Main Body

12 Leadership & Civic Engagement: Becoming the Change Maker

Jason Headrick

“You will not always be able to solve all of the world’s problems at once, but don’t ever underestimate the importance you can have because history has shown us that courage can be contagious and hope can take on a life of its own.” – Michelle Obama

Congratulations! You have reached the final chapter in this text. This means you have had a chance to study, reflect on, observe, and practice your interpersonal skills. For many of you, it also means you have completed a community-based service-learning project where you have not only made a contribution to your community (which served as a laboratory for the concepts in this class) but that you also benefited from that agency by having an opportunity to practice and observe all that you are learning.

Perhaps you have become more self-aware (Chapter 1), considered and proactively practiced your values (Chapter 2), created a vision and learned how to set goals (Chapter 3), improved upon your ability to communicate effectively and use good nonverbal/active listening skills (Chapters 4 & 5). Maybe you have learned about the importance of trust in relationships, leadership, and life (Chapter 6), been challenged to consider your perceptions of the world around you (Chapter 7), reflected on your own identity and how knowing yourself well can help you be a more inclusive leader (Chapter 8), or learned about the importance of working effectively in groups and teams (Chapter 9). You may have learned to consider and practice empathy (Chapter 10) and practiced this as well as other positive approaches to managing conflict (Chapter 11).

In this final chapter, you will bring all of this together to develop a final Personal Civic Leadership Philosophy. Consider this an extension of the Personal Leadership Philosophy you created in Chapter 3: Defining my Vision and Setting Personal Goals. This chapter will help you make some of the larger connections between yourself, the way you view interpersonal skills, and the type of leader you want to be and will build on these concepts by helping you examine your own level of citizenship. It will further provide resources for you to see citizenship from a variety of perspectives, including videos and activities on how to strengthen your civic agency, align your social justice interests with community needs, and enhance your civic-minded leadership. So, let’s get started!

CHAPTER OBJECTIVES

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to…

- identify key concepts of civic agency, civic engagement, civic leadership, and social capital.

- explain civic agency and citizenship as it relates to you, your friends, and your community.

- evaluate and integrate the concepts of interpersonal skills and social capital as they relate to community engagement in your leadership philosophy.

- connect your personal leadership philosophy to your future goals of civic engagement and community development.

KEYWORDS: Citizen, civic agency, civic engagement

Here are some important words for you to know for this chapter, but also to help you move forward as a leader within your community.

- Citizen: individuals who focus on taking care of themselves by doing things like obeying the law, paying their taxes, contributing resources, supporting community efforts, and donating. They are honest, fair, respectful, and self-reliant. They try not to be a burden on the community.

- Civic Agency: the capacity of individuals and/or groups to enact positive change.

- Civic Engagement: contributing and working to make a difference in the public (or civic) life of our communities and developing the combination of knowledge, skills, values, and commitment to make that difference.

Case Study: Making Program Decisions

Raji and Becky met during their service-learning experiences at an area non-profit in a leadership program. Encouraged by their course instructor to serve in areas they were unfamiliar with or had no experience, they did not know where to start. They used the service-learning project summary sheet to rank programs that met the course instructor’s expectations. Although it was difficult at the beginning to adjust their schedules, find transportation, and complete their service-learning agreement, Raji and Becky jumped in.

During an orientation with the non-profit, they learned they both selected the same program. While serving, they learned they both were the first to attend college in their families, both had volunteered with high school organizations, and both were anxious about completing the service-learning experience. They both were uncomfortable at the beginning wondering if they had made the right choice.

Raji, an English Language Learner, did not understand why the middle school children he was serving were not motivated to learn and did not finish their activities during homework club. He was an excellent student, and English had come quite easy to him. Becky studied a second language during high school and attended a two-week study tour to Costa Rica. The middle school students enjoyed Becky as they could relate as she struggled to use her second language to teach the activities. They completed their activities on time for Becky. Raji and Becky were concerned about the discrepancies in how the students responded to them and discussed this with their site supervisor. Then, they shared their concerns and conversation during class with their students.

