Objectives:

After reading and studying the contents of this chapter, the student will:

- Understand the objectives/outcomes/competencies for the “searching” lectures and labs

- Understand and be able to explain the differences between ‘talking’ to computers and talking to humans

- Know the names of the two approaches to searching and their pros and cons.

- Know when keyword searches are essential

- Know how to limit a PubMed search to items that haven’t been indexed yet

_________________________________________________________________________________

Objective 1.

Understand the objectives of the “searching” lectures and labs

The second quarter of Introduction to Drug Information is focused on teaching you the skills needed to conduct a comprehensive PubMed search, a search for all the evidence included in PubMed.

You will need to use comprehensive search techniques at least twice, and probably more often, in the future:

- when you work on the final search assignment for this class,

- when you work on your group project for Drug Literature Evaluation and Research Methods during your P3 year.

- if, as a pharmacist, you work on a literature reviews to support formulary decisions

- if you co-author a systematic review, meta-analysis, or practice guideline

A few important definitions:

A Formulary is the list of drugs that a pharmacy offers.

Formulary decisions are decisions concerning whether a pharmacy should offer a particular drug.

Reviews are journal articles, web-based articles, book-based articles, or other reports that summarize the previously published evidence on a specific issue.

A Systematic review is one type of review article. A well-performed systematic review is the highest form of evidence (further details below).

Systematic Reviews

Well-written systematic reviews are considered the highest form of evidence. ⭐ A systematic review:

- is based on exhaustive searches,⭐ searches that attempt to identify all the available evidence. (These searches are complex searches worthy of a research librarian or drug information specialist. This is the type of search you will complete for the final search assignment for this class.)

- is based on searches of several databases.

- You will focus on learning how to search one database, PubMed, during this course.

- Later, if you want to write a systematic review for publication in a journal, you (or your information specialist/librarian collaborator) will need to search several databases. For example, you might search PubMed (or another version of MEDLINE), EMBASE, The Cochrane Library, and Scopus. Each of these databases either indexes the literature in a different way or includes records for articles not included in the other databases.

- includes a copy of the search strategies used. (The strategies are included so that others can replicate and test the quality of the search work).

- evaluates the quality of all articles that remain after inclusion and exclusion criteria are applied to the search results.

- integrates the results of articles of adequate quality to produce overall recommendations for practice and/or research.

- may include re-analysis of the combined data from the studies that remain after application of inclusion and exclusion criteria. When such combined data analyses are conducted, the systematic review is also a meta-analysis.

Not all searches require comprehensive/exhaustive search efforts

You will be learning techniques needed to conduct a comprehensive search, but I don’t want you to think that every search deserves this level of effort. Sometimes you need a few articles as sources for a class assignment or a single article to use for a journal club. In these situations, a quick search containing one keyword, or perhaps a few keywords, for each of your search concepts may be all that is needed. You may even want to require that the keywords be found in the article title. Many of the mid-term exam questions will focus on creating and troubleshooting such simple searches.

_________________________________________________________________________________

Objective 2.

Understand and be able to explain the differences between talking to computers and talking to humans

A couple of exercises to introduce this topic

Exercise 1.

Let’s pretend you are asked to create a file of images of red socks. Here are some images:

| image description | image | image source |

|---|---|---|

| a. red sock |  |

(Pikrepo. Unpaired red sock, free for commercial use, https://www.pikrepo.com/ftdzh/unpaired-red-sock) |

| b. Christmas snowflake socks |  |

(Pxfuel. free for commercial use, https://www.pxfuel.com/en/free-photo-icjhe) |

| c. tomato sock |  |

(Pxfuel, free for commercial use, https://www.pxfuel.com/en/free-photo-efkht) |

| d. burgundy socks |  |

(Pxfuel, free for commercial use, https://www.pxfuel.com/en/free-photo-xnrue) |

| e. all of the above | ||

| f. none of the above

|

Exercise 2.

You ask a computer to search for “red socks” images. Here are the image descriptions you let the computer search:

| image description | image | image source |

|---|---|---|

| a. red sock |  |

(Pikrepo. Unpaired red sock, free for commercial use, https://www.pikrepo.com/ftdzh/unpaired-red-sock) |

| b. Christmas snowflake socks |  |

(Pxfuel. free for commercial use, https://www.pxfuel.com/en/free-photo-icjhe) |

| c. tomato sock |  |

(Pxfuel, free for commercial use, https://www.pxfuel.com/en/free-photo-efkht) |

| d. burgundy socks |  |

(Pxfuel, free for commercial use, https://www.pxfuel.com/en/free-photo-xnrue) |

| e. all of the above | ||

| f. none of the above

|

A. When humans are asked to search for items meeting certain criteria. They hear the criteria and automatically browse for items containing the criteria concept.

