33 The Risk for Malnutrition Increases With High Age

Sabine Zempleni and Sydney Christensen

Retirement is a life event that can drastically change the daily life of an older individual. For some this may give them an opportunity to have more time with those that they love and to follow their passions. However, for others the end of work life greatly reduces cognitive stimulation and social contact, especially if the workplace was their main source of socialization and income. As the years go by, many older individuals will also lose loved ones, which further increases the risk of isolation.

Regular social contact, engaging in a variety of activities and solving complex problems are essential to reduce the risk of cognitive decline and depression. Depression and cognitive decline can lead an older individual to neglect their basic needs such as regular, nutrient-rich meals and daily physical activity and exercise. Maintaining multiple active roles as parent, spouse, employee or volunteer can increase feelings of being valued and encourage a healthy outlook on life.

Declining physical capabilities can also impact wellbeing and health. At the beginning of this unit you learned that growing older involves a decrease in body functioning no matter how healthy of a lifestyle a person has lived. Loss of bone mass, some degree of atherosclerosis, shifts in hormone function result in a more achy body and slowly declining health.

On a cellular level declining mitochondrial function results in increased fatigue. The accumulation of cellular garbage increases low-grade chronic inflammation. The reduced ability of cells to fold proteins properly results in lower muscle synthesis. The result is that people in high age are less active and have to take more breaks.

Malnutrition, common in high age, accelerates the loss of muscle mass and cognitive decline. Many older individuals experience loss of appetite and begin to consume fewer calories and nutrients resulting in malnutrition. Frailty develops. Combined with other related health issues the risk of falls, disease and hospitalizations increases. Any of these issues can ultimately lead to an early death.

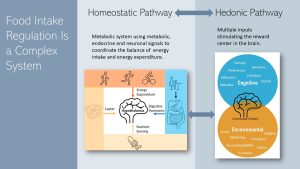

Before you study the age-related loss of appetite, here is a quick review how energy intake is regulated. This will allow you to gain a deeper understanding of malnutrition in high age:

There are the two major physiological pathways regulating food intake.

One is the homeostatic pathway that regulates the balance between energy intake and expenditure. This pathway increases the motivation to eat when energy stores are depleted and triggers satiety after a meal. The homeostatic pathway can also increase or decrease the efficiency of the energy metabolism.

The command center of the homeostatic pathway is the brain and there are four major inputs.

- The first input is the secretion of digestive hormones. After food is digested and the stomach is empty the stomach starts to secret ghrelin into the blood circulation. Once we eat and the stomach fills up pressure receptors read the degree of expansion. Ghrelin secretion subsides. The hypothalamus reads the amount of ghrelin circulating the blood stream. High ghrelin stimulates feelings of hunger while declining ghrelin increases the feeling of satiation. While food is digested and moves along the digestive tract, other digestive hormones such as CCK, GLP-1 and PYY are secreted by the small intestine. Primarily, these hormones coordinate digestion but also prepare the metabolism for the incoming nutrients. The hormones enter the blood circulation and message the status of the digestion to the brain to suppress appetite depending on macronutrient composition and food amount. This is the reason why we usually do not have a drive to eat right after a meal.

- The second input is nutrient sensing. As absorbed nutrients circulate in the blood stream certain nutrients and their metabolites are tracked by the brain. This information is combined with the other inputs of the homeostatic pathway to increase or decrease appetite.

- The third input is the signaling from existing energy stores. Leptin is one of the hormones involved here. Again, the hypothalamus in the brain monitors leptin blood concentrations. A decrease of leptin secretion with shrinking adipose tissue increases the drive to eat. Increasing leptin secretion with growing adipose tissue tends to reduce appetite.

- The fourth input from the homeostatic system is the energy expenditure. Even when we are at rest our metabolism will require energy. For example, increasing energy expenditure by exercising vigorously is read and appetite increased accordingly.

Interestingly, the drive to eat during an energy shortage is much more potent than the downregulation of the appetite when energy becomes abundant again. Therefore, gaining weight is much easier than losing weight.

Eating does not just provide energy and nutrients but is also a pleasurable experience. This is where the second pathway, the reward-based regulation or hedonic pathway, comes in. The inputs for the hedonic pathway vary and are complex. These cues mostly stimulate the pleasure center of our brain.