Over time, Raji and Becky began to trust each other and ask clarifying questions to themselves, their peers in class, and their course instructor and site supervisor. Their site supervisor was helpful in providing guidance and suggested several methods to use. Throughout the semester, the middle school students responded to Raji and Becky’s encouragement and teaching styles. Homework was being completed in a timely manner and was more accurate. Toward the end of the semester, Raji and Becky wondered how they might continue with the leadership program, in addition to identifying and removing barriers faced by English as a second language students and their families.

Case Study Questions

1. What societal issues do Raji and Becky want to be part of solving in their service project?

2. What values and leadership characteristics are Raji and Becky demonstrating in working to solve the issues and discrepancies with students not completing assignments?

3. What recommendations would you give Raji and Becky to help them move forward?

Become a Community Focused Citizen

How will you be a positive change in your community? Will your actions contribute to the common good? These are questions civic leaders ask themselves. All positive actions, whether small or big, can lead to strengthening our communities. Westheimer and Kahne (2004) provide a lens into how to become engaged in one’s community. ‘Citizen,’ for the purpose of this chapter, refers to being a member of a community, whether local or global.

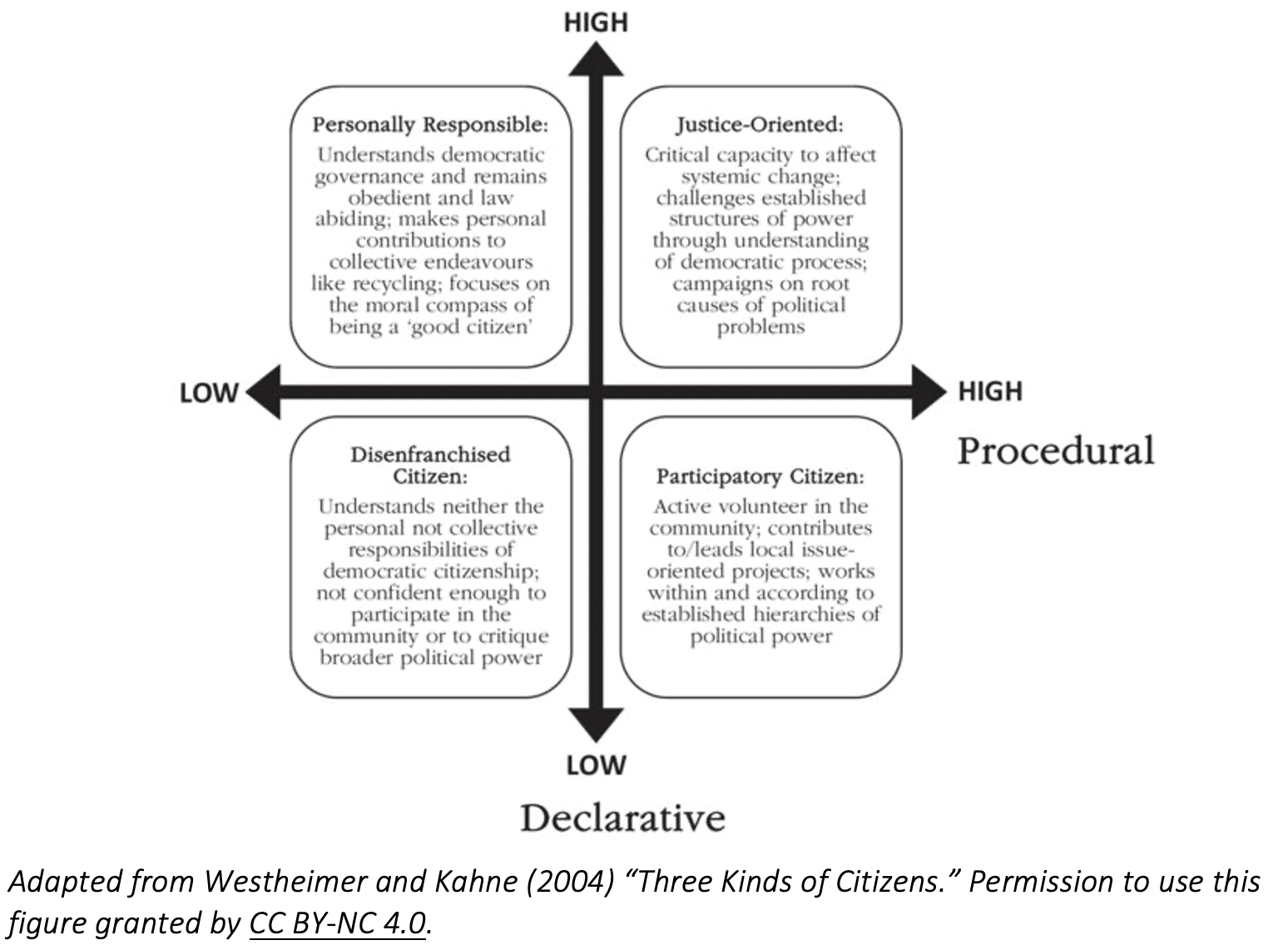

Westheimer and Kahne (2004) describe four kinds of citizens: (1) the personally responsible citizen; (2) the participatory citizen; (3) the justice-oriented citizen; and (4) the disenfranchised citizen. To better understand these concepts of citizenship, let’s look at voting rights in the United States. For example, as a personally responsible citizen, people vote in primary and general elections. As a participatory citizen, some serve as a voter registrar and assist a local non-profit in educating community members about the issues on the ballot, as well as to assist individuals in how to become registered to vote. A justice-oriented citizen, may be further interested in systemic positive changes to voter registration laws and will call, write, and visit with elected officials to ensure all voters have access; however, a disenfranchised citizen may not vote or participate in the process at all because they feel they do not have the necessary information or feel that the current process is not inclusive for them. These types of citizens are described in Figure 1.

Figure 1 | The Declarative-Procedural Paradigm

Becoming a Community-Focused Leader