Most students answer “all of the above” to exercise 1.

B. Computers can only be counted on to look for the exact characters/letters you enter in the search box.⭐

A computer asked to find “red socks” would not find any of the image descriptions listed in exercise 2 (answer f).

A computer will not automatically search for the plural version of a word when you enter the singular version.

Example: Compare the number of results retrieved when you search PubMed for:

-

-

-

-

-

- sock

- socks

- sock OR socks

-

-

-

-

Computers don’t automatically search for British as well as American spellings

Example: Compare the number of results retrieved when you search PubMed using the following search strategies. These strategies were designed to retrieve articles containing American esophagus-related words (esophagus, esophageal, esophagectomy, etc.) or the comparable British oesophagus-related words:

-

-

-

-

-

- esophag*

- oesophag*

- esophag* OR oesophag*

-

-

-

-

Computers don’t automatically search for abbreviations, full generic names, brand names, and scientific names for drugs.

Examples: Compare the number of results retrieved when you search PubMed for:

-

-

-

-

-

- MMF

- “mycophenolate mofetil”

- Cellcept

- MMF OR “mycophenolate mofetil” OR Cellcept

-

-

-

-

C. What does this mean for the human who wants a computer to search in the same way he/she would?

The comprehensive searcher must include all sets of characters (all the terms) an author might have used to indicate that he/she is discussing a concept⭐

The searcher must join these terms in a language the computer will understand using:

OR, AND, NOT, ()

Example:

Instead of a search for —

“red socks”

— a searcher attempting a comprehensive search might search for —

(hosiery OR hose OR sock OR socks OR anklet OR anklets) AND ( red OR magenta OR cranberry OR cherry OR burgundy OR tomato OR crimson )

Google no longer shows the number of results retrieved by a search. However, when Google was showing result numbers, the —

“red socks”

— search produces over 1 million results. The great majority were relevant.

The more exhaustive search —

(hosiery OR hose OR sock OR socks OR anklet OR anklets) AND ( red OR magenta OR cranberry OR cherry OR burgundy OR tomato OR crimson )

— retrieved over 1 billion Google results. Some relevant results were retrieved that had not been retrieved by the first search. Like the result below:

However, the more exhaustive search also retrieved a lot of unexpected irrelevant results like many links to articles about the red garden or fire hoses.

D. Unfortunately, as in the example just given, techniques that will help you find all the relevant records will also force you to look through irrelevant records.⭐

One must work on the search to make the number of irrelevant results tolerable.

To make sense of the next part of this chapter, you need to be aware of the type of content that is searched when you search Google, Google Scholar and PubMed.

The Google and Google Scholar search engines ‘look through’ all the text accessible to the search engine. This usually includes:

- all the article citation information (authors’ names and affiliations, the article and journal titles, the volume, issue and doi numbers),

- the abstract,

- the text of the entire article,

- and the reference list.

Unfortunately, the contents of sidebars (which sometimes link to articles on totally different topics) are searched also.

PubMed records (like records in most standard literature databases) do not include the article’s full-text, so the PubMed search engine searches:

- all the article citation information (authors’ names and affiliations, the article and journal titles, the volume, issue and doi numbers),

- and the abstract

Some PubMed records, the MEDLINE records, include subject headings. Most standard literature databases have a subject headings system in which each concept is indicated by a single term . The presence of subject headings allow the searcher to use one term for a search when authors may use several different terms or even hundreds of terms for that concept. Think of all the terms used for cancer (cancer, carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, malignancy, neoplasm, leukemia, lymphoma, sarcoma, etc., etc.). There is a single heading in MeSH which will find all the cancer articles.

Indexing and Subject headings are foreign concepts to many students. To really understand indexing and medical subject headings (MeSH), you need to know a little about the ‘life cycle’ of a PubMed record:

- Publishers create the PubMed records for the articles in their MEDLINE-indexed journals. The publisher logs into the administrative side of PubMed and enters information for their article. The information they enter includes the article’s citation information (including authors’ names, article and journal titles, volume and page numbers, and publication date), abstract, authors’ affiliations, and language of the publication.⭐

- A combination of computer- and human-performed indexing follows. A computer and/or a human paid by the National Library of Medicine ‘reads’ the full-text article.

