Objectives:

The student will:

- Be able to describe the most important differences between the datasets included in PubMed.

- Be able to explain the reasons one might wish to use subject headings to search MEDLINE.

- Be able to explain the implications of “exploding” a subject heading.

- Understand the steps in subject heading searches of PubMed

- Be able to list the types of search “concepts” that should be addressed by applying Limits.

- Understand how to create standard types of searches using recommended subject heading/subheading combinations

(7-9 are covered in the first MeSH searching tutorial only and are covered on the exam.)

- Be able to use Free Full Text buttons, PubMed GetIt!@UNMC buttons to access full-text articles.

- Be able to use the Library’s online catalog to reach full-text articles.

- Be able to use the “Similar Articles” Feature in PubMed.

_________________________________________________________________________________

Objective 1. Be able to describe the most important differences between the datasets included in PubMed.

There are two major record sets (datasets) included in PubMed:

- MEDLINE:

- is the premier database indexing the biomedical journal literature⭐

- only indexes articles published in journals meeting high quality standards. (Journals must apply for inclusion.)

- non-MEDLINE PubMed Central

- includes records for articles deposited in PubMed Central that are in journals that will never be indexed by MEDLINE .

- is composed largely of records for articles in open access journals that have applied to include all their content in PubMed Central. These journals go through a review process prior to being approved for inclusion in PubMed Central. Most of these open access journals haven’t yet made the grade for MEDLINE indexing, but they are of sufficient quality to be approved for access facilitation through PubMed Central.

- also includes records for non-MEDLINE-indexed articles that report the results of NIH-funded research ⭐ (even if this research was published in a predatory journals)

__________________

PubMed Central’s History

A few more words about PubMed Central: PubMed Central is a separate entity from PubMed. It is a ‘container’ for full-text articles. Each article in PubMed Central is represented by a PubMed record.

In the first decade of the 21st century the U.S. Congress decided that we members of the U.S. public should be able to review the results of the research that we fund, and that we should be able to see the results without charge. As a result, any articles based on research funded by NIH grants awarded in late 2007 – present must be submitted in full-text form to PubMed Central, a full-text repository ⭐ . Some of the NIH-funded articles are not made freely available until a year or two after publication (Congress decided the articles’ publishers deserved a chance to profit from their publication). PubMed Central’s reason for being is making NIH-funded research freely available. However, after PubMed Central was created, open access publishers (publishers making articles available without charge to the reader) saw the advantage of being included in PubMed Central. For this reason, PubMed created a review process for journals that wanted to make their complete contents available through PubMed central (most of these were journals not indexed by MEDLINE). Although PubMed Central and PubMed are separate entities, articles in PubMed Central are represented by PubMed records . The PubMed records for articles in non-MEDLINE-indexed journals are in the ‘non-MEDLINE PubMed Central‘ record set (which may be called PubMed non-MEDLINE).

The differences between the MEDLINE and non-MEDLINE records affect the terms that must be used in searching for these records and the filters that can be applied to a search. These differences are summarized in the table below:

| non-MEDLINE PubMed Central | MEDLINE | |

|---|---|---|

| keyword searches work⭐ | + | + |

| journal title, authors (last fm[au]) names are present in the records | + | + |

| abstracts are present in the records (if an abstract is present in the article, abstracts of very old articles may be absent) | + | + |

| Records are indexed with medical subject headings (MeSH) so MeSH searches work⭐ | + | |

| Records include language and pub date info so language and pub date limits work | + | + |

| Include species, age, and publication type info so that human vs. animal, gender, age, and publication type limits work⭐ | + |

Up to this point, you have used keywords to search PubMed. During this chapter, you will learn to use subject headings in PubMed searches. You may later choose to run combined keyword/MeSH searches, searches in which each concept is represented by a group of keywords and MeSH term/s that are all OR’d together and surrounded by a set of parentheses.

It’s important to remember that anytime a required concept is represented only by a MeSH term, your search is limited to the MEDLINE record set. None of the unindexed records are retrieved.⭐

Similarly, any time you add a filter that depends on tags or headings added by indexers (gender, age, humans vs. animals, or any publication type filters other than the systematic review filter ), your search can only retrieve MEDLINE records.⭐

_________________________________________________________________________________

Objective 2. Be able to explain the reasons one might wish to use subject headings to search MEDLINE AND Objective 3. Be able to explain the implications of “exploding” a subject heading

__________________

A. One reason for searching with MeSH is that you can often cut the number of records you will have to review.

Let’s look at whether doing a MeSH search might cut the number of records one would have to review for the “demonstration” search.

Keyword:

During this course, we’ve constructed the following keyword search for our demonstration search concerning “the efficacy of omacetaxine in CML.”

(((“BCR ABL” OR BCR-ABL* OR chronic* OR non-acute OR nonacute OR ph1 OR ph1+ OR Philadelphia*[tiab] OR “slow growing” OR slow-growing OR smolder* OR smoulder*) AND (granulocyt* OR myelo*) AND (leukaem* OR leukem*)) OR CML OR CGL) AND (Omacetaxin* OR 26833-87-4 OR Ceflatonin OR CGX-635 OR CGX635 OR HHT OR Homoharringtonine OR NSC-141633 OR NSC141633 OR Chuan-Shan-Ning OR Fu-Er OR Gao-Rui-Te OR Hua-Pu-Le OR Jin-Nuo-Xing OR Sai-Lan OR Wo-Ting OR Synribo) Filters: English

As of 5/29/2025, The number of records retrieved by the keyword search was

193 total records retrieved

174 of the 193 are indexed in MEDLINE

4 of these pre-date December 1989. These cannot be retrieved by a MeSH search.

(CHALLENGE — WATCH FOR THE REASON articles pre-12/1989 can’t be retrieved by the MeSH search. Can you spot it before it’s explained?)

19 of the 193 are unindexed records (mostly non-MEDLINE PubMed Central records). These can’t be retrieved by a MeSH search.

MeSH:

During this lesson, you’ll follow along with construction of the MeSH search for the demonstration topic. We’ll end up with the following strategy:

(“Homoharringtonine”[Mesh]) AND ( “Leukemia, Myelogenous, Chronic, BCR-ABL Positive/therapy”[Mesh] ) Filters: English

The number of records retrieved by the MeSH search on 05/29/2025= 81

(Since the search requires the presence of subject headings in the records retrieved, only records indexed in MEDLINE are retrieved.)

