23 More Critical Periods: Adiposity Rebound And Puberty

Sabine Zempleni and Sydney Christensen

Images copyright 2023 https://www.gettyimages.com/. Included under the provisions of fair use under U.S. copyright law.

After the eventful first year of life, toddlers and preschoolers cruise along growing, developing, and learning. They make enormous developmental strides until they are cognitively, socially, and emotionally ready to go to school. The parent’s job is to provide healthy foods while tolerating temper tantrums, navigating the world of picky eating, providing sufficient exercise and stimulation, and most importantly love their child.

The trips to the physician to track the growth and assess development and health start spacing out to once a year starting with the third birthday. In short, nothing too exciting going on.

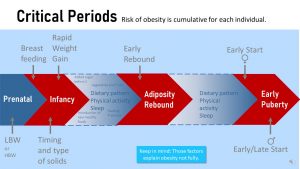

Things start to change as the next sensitive period, which is more a major childhood checkpoint, happens around the ages of 5 to 8. This checkpoint is referred to as the adiposity rebound. Eventually the child will become an adolescent and experience the onset of puberty. Both the adiposity rebound and the timing of puberty onset are reflective of a healthy lifestyle and can act as a predictor of future health.

Before having a closer look at adiposity rebound and puberty lets review the past critical periods:

SGA/LGA Newborns: Infants born preterm or with a low birth weight are at an increased risk for obesity as children and adults. One could ask if this is rather due to the parents lifestyle? Studies show that the risk for obesity is connected to low birthweight and this seems to be independent of parental weight and lifestyle habits. Scientists hypothesize that this is due to the rapid catch up growth that happens in SGA newborns after birth. The molecular mechanisms are not clear, but there is clear evidence that rapid growth during infancy increases the risk for obesity and chronic diseases later in life.

High birthweight or macrosomia, especially if connected with gestational diabetes, is also associated with a higher risk for obesity later in life. The greater association is found with low birth weight infants though.

Breastfeeding promotes ad libitum feeding, a healthy, resilient gut microbiome and a balanced immune system. Breastfed infants tend to have a lower risk for obesity in childhood.

A similar connection is seen for the timing and type of solids. The timing of the introduction of solids can determine the gut microbiome composition, eating behaviors, and taste perception which are important factors in maintaining a healthy lifestyle. There are some studies that show introduction of solids before the fourth month is associated with a higher risk for obesity, however this hypothesis needs more understanding of the underlying physiological mechanisms. Generally, scientists think that all of this is connected to the gradual development of a healthy gut microbiome.

In addition to the timing of solids, the food choice is important as well. The dietary pattern should immediately include ample amounts of vegetables, fruits and whole grains to provide the necessary prebiotics to promote a health gut microbiome. Offering vegetables as a normal part of a meal will also reduce the aversion to the bitter vegetable taste and and avoiding sugary foods until age 2 will help reduce the inborn preference for sweet.

Before you count the healthy or unhealthy decisions your parents made, keep in mind that this is all a mix and match. An infant can start out with a low birth weight but if parents focus on breastfeeding and choose a dietary pattern centered around lots of plant based food, there is a great chance that the child will grow up with a healthy weight.

You Will Learn:

- Development of body composition during childhood and adolescence may determine risk of obesity and chronic disease later in life

- Pediatricians keep using growth charts to determine health status and adequacy of nutrition

- Checkpoint 1: Early adiposity rebound is connected with a higher risk for obesity and some chronic diseases later in life

- Normal timing for the adiposity rebound is between 5 and 8 years of age

- Adiposity rebound before the age of 5 is associated with the risk of obesity and some chronic diseases later in life

- Checkpoint 2: Puberty initiation is influenced by genetics, body fat, and leptin secretion

- Puberty onset: adrenarche and gonadarche are activated

- The adiposity rebound is necessary to trigger puberty

- Leptin is a fundamental modifier for puberty onset

- Timing of puberty onset varies between girls and boys

- Increasing adipose tissue is associated with an earlier puberty onset in girls

- Increasing adipose tissue influences puberty onset, but it is more complicated

- Early puberty onset might make it more difficult to go healthy through life

Development During Critical Periods May Determine the Likelihood of Obesity Later in Life

The two critical periods during childhood and adolescence differ from the critical periods of the infancy and toddler development. In early development, we recommend specific strategies: Gain a healthy amount of weight during pregnancy, breastfeed for 6 months, hold off solids until 6 months, offer a variety of healthy foods to the baby and toddler while allowing them to determine the amount eaten, avoid feeding added sugar until age 2.