- The computer or indexer picks headings corresponding to the article’s topics from the MeSH subject heading list (also called the MeSH thesaurus or MeSH database) and adds these headings to the article’s record.⭐

- The computer and/or indexer also selects ‘tags’ or medical subject headings that indicate the article type (review, editorial, randomized controlled trial, etc.), whether humans or other animals are discussed, and the age and sex of the humans discussed (if humans are discussed and age or sex are important)⭐

- When the indexing process is complete the record becomes a fully-indexed MEDLINE record. Since the advent of computer indexing, indexing for MEDLINE is essentially instantaneous. However, human indexers may revise the work done by computer indexing.

E. Computerized search engines may use algorithms that either focus your search or add terms to your search strategy

- Google uses knowledge about the results favored by you and other searchers to narrow the focus of your search or to rank the results of your search. (Details about Google’s techniques for narrowing searches and ranking search results are not available to the public.)

- PubMed “maps” keyword searches to include additional, generally useful, terms in a search. These terms may include relevant medical subject headings (MeSH) and/or additional relevant keywords.

- MeSH (medical subject headigns) are the indexing terms are used to indicate the topics covered by a journal article indexed in MEDLINE.

-

- Keywords are just words for a concept, words an author might have used in the title or abstract or assigned to their article to indicate the topic of that article. Of course, these are also words a searcher might use if trying to identify articles by searching the articles’ titles and abstracts. ⭐

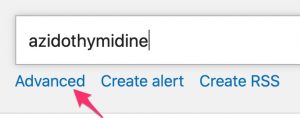

Follow the steps below to see how PubMed maps some sample keywords.

-

- Go to www.pubmed.gov (you don’t need to see full-text from UNMC for this exercise)

- search for —

azidothymidine

(azidothymidine is the scientific name of the first drug used extensively to treat HIV).

-

- Click the “Advanced” link under the PubMed search box.

-

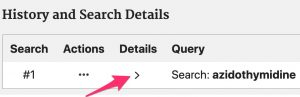

- Find the “History and Search Details” table.

-

- Click on the “>” in the “Details” column.

-

- In the “Query” column under “Translations,” you can see that azidothymidine has been translated into:

- the supplementary concept “zidovudine”[Supplementary Concept]. (Zidovudine is the generic name for azidothymidine. ) Supplementary Concepts are similar to MeSH terms. They are usually used when it becomes necessary to index a concept and no term for that concept is present in the MeSH thesaurus/browser/database It takes awhile for new concepts to be added to the official MeSH vocabulary.

- the medical subject heading(MeSH) “zidovudine”[MeSH Terms].

- the keyword zidovudine (“zidovudine”[allfields] )

- the keyword azidothymidine (“azidothymidine”[all fields] , this is the term you entered)

- In the “Query” column under “Translations,” you can see that azidothymidine has been translated into:

Follow the same steps for one or more of the terms below to determine how these terms are mapped by PubMed. You can enter search terms in the “Query box” on the “Advanced” page or in the search box on the PubMed results page.

1. Searching for monkeys will create a search for _______________

2. searching for SJS (a common abbreviation for Stevens-Johnson Syndrome) will create a search for SJS or ____________

3. searching for PD (a common abbreviation for Parkinson’s Disease) will create a search for PD or _____________

F. What if you don’t like a PubMed translation?

Any of the following will stop translation in PubMed:.

-

- enclose the term in quotes, e.g. “SJS”

- truncate the term, e.g. monkey*

- The asterisk wildcard is used after a word trunk. It represents either no additional letters or any combination of additional letters. A search for — monkey* — will retrieve records containing any of the following words: monkey, monkeys, monkeying, monkeywrench.

- In PubMed, as in most standard literature databases, truncation can only be used at the end of a search term or search phrase. Colo*r will not work. “Parkinson* Disease” will not work

- add a field tag that limits the search to particular part/s of the record.

For example, the [tiab] tag as in —

PD[tiab]

— limits the use of a search term to searching the title and abstract.

| Affiliation [AD]

Article Identifier [AID] All Fields [ALL] Author [AU] Author Identifier [AUID] Book [book] Comment Corrections Corporate Author [CN] Create Date [CRDT] Completion Date [DCOM] Conflict of Interest [COIS] EC/RN Number [RN] Editor [ED] Entrez Date [EDAT] Filter [FILTER] First Author Name [1AU] Full Author Name [FAU] |

Full Investigator Name [FIR]

Grant Number [GR] Investigator [IR] ISBN [ISBN] Issue [IP] Journal [TA] Language [LA] Last Author [LASTAU] Location ID [LID] MeSH Date [MHDA] MeSH Major Topic [MAJR] MeSH Subheadings [SH] MeSH Terms [MH] Modification Date [LR] NLM Unique ID [JID] Other Term [OT] Owner Pagination [PG] |

