21 Developing Good Taste

Sabine Zempleni

I grew up in the “clean plate” club. My mother put the plate with food in front of me and I had to eat it, vegetables and all. I vividly remember having to stay at the table after dinner to finish my vegetables especially when spinach, broccoli, cabbage, kale, and other cruciferous vegetables were on the menu. Raw vegetables such as lettuce, tomatoes, cucumbers were fine but cooked, bitter vegetables tasted just awful. Today I’m eating and enjoying all vegetables with two exceptions: Creamed spinach and cooked Brussel sprouts.

Is my mother’s strategy the way to go? I never made my daughters eat anything they found repulsive. Both were, like most children less than fond of vegetables. My personal childhood vegetable woes in mind, I encouraged my daughters either to helped me cook or to sit at the kitchen table drawing or completing homework. I used that time to feed them as much of the raw vegetables I was cutting up as they liked. By the time dinner with cooked vegetables rolled around they already ate their vegetable servings. Today, both daughters eat and enjoy vegetables.

Why do so many children, and some adults, hate vegetables? Do we have to accept that vegetables are not for children? Will everybody eat vegetables as an adult anyway?

During this chapter I will explain why children, and some adults, live in a different taste world and how parents can patiently help their children enjoy vegetables over time.

You Will Learn:

Many children in the US eat an unhealthy Western diet right from the start:

- Children in the US do not eat their fruits and vegetables.

- US infants and children eat far too much added sugar.

- Picky eating is a normal development stage for many children

Eating is a complex, multi-sensory experience:

- Taste is a small part of the flavor you perceive when you eat.

- Taste receptors, the olfactory epithelium and the trigeminal nerve deliver the inputs, the brain decides.

- Tactile and auditory inputs add to the eating experience

Children live in a different taste world than adults:

- Newborn infants are primed to prefer sweet and reject all bitter taste.

- Salty taste preference develops in the weeks after birth.

- The infant’s taste preference is not for life.

Parents have a couple of tricks up their sleeve to raise a vegetable lover:

- Dietary learning is more pronounced during early life.

- Mothers eating garlic, carrots and anis forces fetus and infant to get used to the flavor.

- Infants and children need time to accept new foods: Trying 8 – 10 times seems to do the trick.

- Parents need to avoid to ingrain the sweet taste preference: No added sugar until 2 years of age.

- Easier said than done: Parents need to be consistent and patient.

Children In the USA Do Not Eat Their Fruits and Vegetables

Feeding of solid foods starts traditionally with iron-enriched baby cereal mixed with human milk or formula in the USA. Per recommendation the next food following the cereal should be a vegetable and vegetables should be introduced before fruits.

Initially, those foods should be introduced one at a time. After a while around eight months, little meals should mimic the meals of MyPlate. Lots of vegetables, fruits, and whole grains. Strained meats, fish, eggs and dairy should be added. Added sugar should be avoided until age 2 and limited after. Are those recommendations wishful thinking?

If you ask parents about their experience feeding vegetables many share their frustration. Children do not like vegetables at all and getting them to eat veggies is a struggle. This might range from the baby making a face and then clamping the mouth shut to the toddler throwing a tantrum. Most of those reports are anecdotal and might not apply to all families.

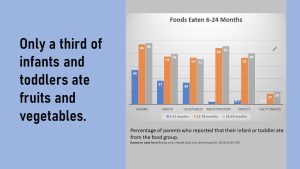

What are US babies and toddlers eating? The 2016 FITS (Feeding Infants and Toddlers Study (FITS) is the largest dietary intake study in infants and toddlers. 10,000 parents participated in a one-time survey describing what their infant or toddler ate at this specific moment in time. Studies like this taking a snapshot cannot tell us how eating develops over time but these types of studies can provide us with an idea what American parents feeding their infants and children.

The reality is bleak. Looking at the graph above, it becomes clear that infants do not eat a variety of foods as recommended and only a third of the babies under 12 months eat fruits and vegetables.

During the second year the eating from all food groups improves. Fruit and vegetable consumption seems to pick up. What is concerning are the bars for sweets. At the end of the second year only 20% of American children do not eat sweets.

