10 Healthy Eating Before Conception Prepares For a Healthy Pregnancy

Sabine Zempleni; Eric Hanzel; and Sydney Christensen

You have probably seen the glowing Instagram posts of women who will happily tell the world that they are finally pregnant. In an ideal world, women and men would prepare for pregnancy by adopting a healthy lifestyle and start taking a prenatal folate supplement.

Looking at CDC data it becomes clear that for most prospective parents this is not the case. In 2011, 45% of pregnancies were unintended. In addition, specific groups of women have an even higher prevalence for unintended pregnancies. For teens this number was 75%. Other groups with high unintended pregnancies

- Were aged 18 to 24 years.

- Had low income (<100% of federal poverty level).

- Had not completed high school.

- Were non-Hispanic Black.

Why is this important? Women with unintended pregnancies are more likely to start prenatal care late or receive inadequate prenatal care. Women may also go into the pregnancy without an overall healthy lifestyle and partake in unhealthy habits such as smoking and alcohol consumption. It is not a surprise that unintended pregnancies more often lead to premature birth or low-birth-weight infants.

If the pregnancy is intended, most mothers prepare. They give up smoking, alcohol, and caffeine. Those measures definitely increase the likelihood for a smooth, healthy pregnancy, but there are nutritional factors left that are often not addressed: Weight and intake of some select nutrients.

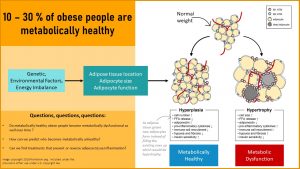

Before working on this chapter, it is important to recall the connection between obesity and metabolic health:

You Will Learn:

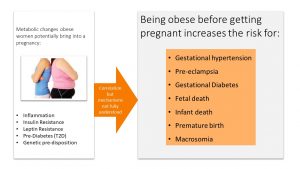

- Obese women might be metabolically healthy, but chances are that they bring low-grade chronic inflammation, insulin resistance, and leptin resistance into the pregnancy.

- Obesity during pregnancy increases the risk for negative pregnancy outcomes for mother and child:

- Preeclampsia is the most feared pregnancy complication. The risk increases with increasing maternal weight.

- The risk for preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, and gestational hypertension is connected to the pre-pregnancy BMI.

- Underweight before pregnancy does not impact mother and child negatively as long as the woman gains sufficient weight during pregnancy.

- While additional weight can be gained in underweight, excessive weight should not be lost during pregnancy. Therefore, overweight needs to be addressed before pregnancy.

- Low intake of folate, iron, and vitamin B12 needs to be addressed before pregnancy to ensure a healthy fetus.

Obese Women Might Be Metabolically Healthy, but Chances Are That They Bring Low-Grade Chronic Inflammation, Insulin Resistance, and Leptin Resistance Into the Pregnancy.

Unless a woman has a genetic predisposition for chronic diseases, obesity is not necessarily connected to metabolic dysfunction in young women. As women get older and reach their late twenties, thirties or even forties, metabolic dysfunction increases.

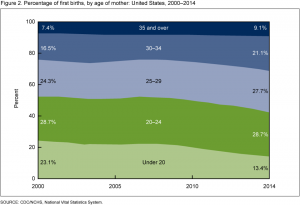

In the 1980s, most women gave birth to their first child in their early 20s. Today, many women delay pregnancy and focus on their career during their 20s. The CDC graph (right) demonstrates that pregnancies in young women have declined, while more pregnancies take place during the second half of the reproductive years.

This is a health concern because an unhealthy lifestyle is common and obesity rates hover around 30% in women in the reproductive years.

Increasing obesity rates and the delaying of pregnancy leads to more women bringing moderate metabolic dysfunction into a pregnancy. The woman might not have a diagnosed chronic disease, but undiagnosed insulin resistance, leptin resistance, and low-grade chronic inflammation might be present. Keep in mind that normal weight women can also have metabolic dysfunction if they have high amounts of visceral fat in their stomach cavity, and that many overweight and obese women will have a healthy pregnancy.