Personal Name as Subject [PS]

Pharmacological Action [PA] Place of Publication [PL] PMID [PMID] Publisher [PUBN] Publication Date [DP] Publication Type [PT] Secondary Source ID [SI] Subset [SB] Supplementary Concept[NM] Text Words [TW] Title [TI] Title/Abstract [TIAB] Transliterated Title [TT] UID [PMID] Version Volume [VI] |

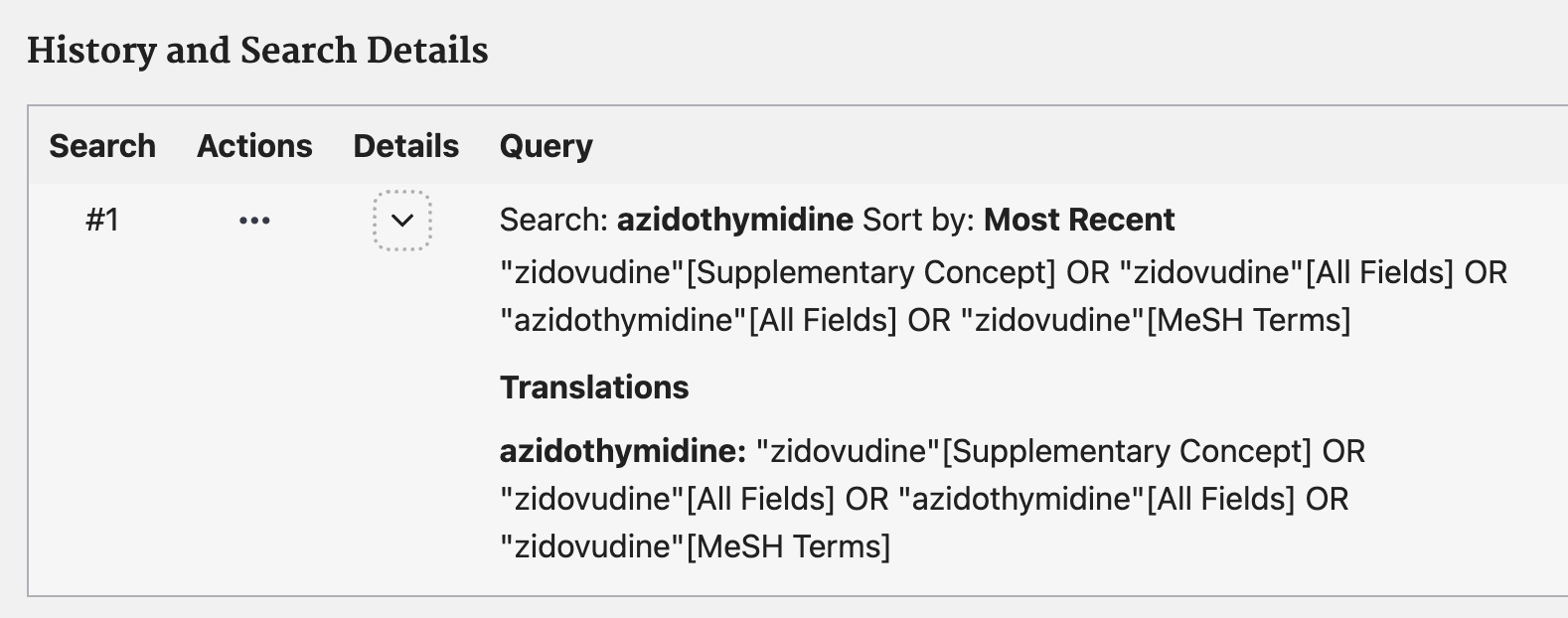

You will need the title [ti], title/abstract [tiab], and all fields [all] tags most often, but you do not have to have the table above or remember the field tags to use them. The “Advanced” page in PubMed includes an “Add terms to the query box” search box with an adjacent field selection drop-down menu.

Give this feature of the “Advanced” search page a try.

- If you are not already looking at the “Advanced” search page, go to PubMed’s “Advanced” search page using the “Advanced” link under the PubMed search box

- After you reach the “Advanced” search page, find the “Add terms to the query box” area of the page . (If you are looking at a “translation,” scroll up to see the “Add terms to the query box” area.)

