for a final symposium. Our speaker, a Vice President from a prominent international company that often hired our students, held their attention much more closely than we had seen at any point during our semester of teaching!

During the Q&A at the end, one student asked the question many were thinking about. He asked, “What are you really looking for when you hire? What could I do that would set me apart from others who applied for the same position?” The Vice President’s answer seemed almost as if we had paid her to say it! She said, “Learn how to communicate well, work well on teams, resolve conflict, value diversity, serve your community, and work on your interpersonal skills.” The student seemed a bit surprised. He persisted, “But what about our technical or scientific skills? Don’t they count?” “Of course they do!” she responded. But if you graduate with a degree in your field from an institution such as this, we already expect you will be well-prepared for the technical aspects of your work. It is when you have the combination of good technical knowledge and skills, as well as well-developed interpersonal skills, that we will likely sit up and take a closer look. That is what often sets new graduates apart!”

This true scenario captures the essence of why we think this book and the class you are enrolled in are critical to you and your success. Taking the time to get to know yourself and what you bring to a team, workplace, classroom, or community will help you not only be successful but also build a happier life. This book is really all about you, so take advantage of it and learn more about who you are and what you want out of life. This, in combination with your field of study – whether it is agricultural sciences, natural resources, engineering, education, music, or any other – can be the thing that helps you stand apart, and it can help you craft the life that you want!

That’s a pretty big claim, so let’s dig into what this book and this class can do to help you accomplish these goals.

CHAPTER OBJECTIVES:

At the end of this Chapter, you will be able to…

- Explain the importance of interpersonal skills and the personal level of leadership as they apply to your personal and professional life.

- Describe the Social Change Model of Leadership and how it fits into the content of this text and class.

- Describe the value of Academically Based Service-Learning as a critical part of this class.

- Articulate the benefit of this class to you and how you will make the most out of it.

- Articulate a working knowledge of the class syllabus and how to use it to be successful in this class.

KEYWORDS: Academically-based Service Learning, Social Change Model of Leadership, Service-Learning,

Reflections

Take a few moments to consider and perhaps journal about these questions:

- Why did you take this class? If it is because it is required by your program, why do you think that is? Be honest and open about this.

- Consider some of the topics in this class: self-awareness, personal values, visioning, goal setting, etc. (see Table of Contents). How can you get the most out of learning about these topics and yourself? How does this help you be a better friend, team member, classmate, roommate, or leader?

- What is one expectation you have for yourself and for this class? Be sure and share this with your instructor and classmates.

About this Book

This book is based on two foundational models that help guide both the topics and the content within the book. These models are Academically Based Service Learning and the Social Change Model of Leadership (Higher Education Research Institute, 1996). These distinct but overlapping models are a perfect fit for this text and for you! We’ll describe each of them briefly below and then put them in the context of the book so you will know what to expect and how to get the most out of this text and the class!

Academically Based Service-Learning

Service-learning is a philosophy, a pedagogy, and a programming component under the umbrella of civic engagement. As a pedagogy, service-learning is a teaching tool instructors use to engage their students in serving underserved communities and/or marginalized populations. A unique underpinning of service-learning is the level at which communities participate to identify service experiences and to provide clarifying questions for community-based research. Higher education, at times, has not been a good partner with community agencies. In the past, faculty and students decided what was important and did not necessarily engage communities in dialogue leading to meaningful collaborations and partnerships. The tenants of academically based service-learning include aligning course learning objects to community-identified needs as determined by community leaders and members, thus creating a more productive and holistic experience for both the student and the agency.

Students and community members/leaders develop reciprocal relationships through the service-learning experience. Reciprocity can be best described as mutual respect between student and community, where power is equally shared. This differs from “volunteering” in that the student and community agency work together to identify and address issues that are mutually important to them. The student and community members are mutual teachers and learners. If service-learning is completed in this manner, both parties feel they received more than they gave. Because of this, service-learning is seen as building civic agency with students and communities.

Throughout the service experience, students are asked to journal their actions, insights, and course learning objectives through critical reflection. This is a crucial part of the process. Service learning, as well as journaling, are both considered High Impact Practices (HIP, see https://www.aacu.org/trending-topics/high-impact) in higher education. These practices have been identified based on evidence of significant educational benefits to students who participate in them. This book addresses many of the practices, thus creating a “high-impact” and high-quality experiential learning experience for you.