Number of records one has to review:

If you’ve decided to review all the literature on our demonstration topic and only run a keyword search, you would have to review 200 records.

If you’ve decided to review all the literature on our demonstration topic and you run both a keyword search and a Mesh search, you have to review 18 unindexed records retrieved by the keyword search + 4 pre-1989 records retrieved by the keyword search +85 records indexed by MEDLINE = 107 records total

Adding the MeSH search cut out almost half of the work involved in reviewing records and the MeSH search itself took very little time to construct.

__________________

B. One medical subject heading (mesh) can usually be used for each search concept.⭐

One of the advantages of a MeSH search is that it is usually easier to construct than a keyword search. This is true, in part, because there is usually a single heading for each search concept.

Notice in the search below, that the omacetaxine and CML concepts are each represented with a single medical subject heading (a single MeSH).

(“Homoharringtonine“[Mesh]) AND ( “Leukemia, Myelogenous, Chronic, BCR-ABL Positive/therapy”[Mesh] ) Filters: English

The only subject heading available to the indexer for typical BCR-ABL positive CML is “Leukemia, Myelogenous, Chronic, BCR-ABL Positive.” Regardless of which synonym for typical CML has been used by an author, the indexer will use the “Leukemia, Myelogenous, Chronic, BCR-ABL Positive” MeSH.

Since you don’t have to find all the synonyms for a concept when you construct a MeSH search, MeSH searches are often easier to construct than keyword searches. When you need to find an article or a few articles quickly and that article doesn’t have to be the most recent publication on a topic, a MeSH search may be an easy way to get what you need.

__________________

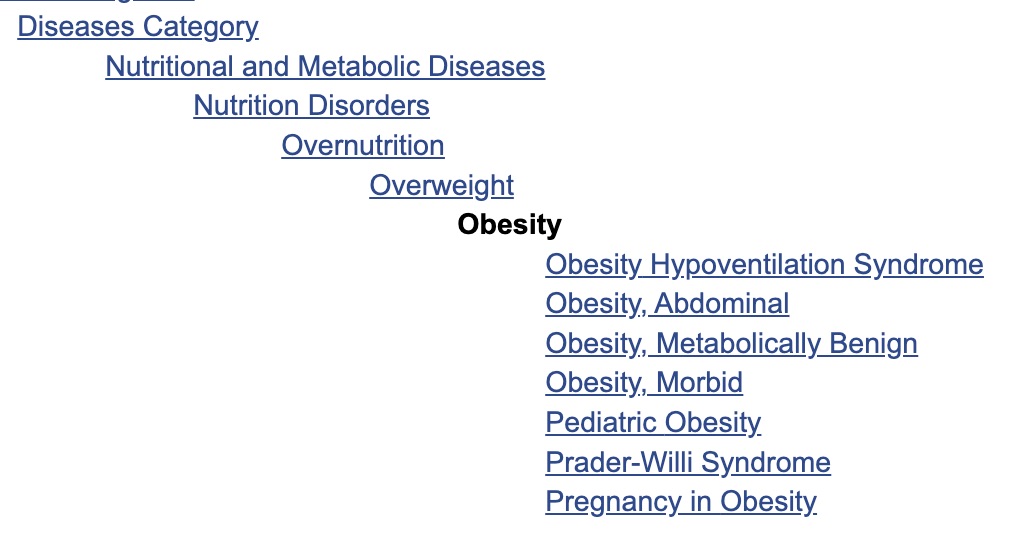

C. MeSH terms are organized in trees. Searching the broadest term will also retrieve records indexed with the narrower terms (exploding the heading).⭐

MeSH searches are most useful when you want to search for articles about a whole category of diseases/drugs/behaviours/etc. This is because MeSH headings are organized in ‘trees’ and searches that contain a broad heading will retrieve records containing that broad heading and any narrower headings. A search containing a broad heading with a subheading, will retrieve records containing that broad heading/subheading combination and any records containing the narrower headings with that same subheading.

-

- Please, open a new internet browser window and use that window to go to UNMC’s version of PubMed.

- Click on the “MeSH Database” link in the “Explore” list on the right-hand side of the PubMed homepage.

-

- Search the “MeSH database” for —

cancer

-

- click on the “Neoplasms” heading. (Neoplasms is the broad MeSH term used to index both cancerous and benign growths).

- Scroll to the bottom of the page. You will see the Neoplasms heading above a long list of narrower headings. These headings are shown below in several columns so that the list takes less space. A search strategy containing the “Neoplasms” heading without subheadings, will retrieve the records for all the articles indexed with the “Neoplasms” heading or one of these narrower headings or one of the headings displayed if you click on one of the narrower headings’ plus marks (with or without a subheading).

Remember because of “explosion“:

-

-

- Broad headings retrieve the broad heading and narrower headings

- Narrow headings do NOT retrieve broader headings.

- Headings without subheadings retrieve headings with or without subheadings.

- Headings with subheadings retrieve that heading with that subheading and narrower headings with that subheading (and any narrower subheadings).

-

______

Check your understanding of MeSH explosion (Objective 3)⭐:

Use the “Obesity MeSH tree” screenshot below to answer the questions that follow:

__________________

D. Subject headings only retrieve items that have been indexed as focusing some attention on a topic⭐

Indexers only add a heading to an article’s record if the article focuses some considerable attention to the heading topic. So MeSH-based searches (heading-based searches) retrieve records that give some attention to the heading topics.

Keyword searches retrieve records for articles which have titles or abstracts that contain the keyword. Let’s say you’re searching for articles about use of methotrexate in cancer patients. Your keyword search would include the “methotrexate” concept and the “cancer” concept (which would include neoplastic, neoplasm*, malignan* , and many other cancer synonyms). It would retrieve many relevant articles about the use of methotrexate in cancer and a few irrelevant articles with abstracts containing sentences like:

-

- We will review the use of methotrexate for non-neoplastic conditions

- In this article, part I of the series, we review use of methotrexate in inflammatory conditions. Next month’s article (part II) will be devoted to methotrexate’s use in cancer.