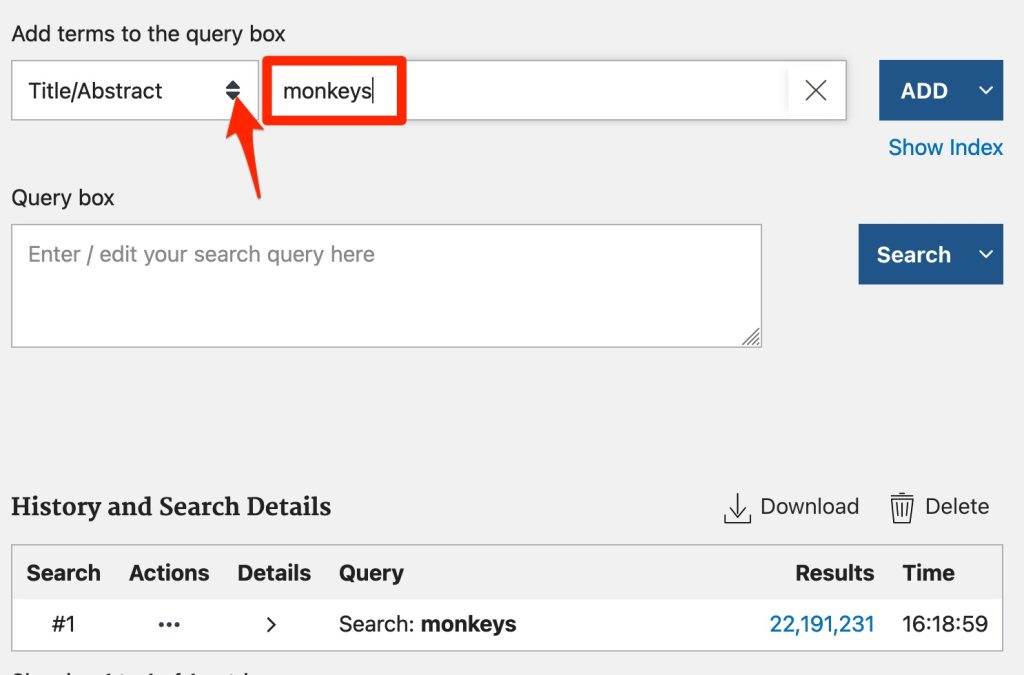

- Type monkeys in the “Add terms to the query box” search box.

- Select the “Title/Abstract” field from the drop-down to the left of the search box.

- Click the “Add” button

- You should now see — monkeys[Title/Abstract] — in the “Query box” (as shown in the screenshot below).

![A screenshot showing the monkeys[title/abstract] search in the "Query" box.](https://pressbooks.nebraska.edu/app/uploads/sites/77/2020/06/tag-added-1024x389.jpg)

- Click the “Search” button. Look at the number of results.

- If you don’t remember the number of results retrieved without the [Title/Abstract] tag, return to the “Advanced” search page and scroll down to the “History and Search Details” table.

![A screenshot points out the differences between the -- monkeys -- and the -- monkeys[title/abstract] -- searches.](https://pressbooks.nebraska.edu/app/uploads/sites/77/2020/06/compare-result-numbers-1024x284.jpg)

_________________________________________________________________________________

Objective 3. Know the names of the two approaches to searching and their pros and cons.

A. Virtually all search engines can be searched using keywords (author words) .

- Pros of keyword searching :

- Virtually all databases and search engines (including Google, MedlinePlus, Clinicaltrials.gov, journal search engines, MEDLINE, PubMed Central, and many other important resources) can be searched with keywords.

- The steps in basic keyword searching are not search-engine-specific.

- Cons

- Producing a comprehensive keyword search is hard work. Synonyms for search concepts must be included.

- Some search engines don’t allow for use of certain search tools.

e.g. You can’t truncate with asterisks (*) in Google or Yahoo⭐

-

- You may retrieve irrelevant records.

If you search with the term “leukemia” (a medical term for blood cancer), you will retrieve records for articles about leukemia, but will also retrieve records containing sentences like:

-

-

- “future work should focus on leukemia”

- “we will discuss every form of cancer except leukemia”

-

B. Many literature databases have very useful subject heading systems that can be used in searches.

A “subject heading” review:

Typically, each article that has a record in the database is read by one of the database’s indexers or scanned by an indexing computer. The indexer adds:

- Publication types headings/tags

- Subject headings (MeSH) for the topics that receive significant attention.

- Subject headings for genders discussed, age ranges discussed, species discussed (humans vs. animals)

- Substance terms/supplementary concepts (headings for things that don’t have official headings yet).