What does it mean to be a civically minded leader? How do you see others making a difference in the community? Is it through their service to one or many causes, organizing a food drive, voting rights, or being a good steward through philanthropy? Practicing the ideas behind civic engagement and being a leader who seeks to bring out the best in self, in others, and in their community is difficult work. A focus on respecting your values and the values of others allows leaders to be confident in their leadership roles and engagement.

Defining Community

You may have heard the term community throughout your life. We often think of a community as a place-based area where we live, but a community can also be a group of people you feel comfortable with or who share like-minded ideas. A community can be both a place and a space. Examples of community may include your neighborhood, a faith-based place like a church or synagogue, an organization rooted in commonalities like a PTA or an LGBTQ+ rights group, or it might include places like a college campus or work environment. Some of you may be wearing a t-shirt that represents your hometown or your college name and mascot. These are examples of communities and are prime places that require leadership to advance and continue. As a member of a community, we can represent our values, and they can simultaneously be a space where we are able to be our authentic selves. Typically, communities are places of trust, communication, and a range of other representations of the context we have discussed throughout the book. You can make an impact on a community through membership, service, dwelling, advocacy, and a range of other ways. This chapter will help you frame the importance of being engaged in your communities and demonstrate how to make some of the larger connections.

Civic Agency

Civic agency involves the ability of members of a community to work together across differences, such as political ideology, traditions of faith, income level, geography, and race and ethnicity (American Democracy Project, 2022; Fowler & Beikart, 2020). Other researchers define agency as having the ability to identify issues of power and inequity to act in a way that promotes individuals and communities (Campano et al., 2020).

When individuals team up with other individuals, they can address challenges across a community, help to solve problems, and create common ground. When you decide to become involved in the process, you are acting on your own degree of civic agency. At this point, you have identified a challenge in your own community and you decide to act toward a solution or a compromise, to speak up on behalf of others, or to develop a plan to address the work that you have identified that needs to be done.

Civic Engagement and Leadership

Challenges across our communities typically require the work of many instead of a select few. The idea of being a civic leader allows us to ask how we can create change and progress in our communities, but there is much discussion focused on what civic leadership looks like in the 21st century.

