2 Down the Wrong Path: Weight Stigma and Discrimination

Sabine Zempleni

When I look around my classroom the overwhelming majority of students is young, physically active, exercising regularly and eating somewhat healthy. Living and studying nutrition, health and exercise makes it so easy to shift the blame for obesity to the individual person and build up stereotypes about people with a higher weight. If I and people around me can do it with knowledge and discipline, everybody else should be able to live a healthy live.

It’s easy to fall into this trap. So, before we delve deeper into chronic diseases and later the life stages and sensitive periods, I would like everybody to stop and spend one class learning and thinking about weight discrimination. Start out by allowing people with obesity to share their experience with weight discrimination (HBO documentary The Human Cost of Obesity):

You Will Learn:

1. A healthy weight is not what Instagram or TikTok tells us.

- What is healthy weight from a scientific standpoint? It is extremely complicated to determine for an individual person.

- Easier to answer: Ripped looks increase the risk of having an unhealthy, low body fat percentage.

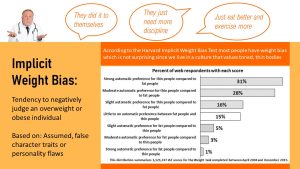

2. Almost everybody has implicit weight bias.

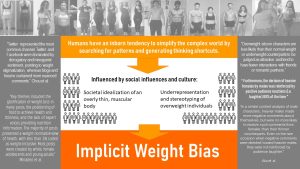

- Humans are vulnerable to implicit biases because we need to make sense of the complex world by finding patterns and creating cognitive shortcuts.

- Social and cultural influences contribute to implicit weight bias.

- It is important to understand your own weight bias: Take the Weight IAT.

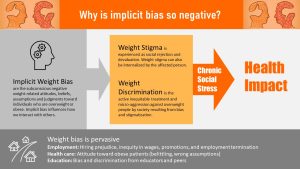

3. When implicit weight bias becomes weight stigma and discrimination people are harmed.

- Implicit weight bias starts out subtle but if unchecked can progress to explicit bias and ultimately leads to weight stigma and discrimination.

- Weight stigma can be constantly experienced in the world around us or can be internalized.

- Experiencing weight stigma is connected to poor health.

4. Health care professionals should know better, but weight stigma is pervasive in all health care disciplines contributing to poor health.

- Explicit and implicit weight bias is documented for all health care disciplines.

- Explicit and implicit weight bias in health care is connected to less time with the patient, less patient-centered communication, less patient education, even avoiding some examination types.

- Existing weight bias interventions address education about causality and controllability of obesity, evoking empathy and addressing social norms.

A Healthy Weight is Not What Instagram Or TikTok Tell Us

During the last chapter you learned about the physiological consequence of growing adipose tissue stores, the altered hormonal signaling and the increasing systemic inflammation. On purpose, I focused on the physiology and did not attach specific BMI ranges or body fat percentage numbers. The reason for this approach is that our idea of what is a healthy or optimal weight is extremely warped.

Take a minute and think about what image comes up when you think about healthy weight.

For most people the image of optimal weight is informed by the media and during the recent decades by social media. Influencers who train and eat as a full-time job pose as normal, healthy everyday people and set unattainable expectations. The other extreme is the often heard statement Everybody is different and has their own optimal weight. This approach is vague and not very helpful either.

What Is Healthy Weight From a Scientific Standpoint? It Is Complicated to Determine For an Individual Person

As a first step lets think about what healthy weight is. Per scientific definition healthy weight is a number that indicates a low risk for weight-related diseases and conditions.

You might have noticed that I wrote “number”. Scientists are still discussing what that number is and what tool we could use to screen for this optimal weight.

When we step on the scale we get pounds or kilograms and that is not very helpful since weight needs to be related to height. This is where the BMI comes in bringing the weight in relationship to height (see review slide in chapter 1).

Not perfect either. The BMI takes height into account but does not include information about amount of bones, muscles and fat. We all have read about the 6-foot basketball player who is according to his BMI obese and supposedly at high risk for disease. In reality he just happens to have large muscles.

When we use the BMI we need to keep in mind that the BMI is purely a risk measure for weight-related diseases and needs to be used correctly. The BMI is not for people with a large muscle mass, for young children, seniors, very short and very tall individuals. For everybody else the BMI is a reasonable good tool if we apply it correctly: Screening for disease risk and prompting an exploration of physical health and lifestyle if the BMI is too high.