After the first two years there are not necessarily specific strategies and recommendations to nudge the metabolism into the right direction. The main focus is now simply on establishing and maintaining a healthy lifestyle.

If the parents teach the child healthy eating, sufficient physical activity, sleep and mental health strategies, and model those choices, the growing child will over time accept them as the normal lifestyle. Vegetable eating and exercising will not be a chore but a normal habit. Establishing these habits can set the person up to reduce the risk of chronic diseases and consequentially increase their likelihood of living a long, healthy life.

We are able to better predict risk of chronic disease and premature death by observing development during critical periods or checkpoints. Long-term studies show a connection between the onset of the adiposity rebound and the onset of puberty. If one or both are early the pediatrician needs to have a conversation with the parents and identify the causes. If the early adiposity rebound is eating related the family should be ideally refered to a dietitian. Dietitians are trained to identify the weak points in a family’s diet and suggest practical solutions that are personalized to the family.

Checking the Onset of the Adiposity Rebound and Onset of Puberty Help to Determine If the Child Is On the Right Track For a Healthy Life

How do parents tell if their child is on the right track to a healthy adult life? Physiologically there are two check points during childhood that allow us as health professionals to make a prediction and intervene if necessary.

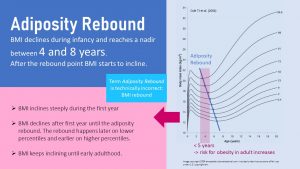

The first check-point is the adiposity rebound. After the first year of becomig a chubby baby the active toddler should be slimming down. Lean mass should increase while baby fat mass declines. This trend of losing fat mass continues until the age of 5 to 8—the timing is different for each child—when fat mass increases again. The point when fat mass increases again is called the adiposity rebound. Note that the term “adiposity” rebound is an unfortunate term chosen by a scientist in the 1980s. For starters “adiposity” has a negative connotation today but the increase in fat mass is physiological. Secondly the term is not precise. The adiposity rebound should rather be called the BMI rebound because the BMI shows this pattern.

The fat mass increase between age 5 and 8 is necessary as a preparation for puberty. The second checkpoint is the age of puberty onset. Early onset of both, adiposity rebound and puberty, is connected to a higher risk for obesity.

Pediatricians Keep Using Growth Charts to Determine Health Status and Adequacy of Nutrition

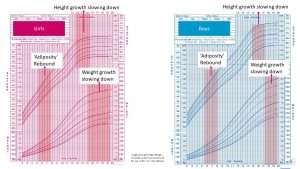

Just like infants, children should grow along their genetically determined growth percentile for height and weight.

Since children tend to grow in spurts and are measured just once a year, they can deviate somewhat from their growth percentile. During one year they might be measureed after a growth spurt and the next before. In the long run children should grow around their percentiles for height and weight.

Notice that the percentiles for weight have a slight bend upwards between 5 to 8 years when children begin to gain some weight back during adiposity rebound. The velocity of weight gain increases well into the growth spurt of puberty. During puberty girls keep adding fat and lean mass. Boys generally increase lean mass during puberty.

While weight increases may fluctuate, height generally develops steadily during childhood.

As we will discuss later in more detail in this chapter, teens experience a growth spurt with the onset of puberty. The growth spurt will slow down when the adolescents are well into puberty. This slow-down varies for each adolescent depending on the timing of the puberty onset, but tends to take place around 12-13 years for girls and 15 years for boys.

Checkpoint 1: Early Adiposity Rebound Is Connected With a Higher Risk For Obesity and Some Chronic Diseases Later in Life

Normal Timing For the Adiposity Rebound is Between 5 and 8 Years of Age

As indicated by the graph, there are pronounced BMI changes—relationship of weight to height—during the first few years of life. This involves acquisition of adipose tissue during the first 6 months of life and more lean muscle mass during the second 6 months of life.

Infants often look chubby even at lower BMI percentiles. Gradually the BMI declines, and the toddler becomes leaner. Toddlers in high BMI percentiles start to appear visually as overweight or obese.

Between the age of 5 and 8 the adiposity rebound sets in, and the BMI begins to increase once again and will generally continue to increase until early adulthood. Adiposity rebound is a normal part of development, and is necessary as a preparation for puberty. Children who go late through the adiposity rebound tend to start puberty later as well.

