Main Body

7 Perceptions are Only From My Point of View

Heath E. Harding

“We are in this together, by ourselves.” – Lily Tomlin, comedian and actress

INTRODUCTION

An adage about leadership and change says, “If you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go far, go together.” You can accomplish many things individually, but you can achieve even more when working with others. Social change requires a tremendous amount of work. It will be essential to learn how to work with others to accomplish your goals.

This chapter will discuss how our perceptions influence our thinking and our relationships with others when creating social change. As humans, we live in social systems. We have many social systems in which we interact: our families, our workplaces, our friends, etc. Our individual experiences and our perceptions of those experiences impact how we engage in these different social systems. In other words, our perceptions lead to judgments about people. We likely cannot stop making judgments about people and events in our lives; however, we can consciously influence the process and make intentional judgments about ourselves, others, and the world around us. So let us get started increasing your understanding of how this works.

CHAPTER OBJECTIVES:

By the end of this chapter, you will be able to…

- understand why perceptions are essential to successful social change.

- understand how we create perceptions.

- examine how your perceptions impact your leadership.

- apply tools to identify and cultivate awareness of your perceptions.

KEYWORDS: Perception, meaning, viewpoint, stories, understanding experiences

Perception is defined as our experience of an event or person. We collect, organize, and interpret data on events throughout our day. We never collect all the data. Our brains often reject some data because it does not fit prior patterns already in our minds. We then organize the data we have selected out of the pool of data and assign plausible meaning to the limited information we have collected and organized. These brain processes happen at blazingly fast speeds in our minds, and we often are not consciously aware of the process. Usually, we are only mindful of the end product: our judgments of events and, more importantly, people.

In the Social Change Model (Higher Education Research Institute, 1996; Komives et al., 2005, 2006), interpersonal relationships form the model’s core, making it critical to know how and when you are creating perceptions about your experiences and the people you encounter. Your perceptions and, ultimately, your judgments directly impact your interpersonal relationships. In the Social Change Model, leadership is inclusive, collaborative, and value-based. Our perceptions influence our actions to be inclusive of ideas and people, impacting our success in leading collaborations. Our perceptions over time create and reinforce our values.

Humans are meaning-making machines. We take sensory data, look for patterns, and then organize it into a story that makes sense. We organize all the data into patterns that we can understand. The meanings and understandings we create are called our perceptions: “Perception (from the Latin perceptio, meaning gathering or receiving) is the organization, identification, and interpretation of sensory information in order to represent and understand the presented information or environment” (Schacter et al., 2011).

Perceptions are Mini-Stories

“We are, as a species, addicted to story. Even when the body goes to sleep, the mind stays up all night, telling itself stories.” — Jonathan Gottschall, The Storytelling Animal: How Stories Make Us Human

It is helpful to think of our perceptions as mini-stories we create throughout the day. We take information about our experiences and people and use them to develop a story that will help us make sense of all the data. This meaning-making process happens all day long, often subconsciously. One of the best ways to see this in action is to go to a public place where you can observe strangers: a large class, a public spot on campus, a street corner, public transportation, a shopping center, etc. Pick a stranger to observe for five minutes. Make some mental notes about what you think about this person. Is this person friendly? Is this person someone you would like to get to know? Is this person wealthy?

Your answers to these questions above and others we could pose are your perceptions about the stranger. The accurate answer to the questions above is “I don’t know.” The person is a stranger, and you do not have data to determine if they are friendly, wealthy, or someone you would like to get to know. Without more data, you do not know how warm or rich the stranger is, yet our brains cannot help but form assumptions. Our brains organize the data that we notice into perceptions about other people. Our brains create a story from what we notice about people and experiences. What did you see that made you perceive that the person is friendly or unfriendly? What did you see that made you think the person is someone you would like to get to know or not? What did you see that made you perceive that this person is wealthy or not? These are the facts that you used to create your perceptions. As a leader, it is critical to distinguish between the facts of a situation versus the stories you have formed to make sense of the facts.

It is easier to see how we create perceptions with strangers. We constantly develop stories and perceptions about the people we know in our social systems. We are frequently, subconsciously, creating stories about our experiences all day long. Even our physical feelings of warmth and coldness can influence our perceptions of others as warm (e.g., trustworthy, generous, and caring) or cold (Williams & Bargh, 2008).