In past centuries food supply varied from shortage to abundance. Filling up energy stored would allowed to weather food shortages. Therefore, during times of abundant food supply the hedonic pathway will override the homeostatic pathway by increasing the desire to eat palatable foods. Today’s food environment fuels this physiological overeating by providing ubiquitous and abundant amounts of very tasty food.

Cues stimulating the hedonic pathway can be cognitive. Sensory cues such as seeing, smelling and tasting delicious food increase food consumption. Habitual eating behavior and our social environment also alter food consumption. Some individuals have excessively restricted eating behaviors while others eat uninhibited. Emotions ranging from being bored to happy to sad to stressed can influence how much we eat. How much those psychosocial factors impact eating decisions varies widely between individuals.

You Will Learn:

- Malnutrition is common in high age due to a lack of access to healthy meals, reduced quality of meals, and reduced mealtime experience

- Anorexia of aging fuels malnutrition, sarcopenia and frailty.

- Physiological changes make seniors vulnerable to malnutrition.

- When eating difficulties develop, meals become stressful and appetite decreases.

- Gastrointestinal changes increase satiety.

- Chronic diseases impact appetite.

- Nutritional status in people over age 65 can be measured with the mini nutritional assessment.

- What can seniors do to prevent eating difficulties and reduce the risk for chronic diseases?

- A diet for seniors should be nutrient dense and provide adequate amounts of protein.

- Adequate hydration improves health and cognition

- Water, protein, vitamin B12, vitamin D, and omega-3 fatty intake need special attention.

- Can a healthy lifestyle prevent or slow down cognitive decline?

Malnutrition Is Common in High Age

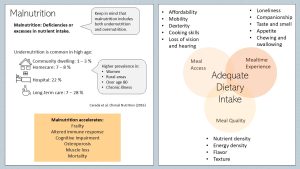

The WHO defines malnutrition as either deficiencies or excesses of nutrients. This means that malnutrition can be under- or overnutrition. The desired nutrition status is an adequate nutrient intake that will allow for optimal physical functioning and the maintenance of some nutrient stores. During this chapter malnutrition will refer to undernutrition.

As people enter high age the risk for undernutrition increases. Undernutrition is least common in community dwelling older people (1 – 3 %). This is not surprising since this group lives independently in their own apartments or houses. They tend to be fit enough to take care of themselves, choose the food they prefer and are engaged in their community.

Once an older person requires homecare the prevalence rises to 7 – 8 %. People in hospital settings and long-term care facilities are even more likely to have malnutrition, up to 28 %.

Adequate nutrition is one of the main factors determining how long and more importantly how well a person lives. Malnutrition can trigger weight loss which always affects lean mass. A loss of muscle mass and strength can speed up frailty along with cognitive impairment. These are all risk factor for a premature death.

Specific nutrient deficiencies can impact quality of life. Calcium and vitamin D deficiency accelerate osteoporosis increasing the risk for painful fractures. Low protein intake and vitamin D deficiency will lead to a loss of muscle mass. Daily living will become difficult. Low vitamin intake will alter the immune response leading to a vulnerability for infectious diseases. Low intake of antioxidant nutrients will fuel inflammatory processes.

This makes it clear that the key to a long quality life is an adequate dietary intake.

Standard nutrition recommendation tend to focus on recommending adequate nutrient amounts. This sounds easy, but nutrients come from food and adequate food intake depends on multiple factors. When giving dietary advice all meal related factors need to be considered.

Access to meals: Poverty increases with age. People over 80 years old have a higher poverty rate than any other age group in the US. The poverty rate in elderly increases from roughly 8 % in 65 to 69 year old adults to 11 % in the 80+ year old group. The group of seniors most affected are Black and Hispanic Americans and never-married, single women over 65 years old (18 %, 17 %, 17 % respectively). As you have learned in the food insecurity chapter, poverty is a major predictor for the inability to purchase sufficient quality and quantity of foods.

Frailty, cognitive decline, loss of vision and hearing, and decreasing dexterity make it difficult to go to a grocery store, purchase food, transport the food home and prepare a meal. A lack of cooking skills, difficulty preparing meals and observing food safety rules can hinder eating regular healthy meals.