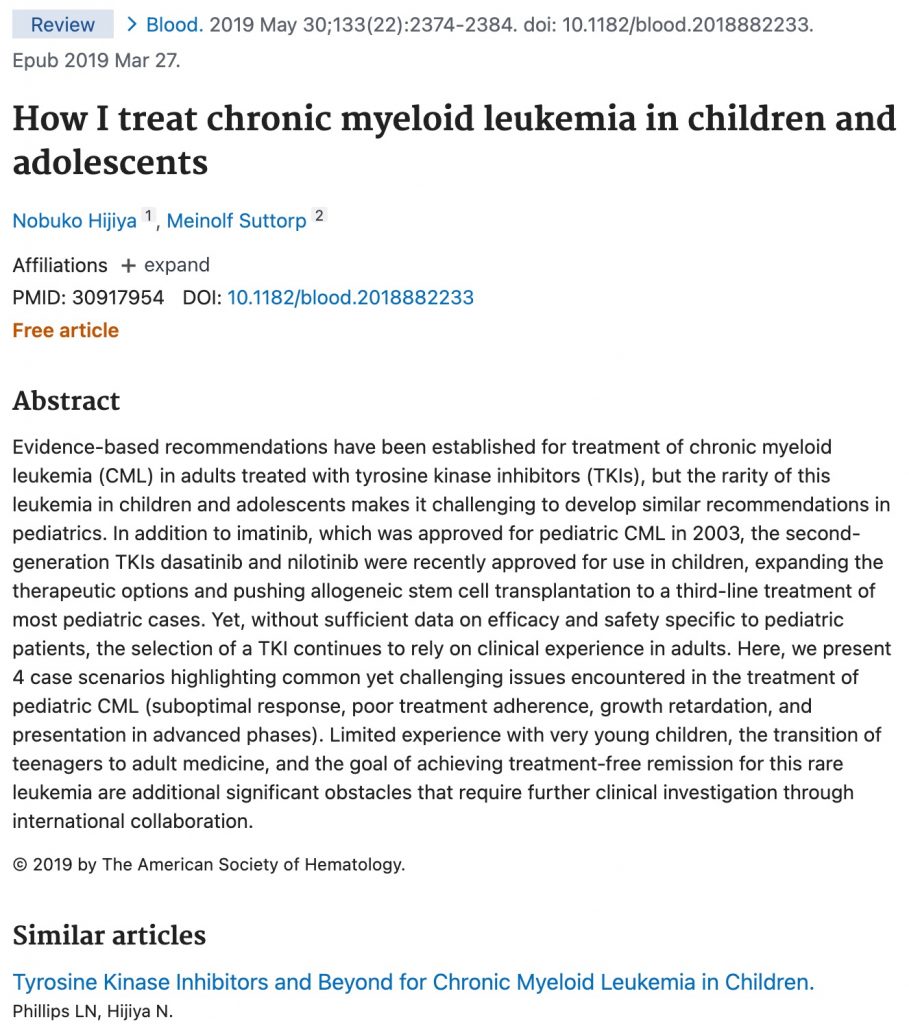

A sample MEDLINE record.

In the sample MEDLINE record below, the publication type, subject headings, and substance terms added by the indexer are inside the red square:

….

Keyword searches search the whole record and search all records in PubMed.

Subject headings only search the “Publication types,” “MeSH Terms,” and “Substances” portions of the record. This section is not present in all PubMed datasets.⭐

- This section is present in MEDLINE records (MEDLINE records are fully indexed).

- This “section isn’t present in PubMed’s other dataset, non-MEDLINE PubMed Central.

- PubMed contains records for articles in PubMed Central (a full-text repository). Some of these articles have been published in journals that are not indexed for MEDLINE. These articles will never be indexed.

Pros and Cons of Medical Subject Heading Searching

- Pros

- There is a single MeSH term for a concept (For example, regardless of whether an author uses the term ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or Lou Gehrig’s disease; the article is indexed with the heading “Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis”)

- MeSH searches are relatively easy to construct.

- Heading/subheading combinations can be used to focus a search on an aspect of a topic (For example, the heading/subheading combination “Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis/therapy”[mesh] will focus your search on articles about ALS therapy rather than articles about ALS diagnosis OR ALS epidemiology.)

- Cons

- not all articles are indexed with subject headings. If a search requires the presence of a heading, it will not retrieve any unindexed records.

_________________________________________________________________________________

Objective 4. Know when keyword searches are essential.

Keyword searches are essential:

1. Keyword searches are essential when searching multiple databases simultaneously. Different databases have different subject heading systems.

2. Keyword searches are essential when searching a database with a poorly organized or poorly applied subject heading system. This is unusual. IPA (International Pharmaceutical Database) is an example of a database with a nearly worthless subject heading system.