Many traditionally college-aged students may not have prior exposure to civic duty beyond experiences with mandatory volunteer work through a school or church setting, which is a direct marker for Generation Z (Seemiller & Grace, 2017). While Perrin and Gillis (2019) did find that college graduates are more likely to volunteer and vote in presidential elections, only 15.9 million Americans were enrolled in colleges and universities in 2020 (National Center for Educational Statistics, 2022). Many students do not have direct shared life experiences that have shaped their interest or knowledge in sustaining and building social capital and community development. Without this catalyst, there may be decreased interest or understanding of how individuals can truly create an impact across our communities through engagement and service. Thus, it becomes imperative for those who have access to higher education to represent their communities.

A term used to bring community-based engagement under one umbrella is civic engagement. Students contribute and work to make a difference in the public (or civic) life of communities, and they must develop the combination of knowledge, skills, values, and commitment to make that difference. It means promoting the quality of life in a community and solving public problems through both political and non-political processes. Civic engagement is undergirded by constructs of collective action and social responsibility (Ehrlich, 2000).

Modern representation of civic engagement can take many forms. It can take traditional forms, such as helping to organize a clothing drive, working as a volunteer at your county fair, or signing up to help a political candidate get elected through a door-knocking or text campaign. But it can also take a more technological form. Cho and colleagues (2020) found that digital civic engagement allowed citizens the opportunity to highlight challenges in fairness and access and to point out larger societal problems through social media and other online options. If you are activating your ability to aid or act on behalf of your own values and for the benefit of others, you can be engaged in civic engagement and, through your service, provide civic leadership.