Meal quality: Since all functions decline in high age the gastrointestinal tract is not an exemption. The ability to properly digest foods and extract nutrients decreases due to gastrointestinal decline in old age. On the other hand energy requirements are lower. Therefore, nutrient-dense meals become essential. Healthy nutrient-rich meals can counter age-related inflammation, provide sufficient amounts of protein to counter the loss of muscle mass and provide the energy to support daily physical activity. Quality meals also need to have an enjoyable flavor and texture to stimulate eating adequate amounts.

Mealtime Experience: Nutrition professionals tend to focus on food quality and quantity but with increasing age it is important to consider the mealtime experience as well. The best tasting, healthiest meal is not enjoyable if all meals are eaten alone. As we all know companionship during a meal allows us to enjoy meals and therefore eat sufficient amounts of food. Lonely eaters are more likely to eat less.

One hallmark of aging is the loss of resilience. Stress and loneliness can affect older individuals more severely and depression develops. Low mental health can discourage from regularly consuming balanced meals or partaking in physical activity.

Excessive fatigue may also impact the ability to eat. This may mean that the individual has to rely on someone else to prepare food or feed them. Being fed reduces agency how, what and when to eat. The same principle applies to fluid consumption. Some older individuals may not be able to access fluids easily or intentionally decline fluids to reduce the amounts of times they use the bathroom since they need assistance to complete each of these tasks.

The mealtime experience can change immensely due to chronic diseases. Taste and appetite can change profoundly in seniors dealing with age related diseases. In addition, illnesses such as stroke or loss of teeth can reduce the ability to chew and swallow making meal times a stressful time of the day. Diseases resulting in restrictive diets may also make finding palatable foods more difficult.

Anorexia Of Aging Fuels Malnutrition, Sarcopenia and Frailty

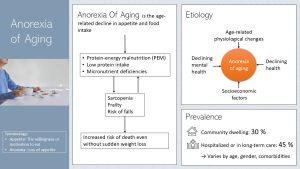

One major factor resulting in malnutrition is the development of anorexia of aging. You might have heard about the eating disorder anorexia nervosa. The term anorexia is defined as the abnormal loss of the appetite for food. Appetite is the body’s willingness or motivation to eat and is our main driver to maintain adequate energy intake.

While many aging individuals will have a healthy appetite around 30 % of community dwelling and 45 % of people in long-term care struggle with anorexia of aging.

Anorexia of aging is the age-related decline in appetite and food intake. This can lead to skipping meals or eating only very small amounts of food. Either way energy and nutrient intake will become inadequate.

As anorexia progresses the reduced food intake will lead to protein-energy malnutrition (PEM). PEM, a condition marked by low protein and energy intake, results in rapid weight loss, muscle wasting, and fatigue and weakness. The inadequate protein and micronutrient intake will result in declining metabolic function and increased risk for disease.

Anorexia of aging accelerates the development of sarcopenia and frailty. The risk for falls increases. Falls in older adults are serious and can lead to fractures and head injuries. Falls can start a cascade of socioeconomic (medical costs) and health consequences (sarcopenia, frailty, cognitive decline). In addition, recurrent falls may result in the fear of returning to daily activities. Independence and quality of life is lost. Unintentional falls are the leading cause of injury-related death in people over 65 years of age.

The etiology of anorexia of aging is multi-factorial. Age-related physiological changes impact each person differently depending on lifestyle and genetic predisposition. Declining health—physiological and mental—can trigger the loss of appetite and drive to eat. As discussed above socioeconomic factors alter meal access, quality and experience which in turn can lead to a loss of appetite. Health care providers should explore what factors contribute to the development of anorexia of aging of an individual person.

Physiological Changes Impacting Appetite Make Seniors Vulnerable to Malnutrition

When Eating Difficulties Develop Meals Become Stressful and Appetite Decreases

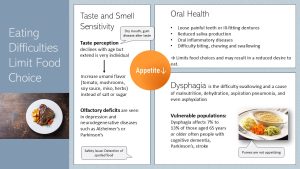

Taste and smell: Part of the aging population will experience a decline in taste and smell perception. However, it is unclear if this decline will happen in healthy aging. It is more likely that this decline is connected to age-related chronic diseases. Olfactory functioning is necessary for a rich flavor experience during a meal. Olfactory decline is seen mostly in depression and neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease.

