13 Pre-Pregnancy Weight And Healthy Weight Gain During Pregnancy Are Predictors of a Healthy Pregnancy

Sabine Zempleni

Nutrition professionals recommend that pregnant women eat a plant-heavy, nutrient dense diet with added dairy, small portions of fatty fish, eggs, and lean meat. In short, nothing special. The question is now how much food? What type of foods? What about cravings and can a pregnant woman give in to those cravings? How does a pregnant woman know if her energy and nutrient intake is sufficient?

You Will Learn:

- Adequacy of nutrition during pregnancy is determined by maintaining a recommended weekly weight gain (GWG).

- Recommended weight increase depends on the pre-pregnancy BMI:

- 1lb/week for BMI under 25

- 0.6lb/week for overweight women

- 0.5lb/week for obese women

- Recommended weight increase depends on the pre-pregnancy BMI:

- Today, more women enter pregnancy overweight or obese increasing the risk for pregnancy complications. Only 1/3 of pregnant women achieves recommended weight gain.

- The main pregnancy complications—GDM, hypertension, pre-eclampsia—are connected to the combination of pre-pregnancy weight and weight gain during pregnancy.

- Maternal obesity is linked to an increased risk for adverse outcomes to the fetus, birth, and child development.

- Being underweight before pregnancy combined with insufficient weight gain during pregnancy increase the risk for adverse outcomes to the fetus.

- Free prenatal care should be offered to all pregnant women. Care should include individualized attention.

Recommendations for Weight Gain in Pregnancy Vary Depending on the Pre-Pregnancy BMI

The first step at every prenatal check-up is a trip to the scale. Weight increase throughout the pregnancy is closely monitored and compared to the recommendations.

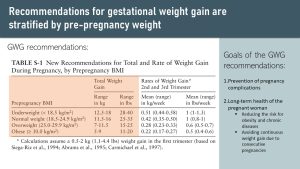

The following table depicts current recommendations for weight gain during pregnancy. There are two important takeaways from the data:

- Noticeable weight gain is not expected until the second trimester. Only a small amount, around 0.4 pounds per week, is expected during the first trimester in women with a low or normal BMI for adipose tissue growth. This small weight gain stems from the slight increase of adipose tissue so the woman has sufficient energy reserve for the pregnancy and breast feeding.

- Expected weight gain depends on the pre-pregnancy BMI.

The current gestational weight gain (or GWG) recommendations are relatively new. At the beginning of the 21st century, the rising prevalence of obesity resulted in increasing numbers of women entering the pregnancy overweight and obese. Scientists suspected that the one-size-fits-all approach of gestational weight gain recommendations didn’t work anymore.

Studies researching both pre-pregnancy BMI and GWG in association with pregnancy outcome confirmed this:

- Excessive weight gain during pregnancy is a risk factore for pregnancy complications.

- Excessive weight increase during the first trimester is a stronger predictor than weight increase during the second and third trimester.

- The pre-pregnancy BMI is a stronger predictor for negative pregnancy outcomes than the gestational weight gain.

When the GWG recommendations were developed, scientists also considered if weight loss during pregnancy would help obese mothers reduce their risk for LGA newborns, macrosomia, and cesarean delivery. The first issue is that⏤although risk for LGA newborns was reduced⏤the risk of giving birth to SGA infants increased. In addition, the risk for pregnancy complications was not reduced. In addition, high blood concentrations of ketones, potentially occurring during weight loss, seem to have a negative impact on neurological development of the fetus. The conclusion was that weight loss during pregnancy is not recommended.

Based on this research, the new GWG recommendations were designed, stratisfied by pre-pregnancy BMI. According to the recommendation a pregnant woman should gain around one pound per week starting in the second trimester if her pre-pregnancy weight is in the underweight or normal weight BMI category. Overweight women should gain 0.6 pounds per week, obese women 0.5 pound per week.

The primary goal of these recommendations is the reduction of pregnancy complications. Women who gain more weight than the GWG recommendations have a higher risk for pregnancy complications such as gestational diabetes, hypertension, and preeclampsia. Risk for macrosomia and birth complications also increases. On the other hand, if the weight gain is below the recommendation, the newborn tends to grow slowly, called SGA, and has a risk of a premature birth.

For women carrying twins, different recommendations apply. The current recommendations according to BMI are the following:

- Underweight: 50 – 62 pounds

- Normal weight: 37-54 pounds

- Overweight: 31-50 pounds

- Obese: 25-42 pounds

To fully understand the GWG recommendations, understanding the composition of pregnancy weight gain is important.