3. Keyword searches are essential when searching systems/databases without subject headings systems — ex. internet (Google Scholar, Google, Bing, Yahoo, etc.), Scopus

4. Keyword searches are essential when searching for records that are awaiting indexing and when searching for articles that will never be indexed. (With the advent of computer-indexing, an ever decreasing number of databases contain records that are awaiting indexing.)

In PubMed, records that will never be indexed are called non-MEDLINE PMC records. non-MEDLINE PMC records are PubMed records for items in PubMed Central (a full-text repository) that have not been published in MEDLINE-indexed journals⭐.

A few words about the full-text included in PubMed Central and represented by PMC records:

- PubMed Central was created as a repository for the full-text versions of articles that resulted from research funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) ⭐. It was a way to give US citizens free access to the work their tax dollars had funded. US law now requires that NIH-funded work bankrolled by grants awarded in Oct. 2007 or later must be added to PMC.

- Some of the NIH-funded PMC articles are published in journals that are indexed in MEDLINE records. Their PMC records are fully-indexed MEDLINE records.

- Some of the NIH-funded, PMC articles are published in high quality journals that just haven’t achieved inclusion in MEDLINE yet (there are many such journals). The records for these articles remain non-MEDLINE, PMC records.

- Occasionally, an NIH researcher is ‘tricked’ into publishing in a predatory journal. Predatory journals typically charge high publication fees and provide poor or no peer review, and, thus, publish articles of very uneven quality. A few predatory journals even sell authorships (they will add an author to a previously published paper for a payment without consent of the other authors). If NIH research has been published in such a journal, a non-MEDLINE, PMC record for that article will appear in PubMed. If you go on to publish articles in the journal literature, you will spend some time deciding where to publish your research. Remember, journals that have just a few records in PubMed may be untrustworthy.

- After PMC’s creation, some open access journals began to ask to deposit all of their articles in PMC. Journals (especially those produced by smaller publishers) want their open access content included in PubMed Central because it makes their journal content easier for researchers to find and cite, and, thus, makes the prospect of publishing in these journals more attractive to authors looking for homes for their manuscripts.

- Some of these journals were already indexed in MEDLINE (ex. Journal of the Medical Library Association – JMLA). These articles have corresponding MEDLINE records.

- Other journals asking to be included in PMC were not indexed in MEDLINE, and so a review process was created to try to keep journals with unethical practices or poor peer review out of PMC. The review process for inclusion in PubMed Central is fairly rigorous, but it is not as rigorous as the process that precedes acceptance into MEDLINE. The records for the articles added to PMC after this type of review remain non-MEDLINE/PMC records unless and until they apply for and are granted inclusion in MEDLINE.

*******************

Objective 5. Know how to limit a PubMed search to items that haven’t been indexed

To limit a search to unindexed PubMed records (non-MEDLINE PMC):

a. Perform a keyword search in PubMed.

b. ⭐ Add –

NOT MEDLINE[sb]

– to the end of the search. [sb] stands for subset.

c. Apply any desired language or publication date limits.⭐

d. Apply the “systematic review” limit if desired ⭐ (the “systematic review” filter, unlike the other article type filters, is actually a little search composed of headings, keywords and journal names).

Do not apply limits other than language, publication date or systematic review filters. All other limits/filters are dependent on the presence of information added by indexers and will remove all unindexed records.⭐

d. Run the search.

5. Keyword searches are essential when no subject heading is available for a specific search topic.

Example:

Try searching the MeSH database for — postnasal drainage

Are the headings retrieved relevant? (Read the definitions for the headings retrieved, if any.)

To see the subject headings used for a concept without an easily located MeSH:

-

- Go to PubMed

- Enter the concept word or quote-enclosed concept phrase followed by a [ti] tag (title tag). For examples, enter the following in the PubMed search box:

“postnasal drainage”[ti]

-

- Hit the “Search” button.

- Click on the title of a relevant article

- Scroll to the bottom of the relevant records to find the “MeSH Terms” section of the record (click “Expand” if necessary).

- Look for headings that are specific to the concept of interest. If you don’t find a heading that is specific for your concept, you will have to represent that one search concept with keywords even if the remaining concepts can be represented by MeSH.

6. Keyword searches are essential when the available subject heading isn’t specific enough

Try searching the MeSH database for — pharmaceutical care

What heading is retrieved? How is it defined? Does it represent the definition of pharmaceutical care that follows?

Pharmaceutical care includes “finding and responding to the drug therapy problems of patients.” Pharmaceutical care encompasses a continuum of care that begins by identifying drug therapy problems and ends with outcomes evaluation.

