31 Ageism Impacts Health and Longevity

Sabine Zempleni

“Joanne Whitney, 84, a retired associate clinical professor of pharmacy at the University of California-San Francisco, often feels devalued when interacting with health care providers.

There was the time several years ago when she told an emergency room doctor that the antibiotic he wanted to prescribe wouldn’t counteract the kind of urinary tract infection she had.

He wouldn’t listen, even when she mentioned her professional credentials. She asked to see someone else, to no avail. “I was ignored and finally I gave up,” said Whitney, who has survived lung cancer and cancer of the urethra and depends on a special catheter to drain urine from her bladder. (An outpatient renal service later changed the prescription.)

Then, earlier this year, Whitney landed in the same emergency room, screaming in pain, with another urinary tract infection and a severe anal fissure. When she asked for Dilaudid, a powerful narcotic that had helped her before, a young physician told her, “We don’t give out opioids to people who seek them. Let’s just see what Tylenol does.”

Whitney said her pain continued unabated for eight hours.

“I think the fact I was a woman of 84, alone, was important. When older people come in like that, they don’t get the same level of commitment to do something to rectify the situation. It’s like ‘Oh, here’s an old person with pain. Well, that happens a lot to older people,’” she said.” CNN 2021

This is not a unique story. In health care older adults are often seen as not competent. If they respond slower in conversations they are considered in cognitive decline and excluded from the decision making process. Physicians ponder if expensive health care resources are still worth it and clinical trials often have age limits. Before you study aging and nutrition considerations in high age, it is important to learn about ageism.

You Will Learn:

0. How do we define old?

1. Ageism refers to stereotypes, prejudice and discrimination based on chronological age

- Dimensions of ageism: Stereotypes, prejudice, discrimination

- Manifestation of ageism: Structural, interpersonal and self-directed

- Expressions of ageism: Explicit and implicit

- Stereotype embodiment takes place over a lifetime starting around age 4

2. Ageism is prevalent in the health care sector

- Ageism in the health sector leads to inadequate allocation of resources, exclusion from decision making processes, and exclusion from research studies

- Ageism leads to poorer health outcomes and a shorter life

3. Self-directed ageism is especially pernicious

- The cognitive model of self-directed ageism has three components: Self-perception of aging, self-doubt, worrying of being negatively judged

- Self-directed ageism is connected to impaired health and well-being

- Reducing ageism can promote positive health behaviors

4. Interventions can reduce ageism and improve health and wellbeing

- Increase intergenerational interactions

- Increase knowledge

- Help older adults to genuinely feel younger

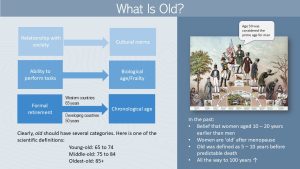

The Definition of Old Has Changed Throughout History

I read an interesting article about defining the beginning of old age throughout history when I prepared for this class (I have posted a link at the bottom of the page if you are interested.) Age has always been used to organize members of a society, and discussions have always been sparked by questions such as who is an adult, when is the peak of life, and what is old age?

For a long time, “being old” was defined by how well somebody functioned in daily life, and from that idea benchmarks were deducted.

Women were considered to age about 10-20 years earlier than men. This stemmed mostly from the inability to bear children after menopause or—as young and fertile was considered the beauty standard back then—the loss of sexual attractiveness. Based on these factors, women were at times considered old after reaching an age of 40–45 years. Men were considered at their peak during those years. Interestingly, the facts are quite the opposite. If women survived childbirth, they outlived men in all societies during all times.

Other times, the “old” benchmark was set about 5–10 years before the predictable death. For example, during colonial times the age of death was between 40 and 65 years. Later, the definition varied with the ability to work, and this varies with occupation. If a job is physically demanding, old age is reached earlier.