Children on higher BMI percentiles go through the adiposity rebound earlier while children on low BMI percentiles will go through it later. According to research a late BMI rebound is not necessarily problematic but an extremely early rebound before the age of 5 should ring an alarm bell.

Here is another reason why awareness about the adiposity rebound is important. In our day and age, the adiposity rebound especially in girls is often interpreted as “getting fat” and sending young girls into dieting even though this is a very normal developmental stage. This can lead to a variety of issues later on which we will discuss in subsequent chapters.

Adiposity Rebound Before the Age of 5 Is Associated With the Risk of Obesity and Some Chronic Diseases Later in Life

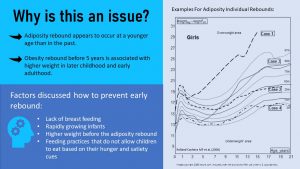

I still remember that the adiposity rebound was clearly visible in my classmates during elementary school. Today, a growing portion of school children are overweight or obese, so the adiposity rebound is often not as noticeable.

When scientists compared the timing of the adiposity rebound from past decades to today it became clear that the adiposity rebound tends to occur today at a younger age in the United States and worldwide than in the past. Other studies showed that an adiposity rebound before age 5 is a red flag and should prompt health care providers to ask questions about the family’s lifestyle. A premature adiposity rebound is associated with a higher weight in later childhood and early adulthood as well as a higher risk for insulin resistance and the risk for metabolic syndrome.

There are a variety of potential factors discussed as contributing to an early adiposity rebound. These factors include lack of breastfeeding, high protein formula, rapidly growing infants, higher weight before the adiposity rebound, and feeding practices that do not allow children to eat based on hunger and satiety cues. High protein intake has also been discussed, but the connection is not as clear.

Overall measuring the adiposity rebound is not an ideal way to design and apply interventions in a clinical setting because it is a retrospective measure. In the daily practice of a pediatrician office it can be helpful though to screen children. Once a pediatrician identifies a child with an early adiposity rebound a careful conversation should be started about the lifestyle of the family. We should always keep in mind that some children may struggle with weight even if their families live a healthy lifestyle.

Checkpoint 2: Puberty Initiation is Influenced by Genetics, Body Fat, and Leptin Secretion

Puberty is initiated by a surge of hormones. This surge marks the end of childhood and the onset of adolescence. The start of puberty typically begins in affluent countries around age 9-10 in girls and 10-12 in boys. This means that the effects these hormones have on developing bodies, brains, and behavior are usually beginning during the preteen years. They are then amplified during the teen years.

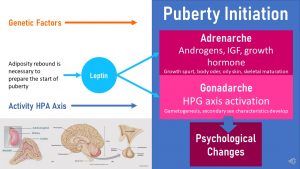

Puberty Onset: Adrenarche and Gonadarche Are Activated

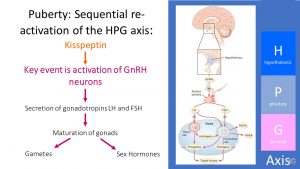

The onset of puberty generally involves the interaction between two physiological processes: Adrenarche, the awakening of the adrenal glands and gonadarche, the awakening of the HPG axis.

During adrenarche, the adrenal cortex on top of the kidneys increases the secretion of steroid hormones such as androgens and cortisol, IGF-1 (insulin-like growth factor), and growth hormone. These hormones contribute to the growth spurt during puberty but also increase body odor, oily skin, and skeletal maturation.

During gonadarche, the HPG axis is re-activated. It is active from the prenatal to early postnatal period, but goes quiet during childhood.

The re-activation of the HPG axis is triggered by a pulsatile secretion of the hormone GnRH. GnRH is produced by specialized neurons in the hypothalamus and released in a pulsatile manner. GnRH is released into the vasculature reaching the pituitary gland stimulating the gonadotropins LH and FSH.

The gonadotropins act on specific cell types in the gonads promoting their maturation and leading ultimately to the production of sex hormones (estrogen, progesterone, testosterone) and maturation of the gametes.

Those pulses also trigger breast development and widening hips in females and growth of testicles and facial hair in males. Both adrenarche and gonadarche play a role in triggering pubic hair development.

The mechanisms that triggers the activation of GnRH neurons to start puberty is not fully understood. The consensus right now is that there is not a specific trigger that starts puberty but a shift in balance between stimulating and inhibiting factors that act on the GnRH neurons. This leads to a change in pulsatile secretion of GnRH.