Perceptions: Friend or Foe

Our perceptions (i.e., the meaning and understanding we create from incoming data) are being formed all the time, both helping and hurting us. We use perceptions to help us navigate a world full of billions of bits of sensory data. If we were conscious of all the sensory data, our brains would become overwhelmed and make it challenging to navigate the world. We often refer to this as “sensory overload.” We can shut down when there is too much data coming in too fast to make sense of it. Even our neural system filters out some sensory information or handles it unconsciously to go about our day with fewer moments of sensory overload.

Our perceptions create challenges because we build our perceptions on limited facts. Our perceptions are our interpretations of the facts (i.e., the story we make about the facts). We fill in gaps in the data with likely guesses based on prior experiences. We can use movies to explore how we create meaning about facts and how others create different understandings about the same set of facts. When two people watch the same movie, they will create different perceptions about the information they saw during the movie. They will have different perceptions of the characters and overall film. Sometimes the perceptions are similar, and sometimes the perceptions are very different.

QUESTIONS FOR JOURNALING & REFLECTION

Prompt 1: List at least five things that you think often cause two people to create different perceptions after watching the same movie.

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

When you watch a movie a second and third time, you often “see” new information that you missed the first time. Seeing new information may cause you to revise your perceptions of the characters in the movie. You might even realize that your first perceptions were wrong because you missed some vital information or misinterpreted the facts.

We take in millions of data points every second. However, scientists estimate that our conscious minds can only process a limited amount of data at a time:

The amount of domain-specific information that the brain can process during a certain period of time has an estimated capacity ranging from 2 to 60 bits per second (bps) for attention, decision-making, perception, motion, and language, and up to 106 bps for sensory processing. However, the conscious mind can only handle a portion of higher-order information at a time. (Wu et al., 2016, p.1)

That means that we are processing millions of data points without even knowing it, unconsciously creating a perception story. We continuously develop stories about facts, which can become problematic when we are not aware that the stories are not facts but merely stories about facts.

The same process happens in real life. Two people can be in a team meeting and have very different perceptions about the facts of the meeting. We gather and organize information about people and conversations during the meeting, just like we do when watching a movie. Like watching movies with family or friends, team members often have different perceptions after attending the same team meeting.

Prompt 2: Think about a team meeting or class you recently experienced where you had different perceptions than your teammates about how it went. List three things that you think caused you to select different data, organize it, and create different interpretations than your teammates.

Let’s watch a quick video called The Monkey Business Illusion: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IGQmdoK_ZfY.

As we discussed earlier, when people watch the same movie, they often create different perceptions. Team members attend a team meeting and can have different perceptions of what happened. People notice different information, thus seeing things differently. What you choose to focus on influences the perceptions you create. In the Monkey Business Illusion video, the narrator said to focus on people in white shirts, which may have led you to miss important information (e.g., curtains changing color). Another example would be to imagine two people going separately into a dark room with a flashlight. After you both go into the room, you share what you saw. Where you chose to shine your flashlight guided your attention and determined your perception of the space.

In the Monkey Business Illusion video, the narrator said to focus on the people in the white shirts, which is called priming. Priming is when something influences or guides what you notice or how you respond to a situation (Priming, n.d.). In the dark room example, priming would be if someone told you to look in all the room corners. You would likely move from corner to corner with your flashlight and possibly not shine the light in the middle of the room.

When you are sitting in a meeting or interacting with someone, what is guiding your perception? What is directing your attention like a flashlight? What is driving which information you are choosing to gather and what information you might unknowingly leave out? You may not have noticed the orange curtains in the video because the narrator said to focus on the people with white shirts. Your eyes saw the color change, but it did not make it into your conscious field because you did not think it was essential to the outcome.

The same thing happens when you interact with others. Your attention is like a flashlight. You notice some things about the person and what they are sharing, and some things do not make it into your conscious field because it is not crucial to the goal as perceived by you. What you choose to notice about a person impacts your relationship with that person. What was your perception of their body language? Did you see who was sharing ideas and who was not sharing ideas?

Prompt 3: Think about a time when you created a perception about a team meeting that later turned out to be wrong.

- What influenced the perception you initially created about the meeting?

- What caused you to change your perception of the meeting?

- What lesson can you take away from that experience of changing your perceptions?