- This study examined the effectiveness of methotrexate in advanced rheumatoid arthritis. Patients visiting the rheumatology clinic between September 2019 and September 2020 were eligible to participate. Those with a history of cancer, non-rheumatoid kidney disease, and diabetes were excluded from the study.

MeSH heading -based searches, thus, retrieve fewer irrelevant results than keyword searches.

__________________

E. The searcher can force relationships between search concepts by using subheadings with headings⭐.

The searcher can often use heading/subheading combinations to force relationships between heading concepts. For example, if you want to know about —

the efficacy of specific drug treatment in a specific disease.

You can require that:

1) the retrieved records contain the drug heading with the “therapeutic use” subheading (“Drug/therapeutic use”[MeSH])

and also

2) the disease heading with the “therapy” subheading (“Disease/therapy”[MeSH]).

(“Drug/therapeutic use”[MeSH]) AND (“Disease/therapy”[MeSH])

__________________

F. As the most common journal article topics are indexed in a predictable manner, standard, search templates can be used to guide searches on these topics⭐.

The three templates listed below are especially important for drug information searches

1. Drug A causes Disease B

(“Drug A/adverse effects”[mesh] ) AND (“Disease B/etiology”[mesh])

The word “etiology” means cause.

2. Drug A used to treat Disease B

( “Drug A/therapeutic use”[mesh]) AND (“Disease B/therapy”[mesh] )

3. Drug A used to prevent Disease B

“Drug A”[mesh] AND “Disease B/prevention and control”[mesh]

Additional concepts can, of course, be added to the types of searches above. The templates are just intended to guide the construction of a portion of your search.

Notes:

In the templates above “Drug A” heading can be replaced with a “Drug Class A” heading or a “Procedure A” heading.

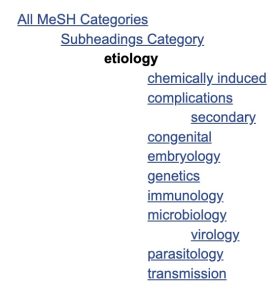

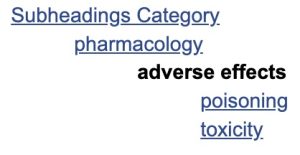

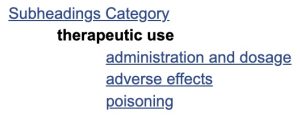

The templates above are optimized for PubMed. PubMed explodes subheadings. Broad subheadings retrieve narrower subheadings in the same subheading tree. The “etiology” subheading is in the same tree and broader than the “chemically-induced” subheading (figure “a” below). The “adverse effects” subheading is in the same tree and broader than the “poisoning” and “toxicity” subheadings (figure b). The “therapeutic use” subheading is in the same tree and broader than the “administration and dosage” subheading (figure c). The “therapy” subheading is in the same tree and broader than the “drug therapy” subheading (figure d).

(a) (b)

(b)  (c)

(c) (d)

(d)

______

Check your understanding of the search templates by answering the following questions. You may want to keep a record of these questions and their correct answers. This information will help you plan your work on this week’s assignments.

_________________________________________________________________________________

Objective 4. Understand the steps in subject heading searches of PubMed

The steps in a MeSH search are shown in the box below. We’ll go through these steps one at a time.

Steps in a MeSH Search⭐

-

- Outline/list the concepts contained in your question

- Identify the concepts that are limits/filters (Objective 5)

- From the non-limit concepts identify the concepts that are likely to be headings and those that are likely to be subheadings.

- Does the search (or part of the search) fit a search template? ________________________

- Go to the MeSH database, find and select the first heading or heading/subheading combination and add it to the “Search Builder” box. Detailed instructions:

-

-

- Go to the MeSH database

- Search for the heading for your concept.

- If more than one search result appears, click on the actual MeSH heading for your first concept to open the detailed record for the heading.

- Make a record of the year the heading was introduced

- Select any needed subheading/s (only use subheadings if they are of central importance to your search)

- Use the “Add to Search Builder” button to add your heading or heading/subheading combination to the PubMed search box .

-

-

- At this point you can either:

-

-

- Click the “Search PubMed” button to search one MeSH heading at a time and then join concepts using the “Add to Query” feature in the “History and Search Details” table on the “Advanced” search page.

-

or

-

-

- Continue searching the MeSH database (one concept at a time). Add each heading or heading/subheading combo to the the PubMed search box, until all concepts with MeSH headings are present. in the search box. Correct the strategy in the “PubMed Search Builder” if necessary. Pay special attention to parentheses and Boolean operators. Click the “Search PubMed” button.

-

-

- Perform keyword searches for those concepts not represented by MeSH terms.

- If needed, use the “Add to Query” feature in the “History and Search Details” table on the “Advanced” search page to join the strategies for separate search concepts into a single search strategy.

- Apply Limits/filters (in left-hand margin) If needed, use the “Additional Filters” button to select and “Show” any needed filters that are not already available in the left-hand margin.

- Does the number of results seem reasonable? If not, consider changing article type filters and/or removing subheadings. You may want to try the search again after removing subheadings.

__________________

-

Outline/list the concepts contained in your question in a Word document.

Demonstration Search Topic: What are the important concepts in our “demonstration” search. question: What is the evidence concerning efficacy of omacetaxine in CML?