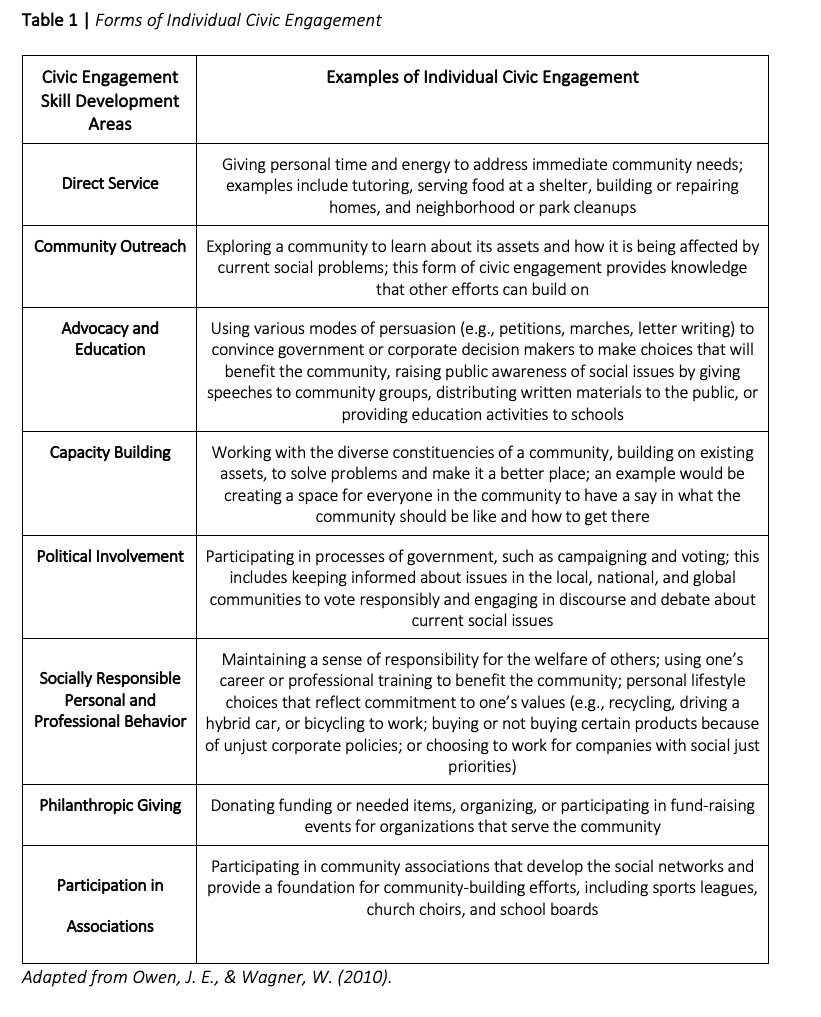

We can also examine civic engagement and leadership from the perspective of the Social Change Model (Komives & Wagner, 2017). Let’s talk through some examples. These forms of engagement can range from a residence hall food drive for Thanksgiving to a bike-a-thon raising money to support an earthquake in Haiti. Socially responsible personal and professional behavior involves looking at how you take care of others and live according to your values. This can be a great example of commitment when you know yourself and your values (Consciousness of Self), and you live your beliefs/values (Congruence). Political involvement includes campus, city, state, and national communities. For most of us, the first step is registering to vote and researching candidates and issues. Our values (Consciousness of Self) determine the individuals and/or causes we choose to support (Congruence). On today’s campuses, the emphasis on diversity, equity, inclusion, and access provides an example of building capacity. Actions and events that celebrate individual differences and the richness of inclusion provide the ideal environment for growth and resolving challenges. Table 1 presents various forms of individual civic engagement.

Many service-learning classes begin with community research, as the needs of the community must direct the service to be provided. Individually, prior to serving, it is essential to ascertain the need of the service group or agency. Direct service is sharing your gifts in serving others. Most communities have numerous and various non-profits for one to select from. Engaging in citizenship usually implies working with others within a shared community. Komives & Wagner (2017) state that anyone can be involved in their community for the common good, yet there are skills and knowledge that can make that involvement more effective. Key factors include “understanding social capital, awareness of the issues and community’s history, empowerment and privilege, social perspective taking and coalition building” (Komives & Wagner, 2017, p. 181).

Putnam (2000a) defines social capital as a type of civic engagement where a community benefits from citizens who are actively engaged with each other and their community. In addition, there are two components of social capital: bonding and bridging (Putnam, 2000b); Putman & Goss, 2002). Social interactions limited to individuals who are like each other (e.g., student organizations for science majors, etc.) are referred to as bonding. Bridging refers to social interactions among diverse groups of people (e.g., student government bringing students of all majors together to address common campus concerns, etc.). College campuses have a plethora of social capital examples. Individuals who regularly interact with each other are more likely to trust one another, help each other, and more easily resolve common challenges.

The Leadership Connection

Learning about the foundations of leadership and interpersonal skills are vital to our understanding of ourselves as a leader and our capacity to be a leader in our organizations, in classrooms, in the workplace, across industries, and in our communities. The goal of this book has been to provide foundations that demonstrate the use of these skills across all of these contexts, while the goal of this chapter has been to provide you with a lens to understand civic leadership and engagement. This last section taps into the lessons learned throughout the preceding chapters to help you better understand your place as a leader and to understand the challenge to you to become an engaged civic leader in your current or future communities.

Being aware of who we are and how we represent our authentic selves to others is of foremost importance in building on our abilities to be a leader. The self-concept and self-esteem we have for ourselves are, in fact, our own foundation and are imperative to opening ourselves up for the lessons of this text. As we dig deeper into our values, we find out what is important to us and how to drive our passion to serve others and our communities. You have also been challenged to define your own understanding of leadership and set up your own vision and your personal goals. Goal setting is a skill that will serve you throughout your entire life as you prepare to be a leader in your chosen profession and across various systems. Goal setting allows you to create a path for yourself and put some accountability into your desired actions and has been shown to positively affect your self-efficacy and motivation (Schunk, 2003).

Communication seems like a simple act, but you have read, and no doubt discussed with others, how the act itself is complex and requires us to tap into our other skills and consider the ways we work with people. Being an effective communicator calls on us to use active listening and to process the message we are trying to relay to others. We must consider the contexts of the situation and tap into our understanding of nonverbal communication as well. When we know how others prefer to communicate and how we can better communicate with others, we become a more impactful leader and member of a team or community.

Trust is one of the foundations of any relationship. Building trust can take time to develop with others and requires us to become vulnerable with others. This can mean we have to open ourselves to others and tap back into our active listening skills so they feel comfortable being vulnerable with us. You will experience trust in various forms throughout your entire life. It’s a fundamental – and often unspoken – part of being an impactful leader and will determine how you live to be your authentic self with others, at work, and in your future community. Trust also plays into how we perceive others and explore our own perceptions throughout life.