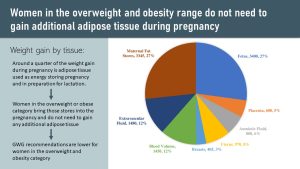

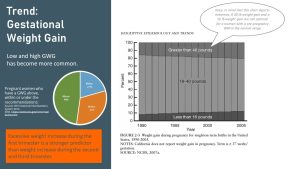

The pie chart shows that at the end of the pregnancy, 50% of the weight gain stems from the feto-placental unit (fetus, placenta, amniotic fluid, uterus). Another 25% is associated with blood volume, extracellular fluid, and breast tissue.

The remaining weight gain, roughly another 25%, stems from maternal fat stores. This additional energy store for pregnancy and breastfeeding is not needed if women bring large adipose tissue stores into the pregnancy. On the opposite spectrum, underweight women should gain more adipose tissue to build up these energy stores.

This is why recommended weight gain is lower for overweight and obese women and higher for underweight women; it depends on existing adipose tissue stores.

The second reason, often neglected, why excess maternal weight gain should be avoided is that excessive pregnancy weight gain is a predictor for obesity and chronic diseases in those women after the pregnancy.

Excessive weight gain during pregancy will make it more difficult to get back to the pre-pregnancy weight after birth. Consider a woman going through several consecutive pregnancies and retaining additional weight after each pregnancy. She will not only become obese, but go into each successive pregnancy with a higher BMI. This will increase the risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes for these consecutive pregnancies.

Why Are We Using Pre-Pregnancy BMI, But Weight Gain in Pounds For GWG?

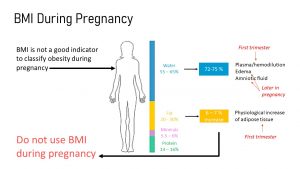

One of the most common tools to measure obesity is the Body Mass Index or BMI.

The BMI works reasonably well for majority of American adults as a rough scanning tool to determine if a health care provider needs to follow up with other health assessments. If we interpret the BMI correctly, we need to be aware of the population groups that BMI measurements do not work for though. This includes adults who have a high lean body mass or are very tall or very short as well as children and very old adults.

Here is another group the BMI does not work for: Pregnant women. While the physician will use the BMI to scan to determin if a woman might be in a risk group at the beginning of the pregnancy, the BMI is off the table during pregnancy. Here is why:

During pregnancy, the body composition changes. This includes an increase of body water from about 50-60% to 72-74%, as well as a fat mass increase of about 6-7%. Mineral and protein content go up as well. All of these factors contribute to a physiological increase in weight, and thus a difference in calculated BMI.

The main predictor for a healthy uneventful pregnancy is the combination of pre-pregnancy BMI and weight gain during pregnancy. Studies show that both parameters are correlated to the likelihood of pregnancy complications.

More Pregnant Women Enter Pregnancy Overweight and Do Not Adhere to the GWG Recommendations

Studies investigating the connection between pre-pregnancy BMI, pregnancy weight gain, and pregnancy outcome demonstrate clearly that:

- Women entering pregnancy with a BMI in the normal range have the lowest risk for pregnancy complication.

- Women who gain the recommended amount of weight for their pre-pregnancy weight have the lowest risks of pregnancy complications in their BMI group.

Today, More Women Enter Pregnancy Overweight or Obese

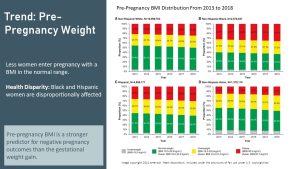

As mentioned before, due to the increasing prevalence of obesity over the last two decades, more women enter pregnancy obese.

Today, almost 32% of women in the reproductive age range are obese, and 7% are further categorized as having class III obesity. When combined with overweight women, this prevalence is almost 56%. The prevalence in African American and Hispanic women is even more worrisome. 56% of African American women in the reproductive age range are obese, with 74% overall being obese or overweight.

Pregnant Women Often Do Not Meet the GWG Recommendations

Here is another concerning reality. Statistics show that only a third of pregnant women manage to stay within the GWG recommendations; in fact, almost half of pregnant American women gain weight above the GWG recommendations.

When we look closer at the trends in GWG over the last decades, something else becomes clear. Extreme weight gains, either above or below the recommendation range, have become increasingly common. Notice the darker shaded areas in the graph above. Not only are a good portion of women gain too much weight during pregnancy but that the number of women who do not gain sufficient amounts of weight during pregnancy is increasing as well.