Key Influencers when Creating Perceptions

We know that we constantly create perceptions and stories about people and experiences. We make these stories from small amounts of data in our conscious and unconscious minds. You were told or primed to notice a specific thing in the Monkey Business Illusion and dark room examples. What is directing our attention if there is no one externally telling us where to focus our attention? You! You are choosing—usually unconsciously—what to notice.

A few critical things guide our focus. Our prior experiences and emotions over time crystallize into our values. Our previous experiences and feelings impact what data we select from the entire data field and how we interpret data to form our mini-stories. Understanding how our values act as lenses to determine and analyze information is essential.

In Chapter 2, you identified and discussed your values. Your values act as filters when creating perceptions. Imagine having glasses that made everything look red while someone else had glasses that made everything look green. Your glasses would impact your perceptions. Our values act as similar filters. Having a value of liberty will lead us to different perceptions of an experience than having a value of care. These values are not right or wrong but lead us to possible different perceptions, judgments, and actions as leaders.

You are subconsciously choosing not to bring some information into your consciousness. Some of what does not make it into your conscious awareness may be significant. As Saleem Usmani (2019) points out in his TEDx talk, we make about 35,000 decisions a day (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MtJhRMfLBCg). If you fail to notice that you are excluding some people in team meetings, it may impact your effectiveness as a leader. Since we are all not noticing important things, collaboration becomes critical to create a collective focus. You need more flashlights in the room to see more of the room. Seeing more of the room will help you make better decisions, creating sustainable social change.

“The range of what we think and do is limited by what we fail to notice. Moreover, because we fail to see what we have been unable to notice, there is little we can do to change; until we notice how failing to notice shapes our thoughts and deeds.” —R. D. Laing, psychiatrist

Summary

Humans are natural storytellers. We create stories about our experiences. These stories or perceptions help us make sense of our place in the world. It is essential to be aware of your perceptions, especially since they are often incomplete and created by subjective interpretation of the facts of an experience. Being aware of our faulty perceptions is critical when working with others to create social change. Leaders must be mindful of the perceptions they have of others, situations, and how they are contributing to the perceptions of others.

ACTIVITIES

Reflecting on Experiences

“We do not learn from experience … we learn from reflecting on experience.”—John Dewey, American philosopher, psychologist, and educational reformer whose ideas have been influential in education and social reform

Directions: Below are a few activities to help you become more aware of your perceptions and how you are creating them. Keep a journal of your perceptions after team meetings. Track how your perceptions change over time with the introduction of new data.

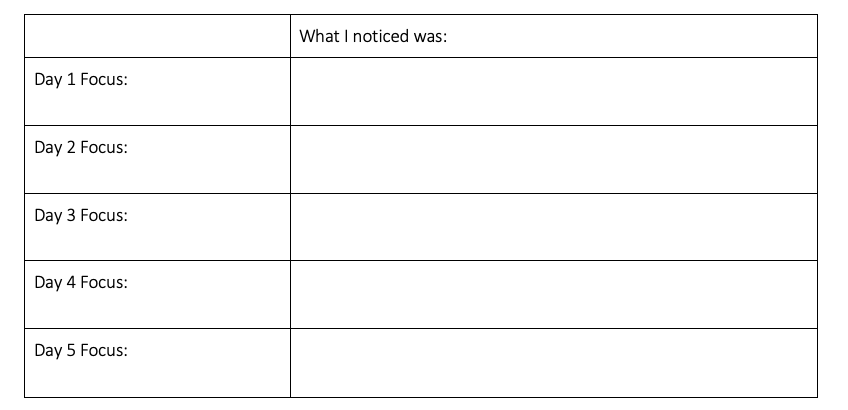

Noticing Challenge

Directions: Choose something different to notice each day for five days in a row. Keep a journal about the experience. To go deeper, watch the video Mindfulness Over Matter by Ellen Langer (22 min.): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4XQUJR4uIGM.

Movie Time

Directions: Watch a movie with friends. At the end of the film, ask them about their movie perceptions. Take it a step deeper and ask them what led them to those perceptions. What did they consciously notice that led to their perceptions? What may have unconsciously led to their perceptions (feelings, intuition, unconscious data, etc.)? Record notes following your discussion.

