35 Energy Balance

Sabine Zempleni

In the US rates of overweight and obesity are still rising. In 2020 42 % of Americans were obese and half of the American population reports to be on a weight loss journey. On the other hand a culture of constant food tracking has emerged. How does our body know how much to eat? Is it necessary to track all our food with an app to maintain a healthy weight? During this chapter you will explore the components of the energy balance, how we determine healthy weight and learn about weight gain, loss and weight maintenace.

You will learn:

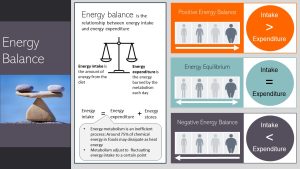

1. Energy balance is the relationship between energy intake and energy expenditure.

-

- There are three states: Energy equilibrium, negative and positive energy balance

- The energy expenditure has several components:

- Basal metabolic rate (RMR)

- Physical activity divided into NEAT and exercise

- Thermic effectof foods

- Cold-induced thermogenesis

- Health disparity: In the US Native Americans, Black Americans and Hispanic Americans are most affected.

2. Determining a healthy weight is more complex than stepping on a scale.

-

- BMI: Determining disease risk

- Body composition

- Fat mass and fat free mass

- Lean body mass

- Body fat distribution

- Determining body fat

3. Successful Weight Loss Is Not a Question of Personal Discipline.

-

- Regulation of the energy balance

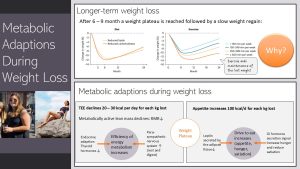

- Metabolic adaptions during weight loss

- Weight loss maintenance

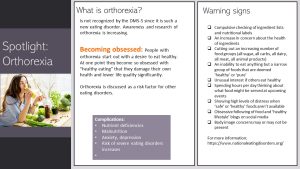

4. Orthorexia: When Healthy Eating Becomes an Obsession

The images in this chapter are included under the provisions of fair use under U.S. copyright law (non-profit, educational use).

1. Energy Balance Is the Relationship Between Energy Intake and Energy Expenditure

On the most basic level, energy balance describes the relationship between energy intake from our daily meals and the energy our body uses, called the energy expenditure. When energy intake equals energy expenditure our weight is stable.

The metabolic state when energy intake is higher than the expenditure is called positive energy balance. The additional energy is stored as glycogen (glucose storage) or fat in the adipose tissue. Weight increases.

If the energy intake is lower than the energy expenditure the metabolism taps into the energy resources. Weight will decrease.

While this premise of the energy balance is in principle correct it does not work 100 % like that. Our body is extremely energy inefficient. Food energy is converted into ATP and the ATP is used for muscle contractions, pumping minerals across cell membranes, transporting, synthesizing and so much more. Only 25 % of the chemical energy in our food is used to move and maintain our bodies.

75 % is lost as heat energy. This also means that the metabolism can become more energy efficient if necessary. For example, if you are fasting metabolic adaptations will increase the energy efficiency and you will be able to complete the same amount of work using less energy. On the opposite end if you eat slightly more than usual the metabolism will slightly increase the BMR and heat production.

That way our body maintains body weight, called set-point weight. Only if the energy imbalance is consistently positive or negative our body will increase or decrease weight.

The Energy Expenditure Has Several Components

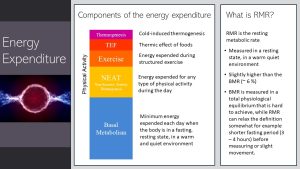

The energy expenditure has four main components:

- Basal metabolic rate: Energy expended when the body is in a fasted—over 12 hours of no food intake—resting state (no movement, lying still) in a warm, quite environment. When scientists measure BMR the long fasting period makes it necessary to start the test in the morning which complicates research. Therefore there is also a relaxed version of the BMR, the resting metabolic rate or RMR for short. The RMR is still measured in a resting position in a warm quiet environment but the fasting period is shorter (3 - 4 hours) and slight movement is allowed. The RMR is about 6 % higher than the BMR. If you are not an athlete the BMR is the largest component of the energy expenditure.

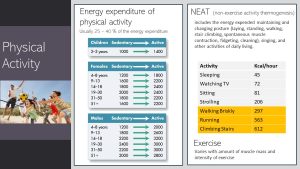

- Physical activity has two sub-components. NEAT or non-exercise activity thermogenesis is any type of light physical activity during the day while exercise related energy expenditure refers to structured exercise.