Working with others requires us to understand their individual stories and the parts of their culture that we see, but also those parts of someone’s diversity that we cannot always visibly see. The idea of surrounding yourself with diverse individuals and making sure, as a leader, you work to include others by creating spaces where individuality is celebrated, and people are allowed to be versions of their best selves will truly impact the way you navigate as a leader. Tapping into your understanding of others and using your own emotional intelligence shows others that you are genuine and value people. Half of the battle of working in a group or team is showing your trust in those you surround yourselves with, and this asks you to be a leader who values communication and ensures equity exists for everyone to be involved in the work to be done.

Leadership is not always easy. Sometimes it requires us to tap into empathy so we can understand the experiences of others to make the best decisions in the moment and to help edit our response and behavior when we work with individuals. Because we are all complex individuals, conflict is inevitable in some form, and that is not a bad thing. Conflict can make us find innovative ways of doing our work and bring about creativity and improved task response. Through understanding our own personal leadership components discussed in this book, we become more informed about how to take the best parts of ourselves and apply it in a bigger application of leadership. Leaders who understand themselves and have a good appreciation of their talents and abilities make the best leaders and increase their capacity to lead others around them.

Summary

The idea of civic engagement combines many components of leadership into a form of action. This text is intended to help you consider and practice those leadership components, not only so you can be at your best personally but so you can also consider how, as a leader, you can serve and impact your community and the world.

As leaders, we have the capacity to impact change in our immediate environments (work, campus, student organizations), but also can create action in our broader communities. Being civically engaged means you are an active member in your community. This doesn’t mean that you must be involved in three organizations, have a job, and balance professional and personal responsibilities. This means you are taking the time to consider the impact you can have on your community and using your leadership talents and skills to find the best path forward to create change and spark new ideas.

Being someone who is focused on civic leadership and engagement means that you want to see your community improve and develop in new and exciting ways. We often think about ways we wish our communities can improve, and we may ponder on who would be best to create that change. If you have found yourself thinking these things, the answer could very well be you. You have a vision for how things could improve and using your abilities and resources can help you set a path forward to be a catalyst for idea development or assisting others. Civic engagement does not always mean you have to create a nonprofit or raise money for a new community center.

Being someone who is civically engaged means you want to see the places and spaces you enjoy improve, and you are willing to contribute to that improvement in one way or another. This has the added benefit of helping you become more successful in your personal life and your work as well. Recall from the first chapter of this text when our vice president told the students she wanted more than just technical skills in those she hires. She wanted people who had good interpersonal skills and were involved in their communities and felt that these gave them a professional advantage. When you combine your vision for your community, your workplace, or toward the work of an organization, you are combining your leadership fundamentals for the greater good. This is how you become the most impactful version of yourself in your community, your work, and in your personal life. We believe in the good you will do.

The Final ACTIVITY

Personal Civic Leadership Philosophy, Part 2

To begin this exercise and craft an extension of your Personal Leadership Philosophy (called your Personal Civic Leadership Philosophy), reflect on your reflections, statements, and philosophy created in Chapter 3, and how you came up with those statements. How do they represent who you want to be as a leader? Keep those statements handy as we begin this next exercise. This will help provide insights and linkage for you into how you can develop agency and consider how you can become a civic leader in your own communities.

Consider the following questions before we move on to Part 2 of this process:

- Do these statements still represent who you want to be as a leader, or have they changed since your participation in this course?

- How do your values reflect these statements?

For the next phase of this exercise, think about the town you grew up in. This may be your hometown or another city or town that you consider to be the town you grew up in. After you have identified your answer, please work through the questions below.

Name of town: _______________________________

What are the best things about the town you selected? What makes it better than other towns? Let’s call these the town’s strengths.

1.

2.

3.

What are the things your town needs to improve on? What, if anything, hinders the town when you compare it to other places? We will call these the town’s weaknesses.

1.

2.

3.