__________________

-

Identify the concepts that are limits/filters (Objective V)

Limit concepts are either:

a) publication characteristics –– publication type, publication date, publication language (only date and language limits can be used in PREMEDLINE searches)

or

b) ‘experimental subject’ characterstics — human vs. animal, female vs. male, age groups

Demonstration search concepts:

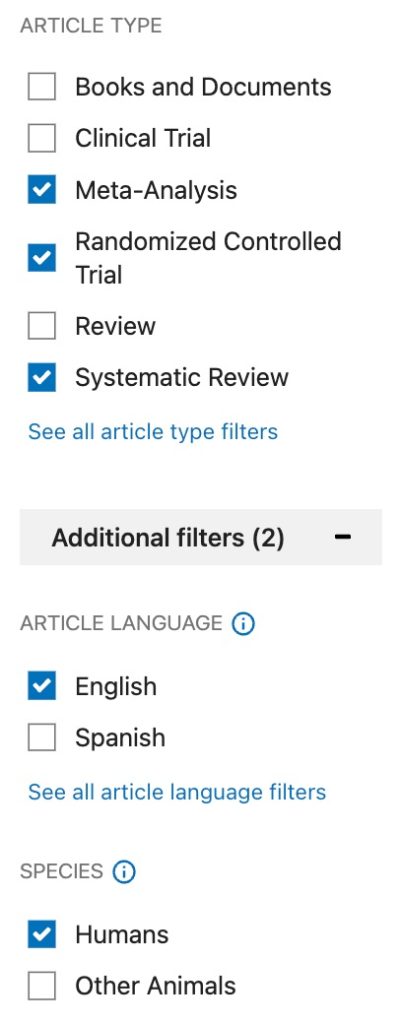

Limit concepts: English, Humans, Systematic Reviews, Meta-analyses, or Randomized Controlled Trials.

Remaining concepts

use of omacetaxine

treatment of CML

__________________

-

From the non-limit/non-filter concepts identify the concepts that are likely to be headings and those that are likely to be subheadings.

______

a. “Stand alone” concepts likely to be subject headings include:

-

- names of diseases or categories of diseases,

- names of drugs/therapies or categories of drugs/therapies

- names of organs or body parts

- wounds and injuries of body parts

- names of organisms or animals

- names of infections

- Please note: There are different headings for infectious agents and the diseases they cause (e.g. “Helicobacter pylori”[mesh] vs. “Helicobacter infections”[mesh])

-

- names of procedures or tests or the names of categories of procedures or tests,

- names of specialties or professions,

- types of study design,

- types of programs

______

b. subheadings are aspects of subject heading concepts — can usually be linked to a heading concept with a preposition (e.g. therapy for____, treatment of ______)

Demonstration search concepts:

Limit concepts: English, Humans, Systematic Reviews, Meta-analyses, or Randomized Controlled Trials.

Heading concepts (bold-face and underlined)/subheading concepts (italics)

omacetaxine/therapeutic use

CML/treatment

__________________

-

Does the search (or part of the search) fit one of the search templates listed below? If so does the template change your plan?⭐

Does the search (or part of the search) fit one of the search templates listed below? If so does the template change your plan?

a. Drug A causes Disease B

(“Drug A/adverse effects”[mesh] ) AND (“Disease B/etiology”[mesh])

b. Drug A used to treat Disease B

( “Drug A/therapeutic use”[mesh]) AND (“Disease B/therapy”[mesh] )

c. Drug A used to prevent Disease B

“Drug A”[mesh] AND “Disease B/prevention and control”[mesh]

__________________

-

Go to the MeSH database. Search for and select the actual MeSH heading for your first concept, apply any needed subheadings (only use subheadings that are of central importance to your search), use the “Add to Search Builder” button to add it to the PubMed search box .

| Video showing construction of the MeSH search for articles about use of omacetaxine to treat CML |  |

I encourage you to follow along and complete the steps in the search while you watch the video. If you complete this search and the two lab searches, you will have gone through this process at least three times. The more times you go through the process of building a MeSH search, the more sense the process makes and the easier it is to remember. The steps shown in the video are also described in the narrative below:

______

a. Search for your first concept.

-

- Access PubMed by either going to:

- the Library’s homepage –>”Resources”–>”Literature Databases” link –> “PubMed” link

- Access PubMed by either going to:

or

-

-

- in Canvas, use the “Library” link –> “MEDLINE via PubMed” link.

- Click the “MeSH Database” link in the “Explore” column on the right-hand side of the PubMed homepage.

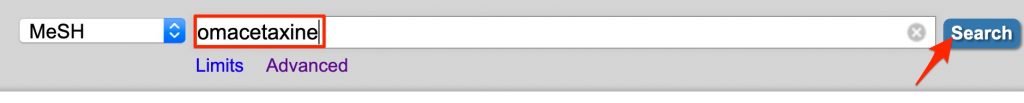

- Search for the Medical Subject Heading for one of your search concepts. Let’s start with — omacetaxine