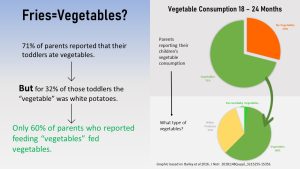

But, isn’t it good news that 3/4 of the children eat vegetables in their second year? The study had a closer look at the little vegetable connoisseurs:

29 % of the toddlers did not eat any vegetables and 71% of parents reported that their toddler ate vegetables. But, when scientists looked at the details 32 % of the “vegetables eating” toddlers ate only white potatoes. No healthy green, orange or yellow vegetables.

29% of toddlers not eating any vegetables at all and another 45 % (32% of 71%) of toddlers eating only white potatoes is pretty atrocious. Maybe things improve as children get older and participates in family meals and healthy meals at day care centers and schools?

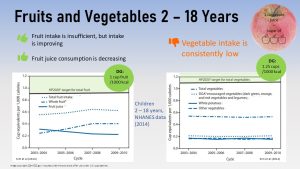

FITS only looked at children under 4 years of age. Here is a set of different data from the CDC looking at changes in fruits and vegetable consumption between 2003 and 2010. During this time extensive parent education about the importance of fruits and vegetables took place. The goal was to increase the average fruit and vegetable consumption so it would reach the black line in the graphs above.

The goal to aim for was set by Healthy People 2020. At the beginning of each decade several government agencies—the lead agency for infants, children and adolescents is the CDC—develop science-based, national objectives to improve the health of all Americans. These objectives trigger educational and policy program. Progress data is collected on the way.

First the bad: American children eat, by far, not enough fruits and vegetables. Vegetable intake is persistently low and did not increase despite parent education. If you look at the graphs above the average intake is so far away from the Healthy People 2020 goal that the entire legend fits into the space.

The good: Fruit intake is improving and—what nutritionist like to see—fruit juice consumption declined nicely. Just as a reminder: Fruit juice tends to have a healthy vibe but this is not true. Health professionals want children to eat their fruit and not drink it. Fruit juice contains a lot of sugar—even if it’s not added sugar—and liquid fruits with the fiber removed does not make children full. Visualize this: One cup of orange juice contains the sugar from 3 oranges. A child would never be able to eat 3 oranges in one sitting but can easily drink the sugar from 3 oranges in one sitting.

More bad news: The Healthy People 2020 goal for fruits and vegetables is not the recommendation, but a realistic target. Even if this first goal is reached US parents need to keep going. The ultimate goal is the recommendation from the Dietary Guidelines (DG) depicted in the green circle and the upper end of the green shaded box.

US Infants and Children Eat Far Too Much Added Sugar

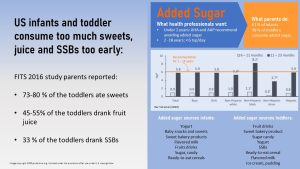

Getting back to the FITS study. The FITS study showed that most children under 2 years of age eat sweets, half of them drink fruits juice, and a third of the toddlers drank SSBs (sugar sweetened beverages).

The recommendation for added sugar intake for children under 2 years is simple: None. This means no candy, sugary milk and yogurt, cookies, cakes, ketchup, baked beans. This also means fruit juice only in small amounts. After the age of 2 the recommendation is less than 6 teaspoons.

Another study gives us additional insights. This study looked specifically at added sugar intake and found that 60 % of the infants and almost all toddlers consume foods with added sugar. The top sugary foods for infants are baby snacks and sweets, bakery products, and flavored milk. For toddlers the top three are fruit drinks, bakery products, and sweets.

Even more scary, these toddlers eat a lot of added sugar. Keep in mind that per recommendation they shouldn’t have any, but in reality toddlers have an average added sugar intake of just under the recommendation for the older children, 6 teaspoons. Black children had the highest added sugar intake and ate the equivalent of 8 teaspoons per day.

High added sugar intake, high consumption of snack food, and low fruit and vegetable intake are in all age groups predictors for overweight and obesity. When it comes to children this is just the tip of the iceberg. During the remaining chapter you will learn that the first years of life are essential for establishing a healthy diet because during this time taste preferences develop.