One of those stimulating factors are the so called kisspeptins. Kisspeptins are neuropeptides produced by the hypothalamus. Their secretion plays a critical role in the function of the HPG axis.

It is thought that this system undergoes substantial developmental changes during puberty maximizing the signaling power on the GnRH neurons until puberty is completed and the teen is sexually mature. It is not quite clear today what exactly controls this timing though.

The Adiposity Rebound is Necessary to Trigger Puberty

One major modifier of the puberty onset is an old acquaintance: Leptin.

When adipose tissue increases during the adiposity rebound more leptin is secreted and leptin blood concentrations rise slightly and adiponectin concentrations decrease slightly. Receptors in the brain register this change and this allows genetically determined factors to trigger adrenarche and gonadarche when the genetically pre-determined time has come.

Keep in mind that leptin and adiponectin changes are not the trigger. Both affect the kisspeptins. Adiponectin inhibits kisspeptin and leptin stimulates it.

Changes in kisspeptin synthesis and secretion stimulate the pulsatile secretion of GnRH. This is just the basic idea. The system is much more complicated though and involves other players as well. Scientists think that for example adipokines and inflammatory cytokines also play a role in modulating kisspeptin secretion. The activity level of the HPA axis also plays a role.

If a child experiences an early or late adiposity rebound, the genetic timing of puberty onset may be modified.

The interplay between the kisspeptins, the HPG axis and the sex hormones eventually matures and results in girls having a monthly menstrual cycle. In boys, hormones are more evenly secreted leading to the production of sperm.

Nutritional Cues Are Fundamental Modifiers for Puberty Onset

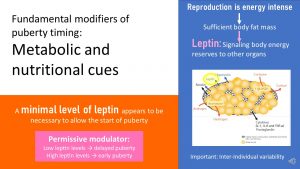

After understanding the general physiology behind the puberty initiation it becomes clear that nutritional and metabolic cues are fundamental modifiers of puberty onset.

Reproduction is an energy intensive process. You already learned how under- and overnutrition impact fertility in both women and men. The same concept applies to puberty. The ability to be fertile and reproduce is closely tied to the amount of energy reserves in the body. Therefore, metabolic imbalances can impact the onset of puberty.

Think back to fertility and the HPG axis. The major player signaling the status of energy reserves and adequate nutrition was leptin. Leptin is a major player during puberty as well.

Leptin is not a trigger for puberty but rather a permissive modulator. More correctly, it seems that a minimum leptin blood level is necessary to allow triggering signals to start puberty. It is thought that leptin acts on the kisspeptin rather than directly on the GnRH neurons.

Details aside, if adipose tissue doesn’t adequately increase during the adiposity rebound puberty is delayed in boys and girls.

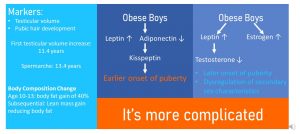

If a child is overweight or obese the onset of puberty tends to be early in girls. For obese boys the connection between adipose tissue and puberty onset is less clear. It is affected differently in boys and girls though.

Timing of Puberty Onset Varies Between Girls and Boys

Increasing Adipose Tissue Is Associated With an Earlier Puberty Onset in Girls

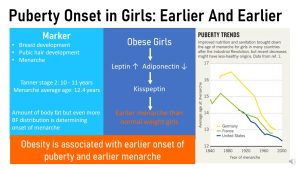

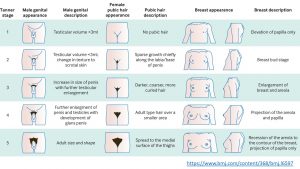

During Tanner stage 1 genitalia grow proportional to the body in boys and girls. No pubic hair or breast growth is visible. The first sign of puberty in girls is a slight elevation of the breast papilla. This is considered Tanner stage 2, onset of puberty. Today, girls in the US go into Tanner stage 2 on average when they are between 9-10 years old. From then on the girl goes step-by-step through the remaining tanner stages. Breasts keep growing and the first pubic hair grows. This would be tanner stage 2. Other changes are the growth of axillary hair, rapid growth, and change in facial structure. Menarche, the first menstruation occurs near the final stages of puberty after 2-3 years of hormonal and physical changes.

Over the last 150 years puberty has started earlier and earlier. If you look at the graph above on the right you see that around 1900 girls started puberty as late as 16 years old. You also see that there are differences between countries. German girls geographically close to French girls started puberty over one year later in average. Along with better nutrition and health care, the onset of puberty kept moving to an earlier age. This trend continued on as girls became heavier all the way to 2000. When data became available for US girls they were more comparable to the French girls and today US girls have an earlier puberty onset than other girls from affluent countries.