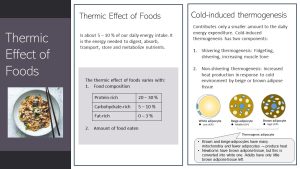

- TEF or thermic effect of food measures energy used to digest, absorb and metabolize food.

- Cold-induced thermogenesis refers to energy use to keep the body warm during cold temperatures.

The BMR or RMR are measured using either direct or indirect calorimetry. During direct calorimetry the person is placed into a small room, the metabolic chamber. The heat the body radiates is measured and then converted into kcal. Indirect calorimetry uses a mask to measure oxygen uptake and carbon dioxide exhalation and calculates energy use from those results.

The BMR and RMR include the energy use of organs such as liver, brain activity, heart pumping blood, kidneys producing urine. Even the skeletal muscles need to maintain homeostasis during rest which requires ATP. The largest amount of energy during rest is expended by the liver followed by the brain.

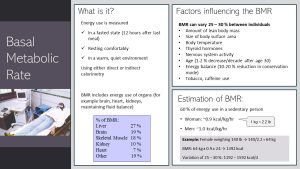

The BMR can vary 25 to 30 % between individuals. We all know people who eat large amounts and never gain weight while others constantly struggle to maintain body weight.

Some factors influencing the BMR/RMR are non-modifiable. Non-modifiable factors are:

- Age: After age 30 the BMR declines slightly but steadily (~1-2 % per decade). Part of the decline can be attributed to a loss of muscle mass, but there is also decline due to aging.

- Biological sex: Size matters when it comes to the BMR. A taller person will have a larger body surface resulting in a higher BMR. Higher lean mass and larger body surface means that men have a higher BMR than women.

- Genetics: Height, thyroid hormone production, nervous system activity and body temparature can all vary individually. The taller a person is the higher the BMR. The regulation of thyroid hormone secretion by the thyroid gland can up and down regulate the efficiency of the energy metabolism (40 - 50 %). Some individuals have genetically higher or lower thyroid hormone production. Nervous system and body temperature need energy. The more activity the higher the BMR.

- Growth: Growth spurts in children will increase the BMR. The same applies to tissue growth during pregnancy such as uterus, placenta and fetus.

Age, sex and genetics are only part of the picture. Our lifestyle decisions will impact the BMR. Modifiable factors we can alter are:

- Lean body mass: Since muscle fibers are metabolically active even at rest increasing lean body mass (muscle) by being active and exercising will increase the BMR. Weight training is an effective way to increase BMR.

- Energy balance: The energy balance also impacts the BMR. Fasting or weight loss starts metabolic adaptations that increase the efficiency of the energy metabolism. This can mean a 10 - 20 % reduction when the body enters conservation mode during weight loss.

- Lifestyle: Stress increases nervous system activity and along with that the BMR slightly. Tobacco and caffeine also have a slight increasing impact on the BMR.

Studies determining the BMR in large populations came up with a formula that allows us to estimate the BMR for men and women. In average women need 0.9 kcal/kg/hour while men need 1 kcal/kg/hour. Keep in mind that the BMR can vary 25 - 30 %.

Physical activity can range widely and has two components. NEAT or non-exercise activity thermogenesis includes our everyday physical activity. Standing, getting up, walking around, climbing stairs, cleaning increase the energy expenditure. Even if we are sitting still on the sofa, watching our favorite show, we will fidget and contract muscles.

NEAT depends on how active we are during the day. Sedentary individuals spend only small amounts of energy on top of the BMR. This makes balancing energy intake and energy expenditure much more difficult especially in our energy dense food environment.

Exercise is the second component of the physical activity energy expenditure. This component can vary widely depending on the time spent exercising, intensity and type of exercise. The amount of muscles mass also plays a role in how much energy is expended during an exercise session. Larger muscles will use more energy for the same work.

Every time we eat hormones signal cells to synthesize enzymes and digestive juices. Many nutrients need ATP-dependent active transporters to pump the nutrients across cell membranes. Once all nutrients are metabolized and stored the metabolism returns to an equilibrium. Digestive enzymes and hormones are broken down. These postprandial processes require energy in form of ATP. This increase in energy expenditure is called the thermic effect of food or TEF.

The TEF is a relatively small component of the energy expenditure. Around 5 to 10 % of the energy intake is used to digest food and metabolize nutrients. The TEF depends of course on the amount of food eaten since more food requires more energy to digest. If you eat mixed meals yielding around 2000 kcal in a day, around 200 kcal would be used to digest and metabolize those meals.