Picky Eating is a Normal Development Stage For Many Children

My child is a picky eater. My child does not eat vegetables. This is often the argument of parents explaining why their children are on a diet of chicken nuggets, fries, chocolate milk, cereal, pizza, cracker, sweetened yogurt, fruit cups and other unhealthy processed food. Parents tend to be aware that this is not healthy and often follow up with multi-vitamin gums to make up for the missing nutrients.

Picky eating is not well researched and the studies we have are not researching how the eating behavior of picky eaters develops over the course of childhood into adulthood. Are picky eaters replacing healthy fruits and vegetables by overeating snack food and are therefore more prone to obesity or are picky eaters not eating enough and have nutrient deficiencies?

This is complicated by the fact that the term picky eater is scientifically not properly defined. There are several questionnaires exploring the fact if a child is a picky eater or not. This ranges from complicated sub-scales to the one question “Does the child have definitive likes or dislikes for foods?”. Therefore it is not a surprise that the prevalence for picky eating ranges in different studies anywhere between 6 – 50%.

Asking parents only the one question above about 10 – 15% of small children are identified as picky eaters.

The first year of life is a time of learning about different foods, food textures and food preparations. If the baby rejects new foods initially this should not be considered picky eating.

After the first year when the toddler starts making eating decisions, the prevalence for picky eating increases and reaches a peak at 3 years. After that the prevalence declines or plateaus depending on the study.

Overall, the phenomenon of picky eating seems more an issue of developed countries and studies show that it is more prevalent in educated, affluent families with a mother that had a low pregnancy BMI, low parity (the first child; siblings are protective) and is choosy herself when it comes to food.

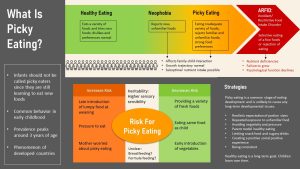

I just keep talking about picky eating, time to define the term. There are a three eating behaviors we need to distinguish.

Neophobia is defined as refusing new, unfamiliar foods.

Picky eating is more complex. Picky eaters are selective eaters with strong preferences or dislikes. In consequence, they have insufficient food variety in their diet. Picky eaters refuse unfamiliar (element of neophobia) and familiar foods. Sometimes they refuse a specific food preparation or how the food is served.

Since every picky eater is different picky eating can affect food groups in varying ways. The studies show though that the vegetable group is most affected sometimes in combination with fruit. Whole grains and meats are the two other food groups that might be affected but to a lesser extend.

The good news for parents is that neophobia and picky eating seems not to delay growth and while nutrient intake is not optimal there doesn’t seem to be a true, damaging deficiency.

These two eating behaviors need to be distinguished from the clinical disorder ARFID (avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder). ARFID is precisely defined in the DSM-5, the diagnostic manual of the American Psychiatric Association. Children with ARFID refuse many and sometimes all food. The consequence are nutrient deficiencies, growth delay and psychological decline. Children with ARFID need medical treatment, often in an in-patient setting.

As I mentioned before picky eating is under-researched, but the evidence points toward several causes that can ingrain the picky eating long-term. Introducing solids late, especially lumpy food deprives the infant of early exposure to a variety of textures and flavors. This makes it harder later on to accept those foods. Children who are pressured to eat are at a higher risk and so are children with a mother that is overly concerned when the child goes through a picky eating phase.

On the flip side early and persistent introduction of vegetables and providing a variety of fresh foods reduces picky eating. Picky eating is less common in families where healthy eating is just a way of life.

Scientists thought that breast feeding might also be beneficial but the results of many studies are inconclusive. Another hypothesis that is confirmed for some children is the heritability of picky eating. Some children inherit a higher sensory sensitivity from parents.

Evidence points toward a combination of learned eating behaviors and heritability when it comes to lifelong picky eaters.

In conclusion, picky eater or not American children do not like or eat vegetables and fruits. As nutrition professionals we can recommend healthy food all we want. If Americans don’t like healthy fruits and vegetables they will not eat it.

Eating Is a Complex Multi-Sensory Experience

The scientific facts are clear. While we can skip meat, eggs and fish, and still have a healthy diet, a diet is not healthy without vegetables. As health professionals and parents alike, our goal should be to find ways to make vegetables palatable to children so vegetable eating will become a lifelong habit.