The Main Pregnancy Complications—GDM, Hypertension, Preeclampsia—Are Connected to High Pre-Pregnancy BMI And Excessive Weight Gain During Pregnancy

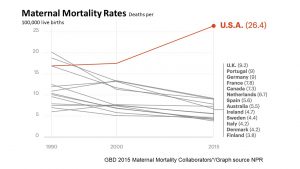

During the last century, maternal mortality has decreased substantially in high income countries, largely due to advances in medical care such as blood transfusions, antisepsis, improved operative and anesthesia techniques, and antibiotic use.

While other affluent countries kept lowering their maternal mortality rates, the US rates are disturbing and increasing steeply.

The US has—by far—the highest maternal mortality rate of all developed nations with 26 out of 10,000 pregnancies. The next highest is the United Kingdom, with slightly over 9 out of 10,000 pregnancies.

Causes are not fully clear, but increasing maternal age combined with the high prevalence of overweight and obese pregnant women and lack of prenatal health care for low-income women are discussed.

The high mortality rate is not equally distributed in the US population. Black women are much more affected than Caucasian women.

While many obese women have normal pregnancies and healthy babies, from a public health standpoint, the increased risk for maternal death makes it important to learn about risk obesity poses for pregnant women.

Gestational Diabetes (GDM)

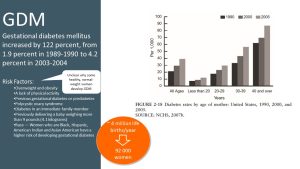

According to the CDC, 2-10% of pregnancies in the US are affected by gestational diabetes every year, and 50% of women who develop GDM go on to develop T2D. Even more concerning is that we saw a doubling in GDM from 1990 when the prevalence was just 2% to 4 % in 2004.

2 or 4 % of pregnancies may not sound like that much of a difference, but if you multiply this percentage with roughly 4 million life births that take place every year in the US, you will have 92,000 women developing GDM each year!

Before you learn about the connection between obesity and GDM, it is important to keep in mind that GDM is not solely an obesity related pregnancy complication. Genetic predisposition for insulin resistance can result in GDM during the last trimester of the pregnancy in otherwise healthy, lean women. Obesity aggravates a genetic predisposition.

Here is the problem. Many obese women already bring insulin resistance into the pregnancy, even if they have not been diagnosed with prediabetes or T2D.

The following infographic depicts how pathological insulin resistance aggravates physiological insulin resistance (which you are already familiar with) during pregnancy:

Starting during the second trimester, muscle and adipose tissue are becoming progressively less insulin sensitive. Blood glucose concentrations after a meal stay elevated longer and insulin secretion increases to compensate for the elevated blood glucose levels.

This is not a health issue for women with a healthy glucose metabolism before pregnancy. After pregnancy their insulin sensitivity and insulin secretion will go back to normal.

If women go into a pregnancy with already existing insulin resistance or prediabetes and add to that the physiological adpations during pregnancy GDM will develop. The pancreas will need to work overtime to secrete enough insulin to clear blood glucose after a meal.

GDM or excessive insulin resistance tend not to have clearly noticeable symptoms. Therefore, a routine glucose tolerance test between week 24 and 28 evaluates how fast glucose is cleared after a meal. The pregnant woman drinks 8 ounces of sugar solution, and blood glucose is measured after 1 hour. If the blood glucose concentrations are 180 mg/dl or higher, blood is taken at the 2 and 3 hour mark. A diagnosis of GDM is made when 2 or more of the blood glucose levels meet or exceed a threshold.

GDM is associated with increased blood glucose concentrations, delayed clearance after a meal, and the release of more free fatty acids from the adipose tissue. The consequences are similar to T2D. An overworked pancreas and glucolipotoxicity can damage the beta cells of the already strained pancreas. Once the pancreas is not able to compensate for the insulin resistance by increasing insulin secretion, blood glucose levels will be elevated for much longer after a meal and the mother will consequently be diagnosed with gestational diabetes.

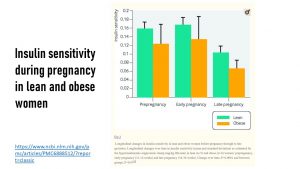

Here is an interesting study that demonstrated the additive effects of reduced insulin sensitivity before pregnancy due to obesity and physiological insulin sensitivity during pregnancy:

Obese and lean women enter the pregnancy with different levels of insulin sensitivity. This difference remains stable throughout the first trimester. Insulin sensitivity declines for both lean and obese women during second and third trimester, but the decline is much more pronounced for obese women and can reach the point when the woman develops GDM.