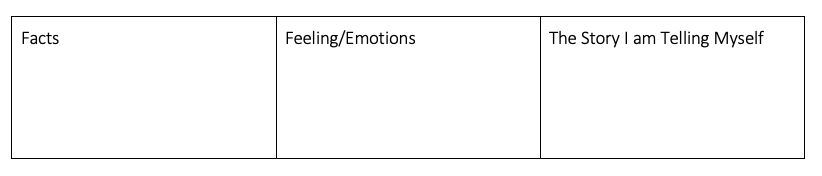

The Story I am Telling Myself

We treat our perceptions as facts rather than as stories we have created about the facts. Create three columns on a sheet of paper, as shown below. Label the first column “Facts,” the second column “Feeling/Emotions,” and the third column “The Story I am Telling Myself”—your perceptions. Write down the facts of what happened in the column labeled Facts. Write down your feelings and emotions in the second column. Write down the story you have created using the facts in the column labeled The Story I am Telling Myself.

Perception Check Partner

Directions: It is harder to be conscious of creating perceptions in real time. Use a partner to do a perception check. If you have similar values and experiences, your perceptions may be more alike. It is better to compare your perceptions with several individuals. You can do this during or after a meeting. Add a perception check to the meeting agenda. Stop halfway through a meeting and ask team members their perceptions about how the meeting is going and what is influencing those perceptions.

Ladder of Inference

Directions: The ladder of inference is a visual tool to help us be conscious of creating perceptions or conclusions. We select data from a pool of data, apply assumptions, and filter it through our beliefs to arrive at findings that inform our actions as leaders. Read and reflect on the following article, then view the video. Journal about or reflect on what you learned from these.

Article: The Ladder of Inference: Why we jump to conclusions (and how to avoid it)

More Resources for Perception Checking

“That is one story I could tell. What is another story I could tell?” (attributed to Kem Gambrell, assistant professor at Gonzaga University)

Directions: In Unlocking Leadership Mindtraps, Jenifer Garvey Berger (2019) recommends creating multiple stories using the same set of facts. Creating numerous stories helps us create multiple perceptions; this helps us realize that our perceptions are not unilateral truths. To go even further, she asks leaders to create a story using the same set of facts except with someone else as the heroine or hero in the story. Jennifer Garvey Berger reviews the five mindtraps in the video “Meet the Mindtraps,” (https://youtu.be/S0-79bd6B2s). Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie discusses the danger of a single story or perception in her TEDx talk, “The Danger of a Single Story,” https://www.ted.com/talks/chimamanda_ngozi_adichie_the_danger_of_a_single_story

REFERENCES

Berger, J. G. (2019). Unlocking leadership mindtraps: How to thrive in complexity. Stanford Briefs.

Komives, S. R., Owen, J. E., Longerbeam, S. D., Mainella, F. C., & Osteen, L. (2005). Developing a leadership identity: A grounded theory. Journal of College Student Development, 46(6), 593–611. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2005.0061

Komives, S. R., Longerbeam, S. D., Owen, J. E., Mainella, F. C., & Osteen, L. (2006). A leadership identity model: Applications from a grounded theory. Journal of College Student Development, 47(4), 401–418. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2006.0048

Higher Education Research Institute. (1996). A Social Change Model of Leadership Development (Version III). UCLA. https://www.heri.ucla.edu/PDFs/pubs/ASocialChangeModelofLeadershipDevelopment.pdf

Langer, E. J. (2013). Ellen Langer: Mindfulness over matter [Video].YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4XQUJR4uIGM

Langer, E. J. (2014). Mindfulness (25th anniversary edition). Da Capo Press.

Priming. (n.d.). Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/basics/priming

Schacter, D. L., Gilbert, D. T., & Wegner, D. M. (2011). Psychology (2nd ed). Worth Publishers.

Simmons, D. (2010). The monkey business illusion [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IGQmdoK_ZfY

Usmani, S. (2019). Perception vs. reality | Saleem Usmani | TEDxMacatawa [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MtJhRMfLBCg

Williams, L. E., & Bargh, J. A. (2008). Experiencing physical warmth promotes interpersonal warmth. Science, 322(5901), 606–607. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1162548

Wu, T., Dufford, A. J., Mackie, M.-A., Egan, L. J., & Fan, J. (2016). The capacity of cognitive control estimated from a perceptual decision making task. Scientific Reports, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep34025