No matter the reason, bland tasting food is not enjoyable. Many try to counter the blandness by adding more salt and sugar, but this approach may lead to an aggravation of existing chronic diseases such as hypertension and insulin resistance. Instead, the savory, meaty and brothy flavor of food called umami should be enhanced. Adding tomato paste, mushrooms—especially dried and powdered—and herbs during the cooking process can accomplish this. Instead of salt, small amounts of miso paste and soy sauce will add the salt in combination with lots of umami flavor.

Oral health: Difficulty biting and chewing develops with lose and painful teeth, loss of teeth, or ill-fitting dentures. Harder to chew foods such as steak, crunchy snacks and vegetables might not be an option anymore. Reduced saliva production will make it difficult to move food around in the mouth during chewing resulting in a dry and tough food texture that is difficult to swallow. Oral inflammatory disease such as inflamed gums make biting and chewing painful. Limited food choices and stressful chewing and swallowing will take the fun out of eating.

Dysphagia: Imaging that you struggle to swallow bites of food or even sips of liquids. The struggle and fear of asphyxiating can make the meal to the most stressful time of the day. The difficulty swallowing is called dysphagia and is a major cause for malnutrition, dehydration, pneumonia and even asphyxiation.

Dysphagia affects about 7 to 13 % of the aging population. The most common cause for dysphagia is dementia, Parkinson’s disease, cancer, and stroke. Another cause for dysphagia is sarcopenia of the lingual musculature.

Dysphagia can be easily overlooked and the affected person slips rapidly into malnutrition. A speech pathologist can conduct a swallow study and determine appropriate treatment. This can include tongue strengthening exercises and a collaboration with a clinical dietitian who changes the consistency of foods to match swallowing ability.

Dysphagia diets have multiple levels including pureed, mechanically altered, and soft foods. Individuals with dysphagia may also need liquids thickened in order to prevent aspiration.

Eating only pureed or semi-liquid food is not enhancing the enjoyment of eating. Recently, 3-D printing enables dietitians to design foods that are adequate for the swallowing difficulties but look more visually appealing.

Gastrointestinal Changes Increase Satiety

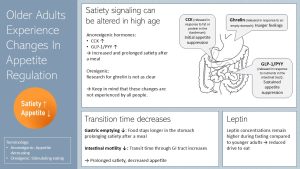

Intestinal hormone secretion: So far, the factors impacting appetite you studied are connected with the hedonic side of energy intake regulation. During the last decades scientists also started to understand the physiological side of appetite regulation in high age (homeostatic pathway).

When you start eating your meal the gastrointestinal tract starts excreting several hormones that have two functions. First, the hormones coordinate digestion (paracrine secretion). Second, the hormones circulate the blood stream and reach the hypothalamus in the brain. This endocrine secretion regulates satiety.

Ghrelin is released by the stomach if the last meal is a while ago and the stomach empty. Ghrelin—the only orexigenic hormone—stimulates food intake. When we start eating ghrelin secretion subsides.

Once fat and protein leave the stomach, the duodenum secretes anorexic hormones. Rising CCK blood concentrations trigger a first wave of appetite suppression. As nutrients are further digested and reach the distal intestine the hormones GLP-1 and PYY are secreted initiating a sustained appetite suppression. After food is digested and nutrients absorbed and stored, the anorexigenic hormones are enzymatically degraded. This allows you to develop appetite for the next meal.

People experiencing anorexia of aging tend to have increased CCK, GLP-1 and PYY secretion after a meal and a reduced degradation of those anorexigenic hormones. Higher and prolonged blood concentrations increase and prolong satiety after a meal. Smaller meals are eaten or meals are altogether skipped.

Research for ghrelin is less clear. While some studies report higher ghrelin secretion, others report lower secretion. Keep in mind that these changes are not experienced by all aging people. Many will retain a healthy appetite into high age.

Gastrointestinal transition time: During aging gastrointestinal transit time slows down, and enzyme activity decreases. Since gastrointestinal emptying is delayed food stays longer in the stomach. Some studies also show that less food extends the stomach faster.