This is not a hypothetical concern. Research shows that being obese before a pregnancy increases the risk of developing dangerous pregnancy complications such as gestational hypertension, gestational diabetes, or preeclampsia. When the research looks at the fetus, the risks for premature birth, macrosomia (exceptionally large newborns), and fetal death increases if the mother goes into pregnancy obese.

The increased prevalence of those pregnancy complications contributes, along with other factors, to the high maternal death rate in the United States. Research is under way to understand the connection between obesity, maternal age, pregnancy complications, and maternal death. Here is what we know so far.

Obesity During Pregnancy Increases the Risk for Negative Pregnancy Outcomes for Mother and Child

Preeclampsia Is the Most Feared Pregnancy Complication. The Risk Increases with Increasing Maternal Weight.

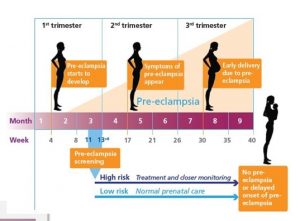

Preeclampsia is the leading cause for maternal and infant death in the US and worldwide. Pregnant women are monitored closely during their prenatal visits, but sometimes preeclampsia develops so fast that the pregnant woman goes from happy and healthy to having a life-threatening emergency. The key to preventing preeclampsia is properly preparing for pregnancy, even before it has occurred, and being knowledgeable of preeclampsia symptoms so the symptoms are not missed.

Watch this YouTube video first:

Preeclampsia occurs in 5-8 % of pregnancies after 20 weeks of gestation, but can also occur within 6 weeks after birth (postnatal preeclampsia).

For some women, the only symptoms are high blood pressure and protein in the urine. This is regularly checked during prenatal check-ups. At the beginning of the second trimester, the pregnant woman is screened for preeclampsia risk. If the risk is determined as high, the obstetrician will monitor the woman very closely.

For some women, the first symptoms of preeclampsia might show up in the middle of the second trimester. Other women pass the preeclampsia screening with flying colors and do not have any symptoms until they have sudden head splitting headaches and a swollen face. Another group of women have a healthy, happy pregnancy, take a healthy baby home, start their life as a family, then develop sudden pre-eclampsia symptoms weeks after the birth. This unpredictability of preeclampsia onset makes the condition so dangerous.

Any of the following symptoms should send a pregnant woman immediately to a physician, and if the symptoms are severe enough, to an emergency room:

- High blood pressure

- Proteinuria

- Edema (Face, hands, eyes)

- Abdominal pain

- Headaches

- Nausea or vomiting

- Sudden weight gain

- Changes in vision

- Shortness of breath

Uncontrollable risk factors for preeclampsia are genetic predisposition for high blood pressure and age. The risk for preeclampsia is greatest for teenagers and women over 40. Controllable risk factors are weight and lifestyle.

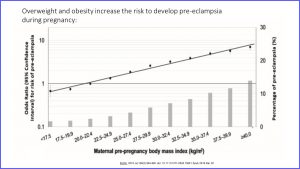

Here is the result from a study concerning weight and preeclampsia risk. On the x-axis you see the maternal pre-pregnancy BMI. The dots and line measure risk of preeclampsia. As the line goes up the risk increases. The bars depict the percentage of women developing preeclampsia in each weight group. The higher the weight, the more cases of preeclampsia. Once women reach a BMI between 35 and 40 (class I) or over 40 (class II) more than 10% are likely to develop preeclampsia during pregnancy.

The Risk of Developing Gestational Diabetes and Gestational Hypertension is Connected to Weight and Metabolic Health

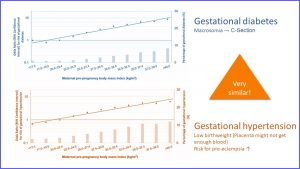

The same study also investigated the risk for gestational diabetes and gestational hypertension. The picture is very similar:

Gestational diabetes and gestational hypertension are treatable but present a health risk to mother and fetus. With increasing pre-pregnancy weight, gestational diabetes and hypertension become more common.