-

______

b. Select the actual MeSH heading needed

-

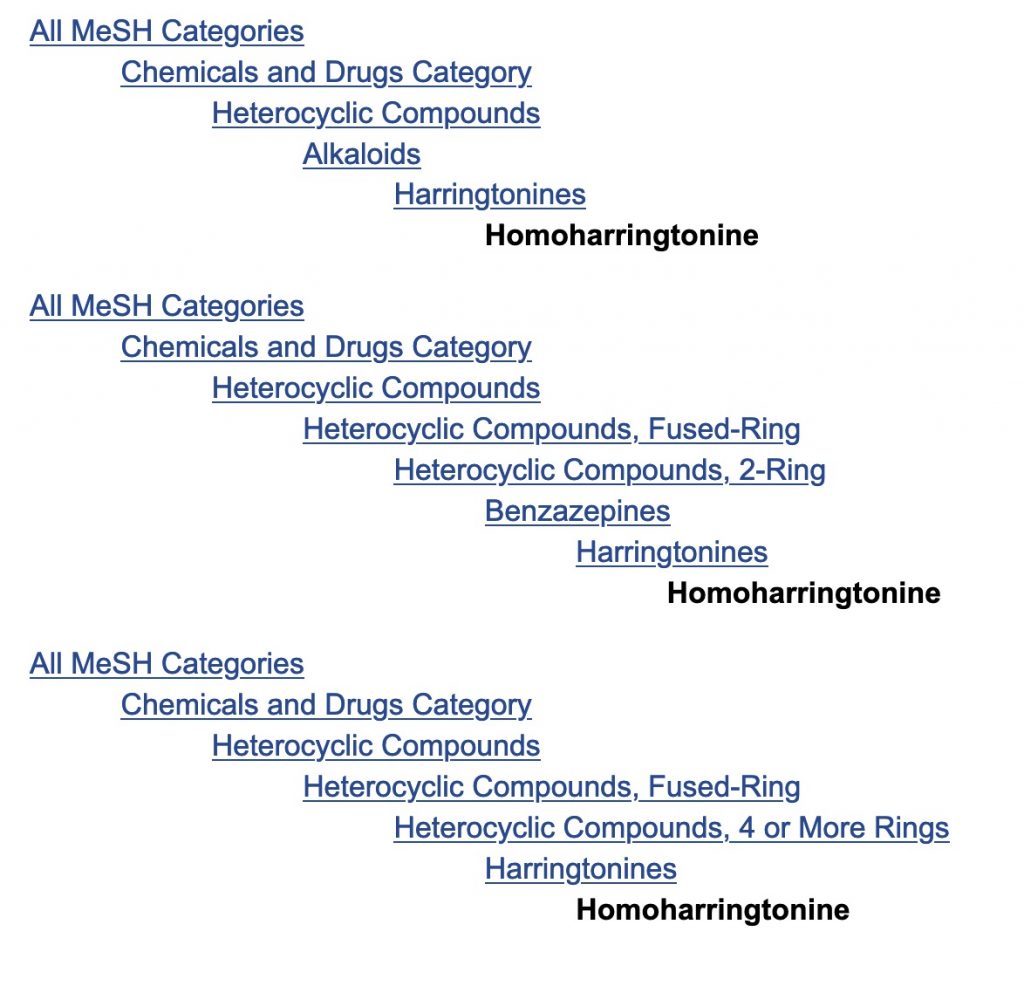

- In this case a heading for “Homoharringtonine” is retrieved. You may remember that homoharringtonine is a synonym for omacetaxine so this is a great heading for our search.

Sometimes a list headings will be retrieved and you will have to scan the list looking for a relevant heading and then click on the best heading. At other times, none of the headings retrieved will meet your needs, and you will need to try the searching the MeSH database again, this time with another synonym for your concept.

-

- Before settling on a heading, it’s best to scroll to the bottom of the page and look at the MeSH trees.

- In this case, the “Homoharringtonine” heading retrieved initially is best.

- Sometimes a broader or narrower heading is better than the heading originally retrieved.

______

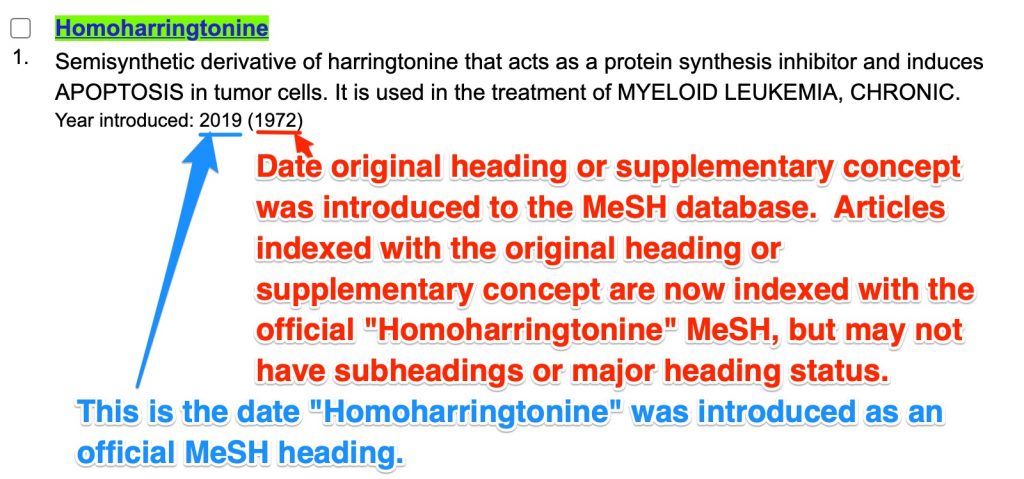

c. Make a note of the “Year Introduced” data

-

- Before selecting the planned subheading, make a note of the “Year Introduced” data.

A heading can’t retrieve PubMed records indexed before the heading’s introduction to the MeSH database. We will use the “Homoharringtonine” heading’s “Year Introduced” data along with other heading introduction dates to determine what part of PubMed our MeSH search can probe.

-

- What if a heading has two introduced dates like the “Homoharringtonine” heading? This means the current heading is either worded differently than the original heading or the heading was once a “supplementary concept” (an unofficial MeSH that doesn’t have subheadings or “major” status possibilities).

- The earlier (longer past) introduction date determines what the heading without subheadings can retrieve.

- If the heading you’re working on is a non-drug heading, a heading/subheading combination will probably retrieve PubMed records dating back to the earlier introduction date.

- If the heading you’re working on is a drug heading, it’s likely that the heading was once a “supplementary concept” (an unofficial heading with no available subheadings.) A drug heading/subheading combination (because of the inclusion of the subheading) will probably only retrieve PubMed records dating back to the later (more recent) introduction date — when the heading became an official MeSH.

- What if a heading has two introduced dates like the “Homoharringtonine” heading? This means the current heading is either worded differently than the original heading or the heading was once a “supplementary concept” (an unofficial MeSH that doesn’t have subheadings or “major” status possibilities).

______

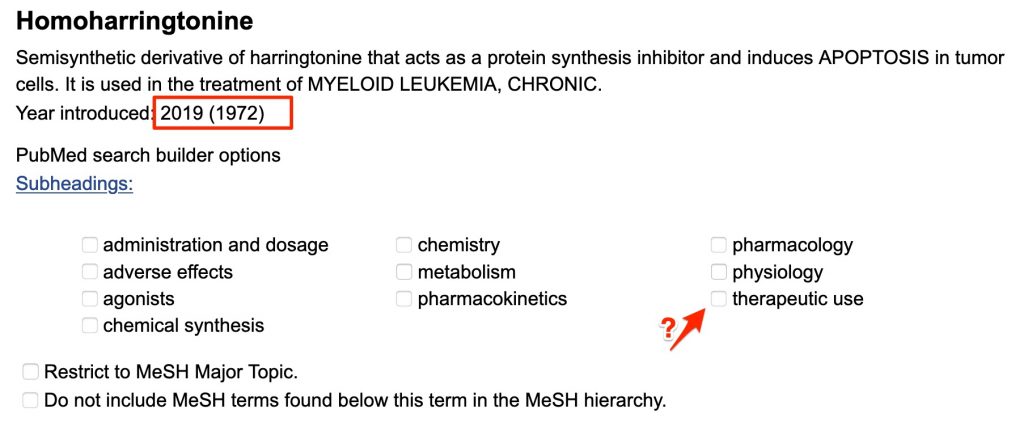

d. Select a subheading if desired

We had planned to use a “therapeutic use” subheading with the omacetaxine heading. However, that would probably limit our search to retrieval of very recent literature (post-2019 literature). It’s probably best to leave out the subheading.