For the next two questions, think about how others see your town or what parts of your town are not living up to their fullest potential. Are there hidden gems that make it a great place to live compared to other places? Think about how different generations of citizens view the town.

What are the good things that your town could capitalize on that it does not currently have or do? Is there something that you think could help the town be a better version of itself? What are things in place that could benefit the town in long-term planning? Let’s call these opportunities for the town.

1.

2.

3.

Now consider the things that could make a negative impact on your community. Are there things that could harm it or things that pose a threat to the existence or future economic stability of the town?

1.

2.

3.

You have just conducted a SWOT analysis. You were asked to choose a town that was either your hometown or a town that has sentimental value to you. Through the questions, you took a close look at the town using a SWOT process. You identified the Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats (SWOT) in place for the town you identified earlier. A SWOT analysis allows us to examine an organization, idea, or, in the case of our exercise, a place like a town.

A personal SWOT analysis allows you to examine the internal and external influences that impact your personal and professional life. This allows you to understand how to set yourself apart from others and strive to achieve your personal best. It also allows us to take a close look at ourselves, which is great when processing our own leadership capabilities and skills.

Using the SWOT grid below as a guide, now conduct a SWOT on yourself. You can usually easily identify your shortcomings but focus on the things you are good at. You are your own biggest supporter, and focusing on your Strengths allows you to build your self-confidence. The Opportunities and Threats sections can be the most difficult for individuals because they ask us to reflect critically on ourselves and do a bit of future forecasting on the things that might impact our own futures. It can be helpful to consider the opportunities you have that are forthcoming to meet your goals or to help you advance in other areas of life. In a similar thought process, identifying the Threats that exist in your life (relationships, health, finances, etc.), your daily routine, and other things that might be beyond your control are great to put here. When you are ready, focus on yourself and conduct a personal SWOT analysis.

SWOT Analysis Grid

After you have conducted your personal SWOT, take some time to answer the questions below. These questions will help you develop some larger leadership development goals and help you position yourself as a civic leader in your own community.

Questions to Consider for Reflection

(Note: It might be helpful to review your activities and your Values Assessment from Chapter 2 for these questions.)

What are my top 5 values?

- How do my values impact the way I work with others and with the community?

- How do my values shape me as a leader?

- What would people say are my strengths and values as a leader when I am not in their presence?

- How can I implement the larger lessons of this class into my own leadership style? What are the concepts from this class I want to build into my life?

- How do I personally contribute to the community?

- How can I be more intentional with my own community engagement/ service to the community?

- What actions and goals can I set to make this happen?

I can take the following steps to make an impact on my community:

1.

2.

3.

Using the reflective activities above, you have been able to identify your leadership assumptions, beliefs, and values as they relate to your community and the broader world in which you live. The next step is to put all of this together to create a Personal Civic Leadership Philosophy (PCLP), which is an extension of the PLP you created in Chapter 3 and broadens your leadership reach to include the ways in which you hope to contribute and affect change in your community, organization, country, or beyond.

We encourage you to take a few minutes to review your responses above and your PLP and reflections from Chapter 3. Then, take 15-30 minutes to write out a draft of your PCLP with a focus on how you would use your values, beliefs, and leadership skills to impact your community and beyond. Just as in Chapter 3, it may be very helpful to just give yourself time to write without any editing. Instead of deleting or editing what you have written, simply write the statement again in another way. Setting a time goal (for example, I will write for 30 minutes without stopping or editing) can be helpful as you try to get ideas out of your head and onto paper or a computer screen. After writing, take some time to edit and refine what you have written. Not everything you write needs to be in your final PCLP, and you may also realize important ideas need to be added. Separating writing from editing allows you to make progress without getting stuck writing and re-writing the same sentence.

When you are ready…go!

Now What?

For the last section, consider your responses to the SWOT, the questions above, and the statements you created under your Personal Leadership Philosophy, Part I. How can you shape these responses to be larger goals and takeaways from this class? How will they guide you through college and into your young professional life? Reflect on the Personal Leadership Philosophy that you developed in Chapter 2. How can you use your philosophy and expand on it with the other chapters and content from this book? In this section, you will develop statements.