If left uncontrolled, both gestational diabetes and gestational hypertension can cause problems in a pregnancy. Gestational diabetes will result in extremely large newborns. A c-section might be necessary and the large newborn will likely have health issues after birth. Gestational hypertension is connected to a low birth weight and increases the risk for preeclampsia. We will discuss this topic further in the pregnancy chapter.

As mentioned previously, unintended pregnancies are prevalent in the United States, and women who start prenatal visits late or do not have access to healthcare at all, are at an even higher risk for these types of pregnancy complications. In addition to the obesity prevalence, limited access to healthcare could also explain the high maternal death rates in the US.

Underweight Before Pregnancy Does Not Impact Mother and Child Negatively as Long as the Woman Gains Sufficient Weight During Pregnancy

Half of the women in the US that are getting pregnant are overweight, and for black women, this number is even higher—75%. Being overweight or obese, as you have seen, increases the risk for preeclampsia, gestational hypertension, and gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM). This explains, in part, the extremely high maternal mortality rate for a developed country.

What if the woman is underweight going into a pregnancy?

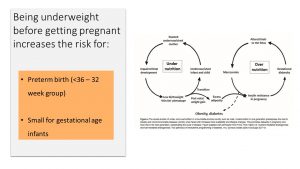

First, the good news: Underweight, unlike obesity, is not associated with the dreaded pregnancy complications such as GDM, gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, and consequently c-section. Maternal and infant mortality is not increased.

There are other negative pregnancy outcomes, affecting mostly the baby, that are associated with an underweight pre-pregnancy BMI. These negative outcomes can be averted as long as the pregnant woman gains sufficient weight during the pregnancy.

This means that we should focus on risk groups that are underweight and likely to delay or forgo prenatal visits. In the US, these risk groups include teens, athletes, and women who chronically diet. Note that while poverty in the US is usually associated with overweight, in developing countries underweight is associated with poverty.

Underweight mothers who do not gain sufficient weight during pregnancy are more likely to give birth to small for gestational age (SGA) infants.

Underweight mothers who do not gain sufficient weight during pregnancy are more likely to give birth to small for gestational age (SGA) infants.

They are also at risk for premature birth. The good news here is that premature delivery tends to not be extremely early, threatening the life and health of the newborn (micro-preemies), but rather between weeks 32 and 36 when the fetus is mature enough to breathe and feed.

Another concern relates back to what you learned during the epigenetics chapter. Underweight mothers might trigger epigenetic adaptations that set up the fetus for a thrifty metabolism and increased risk for chronic diseases later in life. When SGA babies are born, they tend to go through a rapid catch-up growth after birth. This rapid growth after birth is linked to obesity during childhood and adulthood. If the child becomes an obese adult, then chances are that the fetus in this pregnancy is born overly large and at risk for obesity and metabolic syndrome. In this way, both underweight and overweight fuel the obesity epidemic via fetal programming.

Underweight women might want to gain some weight, but the focus should be much more on eating healthy, regular meals. This will make sure that nutrient stores are replenished before pregnancy.

Fetal Programming

There is compelling evidence that maternal undernutrition and overnutrition during pregnancy programs the fetus for a phenotype that increases their vulnerability for obesity and metabolic syndrome later in life.

Newer studies show that obesity can be programmed via alterations in DNA methylation. At this point there is less evidence for histone modification. Examples for those alterations are the hypomethylation of the DNA coding for IGF2, a hormone that directs fetal growth and metabolic regulation, leptin gene methylation, genes regulating adipogenesis and the brain appetite/satiety reward pathways. In addition to the maternal weight status, alterations were also found for paternal obesity, excessive weight gain during pregnancy and GDM. As already mentioned in the epigenetic chapter some of these epigenetic alterations, especially if they take place during sensitive periods, can be transgenerationally inherited.

The good news is that epigenetic alterations can be reversed, and animal studies demonstrate this clearly.