Consider the service component of this class as a sort of “laboratory” to practice and observe the topics you are studying and learning about. Engage in the service project as an integral part of the class and learning rather than seeing it as something separate. If you do this, we are confident that you will not only do well in the course, but you will achieve what our Vice President employer in the opening scenario defines as someone who goes beyond knowledge and content and deserves a second look!

Research Supports Service Learning

Participating in service-learning offers a multitude of benefits to students related to a broad range of social and cognitive outcomes (Eyler and Giles, 1999; Eyler, 2010). Research demonstrates that students who participate in service-learning “earned more credit hours, had a higher average GPA, and graduated at a significantly higher rate than did non SL students” (Lockeman & Pelco, 2013, p. 18). Additionally, students who participate in service-learning experiences have greater knowledge, awareness, understanding, and appreciation of societal issues (Astin et al., 2000) and report higher levels of academic and psychosocial well-being (Nicotera et al., 2015). Finally, service-learning has been shown to have a positive impact on student awareness of careers (Fisher, 2014) and to heighten career knowledge, skills, and team skills (Prentice & Robinson, 2010).

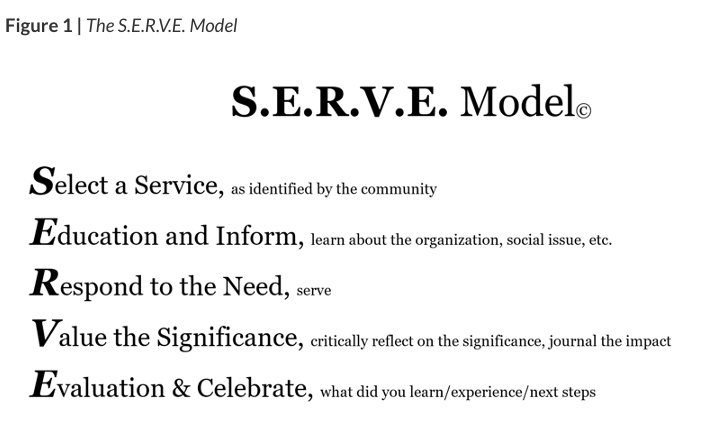

The S.E.R.V.E. Model for Service-Learning

The S.E.R.V.E Model was created by the University of Nebraska – Lincoln Volunteer Services Staff in 1996 as a way to frame service experiences for our students. It continues to be an important part of the process of service-learning and can help students better understand and navigate their service-learning experiences (see Figure 1).

The Social Change Model of Leadership

The Social Change Model (SCM) of leadership is a values-based approach to developing leadership for positive social change. It is based on the following premises:

- Leadership is socially responsible and affects change on behalf of others.

- Leadership is collaborative.

- Leadership is a process, not a position.

- Leadership is inclusive and accessible to all people.

- Leadership is value-based.

- Community involvement and service is a powerful vehicle for leadership.