For the exam:

Remember a search using a heading without a subheading, will retrieve any literature indexed with that heading with or without subheadings and any literature indexed with narrower headings with or without subheadings.⭐

-

- To use a heading without subheadings, just leave the subheadings unchecked

______

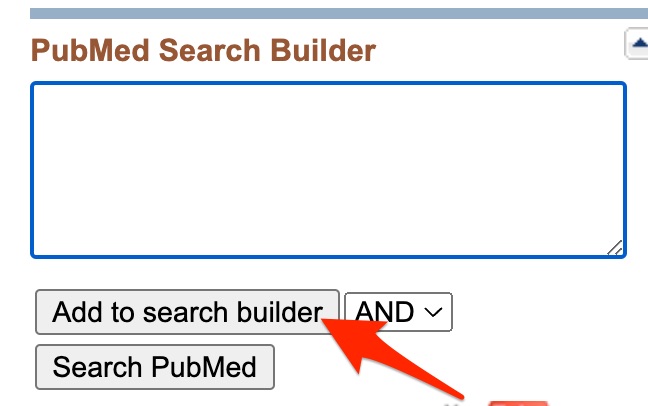

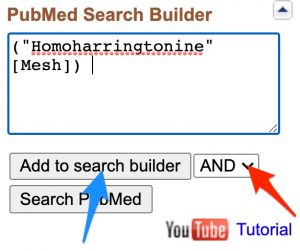

e. Click the “Add to Search Builder” button

-

- Click the “Add to Search Builder” button.

The formatted MeSH heading (surrounded in quotes with a [MeSH] tag) will appear in the “PubMed Search Builder.”

![A screenshot shows the "Homoharringtonine"[MeSH] formatted heading in the "PubMed Search Builder" box.](https://pressbooks.nebraska.edu/app/uploads/sites/77/2020/06/homoharringtonine-builder.jpg)

__________________

-

At this point you can either take one of two approaches:

Approach 1: Click the “Search PubMed” button to search one MeSH heading at a time. Later, join concepts using the “Add to Query” feature in the “History and Search Details” table on the “Advanced” search page.

Approach 2: Continue searching the MeSH database (one concept at a time). Add each heading or heading/subheading combo to the the PubMed search box. Continue until all concepts with MeSH headings are present in the search box. Correct the strategy in the “PubMed Search Builder” if necessary. Pay special attention to parentheses and Boolean operators. Click the “Search PubMed” button.

We’ll take the second approach here.

______

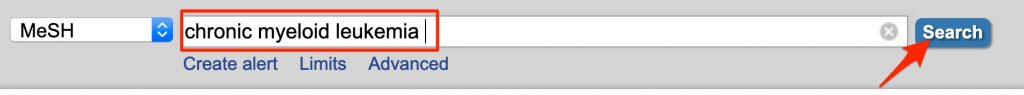

a. Search for your next concept.

-

- Go back to the MeSH search box at the top of the page, remove the current contents and enter the second concept — chronic myeloid leukemia