This task will get easier if we understand how children experience foods.

Taste Is a Small Part of the Flavor You Perceive When You Eat

Taste is a fascinating subject to me. I love to cook and love to experiment with different flavors. I love to go out and eat ethnic food with interesting new flavor profiles. Are you able to define taste, flavor and flavor profile? Many people mix those terms up and for the purpose of this class we need to stick to the scientific definition:

Taste is defined as the sensation we perceive when food comes into contact with taste receptors located in the oral cavity predominantly the tongue. I’m sure you already learned about the five tastes in biology: Sweet, sour, bitter, salty and savory. Each of the those has a set of taste receptors on the tongue (and other places; more later).

From an evolutionary standpoint, taste was the guiding principle when humans still scavenged for food.

- If something tasted sweet it would point to energy-rich carbohydrates and indicated a good food choice. Even better if the food combined sweet and sour because this would point towards energy rich fruits.

- Sour indicated vitamin C in fruits a vitamin that is essential for humans but not for most other animals.

- Mild bitter taste found in vegetables indicates essential nutrients and phytonutrients needed for a healthy metabolism. But, most toxins in plants taste intensely bitter a taste we tend to reject.

- Sodium is rare in foods if you don’t live at the sea. Having a preference for salty taste enabled those food scavengers to eat more if they found it.

- Uncooked meat and beans are hard to digest. Interestingly, meat and other proteins do not taste savory until they are cooked or fermented. Therefore, savory taste guided scavenging humans to easily digestible amino acids.

While scientists understand those five tastes well, there is more and more evidence that there are probably more than five taste receptors. It seems there are also taste receptors for fat, calcium, the carbohydrate maltodextrin and water.

Taste Receptors, the Olfactory Epithelium and the Trigeminal Nerve Deliver the Inputs, the Brain Decides

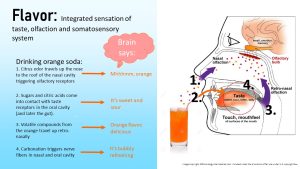

If we could just taste the five tastes, food would be bland and eating not very enjoyable (at least not for me). Tasting is a complex process and there is much more going on than the five taste receptors detecting sweet, sour, bitter, salty, and savory. Let’s assume you take a sip of orange soda.

First the sugar and citric acid come into contact with the taste receptors on the tongue. This triggers a message to the brain. The brain concludes: Sweet and sour.

At the same time the carbonation triggers nerve receptors in the mouth and the nasal cavity, and also sends nerve impulses to the brain: Bubbly and refreshing.

The volatile flavors in the orange soda are set free in the mouth and travel up the back of the throat to the nasal cavity (retro-nasally). The smell of the soda travels up the nose. This triggers olfactory receptors in the roof of the nasal cavity to send a neural message to the brain: Orange flavor.

Ultimately the brain decides what flavor our food has but the inputs comes from three different sources: Taste receptors, olfaction and somatosensory pathway. Together this allows us to detect very complex flavors in our food.

The tongue is laced with five—or potentially more—taste receptors. Sweet, salty, sour, bitter, and savory. Initially, it was thought that different regions of the tongue house a different set of taste receptors but this idea seems to be too strict.

Newer research shows that taste regions overlap and taste receptors can also be found in the cheeks and along the gastro-intestinal system. In those places the taste receptors register less taste sensation but monitor nutrients traveling along the GI system.

The roof of the nasal cavity is lined with thousands of epithelial cells, the olfactory epithelium. These cells register volatile chemicals that are set free during chewing. The olfactory epithelium is connected via nerve fibers to the olfactory bulb sitting below the brain.

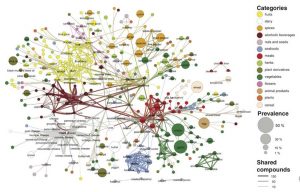

Here is the cool thing: Each of those epithelial cells picks up different flavor substances. Since there are thousands this will allow us to detect an incredible variety of flavors. The illustration above maps the volatile compounds picked up by the olfactory sensory system. Spend a minute or two to explore this map. There are thousands of of volatile compounds. Note that food groups often share similar volatile compounds but food groups can also overlap sharing compounds.