Source: Komives & Wagner, 2017, p. 10

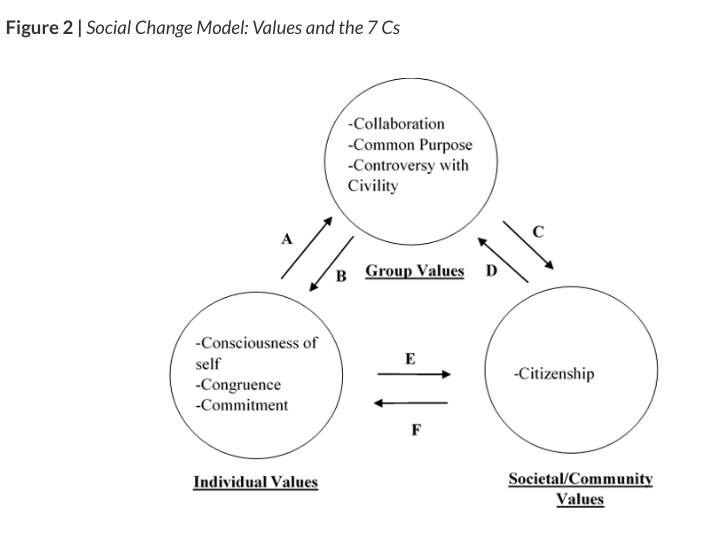

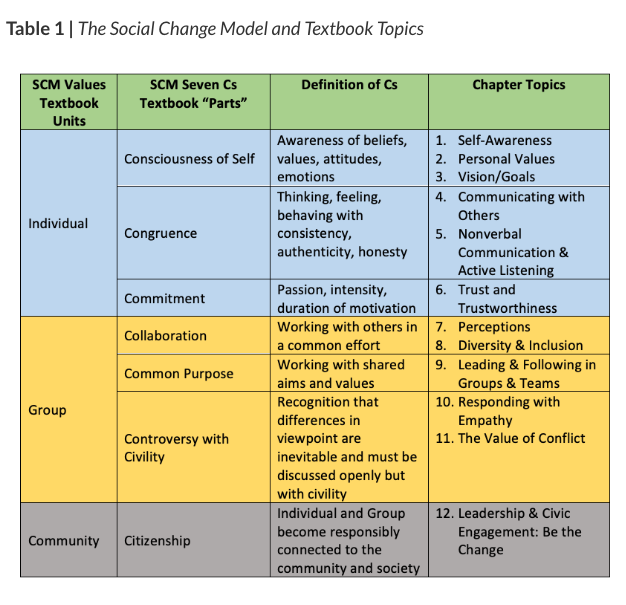

Values of the model include Individual, Group, and Community. Nested under these values are the “7 Cs” that correspond to each of these values (see Figure 2). Learning about and working through Individual and Group values prepares students for Citizenship. Created by the Higher Education Research Institute (HERI; 1996) of UCLA, the model promotes the relationship between leadership and citizenship.

For most of us, growing up, we thought of “being civically responsible” as being educated on current issues and, according to our values, voting in local and federal elections. Today we know voting is important, and it is one way we may exhibit being a civically engaged citizen of our community. But on a day-to-day basis, what does “making a difference” look like? You may make a difference by taking care of your sick roommate or sharing your class notes with a classmate. Are these actions making your community a better place?

This text is structured around the Social Change Model of Leadership. Each Unit explores a different level of Values (Individual, Group, Societal/Community). Each Unit is then divided into Parts that correspond to the Seven Cs that fit within. You will learn and practice (through your service project) the skills related to each of these. Table 1 illustrates this structure and how the specific topics of this text fit within this structure.

Putting it All Together – Let’s Get Started

Now you have a good sense of how this text is structured, the models which frame it, and the importance of the content in this class. This is a great time to review your class syllabus and the topics we will cover to do a bit of preparation and set yourself up for success.

The following activities offer some ways for you and/or the class to begin this journey. Your instructor may use some of these to get the class started, but some are more about you and doing some personal reflections. We encourage you to take advantage of these and, as we hope you will do with this class overall, dive deeply into learning and growing.

At the end of the semester, we often have our students offer a bit of advice to new students who will be in the class the next year. These are shared on small slips of paper and stowed away until the first day of the new class. There are always a few that are repeated, such as: “READ the text” (we like that one!), “start your service project as early as possible,” and “get to know your classmates.” What I would like to leave you with, however, is one that always catches students’ attention. Although it is often written in different ways, the gist of it is: “Remember that you will get out of this class what you put into it! Invest wisely!” We hope you will “invest wisely in this class.” After all, it is you who is doing the investing, and you who will be invested in. This is definitely a win-win for you and for your future!

A FINAL NOTE ABOUT THE AUTHORS

The chapters of this text are authored by a variety of scholars and practitioners who are valued experts in leadership and, more specifically, in the areas they are writing about (see editor and contributor bios). Because they come from different backgrounds and experiences, you might notice some different “voices” in their writing. This is an intentional aspect of this book to expose you to different perspectives, styles, and ways of thinking! We encourage you to embrace these differences (see Chapter 8 for more on embracing differences) and enjoy the journey. The authors and editors of this text are all dedicated to your development and success. We all wish you a fruitful and enjoyable journey this semester!