The definition of old age is also determined by cultural norms, and may rely on questions such as can the person still contribute fully to society? What are the tasks the society expects? Is the person able to perform job related tasks and tasks of daily life? Is the person still independent? These ideas refer most closely to biological age and the onset of frailty. Cut-offs for being old vary by cultures. While the US tends to have a cut-off at 65 years, in many developing countries this age cut-off for old is set earlier, sometimes as soon as 50 years.

Where does this 65 year cut-off in the US stem from? When the pension system in Western countries was developed, old age was equated with receiving a pension or going into a deserved retirement. The age cut-off was set to 65 years which became the new definition. Today, people live longer and the age of retirement shifts along to ensure that social security funds are sufficient. During the last decades we realized more and more that retirement age does not necessarily describe the starting date for old age.

Setting the “start of old age” to 65 in the US narrowed the definition of “old” somewhat. However, a group of all 65+ year old adults is not a homogenous group. Therefore science developed additional categories. A rough estimate places the young-old from 65 to mid 70s, middle-old from 75 to 85 and then the 85+ as old-old. This chronological definition helps with geriatric research. For example, study participants need to be categorized to allow comparability across different studies. For health care purposes, this definition does not work well. We all know 80 year old people who are more fit than 70 year old people.

While categorizing people into age groups might be necessary it also has a major drawbacks. Categorizing separates groups of people. If those groups become too separated and have little contact with each other it can lead to stereotyping. Stereotyping can lead to ageism which in turn can have real life impact on health.

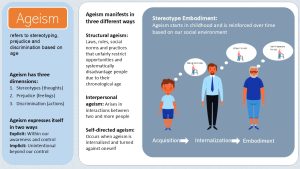

Ageism Refers to Stereotypes, Prejudice and Discrimination Based On Chronological Age

Ageism is a lifelong process informing how we see aging. Ageism describes our stereotypes, prejudice and discrimination based on the chronological age of a person. In short how we think about, feel about and ultimately act with older adults. Keep in mind that ageism refers not only to older adults but can affect all age groups. In this chapter we will focus on older adults though.

Aging is a natural, very individual process and the older we become the more different we will be from younger age groups. Categorizing people into broad age groups is a natural process. Ageism takes place when people are categorized by age and this categorization leads to disadvantage and discrimination.

Age related views and attitudes are a direct reflection of the environment we grow up and live in. A person growing up in an environment where interaction with elderly people is normal and where aging adults are valued for their wisdom, life-experience and contributions to society, will harbor fewer negative views towards aging. Scientifically we split views about aging into three dimensions.

- Stereotypes are our thoughts and beliefs about aging and the older adult.

- Prejudice are our feelings about the aging process or older adults.

- Discrimination is the action based on our stereotypes and prejusdice.

All three dimensions can express themselfs either explicitly or implicitly. Explicit ageism is expressed with awareness and control. For example, a physician might look at the pros and cons and then withhold an expensive treatment. The physician might reason that the older person might not live long enough to make the treatment worth the cost. Implicit ageism is unintentional and beyond our control. Medical students might choose not to apply for an geriatric residency because of their fear of aging.

Ageism manifests in three different ways:

- Structural ageism refers to societal policies and practices that systematically disadvantage older adults. Older adults might be passed over for a promotion at work or not being hired for a position they are well-qualified for.

- Interpersonal ageism describe the negative interaction between two or more individuals. The younger person might oversimplify instructions for how to use a new cell phone assuming that the other person is too old to understand technology.

- Self-directed ageism is established over a lifetime. It occurs when we internalize stereotypes and prejudice we learned from our culture and social environment. An aging adult might have learned over a lifetime that older people will decline cognitively and physically and therefore will be unable to learn new knowledge and skills. If this belief is internalized the older adult might not take up a new hobby no matter how fun and enticing it seems because they believe they are not able to learn the new skills needed.