The TEF also varies with food composition. Protein-rich foods require about 20 - 30 % of the energy intake, while carbohydrate-rich foods require 5 - 10 %. The least amount of TEF is required when fat-rich foods are eaten. Triglycerides do not need to be converted into other nutrients but can be efficiently stored in the adipose tissue right after absorption.

You might have read in social media that eating a high-protein diet will burn so much more calories. The TEF is a relatively small component of the energy expenditure. The impact of muscle mass on the BMR, energy spend on physical activity and the efficiency of the metabolism will outweigh the slight increase in TEF when more protein is eaten.

The smallest component of the total energy expenditure (TEE) is the cold-induced thermogenesis. This can include shivering, muscle tensing and fidgeting when temperatures drop and we are starting to get cold.

Humans also have special adipose tissue that produces rather heat than storing large amounts of energy.

This type of adipose tissue is called beige and brown adipose tissue. It looks brown (or beige) under the microscope because it contains many mitochondria.

Newborns have larger amounts of brown adipose tissue but as the infant grows it is turned into white, fat storing adipose tissue. Adults have only small amounts left.

Some white adipose tissue can be turned beige (increasing mitochondria) due to cold exposure and intense exercising.

People with more beige and brown adipose tissue maintain body weight easier. There seems to be a genetic component determining amounts of those heat producing adipose tissues.

2. Determining a Healthy Weight Is More Complex Than Stepping On a Scale

When we visit the physician's office we immediately are ushered to the scale. Our height and weight is then used to determine the BMI. While the determination of weight is necessary so the physician can estimate the dose for medications, the BMI is also used to gauge if we are at a healthy weight. You also might have heard that the BMI is not reliable, does not work. The question is if this is true, why do physicians still use the BMI and why didn't we come up with something better.

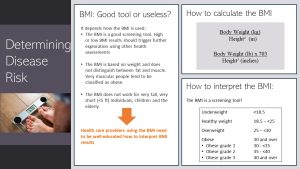

The BMI is a reasonable, quick tool to gauge disease risk for most people.

But, anybody using it needs to fully understand how to use the BMI properly. First, the BMI does not work for everybody. Healthcare providers should not use the BMI to determine disease risk for very short individuals (< 5 ft), very tall individuals, children and the elderly.

Second, the BMI is based on weight and height. This means that the BMI does not distinguish between fat and muscle mass. Very muscular people will end up with a high BMI not reflective of their health status, and might erroneously be classified as obese.

For everybody else—the majority of the US population—the BMI is a good and practical screening tool. Screening tool means that health risk should not be solely determined by the BMI result, but trigger a conversation about eating, exercise and other health behaviors followed by some lab tests.

The BMI is calculated by dividing the body weight in kilogram by the squared height. If you work with pounds and inches the body weight is divides by the squared height and then multiplied by 703.

How do you interpret the BMI? The BMI is categorized into four groups: Underweight (< 18.5), healthy weight (18.5 - 25), overweight (25 - 30) and obese (>30). The obesity category is then split into three grades. Grade 1 ranges from BMI 30 to 35 and grade 2 from 35 to 40. A BMI over 40 is considered obesity grade 3.

The healthy weight BMI is associated with the lowest risk for chronic diseases in adults until 65 years of age. The overweight BMI has a slightly increased risk but the risk seems to depend more on lifestyle and genetics. Risk is increased for the underweight and obese categories. The higher the obesity grade the higher the risk for developing chronic diseases.

Keep in mind that we are talking about risks. This means that it is more likely that people in the obesity category develop chronic diseases, but there will be people with a higher weight who will go through life healthy. On the other hand there are some people in the healthy weight category who are at an increased risk for chronic diseases.

A better way to determine the risk for chronic diseases is by body fat percent. Before we look into the methods to determine body fat we need to straighten out some terminology.

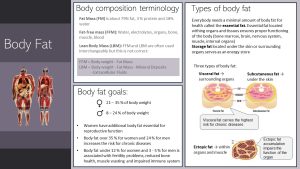

While the BMI sets the body weight in relationship to height it will not be able to tell us anything about the body's composition. The body composition describes the relationship of fat mass to fat-free mass or lean body mass.

- Fat mass is the amount of adipose tissue. Adipose tissue is 79 % fat , 3 % protein and 18 % water.

- If we subtract the fat mass from the body weight we will get fat-free mass. Fat-free mass includes muscle, organs, blood, electrolytes, bone and body water.

- When it comes to future health the relationship between muscle and fat gives us the best idea how healthy our body is. The best approximation is the lean body mass which includes muscle and organ tissue. Bone (mineral deposits) and extracellular fluids (blood and water outside of cells) are excluded.