Now, consider all that you have done; your responses to the SWOT analysis, the questions, and reflections, your original Personal Leadership Philosophy PLP – Part I), as well as your free write and edits of your Personal Civic Leadership Philosophy (PCLP – Part 2). How can you shape these responses to be larger goals and takeaways from this class? How will they guide you through college and into your young professional life? How can you use your philosophy and expand on it with the other chapters and content from this book? In this section, you will develop statements that show your insights and experiences and how you can contribute to the community in ways that are consistent with your unique skills, abilities, strengths, and aspirations.

For the last section of your PCLP, you will develop 3-5 statements that showcase your personal and professional goals and how they extend into your current (or future) community. These can expand on how you will engage as a civic leader, become involved in community development, or make an impact on others. These statements constitute your Goals for your Personal Civic Leadership Philosophy and will guide you toward making decisions on how and what to be involved in. It might be helpful to review the Goal Setting section of Chapter 3 to help with this. Example statements are listed below for your consideration.

Example Civic Leadership Statements:

- I commit to serving a non-profit in my community once per month because….

- I plan to run for political office before the age of 30 because….

- I will represent my community by doing….

- I will choose opportunities to serve others through these criteria….

My Civic Leadership Goal Statements:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

REFERENCES

American Democracy Project. (2022, October). American Association of State Colleges and Universities. Retrieved October 3, 2022, from https://www.aascu.org/programs/ADP/

Campano, G., Ghiso, M. P., Badaki, O., & Kannan, C. (2020). Agency as collectivity: Community-based research for educational equity. Theory Into Practice, 59(2), 223–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2019.1705107

Chambliss, J. J. (2004). John Dewey’s 1937 lectures in philosophy and education. Education and Culture, 20(1), 1–13. https://docs.lib.purdue.edu/eandc/vol20/iss1/art2

Cho, A., Byrne, J., & Pelter, Z. (2020). Digital civic engagement by young people. UNICEF Office of Global Insight and Policy. https://www.unicef.org/globalinsight/reports/digital-civic-engagement-young-people

Ehrlich, T. (Ed.). (2000). Civic responsibility and higher education. Oryx Press.

Fowler, A., & Biekart, K. (2020). Civic Agency. In R. A. List, H. K. Anheier, & S. Toepler (Eds.), International encyclopedia of civil society (pp. 1–6). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-99675-2_69-1

Komives, S. R., & Wagner, W. (Eds.). (2017). Leadership for a better world: Understanding the Social Change Model of Leadership Development (2nd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

National Center for Educational Statistics (NCES). (2022). Fast facts: Enrollment. https://nces.ed.gov/fastfacts/display.asp?id=98

Owen, J. E., & Wagner, W. (2010). Situating service-learning in the context of civic engagement and the engaged campus. In B. Jacoby (Ed.), Establishing and sustaining the community service-learning professional: A guide for self-directed learning. Campus Compact.

Perrin, A. J., & Gillis, A. (2019). How college makes citizens: Higher education experiences and political engagement. Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World, 5. https://doi.org/10.1177/2378023119859708

Putnam, R. D. (2000a). Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. Proceedings of the 2000 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work – CSCW ’00, 357. https://doi.org/10.1145/358916.361990

Putnam, R. D. (2000b). Bowling alone: America’s declining social capital. In L. Crothers & C. Lockhart (Eds.). Culture and politics. Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi-org.libproxy.unl.edu/10.1007/978-1-349-62397-6_12

Putnam, R. D., & Goss, K. (2002). Introduction. In Robert D. Putnam (Ed.), Democracies in flux: The evolution of social capital in contemporary society. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/0195150899.003.0001

Schunk, D. H. (2003). Self-efficacy for reading and writing: Influence of modeling, goal setting, and self-evaluation. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 19(2), 159–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/10573560308219

Seemiller, C., & Grace, M. (2017). Generation Z: Educating and engaging the next generation of students. About Campus, 22(3), 21–26.https://doi.org/10.1002/abc.21293

Westheimer, J., & Kahne, J. (2004). What kind of citizen? The politics of educating for democracy. American Educational Research Journal, 41(2), 237–269. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312041002237