Healthy Eating and Exercising Should Be Established Before Conception

Weight Loss Before Conception Will Improve Metabolism and Reduce Pregnancy Risks

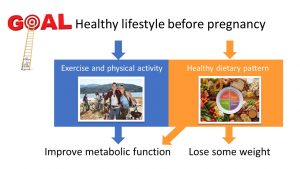

While underweight women can address their low weight effectively during pregnancy, the situation is not as easy for obesity. Pregnant women, in general, should not diet or lose substantial amounts of weight. You will learn the physiological reasons during the pregnancy chapter.

Women might want to stay away from trendy diets and use the incentive of a healthy pregnancy to learn how and where to start when implementing a healthy lifestyle.

- Eat a plant-heavy mixed diet as recommended by MyPlate.

- Improve metabolic function by increasing physical activity and exercising.

- Reduce obesity as much as possible. 5 – 10% weight reduction tends to improve metabolic health and fertility, but the closer the weight to a normal BMI the higher the probability that the pregnancy is a healthy one.

Improving metabolic health, in both the woman and man, will work two ways. Fertility is improved and more importantly conception will take place between two high-quality gametes. This will ensure a healthy embryo and placenta and reduces the risk for pregnancy loss. Secondly, metabolic health will promote healthy fetal programming and a lower risk for pregnancy complications.

Low Intake of Iron, Folate, and Vitamin B12 Needs to Be Addressed Before Pregnancy

Pregnancy requires some special attention to micronutrient consumption. Even if a woman is following a generally healthy lifestyle, she may not be consuming enough of these nutrients to maintain her health status through pregnancy. That is why it is important that women who could potentially become or are planning on becoming pregnant consider taking a prenatal supplement.

The following are the three key micronutrients:

- Iron

- Folate

- Vitamin B12 (only: vegans and vegetarians with very low dairy and egg consumption)

While it is important that women consume a variety of vitamins and minerals, deficiencies in these three micronutrients are common in young women and may cause most of the problems during a pregnancy.

It is important to take note of for those three nutrients deficiencies may not cause clear symptoms in the woman, but the deficiency or suboptimal intake will be detrimental to the fetus. In addition, it is difficult to correct these deficiencies pregnancy, making it essential that women address a suboptimal intake before pregnancy.

Iron

Iron Deficiency Takes Time to Correct

Why do I highlight iron? Many American women also under consume vitamin A, C, D, E, the minerals magnesium and potassium, and fiber. This can be corrected with a healthy diet or a prenatal supplement very easily.

Iron is different. If a person has a low iron status—it would not even take full anemia—an iron supplement is recommended.

Here is the problem. This supplement needs to be taken properly in order to return iron stores back to normal as fast as possible. This includes taking the supplement with sources of vitamin C, such as orange juice, and avoiding calcium rich foods (dairy) and tea during the meal when the supplement is taken.

If the supplement is taken properly, iron blood levels will start rising in the second week, but it will take up to 3 months to return to sufficient iron stores. Pregnant women expand their blood volume and grow new tissue. Tissue growth requires iron, which increases the iron need throughout pregnancy. This makes it even more difficult to have sufficient iron stores during pregnancy if a woman starts out anemic.

In addition, many women have problems with a sensitive stomach during the beginning of the pregnancy, as they may suffer from morning sickness. Iron supplements tend to aggravate the gastrointestinal tract, adding to the morning sickness problem.

For all those reasons it takes time to fix iron deficiency anemia during pregnancy. During this time the fetus is not supplied adequately with iron.

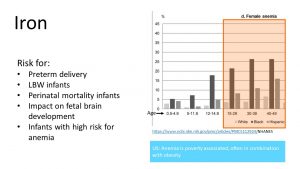

It is also important to understand that the prevalence of anemia reflects a health disparity. The graph on the right shows that around a quarter of premenopausal Black and 10-15% of Hispanic women are anemic. In the US, anemia is most often associated with poverty and obesity, which tend to be correlated. Energy rich food with little nutrient density is common in poverty and contributes to obesity. It is also thought that metabolic alterations due to excess adipose tissue might contribute to anemia in obesity. Since white American women have a lower prevalence of poverty and obesity, anemia is less common in white women.