In the nasal cavity the flavor goes from five basic tastes to the complex flavors we experience when eating. Think back when you had a cold and your nasal passages were swollen and clogged. Food tasted bland and flavorless because the olfactory system is not working anymore.

Taste receptors and olfactory epithelium detect flavor but the experience of food is so much more. Soda is bubbly and refreshing. Salsa is spicy, rhubarb is astringent. Eating a jalapeno pepper will burn your mouth, and make your eyes tear up and nose runny. Those taste sensations are picked up by nerve endings in the mouth, nasal passages, but also all over the gastrointestinal system the. This information the somatosensory system picks up is also reported to the brain.

The brain links all this information together and adds more.

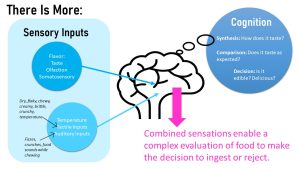

Tactile and Auditory Inputs Add to the Eating Experience

Food has a tactile quality. Food can be liquid, creamy, viscous, soft, hard, stringy, crunchy, crisp, brittle. Food can have a different. These inputs come from teeth and jaws. Eating and chewing also generates sound. Food can sound crunchy, crackly or squeaky.

All together, this will lead to a very complex sensory experience while eating. On top of all those multiple inputs they interact with each other. Salty enhances sweet. Warm changes the intensity of flavor perception. Even a rough spoon might elicit a salty taste.

While all those inputs arrive, the brain synthesizes them comparing them to learned flavor patterns. Bitter taste in a beer is pleasant, but bitter taste in milk tends to point to spoiled milk. That way the brain makes a decision. Edible or not edible? Pleasant texture or overcooked food. Does an apple taste mushy or crunchy, sweet and slightly tart as we like it? Does the food have a good quality? How intense is the taste? Too much or very bland? How does the taste develop during chewing? How long is the potato chips crisp and when do they start getting soggy? Old or fresh potato chip? In what order do flavors appear during the chewing process? Have you ever tried spicy food and the burn of the spice comes only after several seconds? Make sure to pay attention to all those inputs when you eat.

This synthesis, comparison and evaluation of the food takes place in milliseconds and the final action is spitting or chewing and swallowing. We also will make a decision based on the deliciousness of the food how much and fast we eat.

Children And Adults Live in a Different Taste World

When infants are born the decision what is edible, even how much to eat is driven by inborn instincts. Those instincts are set up to drink breast milk. Once the infants starts eating solids at 6 months the adventure of building a food data base in the brain begins. Infants and small children will need to learn what is edible and decide what is delicious, tolerable, or needs to be rejected. They will also need to build memory what different foods are supposed to look, taste and feel like.

This learning process takes place—very much to the frustration of the exasperated parents—in a different taste world.

Newborn Infants Are Primed to Prefer Sweet And Reject All Bitter Taste

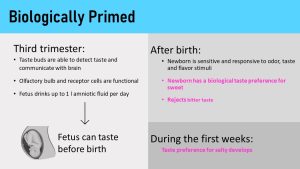

We tend to think of the fetus being busy with growing and maturing. Seldom do we think about the fact that during the last trimester the taste receptors and olfactory bulb become functional.

The fetus drinks up to one liter of amniotic fluid per day during the last trimester. Here is the fascinating part. Some volatile flavors from the mother’s diet make it into the amniotic fluid and the fetus can taste them.

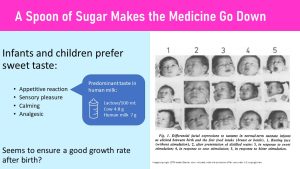

When the infant is born the taste receptors are functional and studies show that the newborn is primed with a strong preference for sweet taste and rejects all bitter tastes. Preference for a weak salty taste develops during the first weeks of life. See the pictures of the newborns below reacting to a drop of a sweet, sour and bitter solution on their tongue. Sweet taste is clearly a sensory pleasure for the newborn.

Linking back to the first idea in this chapter: Taste developed as a guiding principle to make good food choices when scavenging food. What is the purpose for the strong sweet preference?