Slower passage due to reduced intestinal motility and lower enzyme activity in the small intestine leads to prolonged nutrient contact with the intestinal epithelium. This might be the cause for the increased hormone secretion. In addition, the slower passage of the food through the GI tract and decreased enzyme activity can cause issues such as constipation.

One more physiological change: The hormone leptin is secreted mostly by the adipose tissue and contributes to the long-term regulation of energy intake. In younger adults leptin secretion is proportional to the amount of adipose tissue. If a younger person loses weight leptin secretion is lowered and triggers an increased drive to eat. In older people leptin secretion during fasting remains higher which means that the drive to eat is reduced despite fat loss.

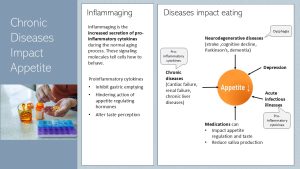

Chronic Diseases Impact Appetite

As discussed in chapter 30 cellular aging increases low-grade chronic inflammation even in people with a healthy lifestyle. This specific type of inflammation is called inflammaging.

Accumulating cellular garbage—misfolded proteins the cell removes only inefficiently in high age—triggers the innate immune system which in turn secretes pro-inflammatory cytokines. Higher concentrations of these signaling molecules are now circulating the blood stream and alter how cells function.

Pro-inflammatory cytokines slow down gastric emptying, hinder appetite regulating hormones and alter taste perception.

So far most of the appetite-altering physiological changes can take place in many healthy individuals. Diseases accelerate anorexia of aging.

Neurodegenerative diseases can result in dysphagia. Chronic diseases increase the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines even more. Older individuals are more vulnerable to infectious diseases. Catching a cold or the flu can be a major setback.

Many medications impact appetite or saliva production. Lastly, mental health has also a major impact on appetite.

It becomes clear, that older individuals with chronic disease are much more at risk to develop anorexia of aging compared to individuals with a lifelong healthy lifestyle.

One more idea to think about: There might be medical reasons for changing the diet such as declining heart or kidney function. Individuals with heart issues might be required to consume low amounts of sodium and fat. Individuals with chronic kidney disease need to restrict protein. Others might be on carbohydrate restrictive diets due to diabetes. Diets due to medical reasons can make finding appetizing foods more difficult.

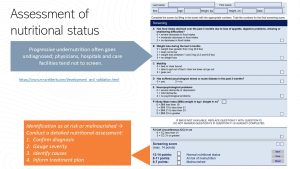

Nutritional Status In People Over Age 65 Can be Measured With the Mini Nutritional Assessment

The first step in preventing and treating malnutrition is to assess the nutritional status. The Mini Nutritional Assessment or MNA® is a screening and assessment tool used for individuals over the age of 65 who are at risk or currently experiencing malnutrition. It was originally developed in the 1990s and has evolved over time. Screening time should take only 5 minutes.

If the result of the MNA®-Short Form indicate malnutrition or a risk for malnutrition a dietitian can conduct a full nutritional assessment to confirm the diagnosis, assess the severity, identify the causes and start a treatment plan.

What Can Seniors Do to Prevent Eating Difficulties and Reduce the Risk For Chronic Diseases?

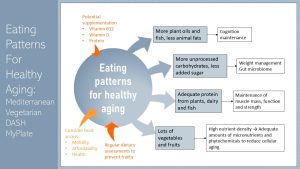

A Diet For Seniors Should be Nutrient Dense and Provide Adequate Amounts of Protein

Is there an optimal diet for older people? Scientific research supports the Mediterranean diet. Rich in fruits, vegetables, legumes and whole grains the Mediterranean diet is nutrient packed and provides plenty of nutrients with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. Adding fish and nuts will provide good amounts of omega-3 fatty acids. The smaller amounts of dairy, eggs, poultry and meat, and ample consumption of olive oil shift the fatty acid profile of this diet to a heart healthy one. The problem is that the Mediterranean diet is not culturally acceptable to everybody. How can we combine the benefits of the Mediterranean diet with a familiar, culturally acceptable eating pattern?