______

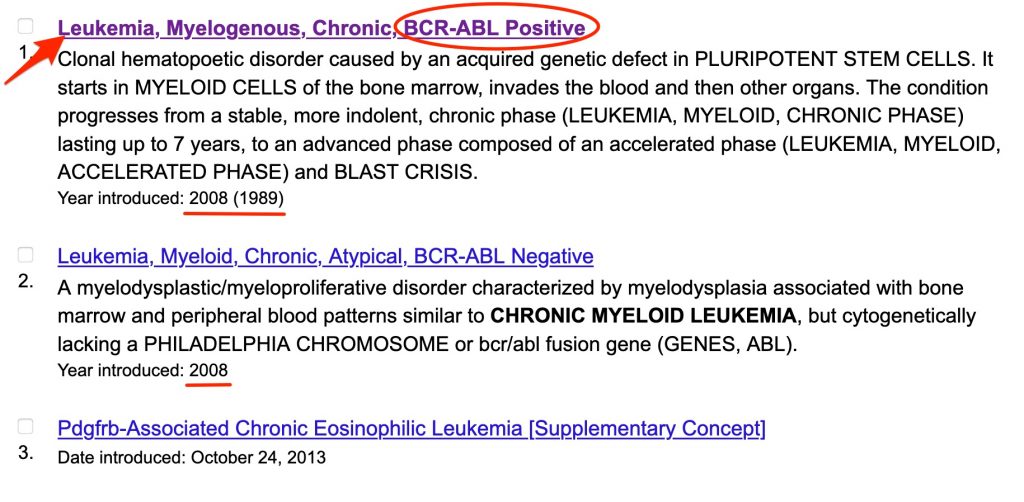

b. Select the appropriate heading

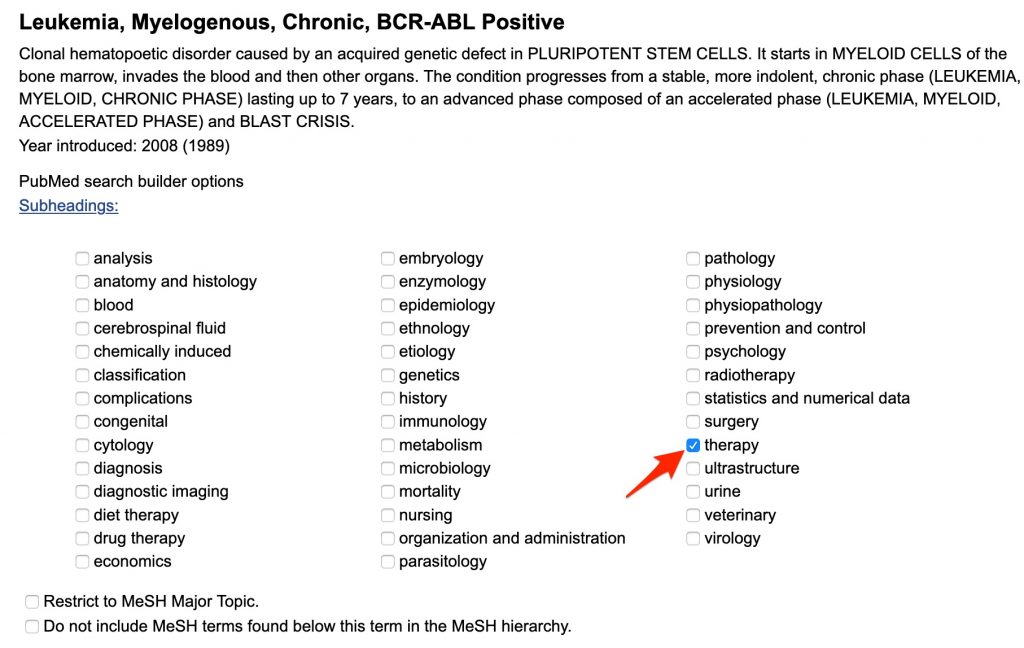

In this case, a list of headings is retrieved and we have to decide which to use. We are interested in typical, BCR-ABL positive CML.

-

- Click on the “BCR-ABL Positive” heading.

-

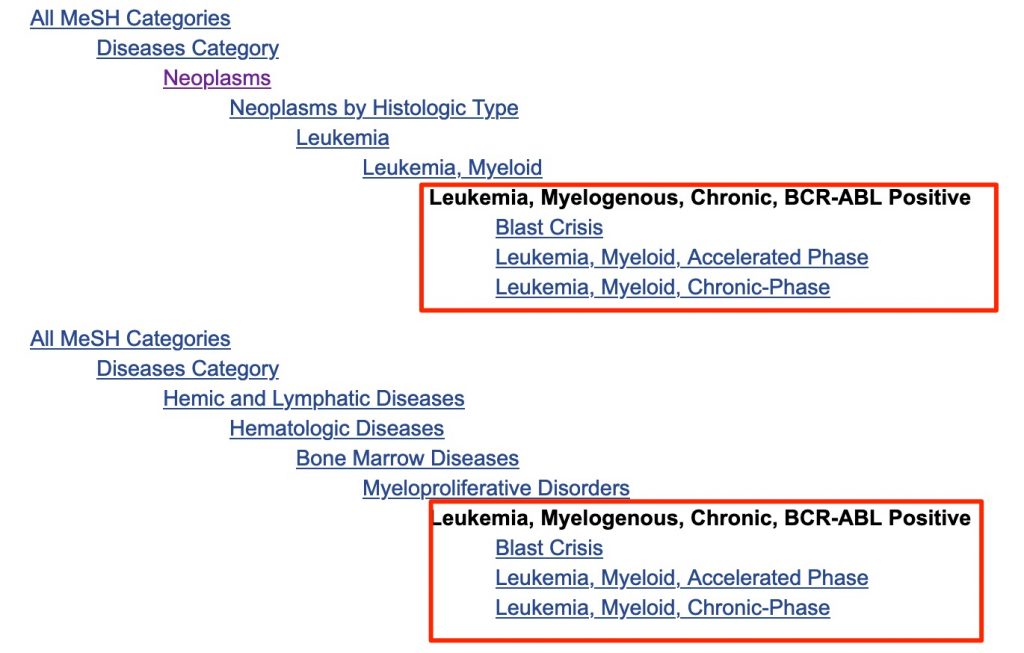

- Scroll to the bottom of the page to check the MeSH trees. Do we want a broader or narrower heading?

- Scroll to the bottom of the page to check the MeSH trees. Do we want a broader or narrower heading?

Our search question specified interest in CML in general (all phases). So the current heading is best. It will retrieve PubMed records with the heading for BCR-ABL+ CML as well as records containing the headings for the three phases of BCR-ABL+ CML

______

c. Make a note of the “Year Introduced”

-

- Scroll to the top of the page. Find and note the “Year introduced”

______

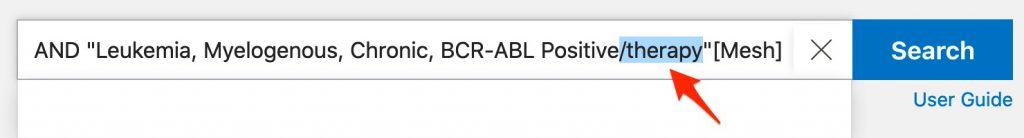

d. Consider selecting a subheading

-

- We had planned to use a “therapy” subheading. Check the “therapy heading”.

- Since this isn’t a drug heading we don’t need to worry about the more recent date — it probably just represents a change from one heading (with subheadings) to a heading that is worded differently. The old heading will have been changed to the new heading in PubMed records.

______

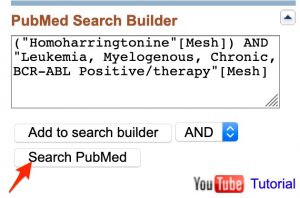

e. Select the appropriate Boolean operator and click the “Add to search builder” button

Do we want to join the “CML” heading to the “homoharringtonine” heading (the heading for omacetaxine) with AND, OR, or NOT?

-

- Choose the appropriate Boolean operator (AND is used to join disparate concepts).

- Click the “Add to search builder” button.

______

f. If we had other concepts we would repeat these steps again.

______

g. Click the “Search PubMed” button.

__________________

-

If no appropriate heading was found for a concept, a keyword search for that concept would be added to the search strategy.

__________________

-

If needed PubMed’s “Advanced” search page can be used to join query’s in the “History and Search Details” table.

__________________

-

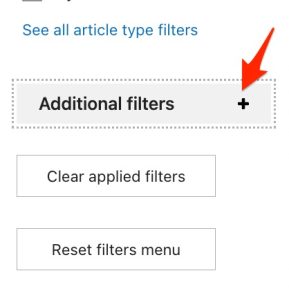

Apply Limits/filters if needed

We have planned to apply the following filters:

English

Humans

Systematic reviews, meta-analyses, randomized controlled trials

- If these filters are not immediately available on the left-hand side of the page:

- click on the “Additional filters” button.

- One at a time, select the desired filters. The page will refresh after each filter is added.