Normal weight women return to a normal metabolism within a couple of weeks after birth or after breastfeeding. In obese women, the damage to the pancreas might be enough to lead to a T2D diagnosis after pregnancy. Thus, GDM is also a risk factor for developing T2D later in life.

There are some ways to reduce the risk of experiencing gestational diabetes; some studies support increasing physical activity and consuming a Mediterranean or DASH-based diet.

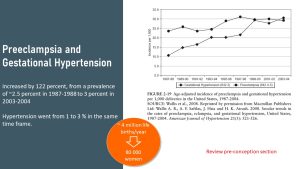

Preeclampsia And Hypertension

One of the worst case scenarios in pregnancy is preeclampsia, a truly scary condition that can lead to premature birth, stroke, and potential death of the mother and fetus. Maternal age, obesity, and the lack of prenatal care contribute to the risk of developing preeclampsia.

Again, 3% of pregnancy might not sound like a lot, but from a public health standpoint this translates into 80,000 women affected by preeclampsia each year.

Recall from the pregnancy preparation chapter that preeclampsia has a variety of symptoms that tend to show up during the last half of the pregnancy. What makes this disease even more worrisome is that it can happen after a seemingly normal birth. It becomes especially dangerous because many women⏤and even health care providers⏤dismiss one of the more common symptoms, the sudden severe headaches.

If preeclampsia develops during the pregnancy, the best outcome is a prematurely born baby since delivery is the only way to treat and reverse preeclampsia. Depending how early the baby is born, it will face many obstacles during the first months of life and run the risk of permanent disability.

The best way to prevent preeclampsia is to start the pregnancy as metabolically healthy as possible. During the pregnancy blood pressure and protein content in the urine should be consistently monitored at regular prenatal visits, since those are the first two symptoms of a developing preeclampsia.

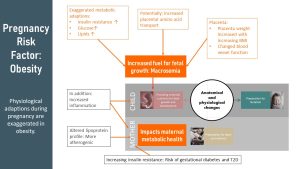

Maternal Obesity Is Linked to Fetal Risks

Obesity during pregnancy increases the risk for both the mother and fetus during pregnancy and birth. Preterm birth, very small, or large birthweight can even affect metabolic health throughout the lifetime of a child.

The risks to fetal health also stem from the obesity-induced exaggeration of the normal physiological adaptations during pregnancy.

During Pregnancy

- Insulin is growth-stimulating and increases circulating amino acids in the blood—obese women might come into pregnancy with various degrees of decreased insulin sensitivity and higher insulin blood concentrations.

- Elevated insulin blood levels and the oversupply of nutrients trigger the placenta to grow larger than normal and to develop an extensive blood vessel system. Placenta weight is correlated to BMI; the higher the BMI, the higher the placental weight.

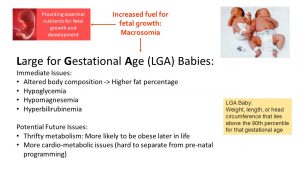

Those exaggerated adaptations—including larger placenta and more nutrients—lead to faster fetal growth. The result is macrosomia. Macrosomia describes newborns weighing more than 4,000–4,500 grams (8 lb. 13 oz) at birth.

Perinatal Complication and Future Health of Macrosomic Infants

You might think, why does it matter if a baby is larger at birth? Large babies can get injured during their passage through the birth canal. If the infant is too large to be born naturally, a C-section will be necessary. C-sections are risky for obese mothers for a variety of reasons. Anesthesia has increased risks in obese women, and epidurals are sometimes hard to place. Slow wound healing or infection of the incision are also risks for obese women.

Aside from the maternal risks, the large newborn needs emergency attention after birth. The baby will be born with low blood glucose levels and will have trouble regulating the glucose blood concentrations. Hypomagnesemia is also likely and needs to be treated. Hyperbilirubinemia, commonly known as jaundice, is common in many newborns, but very common in LGA babies. Severe cases are treated with UV light.

Large for gestational age (LGA) babies seem to have more cardio-metabolic issues later in life, and are at an increased risk of developing obesity. It is hard to determine if this is due to epigenetic programming because parents were obese, metabolically unfavorable conditions during pregnancy (which can also cause epigenetic changes), or the lifestyle after birth. Studies show that part of the problem can be explained by a thrifty metabolism.

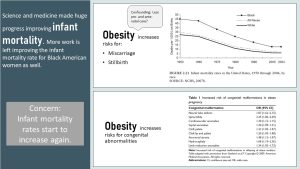

Infant Mortality

While the maternal mortality in the US is trending upward, we made incredible strides lowering the infant mortality rate. Thanks to technology, some premature babies are now able to survive after being born as early as 22 weeks. (Interested? See the Nature article).