Lots of fruits and vegetables: A diet for seniors needs to provide adequate amounts of micronutrients while avoiding empty calories. A eating pattern rich in plant-based foods increases nutrient density and reduces energy density. This will allow for healthy weight maintenance. Plenty of plant-based foods will provide nutrients with antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. Those nutrients will soften the age-related low-grade chronic inflammation.

Adequate protein: Maintaining muscle mass, function and strength is essential for healthy aging. A mix of animal and plant-based proteins spread out over the day are recommended. Fish, dairy (if tolerated), and plant protein sources such as legumes and nuts are easier to chew and might be an option. Protein supplements might be considered to reach an adequate protein intake.

Dietary fats: Increasing plant and fish oils while decreasing animal fats is associated with better cognition maintenance.

More unprocessed carbohydrates, less added sugar: Increased intake of fiber is important to prevent constipation and maintain a balanced gut microbiome. Maintenance of the gut microbiome is essential to limit low-grade chronic inflammation and is also discussed with better cognition.

This type of diet can be expensive. Counseling by a dietitian can identify inexpensive foods and recipes, and identify resources to buy healthy foods.

Water, Protein, Vitamin B12, Vitamin D and Omega-3 Fatty Intake Need Special Attention

The corner posts of eating in advanced age is a nutrient dense, plant-heavy diet and adequate protein intake. In addition, there are four nutrients that might need special attention due to age-related physiological changes.

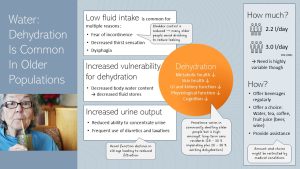

Dehydration is common in older people. According to a literature review (Li et al, 2023) the prevalence of dehydration in community-dwelling individuals ranges widely from 1 – 60 %. Amongst long-term care residents dehydration seems to be the norm though. Around 28 – 30 % of individuals are at the brink of dehydration and an additional 20 – 38 % have existing dehydration. Even if the prevalence varies and determining dehydration is tricky the data shows that dehydration in older populations is a serious problem.

Dehydration impacts health and well-being. As dehydration sets in, metabolic health declines and degenerative diseases of old age are aggravated. Skin, gastroinstestinal and kidney health are negatively affected. Physiological and cognitive function decline. Studies show that re-hydration can improve function, health and well-being.

Why are older people especially vulnerable to dehydration? The situation is multifactorial and it is important to assess what factors affect each individual person.

Body composition: As people age body water content declines. This means that the older person has decreased fluid stores to balance out variation in water intake. Dehydration sets in faster.

Low fluid intake: This is common for a variety of reasons. Many older people experience reduced bladder control. Going to the bathroom might also require assistance and time. Reducing fluid intake will reduce bladder leaks and frequent bathroom trips, but can result in dehydration. In high age thirst sensation can decrease which will require more intentional drinking. Lastly, some older people with neurological disorders develop dysphagia. This effects not only the swallowing of food. Drinking can be impaired which might require thickening of beverages.

Increased urine output: Renal function declines with age. Reduced filtration by the kidneys might reduce the ability to concentrate urine. More fluid is excreted. Some medications such as diuretics and laxatives can also increase the fluid output. This increased output needs to be compensated by increased fluid intake.

How much should older people drink. The IOM recommends that men drink 3 l per day and women 2.2 l per day. The actual need is variable though depending on fluid output.

Recommending an amount tends to be the easier side of things. How can older individuals be encouraged to drink more? Especially in assisted living centers beverages should be easily accessible and offered regularly. A choice of beverages such as water, tea, coffee, fruit juice and even alcoholic drinks such as beer allows the individual to enjoy drinking. Keep in mind though that the type of beverage might be restricted due to medical conditions. For example, older individuals with type-2 diabetes should not drink sugary beverages such as fruit juice.

Most importantly, older people might need assistance drinking and going to the bathroom.

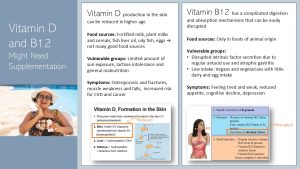

Most of the vitamin D we need is produced in the top layers of the skin during sun exposure. Food sources for vitamin D are slim and only fish and eggs contain naturally good amounts of vitamin D. The remaining food sources are vitamin D fortified foods such as milk, plant milks, and cereals.