ACTIVITIES

The Name Game

Purpose: to begin to learn the names of others in the class and remember as many as possible

Sit in a circle, if possible, but even if you cannot, start in a logical place and go around the room. Each student introduces themselves and then shares one way we can remember their name. For example: “My name is Courtney. You can remember my name because I am on the tennis team and, of course, play on a court.” Or “I am Zane. You will definitely remember it because I am kind of a zany person, and I love to make others laugh!”

Depending on the size of the class, you might have each person repeat the ones before them and how to remember their name before doing their own introduction.

EXTENSION: This activity can lead to a fun way to begin the second day of the class by seeing who remembers the other students’ names. It has been our experience that often students first recall the way to remember the name, and that leads them (or someone else in the class) to shout out the name.

Syllabus Expert Activity

PURPOSE: To help students become familiar with the syllabus. To reinforce the most important parts of the syllabus. To help students engage with each other and reinforce names.

After reviewing the class syllabus, your instructor will assign sections of the syllabus to each student by providing slips of paper with their assigned section on it. These may be instructor and/or class information, specific assignments, due dates, topics, specific class policies, etc. The paper will indicate the page number so you find the correct information.

You will then take some time to read and review your assigned section and become the “class expert” on the section your instructor has assigned.

Students will then mill about the room and introduce themselves to other students (remember to use your name and the way to remember it from the Name Game). You will then explain the part of the syllabus you are assigned to the other student. Your instructor will call “time” every 2 minutes, and students move on to meet with someone else. This will continue until there has been time for students to engage with several students in the class.

After the engagement part of the activity, you will return to your seat and your instructor will ask what you learned. They may also choose to ask the class questions about the most important parts of the syllabus and make sure those were communicated clearly during the activity.

Personal Reflections Activity

PURPOSE: To help you consider how you can get and give the most in this class.

This activity may be done during class or may be assigned for you to do on your own.

Using the text and/or the syllabus, review what this class is about, the broad topics we will cover, and how it can help support you and your academic, personal, and professional goals.

- Write down the class topics that you believe you are good at. Ask yourself and journal about how you can be open and continue to learn more about these topics, as well as how you might role model these to help the rest of the class learn.

- Now write down topics that you think you most need to learn about or practice. Ask yourself and journal about what you can do to be open to growing and practicing these, as well as how you might be open to learning from others in the class.

- Journal about what you will do to get the most out of this class (remember, you get out what you put in) through engaging in the class and your service project.

REFERENCES

Astin A. W., Vogelgesang L. J., Ikeda E. K., Yee J. A. (2000). How service learning affects students. Higher Education Research Institute, UCLA.

Eyler J. 2010. What international service learning research can learn from research on service learning. In Bringle R. G., Hatcher J. A., Jones S. G. (Eds.), International service learning: Conceptual frameworks and research (Vol. 2, IUPUI Series on Service Learning Research, pp. 225-242). Stylus.

Eyler J., Giles D. 1999. Where’s the Learning in Service-Learning? Jossey-Bass/Wiley.

Fisher, W. L. (2014). The impact of service-learning on personal bias, cultural receptiveness and civic dispositions among college students (Doctoral dissertation). SUNY Buffalo

Fritz, S., Brown F. W., Povlacs Lunde, J., & Banset, E. A. (1999). Interpersonal Skills for Leadership (1st ed.). Prentice Hall.

Fritz, S., Brown F. W., Povlacs Lunde, J., & Banset, E. A. (2005). Interpersonal Skills for Leadership (2nd ed.). Pearson.

Higher Education Research Institute. (1996). A social change model of leadership development (Version III). UCLA. https://www.heri.ucla.edu/PDFs/pubs/ASocialChangeModelofLeadershipDevelopment.pdf

Komives, S., & Wagner, W. (2017). Leadership for a better world: Understanding the Social Change Model of leadership development (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Lockeman, S. L. & Pelco, L. E. (2013). The relationship between service-learning and degree completion. Michigan journal of community service learning, 20(1), 18-30. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.3239521.0020.102

Nicotera, N., Brewer, S., & Veeh, C. (2015). Civic activity and well-being among first-year college students. International journal of research on service-learning and civic engagement, 3(1). https://doi.org/10.37333/001c.21589

Prentice M, Robinson G (2010) Improving student learning outcomes with service learning. Report, American Association of Community Colleges. Washington, DC.