How is ageism internalized? The stereotype embodiment theory provides an explanation. Starting at the age of four we form a picture of what being old means. Opinions and views in our social environment, our level of interaction with elderly people and our knowledge about aging contributes to the formation of this picture. These acquired stereotypes start to determine how children feel about older people and how they behave when interacting with older people. This phase is called stereotype acquisition.

The more negative believes we collect in our teens and young adulthood the faster ageist views are internalized starting in midlife. We have expectations how we should act and feel at certain life stages. People with negative views tend to feel that they are aging faster. Interestingly, changes in our cognition foster this maintenance of negative or positive views of aging (see grey box).

What happens to cognition during aging?

As we age we store increasing amounts of information in our brain. This changes how our brain has to retrieve and use information. Cognitive sciences shows that crystallized intelligence, a person’s general knowledge, vocabulary, and reasoning based on acquired information, is increasing with age. We increasingly make decisions based on our life time of experience. In contrast fluid intelligence, the rapid aquiring of information, reasoning and problem solving without existing knowledge, is declining. As we age we become more cautious. Middle-aged and older adults tend to be more risk averse, volunteer less for re-training in work settings, or have an increased awareness of potential failure. Overall, it might take a little longer but middle-aged and older adults are fully able to solve problems and learn.

By the time we become older adults these internalized stereotypes can become a self-fulfilling prophecy. We start acting according to those stereotypes which is called embodiment. This is called self-directed ageism.

Keep in mind that some of the most common ageist believes—the decline in physical strength and memory—are founded in reality. But, the views and beliefs are exaggerated and can lead to overt discrimination of aging people.

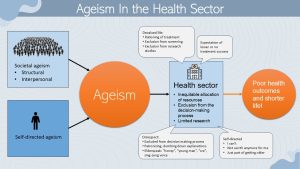

Ageism Is Pervasive In the Health Care Sector

Structural ageism can be found across many institutions and is prevalent in the health sector. Research has identified three areas of ageism in the health sector.

- Inequitable allocation of resources: Health care rationing is a common practice. Age determines who is receiving medical procedures. This can range from life-sustaining treatments such as ventilator support, surgery or dialysis to referrals to exercise or nutrition programs. The idea behind the rationing tends to be that limited resources will have better health outcomes in younger and healthier people.

- Exclusion from the decision-making process: Health care professionals often act condenscending and patronizing. Explanations are dumbed down so the older adult does not receive all facts to make an informed decision. Health care providers might use elderspeak, overly short, child-like sentences, sing-song voice and endearing names. The use of elder-speak treats the adult person as a child discouraging full participation in the decision making process. The message is send that the older adult is too old to make their own health care decisions.

- Exclusion from scientific studies: Many scientific studies have an age limit for enrollment. This is especially cynical since many conditions are more prevalent in older people. Therefore research regarding efficacy and safety of treatments is missing for older people.

The research exploring if health professionals hold ageist attitudes and beliefs is limited. It is unclear how prevalent interpersonal ageism is in health care. Anecdotal evidence seems to support it. Studies show though that some health care providers are not sufficiently trained to work with older patients. In general gerontology is one of the least desired specialization in the medical field. Consequentially, well-trained medical, health and social workers are lacking especially in long-term care of older people.

Between rationing of care, uncertainty of the efficacy and safety of medical treatments, lack of well-trained health care provider in gerontology and potential interpersonal ageism, it becomes clear that ageism in the health sector is associated with reduced well-being in older adults and a shorter life.

Let’s Stop and Explore Our Own Attitudes Towards Aging

While the Harvard Implicit Association Test is controversial as a scientifically precise tool to determine bias, it is a great start to explore your own personal ageist attitudes. Follow the link and explore your own bias.

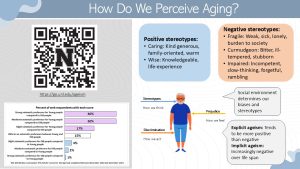

Each individual person will have a different life experience leading to very individualized thoughts and feelings about aging and older adults. But, positive and negative stereotypes can also vary from culture to culture. In the US positive stereotypes include older people being warm, caring and family-oriented, knowledgeable and experienced. On the other hand negative ageist stereotypes range from being fragile, sick and lonely to being bitter, ill-tempered and stubborn. The most common stereo types are being physically impaired and having declining cognitive abilities.