With age the ability to produce vitamin D in the skin becomes less efficient. Daily use of sunscreen, sometimes integrated in lotions and creams, reduces the vitamin D production as well. In addition, frail seniors might not spend a lot of time outdoors in the sun. More food vitamin D is needed to compensate, but milk, the main source of vitamin D, might not be consumed due to lactose intolerance.

Vitamin D deficiency causes a variety of issues. As it is essential for calcium absorption, deficiency in vitamin D limits the amount of calcium that can be absorbed. During midlife bone density starts to decline slowly (see chapter 30). Vitamin D deficiency accelerates the natural boneloss. Bones become brittle and the risk for osteoporosis and fractures increases. Research also links vitamin D deficiency to muscle weakness and falls, decreased cognition and increased risk for cardiovascular disease and cancer.

Vitamin B12 is another nutrient of concern. Around 20% of seniors have mild vitamin B12 deficiency that results in neurological symptoms similar to early dementia. Symptoms include memory loss, lack of physical coordination, vision problems, and difficulty speaking. A blood sample allows to diagnose pernicious anemia, one clinical symptom of vitamin B12 deficiency.

The risk for mild vitamin B12 deficiency is related to the common chronic inflammation of the stomach lining in older adults, atrophic gastritis. Stomach ulcers and certain medications can also cause issues in absorption.

Why is vitamin B12 more susceptible to digestion and absorption issues in high age? The digestion mechanism of vitamin B12 is very complex and involves several steps as you see on the slide above. The key step impacting vitamin B12 absorption in old age is a reduced production of intrinsic factor by the parietal cells in the stomach. If the stomach lining is chronically inflamed the secretory function of stomach cells declines. Over time the chronic inflammation will lead to replacement of healthy stomach tissue with fibrous tissue.

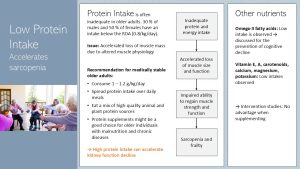

Protein intake in older adults will need special attention. While most Americans tend to eat plenty of protein the usual protein sources such as meat and poultry might be harder to eat due to eating problems. In addition, some older individuals experience food preference changes that decrease their appetite for meat. It is estimated that 30 % of older men and 50 % of older women have an inadequate protein intake.

The first question is if the currently recommended intake of 0.8 g/kg/d is sufficient for people over 65 years of age. Building and maintaining muscle will require exercise in combination with amino acids to stimulate muscle building. Studies show that the muscle of older adults is less responsive to low amounts of amino acids. This lack of responsiveness in older adults can be overcome with slightly higher levels of protein. Therefore, many scientists recommend to increase protein recommendations to 1-1.2 g/kg/d in order to maintain adequate muscle mass. Keep in mind that this is a subtle increase equating at most one deck-of-card serving of chicken.

For the same physiological reason regaining muscle mass after it is lost is more difficult as well. For example, an older person contracting the flu in winter will need to rest often for weeks. The reduced physical activity will trigger loss of muscle mass. After the person has recovered it will be difficult to get back to the full muscle mass, strength and function.

In addition to the higher intake recommendations, it is also recommended to eat some of the protein as animal-based protein. This can be fish, poultry or meat but also dairy and eggs. Since digestion and absorption of meat is also reduced the protein should be spread out over meals.

For individuals with malnutrition and chronic diseases a protein supplement might be a good choice.

When you look at social media posts protein recommendations follow the theme the more the better. High protein intake might have a negative impact on older adults. Many older people have impaired kidney function. Most don’t even know about that. High protein intake in people with impaired kidney function will stress the kidneys and lead to an accelerated decline of kidney function. This means that we have to walk a fine line between adequate protein intake while avoiding excess.

While maintaining muscle mass is essential for a long quality life, amino acids have other metabolic functions. This includes cognitive health, immune system, wound healing and bone health. Inadequate protein intake will impair the immune system and wound healing which could mean increased hospitalization time which is in itself a factor contributing to an increased risk for malnutrition. Cognitive decline is one of the factors accelerating frailty.