Scientists were wondering why there is such a difference in puberty onset. Overall amount of adipose tissue plays a role. Increasing amounts of adipose tissue increase leptin and decrease adiponectin. This changes influences the secretion of kisspeptin which in turn acts on the HPG axis.

The research also showed that the adipose tissue distribution plays a role. If girls carry their adipose tissue more in the gluteofemoral region (around upper legs and butt) they tend to start menarche earlier.

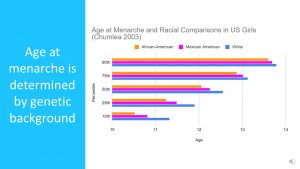

Over the last century the start of puberty kept moving to an earlier age. If we look at US girl you will also see that there are major differences between girls from different ethnicities. The following graph shows age at menarche (not start of puberty).

As indicated by the graph, age at menarche is determined by genetic background. There are clear differences between ethnicities. This study from 2003 shows the variation of menarche between girls (the vertical axis shows percentiles. 10th percentile means early menarche and 90th percentile late menarche). Menarche can start as early as 10.5 years and as late as almost 14 years. White girls in the US have a much later menarche than African American girls while Mexican American girls are in between.

Increasing Adipose Tissue Influences Puberty Onset, But It Is More Complicated

Onset of puberty in boys is a bit more complex. For starters puberty onset—Tanner stage 2—is determined if the testicular size grows over 3 ml. This occurs in average around 11.4 years of age. You can imagine that this is hard to determine outside of a scientific setting. The onset of testicular growth is followed by the development of pubic, axillary and facial hair, rapid growth, and change in facial structure.

The counterpart to menarche is spermarche, the beginning of the production of sperm for boys. Spermarche, also difficult to determine, is often measured by the first occurrence of sperm in the morning urine. The average age of spermarche in the US is 13.4 years.

Overall, this is the reason why we have less substantial data regarding the development of puberty onset in boys over the last decades and ethnic differences.

Obesity in boys and the connection to puberty is also more complicated. Of course, increased adipose tissue leads to increased leptin and decreased adiponectin. This should lead to earlier puberty. But, other mechanisms counter this. Increased leptin tends to decrease testosterone production and obese boys will have higher blood levels of estrogen. This hormonal imbalance moves the puberty onset farther back in age and will also dysregulate the secondary sex characteristics.

Puberty Progression is Measured Using the Tanner Stages:

The progression of puberty in both girls and boys is measured using a system called the Tanner stages. The markers used to determine the stage of puberty for girls are the breast development, pubic hair development and menarche. In boys, the markers are penis and testicle growth and pubic hair development.

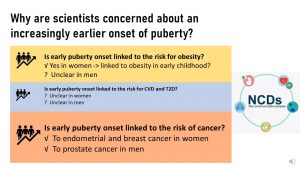

Early Onset of Puberty May be Problematic

Similar to adiposity rebound, an early onset of puberty is connected to an increased risk for health problems later in life.

Connecting early puberty with diseases later in life is difficult. Between the early onset of puberty and the middle age many other factors can influence health. It seems though that the effect of an early puberty is strong enough that the connection can still be detected years later after accounting for other factors.

Research has indicated that early puberty is associated with an increased obesity risk in women, while it remains unclear whether or not men are as affected. It has also been shown that there is an association between early puberty onset and some cancers for both men and women. Cancers discussed are breast and endometrial cancer in women, and prostate cancer in men.

Editor: Gabi Ziegler

NUTR251 Contributors:

- Spring 2020: Ericka Knapp, Justin Porreca, Taylor Donner, Andrea Anderson, Maria Lantos, Tim Gillespie, Colleen Sherman, Rose Davidson, Brett Freitag, Patrick Fisher, Bryce Heiser, Elliot Glaser, Kendyl Heuertz, Eli Havekost, Keeley Hagge, Mariel Sprakel

- Fall 2020: Carly Schwager, Clare Caraghar

Want to Know More?

Gamble J. Puberty: Early starters. Nature. 2017;550(7674):S10-S11. doi:10.1038/550S10a

made in the hypothalamus, is an important hormone that starts the release of several other hormones.

The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis controls reactions to stress and regulates various body processes such as digestion, the immune system, mood and sexuality, and energy usage.

Feedback/Errata