Interestingly, explicit ageism tends to be more positive while our implicit ageism becomes increasingly negative as we age.

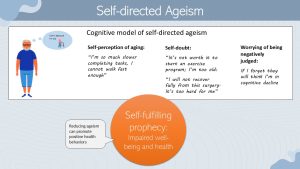

Self-Directed Ageism Is Espcially Pernicious

When scientists research the impact of age discrimination they consistently come to an interesting conclusion. The overt interpersonal and institutional discrimination impacts health but it is still a minor factor compared to self-directed ageism. Self-directed ageism happens when stereotypes, negative views and biases are internalized and ultimately embodied. Studies show that self-directed ageism tends to accelerates after age 70. How does that happen?

The cognitive model of self-directed ageism is a good scientific explanation. Self-directed ageism has three components: Self-perception of aging, self-doubt and worrying to be negatively judged.

A negative self-perception of aging prevents us from living fully. People tend to compare their current selves against their past selves. They might notice their aches and pains and conclude that they are not as strong, as fast or as mentally agile anymore. They might become easily frustrated when completing tasks because they are not as fast or strong as they used to be. They might not even try or learn new activities because it is not worth it anymore. Due to the frustration those individuals feel that they subjectively age faster than they do in reality.

Self-doubt will prevent people from trying. For example, these people might not work hard on their recovery after a surgery or an infectious disease. It might not be possible to motivate them to start an age-appropriate exercise program because they feel they are not able anymore.

Lastly, people with self-directed ageism will worry that they are negatively judged. They might be slower to complete a task, forget to take their medication and are worried that others think they are in cognitive decline. Being afraid of making mistakes adds to daily stress and impacts the ability to live life to the fullest.

Self-directed ageism tends to be a self-fulfilling prophecy. People act to match their stereotypes and negative views about aging. They are less likely to start new healthy behaviors or maintain a healthy lifestyle. They might not seek out treatment or adhere to the treatment because it is not worth it anymore and I cannot do it anyway. The consequence are impaired wellbeing and health.

Studies show that reducing ageism, outward and self-directed, will promote positive health behaviors.

Can ageism explains everything?

As humans we tend to look for simple explanations. The stereotype embodiment theory and the cognitive model of self-directed ageism are an elegant approach to explain the health impact of ageism. It’s not that simple though. Another approach to explain reduced confidence and self-efficacy is coming from neurocognitive research.

Starting in middle age people tend to be more reluctant to retrain in work settings because they have less confidence in their ability to learn new tasks and express an increased fear of failure. This reduced metacognition and self-efficacy could be due to self-directed ageism or neurocognitive changes. Or both. The research is not conclusive at this point. Most likely (as always) functional decline and decline of wellbeing and health during aging is a multifactorial, individual process.

A new explanatory model combines neurocognitive research results with ageism research. Biological adaptions of the brain due to aging lead to a increased reliance on prior knowledge, accumulated general world knowledge. This means that tasks and decisions are not based on a mix of new and old information but the aging brain relies more on experience and life-long knowledge. It is easy to imagine how this adaption increases the maintenance of negative stereotypes learned and internalized in younger years. It’s harder to break through the cycle of self-directed ageism as our brain ages.

In addition, older adults profit from a supportive environment. Our fast-paced environment with multiple environmental stimuli make it more difficult for older adults to function at their highest capacity.

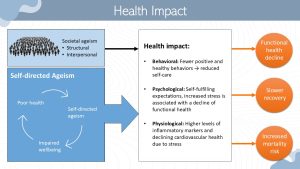

The question is now how exactly ageism reduces wellbeing and health and even shortens life. As you learned at the beginning of the chapter there are two main components of ageism. External sources and self-directed ageism. Keep in mind though that structural ageism fuels self-directed ageism.