The third way to determine a healthy weight is to combine BMI with waist circumference because this gives us an idea how much central fat somebody is carrying. As you have learned in the chapter before central, especially visceral fat, is by itself a risk factor for chronic diseases. Using a measuring tape we can gauge the abdominal fat mas.

The fourth approach is to determine the fat mass. This is the most precise indicator but difficult to determine in a physician’s office or at home. Determining fat mass will require either extensive equipment such as DEXA or a skilled person measuring skinfold thickness using a caliper. Recently, smart watches determining body fat might get us a step closer to using body fat instead of BMI. The measurements a re fairly accurate to gauge a person’s body fat, especially over time. For scientific purposes the watches are not accurate enough.

For all measurements you will find formulas to determine a healthy target weight. But, this seemingly precise healthy or optimal weight is contentiously discussed. That is why it is often recommended to combine anthropometric measurements with biological markers for any developing weight-related diseases.

Here is another problem. The formulas for healthy weight were modelled based on population data. Scientists tracked weight and weight related health outcomes for large populations. Then the scientists calculated the average weight, BMI, waist-circumference or fat percentage range with the lowest weight-related disease risk. In the case of the BMI this would be between 18.5 and 24.9.

The resulting healthy weight works well if scientists use it in a scientific setting evaluating the weight distribution in a similar population, comparing average with average.

But, individual people are not average. While the formulas spit out an average healthy weight some people will not develop chronic diseases being on a higher weight while others will develop chronic diseases even on a healthy weight.

Interestingly, the Dietary Guidelines tried to define what a healthy weight is and who needs to lose weight since 1990 when the term healthy weight was first coined. Back then healthy weight was defined as a combination of weight, body composition, fat-distribution and weight-related medical conditions.

This is a complicated definition and in 1995 the term healthy weight was replaced with a table of weight ranges, just to be revised in the 2000 Dietary Guidelines to a set of medical risk factors that would indicate a need for weight loss.

You can see the trend here. Healthy weight is hard to define in a simplistic manner. The newest Dietary Guidelines from 2020 avoid a clear definition altogether and focus more on life-long healthy eating and an active lifestyle. For the tricky weight loss topic readers are now referred to the CDC website.

The CDC website uses the BMI categories and defines a BMI between 18.5 and 24.9 as healthy weight. The webpage also uses waist circumference. Keep in mind that we simply lack a better simple assessment method everybody can do at home.

It becomes clear that health professionals like to use the term healthy weight but what that means for an individual person is somewhat elusive.

Easier to Answer: What Is Not a Healthy Weight?

It is much easier to answer what is not a healthy weight. There are plenty of studies looking at body composition and health outcomes. From those studies we know that a certain amount of body fat is necessary to support health. We also know that weight in obesity grade 2 and 3 (BMI over 35 or 40) is increasingly likely to be connected to health issues.

Once people become severely underweight hormonal changes take place that signal the body a food shortage. Energy resources are directed toward survival leading to reproductive problems, muscle wasting, immune system issues and poor bone health. You will learn more about the physiology in other chapters.

For men an minimum body fat between 3 and 5 % is necessary to stay healthy. Women have a higher body fat minimum, over 12 %, due to higher fat content of reproductive organs. A body fat percentage ensuring good health and nutrient stores in case of disease is much higher: 8 – 24 % for men and 21 – 35 % for women.

Now, let’s compare that to the idealized influencer body. For a ripped look men and women tend to be under the healthy body fat percentage and above the minimum. This is not ideal but acceptable from a health standpoint. Once body fat drops into the competition look—this is often the look influencer and body builders work towards for photo shoots—both men and women have to lose almost all subcutaneous fat and slip under the minimum body fat range. Only then muscles are truly defined.

The problem is that what you see on TikTok is a competition look. The influencers take extreme dietary and exercise measures to lose the last subcutaneous body fat so muscles are very defined. After the photo shoot the influencers return to a more normal life. In addition, most pictures and videos are staged so the person looks thinner and then photoshopped for a perfect picture.

In conclusion, scientifically we understand the connection between body weight and weight-related diseases on a population basis. Determining the healthy body weight for an individual person is much more complex.

The scientific knowledge is opposed by the cultural perception of an ideal body weight and body shape, influenced by the pictures and videos of content creators and athletes. This societal ideal is definitively not a healthy weight.