Lately omega-3 fatty acids made it on the list of special attention nutrients for seniors. This is related to newer research showing that adequate consumption of omega-3 fatty acids might help maintain brain health and cognitive function, and improve age-related chronic systemic inflammation. Fatty fish consumption, the main source for omega-3 fatty acids is not common in landlocked parts of the US and plant sources seem not to be as effective when it comes to cognition.

Studies also show that older people with malnutrition have an inadequate nutrition status for a range of other nutrients. Supplementation of all these nutrients, especially if food intake is low, may be necessary to maintain adequate supply in the body.

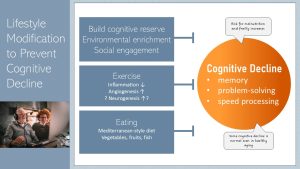

Can a Healthy Lifestyle Prevent Or Slow Cognitive Decline?

During the last two decades studies accumulated substantial evidence that a poor diet rich in fat and sugar, obesity during midlife and type 2 diabetes are associated with an increased risk to develop dementia in old age. The physiological and molecular mechanisms are not as well understood at this time but animal studies suggest that increased inflammation and altered gut microbiome composition seem to explain the association.

Some cognitive decline can be expected even in healthy individuals which makes it important to build cognitive reserve over a lifetime. Very similar to bone and muscle mass, the higher the cognitive abilities at peak the less we will notice the age-related cognitive decline. Cognitive reserve is build when a healthy lifestyle meets education, lifelong learning and the ability to work through complex problems.

Not all cognitive function is affected equally by the aging process though. Most alterations are seen in cognitive functions located in the hippocampus. Memory function is most affected followed by problem-solving skills and speed processing. There is currently no pharmacological treatment for cognitive decline, but a stimulating environment, a healthy diet, and plenty of exercise can prevent rapid loss. Some studies suggest that a healthy diet such as the Mediterranean diet can even improve cognition slightly.

What else can an older person do to improve cognition or prevent rapid decline? One of the simplest ways is environmental enrichment. This involves activities that stimulate the learning of new skills such as painting, playing musical instruments or reading. Stimulating hobbies can be started at any age . Those with higher levels of education or people speaking more than one language show resistance to memory decline.

Another way to reduce the risk of cognitive decline is through regular exercise. Aerobic exercise improves hippocampal memory function at any age. Again, we see the association but are not fully sure what causes this. Cardiorespiratory fitness, increase of blood vessels and nerves in the brain?

While less researched, high social engagement is correlated with hippocampal health. Group interaction seems to be more beneficial than individual relationships. As previously mentioned, regular interaction with others decreases the risk of depression, which can impair cognitive abilities.

Ensuring that the older person continues to take care of body and mind through diet, exercise, and environmental enrichment decreases the risk of malnutrition, frailty, and overall decline of function.

Interested in More Information?

Poverty Among the Population Aged 65 and Older (April 2021)

Rodríguez-Mañas L, Murray R, Glencorse C, Sulo S. Good nutrition across the lifespan is foundational for Healthy Aging and Sustainable Development. Frontiers in Nutrition. 2023;9. doi:10.3389/fnut.2022.1113060

Editor: Sydney Christensen

NUTR251 Contributors:

- Spring 2020: Julia Curtis, Madison Yourstone, Haley Jensen, Brittany Southall, Julia Curtis, Gage Gauchat, Kalen Codr, Amelia Johnson, Hailie Slepicka, Shane Rapp, Kyle Dawson

- Fall 2020: Kaitlyn Higgins, Pierce Krouse, Carly Schwager

Misfolded proteins the cell is not able to clear away

A hormone (mostly) secreted by the adipose tissue. Leptin signals the status of the energy stores in the adipose tissue to the brain and other organs. Declining fat stores result in declining leptin secretion and vice versa.

A condition characterized by the gradual loss of muscle mass, strength, and function

A medical condition characterized by a loss of reserve and function making people excessively vulnerable to stressors

Related to the sense of smell

Cell to neighboring cells

Signaling to other tissues and organs

Stimulating eating

first part of the small intestine that is connected to the stomach

Reducing appetite

Cholecystokinin

Glucagon-Like Peptide-1

Peptide YY

The coordinated contractions and relaxations of the muscles in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract that propel food and waste products forward

Feedback/Errata