The key to understanding this is the flavor of breast milk. The cow milk you drink has a lactose content of 4.8 g/100 ml. If you evaluate the sip of milk in your mouth you will come to the conclusion that cow milk tastes faintly sweet.

Human milk has double as much lactose and tastes double as sweet. The preference for sweet ensures that the infant drinks sufficient amounts of milk.

The effect of the sweet taste goes far beyond sensory pleasure and appetitive stimulation. Studies also show that feeding infants something sweet has a calming effect.

This effect was so obvious the mothers in the past that they would dip a pacifier into honey to calm the infant. While this works it should absolutely not be done. Honey can contain the toxin producing bacterium clostridium botulinum and can be very dangerous to the infant in the first year.

These studies also demonstrate that infants experience pain less when they are fed something sweet such as breast milk. Some physicians ask the mother to nurse her infant before giving a vaccine shot or conducting other procedures inflicting pain.

Bitter taste elicits the opposite response. If you look at the newborns’ faces above, you see that placing a bitter test solution on the tongue clearly indicates rejection. Strong bitter flavors warn of poisons. Therefore it is a great defense mechanism for the baby once it becomes mobile and puts all sorts of things in the mouth.

When the baby starts eating solids, the baby is more and more exposed to weak bitter flavors and starts accepting some. Interestingly, even before the introduction of solids the breastfed infant is exposed to bitter tastes. Breastmilk is not just sweet, but can also have a faint bitter note when the mother eats for example plenty of cruciferous vegetables. Combining sweet and bitter will mask the bitter taste.

As the child grows into an adult the threshold for bitter, which is very low for a young child, increases due to the exposure to vegetables. The older child is less able to detect bitter flavors in the food.

For those reasons many babies and toddlers will accept vegetables after a few attempts with exception of the so called PROP super tasters.

Bitter taste is more complex than sweet taste. We humans have 25 bitter receptors in our mouth picking up different variations of bitter taste. One of the receptors detects a type of bitter taste called PROP (6-n-propylthiouracil) which can be found in cruciferous plants such as broccoli, turnip, Brussel sprouts and cabbage. The gene coding for this receptor has different variations in humans. Which genetic variation of the gene is inherited determines if the child has a low, intermediate or high taste threshold for this bitter taste.

People with a low taste threshold are called PROP super tasters. PROP super tasters experience the bitter taste in cruciferous vegetables much more intensely and are of course not very fond of vegetables.

Salty Taste Preference Develops in the Weeks After Birth

Preference for salty food is not present at birth but develops over the first weeks of life. Humans are omnivores, eating a mix of plants and meats. Since meat contains more sodium than plant foods humans prefer a weak salty taste. Herbivores have very little natural salt sources in their diet and prefer strong salty tastes. Cows and deer for example love to lick salt.

Here is another interesting bit of scientific information about taste preferences. Sweet and salty preferences are connected and this makes food that combines both tastes so appealing. The preference for salt is even stronger when children and teens are in a growth spurt.

The Infant’s Taste Preference Is Not For Life

While infants are born with specific taste preferences this pattern will not remain lifelong. The preference for sweet will decline during adolescence and bitter taste will become less pronounced.

If we compare the bliss point for sweet it becomes even clearer that children and adults live in a different taste world. When adults test liquids with different degrees of sweetness they prefer a liquid with around 7 teaspoons of sugar per cup. This is very close to the sweet taste of sodas. I’m sure this is not an accident.

When the same test is run in infants or children they opt for liquids with 12 teaspoons per cup of liquid. I’m sure it is also not accidental that products designed for children are much sweeter than the adult products.

Parents Have a Couple of Tricks Up Their Sleeve to Raise a Vegetable Lover

Dietary Learning Is More Pronounced During Early Life

Understanding how taste is primed at birth and develops through childhood allows us to understand why vegetables are not a favorite foods for many children. Flavor preferences are a gate keeper for infants: Preference for sweet stimulates infants to drink breast milk. Rejection to bitter protects the infant from ingesting poisonous food.