Even worse, this ideal has consequences for how we perceive body size and shape and ultimately how we perceive other people.

Almost Everybody Has Implicit Weight Bias

Per definition implicit weight bias is the tendency to judge overweight and obese individuals in a negative way. The judgment is not based on a concern for the health of people but being overweight or obese is associated with false, negative character traits or personality flaws.

Terminology: Implicit and Explicit Bias

Implicit and explicit bias taps into two different information processing systems in the brain.

Implicit bias uses the brain’s unconscious, fast and emotional thinking system. Many everyday activities are guided by this system. For example once we learn how to drive a car we do not think much about the how. We just do it. The same goes for implicit biases. We tend not to be aware of them and just react subconsciously to something we experience. Implicit bias might even run counter to a person’s conscious, rational believes.

On the opposite end are explicit biases. These are guided by the second thinking system of our brain which is slow, effortful and conscious. When we express out explicit biases we do it based on our beliefs and we are very aware of what we are saying and doing.

Most of the time implicit and explicit bias are distinct but we should keep in mind that implicit bias can become explicit bias. This happens when we become aware of our implicit biases and make a rational decision to act on it.

Social psychology has studied why people develop implicit biases and have come up with a construct.

There are three tendencies that make humans vulnerable to implicit bias:

- The world is complex and chaotic. In order to make sense of what we see, feel and hear, we tend to look for patterns and associations. When it comes to other people this tendency allows us to identify a group of similar people and we feel better being part of a group. That way we also distinguish ourselves from others. Studies showed that even small children notice how they are similar and dissimilar from others. Forming these patterns of similarities and dissimilarities influences how we see others and contributes to the development of implicit bias.

- The brain also tries to simplify the complex world by taking shortcuts. When we see A we expect B to happen. We have a tendency to take these shortcuts even if the situation is much more complex. Implicit bias is one of those shortcuts gone wrong. For example, when we see a person who looks fit and trim we expect that this person is disciplined and can get a lot accomplished.

- The last contributor are social and cultural influences. The environment you grow up in, family, friends, communities, tend to determine what you think about others especially about people who does not belong to your group. Here is where media and social media come in. While a child is initially mainly influenced by the parents and family, once the child grows up and spends time away from their parents, teachers and friends modify those believes. Today, movies, shows and social media are ubiquitously available and have a large influence on the development of implicit bias.

I thought it would be interesting to test your own weight bias.

A popular test that is coincidentally available online for everybody to take is the Implicit Association Test or IAT for short.

It is an interesting experience but keep in mind that the validity of this test is discussed when it comes to scientific use. For us exploring our own weight bias the IAT will work just fine.

When you follow the link you don’t need to enter your email. Click on PROJECT IMPLICIT SOCIAL ATTITUTES, agree to proceed, and then find the weight IAT. Follow the instructions.

You should not worry about your results. The results from the weight IAT you see in the infographic above shows that the majority of people taking the weight IAT prefer thin people compared to fat people. Just be open and find out where the test takes you. Much more important is that we become aware of our implicit biases and find ways not to act on them.

When Implicit Weight Bias Becomes Weight Stigma and Discrimination People Are Harmed

We established that most people have implicit weight bias. The question is: Do you let your implicit weight bias influence your interactions with others? Do you act on it? Be gentle with yourself. It is hard to change implicit biases since they are a quick, subconscious reactions and we often don’t notice that we are biased.

Why is it so important to become aware of our implicit biases? Implicit weight bias might be subtle but has far-reaching consequences. Think back to the video you watched at the beginning of this chapter. The people in the documentary described impactfully how they experience the fallout of implicit weight bias. Since implicit weight bias—and explicit weight bias—is so pervasive there is no getting away from reactive facial expressions, insensitive remarks and unfair, judgmental decisions.

Weight stigma, which is defined as a social rejection and devaluation of people who are outside of the prevailing social norms for body size and shape, affects people with obesity in several ways.

Thoughtless remarks generate stress but so does the constant expectation of being devalued, ostracized and criticized. Since weight bias is so pervasive in our society it can happen at any time, any place, even when interacting with family and friends.