Iron is an extremely important nutrient during pregnancy and is monitored carefully during prenatal visits. If a pregnant woman is anemic, she will be at risk for preterm delivery or a newborn with a low birth weight. The risk for the death of the infant right before or after birth increases.

Even if the infant is born at term and seemingly healthy, new studies show that there is a connection between low iron stores in the newborn and less than optimal brain development.

This makes it extremely important that iron deficiency anemia is corrected before conception.

Black and Hispanic Women Are the Most Vulnerable for Low Iron Status or Iron Deficiency

According to the previous graph between 5-25% of pre-menopausal women are anemic. This makes it important to identify and educate vulnerable groups of women:

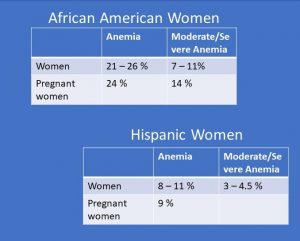

The first vulnerable group are black and Hispanic women.

This study of 776 pregnant women showed that almost a quarter of pre-menopausal black women have anemia and around 10% have severe anemia before pregnancy. During pregnancy the level of moderate to severe anemia increases to 14%. The study discusses that this health disparity might stem from a higher proportion of poverty in the black community and a lack of access to health care before and during pregnancy.

Hispanic women are the second most vulnerable group for anemia. The prevalence for anemia is not quite as high but still higher than white and Asian women.

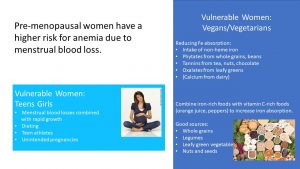

There are two more vulnerable groups: teenage girls and women on a vegan or vegetarian diet.

Women beyond menarche and prior to menopause are at a high risk of iron deficiency due to menstrual blood loss. Teenage girls are at risk for iron deficiency because of the onset of menarche as well as an increased need for iron to support their continued growth and expansion of red blood cells. Adolescence is also a time when many teens focus less on healthy eating which can ultimately lead to an iron deficient diet.

Iron deficiency, with and without anemia, is also prevalent among female athletes and is thought to be due to a combination of diets deficient in iron and small blood losses from the GI tract, urine, and sweat from intensive training. These losses may be small and unnoticeable, but overall can contribute to an increased need for iron.

Vegetarians and vegans are also at risk because they do not consume meat, poultry, and fish. These animal products are the source for heme iron which has a bioavailability of 14% to 18%. Bioavailability in plant sources, called non-heme iron, is 5% to 12%.

The main iron sources in plants are whole grains, legumes and some greens. Phytates in whole grains and beans, tannins in tea, nuts, and chocolate, and oxalates from leafy greens bind the iron and make it unavailable for absorption. Combining whole grains, legumes and leafy greens with vitamin C rich foods (orange juice, green peppers, fruits) increases the bioavailability.

While it is definitely possible to have sufficient iron intake on a vegetarian or vegan diet, it may involve careful dietary planning. Because some women may not do this, those who follow these dietary patterns count as risk groups for iron deficiency or iron deficiency anemia. Going into a pregnancy with a suboptimal iron status or even deficiency is not ideal, but early prenatal visits can detect this and start the pregnant woman on an iron supplement.

Folate

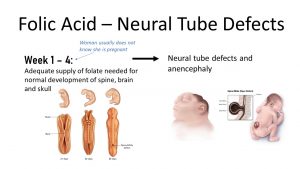

Negative Effects of Folate Deficiency Take Place Before a Woman Knows She is Pregnant

Folate is a different story than iron. The effects of insufficient folate intake take place so early in the pregnancy that the woman may not even know that she is pregnant. This is the reason that folate supplements are recommended for sexually active women and especially for women who are planning on becoming pregnant.

During early fetal development, a neural tube forms that will later become the brain, spinal cord, and spinal column. The complete closure of the neural tube takes place by the fourth week of pregnancy.

Incomplete neural tube closure results in defects such as anencephaly, the absence of a major portion of the brain, and spina bifida, the incomplete closure of the spinal column. These defects vary in level of severity and may lead to disability or even death of the fetus or newborn.