Should parents hold off offering vegetables until the bitter taste perception is less pronounced and the child will accept vegetables more readily? Is vegetable feeding torture for young children (it sure is for many parents)? At the beginning of this chapter you saw that American parents seem to do just that. Children have very little vegetables in their diet, but ample amounts of sugary foods.

As you will see during this section this is an extremely bad idea. If parents are not cautious what foods they offer, our current food environment with an abundance of salty and sweet foods can reinforce this early preference and set the child up for a lifelong unhealthy diet.

Helping their offspring to accept vegetables as a tasty food, will require a lot of patience from parents and child. The good news is that with consistency it will get easier over time and there a few strategies that might help.

To raise a vegetable lover parents need to eat themselves a healthy diet that includes vegetables in ample amounts. This will ensure that amniotic fluid and breast milk are faintly vegetable flavored. Next step is the early and patient introduction of vegetables and the avoidance of foods with added sugar until the child is two years old. The remaining childhood parents need to model healthy eating as a normal way of life.

Eating Garlic, Carrots and Anis Forces the Fetus and Infant to Get Used to a Healthy Flavor

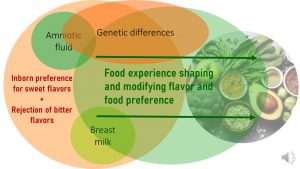

While the infant is primed with a preference for sweet foods and the rejection of bitter foods, the diet of the mother during pregnancy can change the flavor of the amniotic fluid. If the mother eats lots of vegetables and spices the fetus already starts getting used to some of those flavors. The same goes for breastmilk which is also flavored by the mother’s diet. While there are genetic differences how intensely bitter is perceived, the overall food experience will over time modify flavor and food experience.

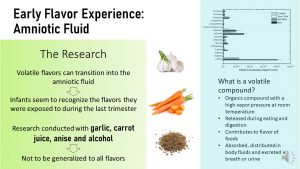

During the third trimester the fetus drinks up to one liter of amniotic fluid. I never thought about what amniotic fluid would taste like, but it has been shown that food flavors are transferred into the amniotic fluid.

Volatile compounds, for example from alcohol, anise, carrot or garlic, seem to be transferred into the amniotic fluid. If the infant is later exposed to those flavors again acceptance is better. It is unknown at this point though if this is true for all foods or just a select few. We cannot draw the conclusion that the infant is automatically willing to eat a diet similar to the maternal diet.

When I was in elementary school my family went on hiking vacation in the Alps and stayed on a farm high up the mountain. Part of the breakfast served every morning was fresh cow milk directly from the stable, cow-warm. I still remember vividly that this milk was the grossest food I ever consumed. It tasted intensely like silage and all sorts of other flavors. My parents on the other hand thought that this was a healthy treat and I spent the vacation starting every morning being grossed out.

Clearly, milk tastes differently depending what the cow is fed. Those Alpine cows ate only fresh grass and the chemical resulting from the rumination of the grass gave the milk the silage, stable taste. In contrast the milk we buy in the store has a much more neutral taste.

Dietary volatiles—other volatiles such as tobacco as well—are diffusing from the blood stream into the milk. Research shows that concentrations of those compounds are at a level where they can be smelled or tasted.

The scientific hypothesis goes that the food a woman eats during lactation flavors the breast milk. Scientists hypothesize further that with eating a variety of foods the subtle flavor of her the mother’s milk changes from day to day as well.

In consequence, breastfed infants are already exposed to a variety of subtle flavors before they even start eating solids. This all makes sense because the food the mother eats is what she will feed the infant later. For example, Asian Indian food is vegetable based and heavily spiced. This will probably influence the breast milk flavor. A woman in the US eating mostly processed food with little spices and vegetables will transmit a different flavor into the milk. Is breast milk then a way to get the infant used to the family food?

A recent review of all studies conducted for this hypothesis found:

- Flavor volatiles are in fact transferred into the breast milk and flavor the milk.

- This happens in a time-dependent manner. Flavor was noticeable after 30 minutes to 1 hour for alcohol and 2 -3 hours for some food flavors.

- Flavors tested were garlic, carrot, caraway, anis, and mint. Interestingly some flavors seemed not be transferred. An example would be fish oil.

- The flavor tended to dissipate during the next 3 to 8 hours depending on the flavor tested.