(The above definition is from: Becker C, Bjornson DC, Kuhle JW. Pharmacist care plans and documentation of follow-up before the Iowa Pharmaceutical Case Management Program. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2004;44:350-357.)

7. Keyword searches are essential when the available subject heading isn’t used frequently or the topic is unlikely to be indexed

For example, there are good headings for the “inpatients” and “outpatients” concepts. However, these concepts are only indexed when they are a focus of an article.

A study of the duration of amoxicillin therapy for ear infections is unlikely to be indexed as concerning outpatients.

On the other hand, a study of amphotericin use in outpatients is likely to be indexed as concerning outpatients since this drug is usually given to inpatients.

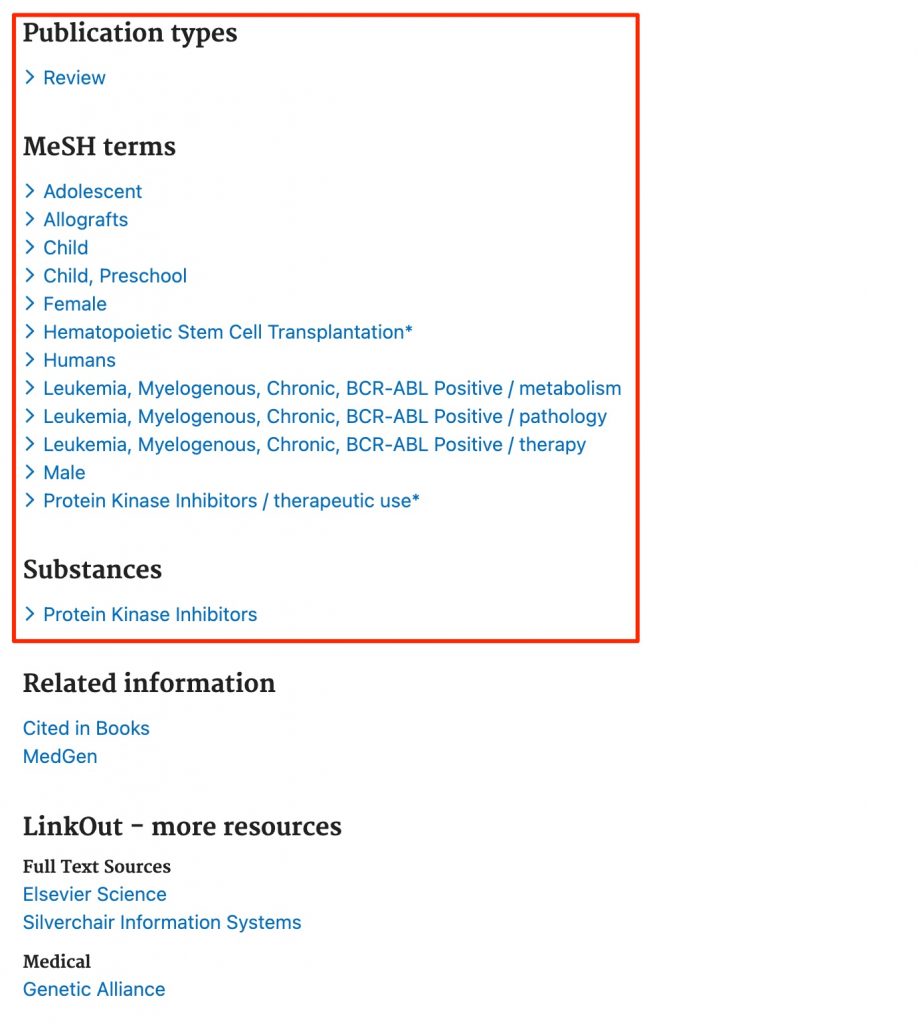

8. Keyword searches are essential when a subject heading is available but was introduced later than the earliest literature of interest to you.

Try searching the MeSH database for — social media.

You should find the following entry in the MeSH database

Can you find the introduction date in the MeSH entry for social media?

Think back over your life. Did social media become important in 2012 or earlier? (In case you don’t remember 2012, social media had been around for quite a few years before 2012.)

You can find the indexed literature published since 2012 with “Social Media”[MeSH], but would have to find earlier literature with a keyword search.

Questions, Problems, Text Errors?

Before you leave, …

- Do you have any questions or do you feel that clarification of some aspect of the materials would be helpful?

- Have you noticed any errors or problems with course materials that you’d like to report?

- Do you have any other comments?

If so, submit questions, comments, corrections, and concerns to Cindy Schmidt at cmschmidt@unmc.edu.