Neural tube defects are among the most common congenital anomalies in the United States and correlate with a low intake of folate. Most women in the US do not receive the recommended daily intake of folate from their diet alone. Folate enrichment and the recommendation of folate supplements before pregnancy was one of the most successful nutrition interventions.

Women Need to Prepare for Pregnancy by Taking a Prenatal Folate Supplement

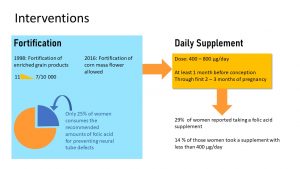

In the 1980s, scientists realized that folate supplementation before conception reduced the risk for neural tube defects in infants. As a consequence, a food fortification program was started in the mid 1990s, in which folate was added to all white flour and various flour products. Neural tube defects decreased from 11 in 10,000 births to 7 cases per 10,000 live births after fortification.

However, studies showed that—even with enriched grain products—many women still did not get enough folate through their diet. The low-carb wave and the recommendation of whole grains (not fortified) instead of white flour products didn’t help.

Today, it is recommended that women start a prenatal folate (400-800 microgram) supplement at least one month before conception, and keep taking the supplement during the first 2 to 3 months of pregnancy.

Problem solved? Unfortunately, no. Only 29% of women getting pregnant took the supplement, and 14% of those women took a regular multivitamin supplement that contained less folate.

Keep in mind that dietary folate or folic acid intake differs by ethnicity. For example, Mexican American women may be at increased risk of deficiency due to decreased consumption of fortified grain products. Traditionally, tortillas from corn masa were more common than bread products from white flour. Since 2016, corn masa is fortified with folate as well.

Vitamin B12 in Women on a Vegan Diet

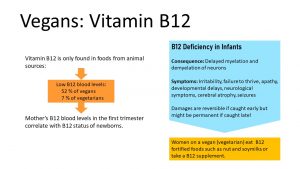

Vitamin B12 is needed in very small amounts, but can only be found in animal products. Analogs in plants do not have vitamin B12 function.

Vitamin B12 is readily stored in the liver and those liver stores can last for years before a person on a vegan diet will start having deficiency symptoms, anemia, and neurological symptoms. Once the deficient person starts taking a vitamin B12 supplement or starts eating animal products, the symptoms are fully reversible.

52% of vegans and 7% of vegetarians have low vitamin B12 blood levels. For the mother this is not a problem, but for the fetus and later infant it is. Studies showed that the mother’s vitamin B12 blood levels in the first trimester of the pregnancy correlate with the infant’s vitamin B12 status.

So why don’t we just give a supplement to the newborn and reverse the deficiency? Deficiency in infants is not always reversible. Sufficient vitamin B12 is necessary for the myelination of neurons, and severe deficiency can even lead to demyelination of neurons. Over time, this can cause permanent nerve damage. Symptoms include irritability, failure to thrive, apathy, developmental delays, neurological symptoms, cerebral atrophy, and seizures. If the deficiency is caught early—before permanent damage is done—the condition is fully reversible. The problem is that vitamin B12 is often the last thing many pediatricians think about when an infant is not thriving.

This is easily preventable. Women on a vegan diet or on a vegetarian diet with only small amounts of egg and dairy should choose vitamin B12 fortified plant milks or take a vitamin B12 supplement. While it is possible to maintain a vegan or vegetarian diet during pregnancy, it involves careful planning on the mother’s part to ensure a smooth pregnancy.

Want to Know More?

Finer LB, Zolna MR. Declines in Unintended Pregnancy in the United States, 2008-2011. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(9):843-852. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa1506575

A measure of income issued every year by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Federal poverty levels are used to determine your eligibility for certain programs and benefits, including savings on Marketplace health insurance, and Medicaid and CHIP coverage. For example in 2020 100% federal poverty level for a family of 4 was $26,200.

Swelling caused by excess fluid in tissue

Gestational Diabetes Mellitus

Feedback/Errata