In addition, people with a higher weight have to deal with outright weight discrimination. This includes being subjected to microaggressions, such as people moving to a different seat when an obese person sits down, all the way to inequitable treatment. In the work place inequitable treatment can mean that a weight-normative person is hired over the person with a higher weight, that the person with obesity is not promoted due to the wrong assumption that this person is not as hard-working, disciplined and resilient. Inequitable treatment is also researched and discussed in education and health care settings.

Many people with obesity also internalize the societal standard for body size and shape and turn the learned weight stigma against themselves leading to self-blame and feeling ashamed of their body size and shape.

At this point you can probably easily imagine that being daily confronted by implicit and explicit weight bias, weight stigma and outright discrimination is very stressful. The stressor is not only coming from the impact of the social situation but also constantly anticipating weight stigma.

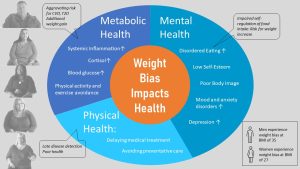

Several pathways connect weight stigma, either pervasively experienced or internalized, to poorer health.

Mental Health: Being under constant chronic social stress will reduce mental health. People experiencing weight stigma are more likely to experience mood and anxiety disorders and are at a higher risk for depression. Individuals with obesity who internalized weight stigma are at risk for disordered eating such as binge eating. There is also evidence that people experiencing weight stigma have a higher risk for continued weight increase.

Metabolic Health: Chronic stress leads by itself to increased cortisol levels and systemic inflammation. Those stress-related metabolic changes by themselves increase the risk for cardiovascular disease for example. The hormone cortisol also increases appetite and blood glucose levels. Studies showed that participants manipulated to experience weight stigma increase eating and have a decreased self-regulation of food intake. While the weight stigma research is still evolving there is evidence that the experience of weight stigma aggravates poor metabolic health.

Health Care and Prevention: When people internalize weight stigma they are less likely to participate in health prevention activities. They are less likely to be physically active or exercise regularly. Dietary interventions tend to be less effective. When patients experience weight stigma in physicians’ offices they are more likely to delay medical treatment and avoid preventative care or disease screenings. Diseases are later diagnosed and therefore often harder to treat.

In conclusion, experiencing weight stigma is connected to poor mental health and surprisingly to lower metabolic health independent of the adipose tissue size. Experiencing weight stigma in health care settings is connected to avoiding preventative care and medical treatment reducing health even further.

Health Professionals Should Know Better, But Many Participate in Weight Discrimination Contributing to Poor Health

Before we explore how the provider’s implicit and explicit bias impacts the quality of health care, lets have a look at how weight discrimination is build—often unnoticed—into the health care experience.

Many of us, independent of weight, dread the trip to the scale at the beginnings of each physician visit. Stepping fully clothed on a scale will lead to unexpected results. Now imagine you are a patient struggling with weight.

The way a patient visit is set up can determine if the patient has a positive or negative experience. This includes designing the waiting area and treatment rooms with furniture that fits people of all sizes. Some studies also report that undressing for examinations such as breast exams can be an humiliating experience for women. Tiny dressing cabins might not have the appropriate size to move around without bumping into partitions or privacy is lacking entirely.

Explicit and Implicit Weight Bias is Documented For All Health Care Disciplines

Weight bias in health care has been studied for more than three decades. Current evidence supports that provider weight bias can be found in all health care disciplines. Studies are available for physicians, physician assistants, nurses, dietitians, physical therapists and exercise physiologists. Even providers specializing in treatment of obesity display weight bias.

Providers commonly assume that patients with a higher weight are less compliant and less successful when following treatment plans because they are considered lazy, unmotivated, gluttonous, or even less intelligent than their counterparts with a lower weight. It is easy to imagine how this implicit or sometimes explicit bias can impact treatment.

If a provider makes these assumptions than the patient seems not to be worth the time quality treatment takes. Providers think that limited time and effort can be spend with more promising patients.

Studies show that health care provider spend less time if the patient is obese and engage less in patient-centered communication, ignoring patient concerns and behaving condescendingly. There are even study results indicating that unrelated symptoms tend to be contributed first to obesity, followed by a recommendation of weight loss before other treatment options are explored.

Studies also show that providers spend less time educating patients. Obesity treatment is oversimplified and weight loss goals tend to be unrealistic.

For example a study assigned patients with lower and high weight randomly to physicians and timed the visit. The physicians spend in average 28 % less time with the higher-weight patients.

Some physicians even avoid exams they consider unpleasant to conduct in patients with obesity such as pelvic exams for women.