When scientists research those two components self-directed ageism has as much larger impact on health. Self-directed ageism reduces wellbeing which in turn leads to poorer health. People with poor health and chronic diseases tend to have a high degree of self-directed ageism. That way they are in a vicious cycle of declining health.

Health is impacted three ways, behavioral, psychological and physiological. A negative self-perception of aging and self-doubt will impact health behaviors resulting in reduced self-care. People might not see a physician on a regular basis, might not start new healthy behaviors such as a strength training program or might not follow treatment plans.

Ageism impacts psychological health. Self-fulfilling expectations increase stress due to a decline in functional health which reduces the ability to perform daily tasks essential for complete physical, mental and social well-being. Aging is in general associated with a reduced resilience when experiencing stress, but studies have demonstrated that feeling younger—reduced self-directed ageism—is a stress buffer. As you know chronic stress alters hormonal signaling and metabolic health impacting physiological health. Chronic stress contributes to systemic inflammation, hypertension, and atherosclerosis. This accelerates the development of chronic diseases taking place during the aging process.

As a result functional health declines, recovery from adverse life events decreases and mortality risk increases. This way ageism has not only consequences on mental health, but is impacting longevity and life quality.

Interventions Can Prevent Self-Directed Ageism and Improve Well-Being and Health

Interventions combatting self-directed ageism are in their infancy. The most effective solution is to fundamentally change the perception of aging in our society. First we need to change how we message aging and focusing on wisdom, worth and contribution to society. Designing health policy to improve the perception and status of older adults in our sociaty is the basis of interventions.

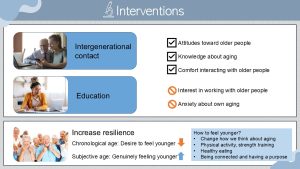

Next we need interventions targeting individuals. Successful interventions involved increasing intergenerational contact and knowledge about aging. These interventions—up to 12 weeks long—improved attitudes toward older adults, knowledge about aging and comfort interacting with older adults. Increasing intergenerational contact seemed to have a shielding effect against ageism. The interventions were more effective when working with teens, young adults and women.

Frustratingly, the interventions did not increase an interest in working with older adults and did not reduce anxiety about the participants own aging. Given that ageist attitudes are acquired in youth and internalized over a lifetime ageist structures in our society we have to admit that interventions can reduce ageism but not eliminate it.

The second approach addresses self-directed ageism directly. Older adults experiencing the least amount of self-directed ageism tend to feel genuinely younger and are proud of their own age group. This should not be confused with people desiring a younger chronological age. This population group experiences more self-directed ageism, harmful to wellbeing and health.

So, how do we make people genuinly feel younger? Interventions aiming at making older adults feel younger should help disrupte the cycle between self-directed ageism and health. We can start with younger adults and hope that aging in a age-positive environment with lots of interactions between generations will slow down the development of self-directed aging.

Functioning well in daily living will also increase confidence and the feeling of being younger. Another good argument to help older people start physical activity programs and help them find an enjoyable healthy eating pattern.

Interested In More Information?

1. Global report on ageism. World Health Organization. March 18, 2021. Accessed October 29, 2024. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240016866.

2. Henry JD, Coundouris SP, Craik FIM, von Hippel C, Grainger SA. The cognitive tenacity of self-directed ageism. Trends Cogn Sci. 2023;27(8):713-725. doi:10.1016/j.tics.2023.03.010

3. Covey HC. The definitions of the beginning of old age in history. Int J Aging Hum Dev. 1992;34(4):325-337. doi:10.2190/GBXB-BE1F-1BU1-7FKK, https://pubmed-ncbi-nlm-nih-gov.libproxy.unl.edu/1607219/ (you need to go through the UNL library system to PubMed to have access)

Feedback/Errata