- Other studies tested the response infants had to those flavors later when solids were introduced. The response was more positive when infants were exposed to the flavor during lactation. This was still shown several months after the exposure from breast milk.

Formula on the other hand has the same flavor every time and therefore the infant is much less exposed to a variety of flavors during the first months.

We need to be cautious though. At this point there is no research available demonstrating that children are later more accepting of a healthy, plant-based diet if the mother consumed that diet during lactation. We know that at this point that there is transfer of volatile substances and some of those are recognized by the infant. Future research needs to show if there is a long-term effect.

Infants and Children Need Time to Accept New Foods: Trying 8 – 10 Times Seems to Do the Trick

Once the baby starts eating solids it is important to introduce a variety of healthy foods, especially vegetables one at a time. Parents should not get detracted by a disgusted face when the baby first tries vegetables. Research shows that it will take 8 to 10 consecutive exposures to increase the amount a baby will eat. Showing the food is not enough, but the vegetable can for example be combined with other foods, such as fruits, the baby or child accepts better.

All in all the parents should not expect wonders. It will take patience and time to increase the acceptance for vegetables.

Parents Need to Avoid Ingraining the Sweet Taste Preference: No Added Sugar Until 2 Years Of Age

The reality is that American children are fed sugary foods very early on and are fed a lot of added sugar.

The reality is that American children are fed sugary foods very early on and are fed a lot of added sugar.

This eating behavior is contrary to the recommendation not to feed any sweets and products with added sugar before age 2. This recommendation has a reason.

You learned that babies are born with a strong preference for sweet taste. Initially, this is a good mechanism to promote sufficient intake of the sweet human milk. In times past when food was not abundant this was also a good strategy to identify energy rich foods.

Today, this sweet preference sets children up for an unhealthy, energy dense diet. Sweets are abundantly available and most processed food is salty, savory and sweet. The sweet preference increases consumption. Research showed that early exposure to added sugar can strengthen this sweet preference and this might makes it even harder to get the child to eat the healthy, bitter vegetables.

Easier Said Than Done: Parents Need to Be Consistent And Patient

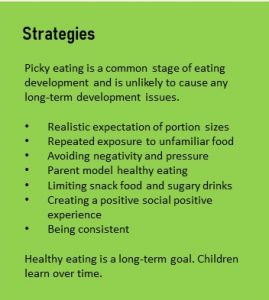

This brings me back to the picky eating section. I jumped over the evidence backed strategies reducing picky eating. Those strategies should be used for all you children, picky or not.

Parent need to keep in mind first and foremost that healthy eating is a long-term goal that requires lots of patience. Negativity and pressure are rather counterproductive. As the studies regarding picky eating show it will not impact growth or development if a child has a picky eating phase.

The (hopefully) relaxed parents should create a positive, social eating environment and modeling healthy eating. The child should be exposed to many different vegetables in realistic portions. When parents eat vegetables every day consistent, repeated exposure in small amounts is easier.

In addition foods with added sugar should be avoided until age 2 (this will be a difficult conversation with grandparents, aunts, uncles and often the daycare provider) and then limited along with snack food. That ensures that the child is actually hungry for meals and planned snacks.

It will still be rather a marathon than a sprint.

Editors: Eric Hanzel, Gabi Ziegler

NUTR251 Contributors:

- Spring 2020: Rawan Al Jabri, Jordan Juracek, Alex Casebeer, Eugene Baraka, Tina Dinh, Audrey Freyhof, Miranda Haverdink, Brittany Southall, Caleb Licking, Eli Havekost, Caroline Leibel, Keeley Hagge, Danae McKenzie, Jenny Holguin, Hailie Slepicka, Grace Neville, Tim Gillespie, Julia Curtis, Madison Yourstone, Jenna Junker, Kealy Barnes, Dylan Fruhling, Dylan Ernesti, Kennedie Engles, Ericka Knapp, Patrick Fisher, Bryce Heiser, Krissy Krager, Alondra Iturbide, Mariel Sprakel

Want to Know More?

Healthy Children (American Academy of Pediatrics): Nutrition

Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Nutrition For Kids

Feedback/Errata