When studies survey patients with obesity about their experience, patients were concerned that physicians and other healthcare providers avoided recommending weight loss interventions and felt their healthcare provider did not have a good understanding of the causes and consequences of obesity.

Surveyed physicians felt not equipped to work with obese patients and were not likely to refer the patients to a weight loss program or counseling. This situation is aggravated by the fact that insurance companies do not reimburse for obesity related treatment such a working with a dietitian or personal trainer. Only if the patient has co-morbidities such as T2D, nutrition counseling is reimbursed.

It is easy to imagine that build-in weight bias at provider offices is impacting the patient-provider relationship leading to avoiding preventative visits and delaying treatment. Diseases and conditions are diagnosed late and inefficiently treated. The consequence is the increased risk for poor health.

Existing Weight Bias Interventions Address Education About Causality and Controllability Of Obesity, Evoking Empathy and Addressing Social Norms

Even if the evidence is still slim we cannot wait. Each current or future health care provider can start by learning and generating awareness that there is a problem. Designing inclusive provider offices or modifying existing ones can be a first step. Designing a positive patient experience for all—health care providers can ask for patient feedback—would be another step.

The Science: Effective Weight Bias Interventions and Training Are Lacking

Despite decades of research this is still a new field of research. We understand that weight bias and discrimination exists in all health care disciplines but comparable quality studies supporting effective interventions are lacking.

At the moment the scientific discussion surrounds how to measure weight bias consistently. Results from different studies are hard to compare because the studies use several different survey tools. In addition, some of the popular tools (for example the weight IAT) don’t measure implicit weight bias as reliable as we would need for a scientific study.

At the top of the scientific wish list is therefore a reliable survey tool to measure implicit and explicit weight bias. The development of such survey tools can take a long time, years. The process of developing the tool involves conducting large studies interviewing patients how they experience weight bias. The next step would be to develop questionnaire items that need to be pre-tested in other studies. Based on the results of multiple studies a questionnaire can be developed which again needs to be tested so it measures accurately, is sensitive enough and is reproducible in a variety of situations. This process will take many studies over many years. Once a measuring tool is developed the research can progress to identifying the consequences of weight bias and develop interventions.

The existing interventions to reduce weight bias in health care settings address three areas.

Education about the causality and controllability of obesity: Many health care provider still assume a personal responsibility for obesity. Today, we know that reasons why people become obese are complex and that weight loss maintenance is extremely difficult. The hypothesis is that understanding this complex physiological, psychological and environmental situation will reduce weight bias. This type of training aims at students but it would be important to educate practicing providers as well.

Evoking empathy: Other training programs or documentaries like the one you watched use storytelling techniques to help people understand how weight bias is experienced. The hope is that empathy and understanding will nudge people to work on their weight bias.

Addressing social norms: Weight bias is ingrained in our society as weight stigma and weight discrimination. These type of interventions work on reducing weight stigma and active discrimination. Keep in mind that people with obesity are not protected from discrimination by the law. Tiny airplane seats and legroom, or workplace discrimination are just a few examples. Shifting societal norms and advocating for weight-inclusive public policy and laws addresses weight bias on a larger scale.

Communication Matters:

- Treat obesity as a condition, not as a personality trait: Instead of obese person -> person with obesity

- Don’t just assume; involve patients: How do you feel about your weight? Would you be willing to have a discussion about your weight today?

- Don’t shame and blame into cooperation. Instead ask: What do you think are the reasons why you have trouble starting to exercise? What can I do to help you get started?

Weight bias should be a part of the education of future health care providers. This should include for example:

- Education about obesity as a disease (here it is again) and not a personal lifestyle decision.

- Sensitive communication training

- Virtual reality applications allowing providers to practice weight-inclusive communication and interaction with patients.

So far studies testing the efficiency of interventions have seen a small to modest reduction of implicit weight bias. Keep in mind that the research in this area is just starting. In the meanwhile we all can work on our implicit weight bias and educate others.

Lastly, physicians need to be aware that they are not educated to start the weight loss process and guide patients through weight loss and weight maintenance. Treatment of obesity needs to be personalized with the patient in charge. Dietitians (nutrition side) and personal trainers (physical activity and exercise side) are better equipped to design personalized plans.

Feedback/Errata

5 Responses to Down the Wrong Path: Weight Stigma and Discrimination