Despite all those improvements, obesity increases the risk for miscarriage, premature birth or still birth. There are two reasons. The placenta is not functioning optimally (see prepregnancy and weight chapter) or due to the increased prevalence of maternal pregnancy complications. While technology is advanced, the risk for permanent medical issues is still high the earlier the baby is born.

Additionally, obesity before and during pregnancy increases the risk for an array of congenital abnormalities.

Underweight Pregnancies Bring Increased Risk

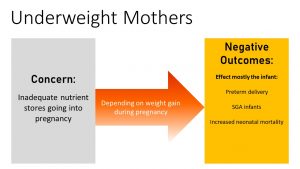

While obesity increases risks for mother and fetus, going underweight into pregnancy will mostly affect the fetus.

Here is the good news. Underweight women at conception who gain sufficient weight during the pregnancy will most likely give birth to a healthy baby.

However, if the underweight pregnant woman does not gain sufficient weight, the infant has the increased risk of preterm deliveries, SGA, and neonatal mortality. Studies following SGA babies show that many develop a thrifty metabolism and are more likely to be obese later in life.

Teen Pregnancy

One group at risk for going into a pregnancy underweight is adolescents.

The United States takes the trophy again for having the highest prevalence for teen pregnancies (59 for every 1000 women) out of 21 different industrialized countries according to a study conducted in 2015.

Digging further into the research, disparities can be found among Hispanic and Black populations , accounting together for over half of the teen pregnancies in 2017. However, there has been a decline in recent years associated with teens practicing safer sex or using birth control.

For those that end up becoming pregnant, there is an added concern to being underweight: adolescent girls can still be in a rapid growth phase, and will end up needing energy and nutrients for their metabolism, growth, and pregnancy.

American teenage women tend to have lower nutrient stores and intake across the board, with nutrient deficiencies seen in folate, iron, and calcium. Insufficient energy intake during pregnancy⏤leading to low weight gain—will prevent the placenta and fetus from growing sufficiently. The consequence is a newborn that is small for gestational age.

The most complications (especially SGA babies) are seen amongst the 12-15 year old pregnancies where the adolescent is still rapidly growing and further has to compete for nutrient intake.

The teen’s pregnancy occurrence or success may be linked to her prenatal weight, socioeconomic status, education level, and access to prenatal care. Regardless of the situation, it is important to ensure that the mother can maintain a healthy weight while increasing her nutrient intake substantially to provide for the growing fetus.

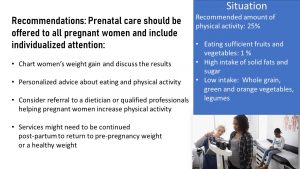

Personalized Nutrition Care Should be Provided During the Pregnancy and After Birth

The best strategy to reduce the risk for pregnancy complications is a healthy, plant-based, mixed eating pattern combined with sufficient physical activity and moderate exercise. In reality, only 1% of pregnant women eat the recommended amount of fruits and vegetables. Whole grain and legume intake is also lacking. Instead, women have a high intake of solid fats and sugar, and only 25% of pregnant women have sufficient exercise.

Obstetricians are typically not educated to address weight or a healthy lifestyle. For a woman to reduce the risk of weight complications during pregnancy, it would be ideal if prenatal care is offered to all pregnant women and that this care would include personal nutrition counseling and exercise recommendations.

Important concepts to discuss with the woman would be an optimal GWG throughout pregnancy and how to achieve it. This would include personalized nutrition, physical activity counseling, and post-pregnancy plan to return to normal weight appropriately.

Interested in More Information?

https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/pregnancy-weight-gain.htmDance A. Survival of the littlest: the long-term impacts of being born extremely early. Nature. 2020;582(7810):20-23. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-01517-z

Editors: Meryn Potts, Sydney Christenson, Eric Hanzel, Gabi Ziegler

NUTR251 Contributors:

- Spring 2020: Julia Curtis, Colleen Sherman, Kendyl Heuertz, Gage Gauchat, Miranda Haverdink, Amelia Johnson, Maddie Korthas, Krissy Krager

- Fall 2020: Morgan McCain, Pierce Krouse, Miles Judson, Peyton Hainline, Megan Appelt

Large for gestational age

Arranged in layers or groups

Small for gestational age

BMI > 40

the process of preventing the growth of infectious germs, like bacteria, viruses and fungi

Low blood magnesium concentrations

Energy efficient metabolism that requires fewer calories for daily activities

Feedback/Errata