Ancient Egyptian Art

Introduction

It has been claimed that the ancient Egyptians had no word for “art.” That’s true to an extent – although the word hemut’ is, depending on the context, translated as either ‘art’ or ‘craft.’ Instead, the Egyptians possessed a sense of aesthetic, within a function. That is – art served a purpose, almost always religious in nature (PBS, 2006; RCS, 2022). The ancient Egyptians did not have a conception of “art for art’s sake,” though they did develop and refine an aesthetic tradition over the nearly 28 centuries of Egyptian history between the unification of Upper and Lower Egypt c. 3100 B.C.E. until the conquest of Egypt by Alexander the Great in 332 B.C.E.

Religion permeated every aspect of Ancient Egyptian life. Their literature, philosophy and religious scholarship detailed a rich mythology describing some 1,500 known deities. Some of their names may already be familiar to you: Ra, Osiris, Isis, Set. The Pharaohs, were considered to be, variously, descended from the gods, appointed by the gods, or the earthly embodiment of the gods (Hart, 2006). If you find the variation confusing, remember that we’re talking about 2,800 years of cultural and religious history here — a longer period of time than that which has elapsed since.

Pharaohs were particularly associated with Horus, as they were considered to be Horus’ earthly embodiment. Most commonly, the Pharaohs were seen as divinely appointed intermediaries. Thus, religion and government were, philosophically, one and the same. Religion was also huge part of the ancient Egyptian economy. The ancient Egyptians built thousands of temples throughout their empire. The largest temples employed thousands of people apiece, including priests, artisans and laborers (Wilkinson, 2000).

These temples are one of the major sources of surviving art: a massive collection of painted murals, carved stone reliefs, statues and pottery. Another, of course, is from their elaborate burial rituals, including highly decorated sarcophagi, burial chambers, and the attentively-preserved bodies of the deceased. Egyptians stocked the tombs of the dead with objects they would need in the afterlife. And, thanks to the dry climate of Egypt, an astounding amount of ancient artifacts survived to present day, giving us uniquely detailed insights into their culture and civilization, including food stuffs, papyrus texts, textiles, toys and board games.

Around the same time as ancient Sumerians were developing cuneiform, the ancient Egyptians were developing, independently, their own form of writing: hieroglyphics. And, similarly, this innovation allowed for the development of math, geometry and engineering. Easily the most iconic of these are the pyramids. The Great Pyramid of Giza, built c. 2,600 B.C.E., was the tallest structure in the world for 3,800 years until the 1311 construction of Lincoln Cathedral in England. Building such monuments required the existence of a stable, prosperous society. The Great Pyramid took 27 years to build and contains 2.3 million blocks, each of which weighs about two and a half tons. And, thanks to recent archeological work, it is now known that they weren’t’ built by slaves but by skilled, paid workers (Shaw, 2003). Ten to forty thousand of them, living in a special city custom built for the occasion. One estimate puts the cost of the Great Pyramid, if we wanted to build one today, at around $5 billion. By way of comparison, One World Trade Center in New York cost a little less than $4 billion, and remains the most expensive single building in the United States.

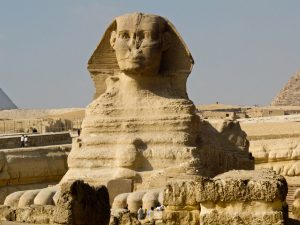

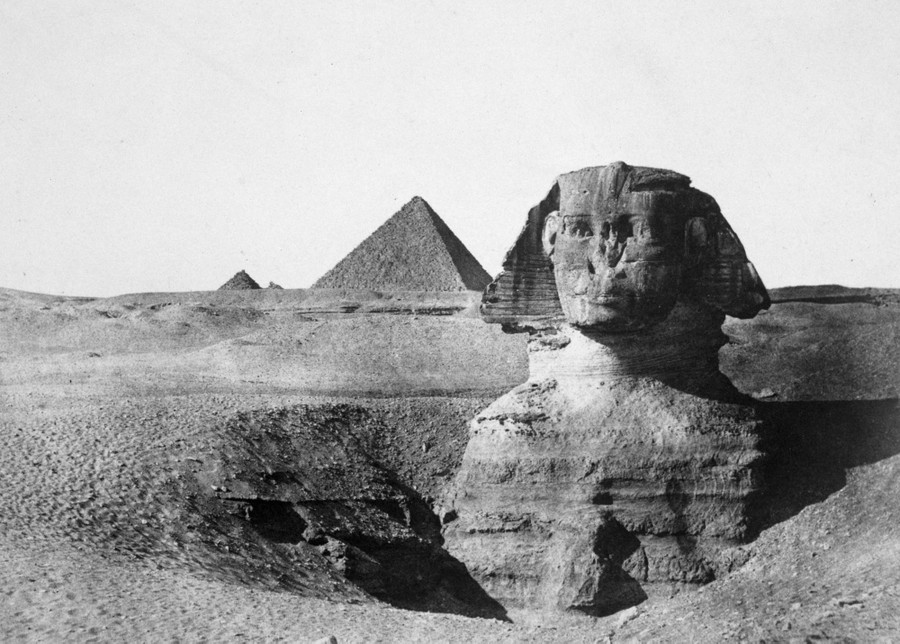

Looking at Egyptian history requires one to describe large spans of time in broad strokes. Twenty eight centuries is a timespan 11 times greater than the current age of the United States. Ancient Egypt was already ancient by the time the Roman Empire reached its height. To understand just how ancient consider this: the first complete excavation of the Great Sphinx of Giza was carried out during the reign of Roman Emperor Nero, during the first century C.E. The Romans built a viewing platform and a stairway to access the site, as well as undertook conservation efforts at the site, which became a popular tourist destination (Hawass, 1998).

Yes, 2,000 years ago the Sphinx was already sufficiently ancient and mysterious to warrant a conservation effort and install facilities for tourists who wanted to travel to see this great figure rising out of the sand. In fact, more time had elapsed between the construction of the Sphinx and the Roman excavation of it than has elapsed *since.* That’s a lot of history to cover in one module, feel free to visit the additional reading links if you find your interest piqued.

So, with all this in mind, let’s start learning about the history of ancient Egypt, its culture, its people, and its art. Or, rather, hemut’.

Virtual tours

Interested in taking a virtual tour of some Egyptian heritage sites? Visit these links to visit!

Tour of the Tomb of Meresankh III. Meresank III was married to King Khafre, during whose reign was built the Pyramid of Khafre, the second-tallest ancient Egyptian pyramid and, probably, the Sphinx.

Menna was an official who held positions in both temple and palace administration. He was both a scribe and an agricultural overseer.

Depictions of the Sphinx through the ages

For a gallery of historical photos of the Sphinx from The Atlantic please visit this link.

Sources:

Hart, G. (2006). A dictionary of Egyptian gods and goddesses. Routledge.

Shaw, J. (2003). Who Built the Pyramids?. Harvard Magazine, 6, 42-99.