When multiple article type filters are added using the options available on the left-hand side of the page, these filters are OR’d together.

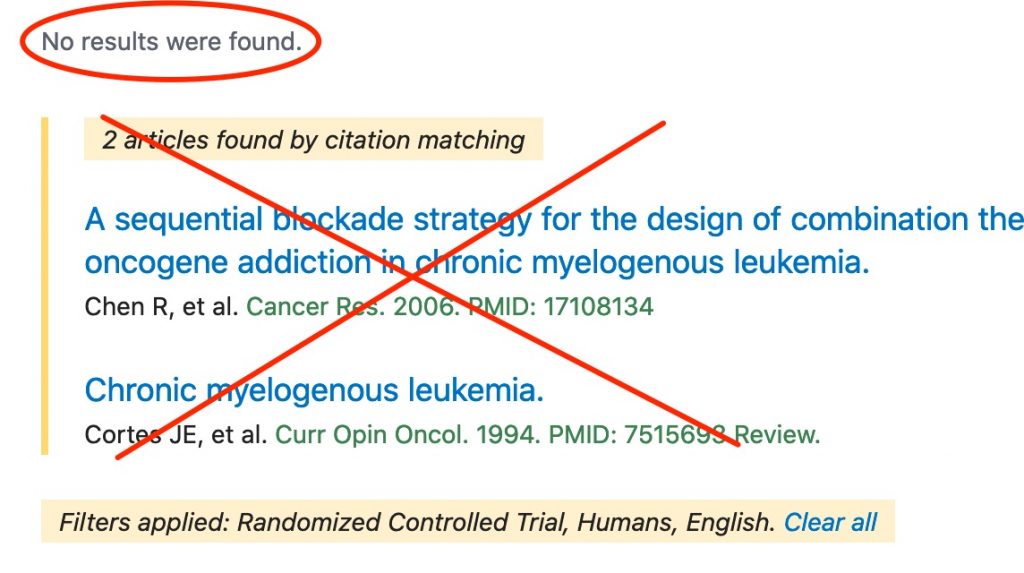

- If no results are retrieved, a “No results were found” message will appear. However, “citation matching” results may still be found. For the purpose of this class, ignore any “citation matching” results.

__________________

10. Does the number of results seem reasonable and /or meet your needs? If not, consider changing article type filters and/or removing subheadings.

The fact that no articles of the types of greatest interest (randomized controlled trials, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses) were found doesn’t mean that there is no evidence relevant to our search question. There may be lower level evidence or articles that haven’t been indexed with the subheadings you used.

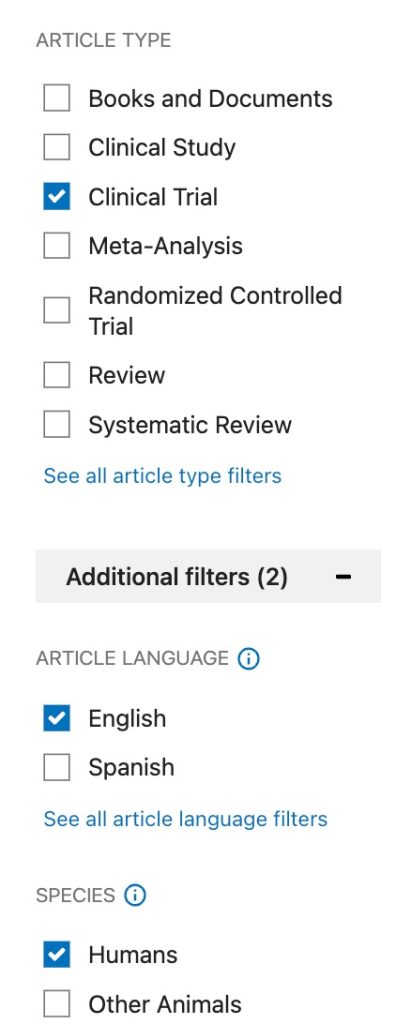

- Try changing the article type filters first.

- Un-check all the publication type filters you’ve applied. You shouldn’t have to do this, but PubMed sometimes gets ‘stuck’ and keeps giving zero results even if additional publication types (with results) are added. Removing the previous publication type filters seems to shake the search engine out of this rut.

- Apply the “Clinical Trial” publication type. This publication filter finds both randomized and non-randomized trials.

When this Pressbook was last updated, the search with a “clinical trial” filter retrieved 15 results. Most looked relevant.

- Try removing the subheading– /therapy. (It’s always worth trying a search without subheadings to see what happens.)

In this case (with the filters we have chosen), the number of results doesn’t change when the subheading is removed.

_________________________________________________________________________________

Assignment

- Complete the “Using MeSH to Search PubMed, Part I” tutorial.

- The tutorial will guide you through a search for articles about kidney diseases caused by sirolimus.

- After completing the search, you will be asked to go to the “Advanced” search page, scroll down to the “History and Search Details” page, copy the row/rows containing your search strategy, and paste it into a search document. Save the document.

- Submit the document through Canvas. Please, check to be sure the entire search is visible in the submitted document.

- Complete the “Using MeSH to Search PubMed, Part II” tutorial.

-

- The tutorial will guide you as you complete the MeSH search for your final search assignment.

- After completing the search, you will be asked to go to the “Advanced” search page, scroll down to the “History and Search Details” page, copy the row/rows containing your search strategy, and paste it into a search document. Save the document.

- Please, keep a copy of the saved Word document in your own files until after the mid-term exam. Students sometimes submit a document that is somehow converted to a pdf that shows only a part of the search history or that needs revision. If the student doesn’t have the original Word document, they may have to start over creating search strategies.

- You will also be asked to include introduction dates for the headings in your Word document.

- Submit the document through Canvas as your FSA3 assignment. Please, check to be sure the entire search appears in the submitted document.

_________________________________________________________________________________

Questions, Problems, Text Errors?

Before you leave, …

- Do you have any questions or do you feel that clarification of some aspect of the materials would be helpful?

- Have you noticed any errors or problems with course materials that you’d like to report?

- Do you have any other comments?

If so, you can submit questions, comments, corrections, and concerns a to Cindy Schmidt at cmschmidt@unmc.edu.