There are also different kinds of fat mass. Everybody needs a minimum amount of fat to function properly. This is called the essential fat which is located within organs and tissues. The remaining fat is considered storge fat. It is located under the skin and around organs. Some storage fat is important to cushion and insulate our body and organs.

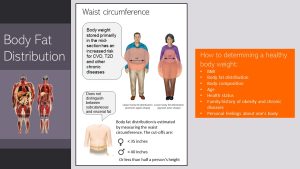

A different way to categorize fat mass is to differentiate it by location in the body.

- Subcutaneous fat is located under the skin

- Visceral fat is located in the body cavity surrounding the organs.

- Ectopic fat is fat within muscles and organs.

High amount of visceral fat is connected to an increased risk for chronic diseases such as T2D, CVD and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. If people have less visceral and more subcutaneous fat their risk is much lower.

As people gain weight and age they deposit more ectopic fat. While some ectopic fat is necessary for organ and muscle function, too much accumulation of ectopic fat impairs the function of the tissue. For example, accumulation of ectopic fat in the muscle reduces performance.

From studies looking into chronic disease risk we know that a body fat content of 21 - 35 % carries the lowest risk for women and for men that number is 8 - 24 %. You might have noticed that women have a higher healthy fat mass. Women need this additional fat mass for reproductive function.

Body fat under 12 % for women and under 3 - 5 % for men is associated with fertility issues, reduced bone health, muscle wasting and an impaired immune system.

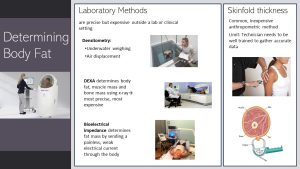

The best methods determining body fat require costly equipment more likely to be found in research laboratories. The devices are precise but expensive to buy and maintain.

Densitometry (underwater weighing and air displacement) determines the body volume. Mathematical formulas allow the researchers to calculate body fat bringing body volume in relationship to body weight.

DEXA (dual x-ray absorptiometry) is the most precise method and can determine not only fat mass but also lean body mass. Aside of research labs, you will see DEXA machines in hospitals to determine bone density.

Bioelectrical impedance (I explain how it works on the next slide) can be found in research labs. Less precise and less expensive devices can also be found in gyms.

The problem is that the devices determining body fat reliably and precisely are too expensive for physicians and not mobile enough for screening events.

A more practical and portable method are calipers measuring skinfold thickness. A technician pulls the skin and subcutaneous fat from the muscle usually on the upper arm, the scapula (flat bone on your upper back) and the hip. The measurements are entered into a formula yielding body fat percent. The issue with this method is that it will require a trained technician who understands how to precisely pull the skinfold. Otherwise, the result can include muscle overestimating the body fat or not enough subcutaneous fat underestimating body fat.

After understanding the methods for fat mass determination it becomes clear that percent fat mass is not a practical screening tool to determine chronic disease risk. That is the reason why we are still using the BMI.

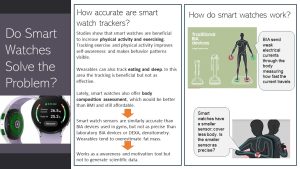

Lately, a new device is on the market that has the potential to replace the BMI over time: Smart watches using bioelectric impedance to determine fat mass.

BIA (bioelectrical impedance analysis) devices send a weak electrical current through the body. Since fat has a low water content the electrical current is transmitted slower than by muscle mass with a high water content. Based on the time the electrical current travels back to the device body composition is calculated. Keep in mind that the BIA devices calculate fat mass and fat-free mass, not lean mass.

Precise laboratory devices have large sensors sending the current through the entire body. Smart watches use a smaller sensor sending the current through the upper body.

The question is how precise those smart watches are. A few preliminary studies found that smart watches are similar to the larger gym BIA devices. These devices are reasonably precise for personal tracking of body composition over time. This can generate awareness and motivation. The precision is not sufficient for research though. Over time smart watches have the potential to replace the BMI.

Since we are on the topic of smart watches. Studies show that using smart watches to track daily activity increases awareness and motivation. People using these trackers increased physical activity by 60 %. Studies also show that tracking does not work as well for improving eating or sleep habits.

When we determine if weight is healthy or not, the BMI can scan populations for individual follow-up.

A better health indicator is body composition. In addition to body fat we also need to consider where the fat is located. Bodyweight located in the midsection is called central obesity. These individuals tend to have the appearance of an apple-shaped body. Central obesity carries a higher risk for chronic diseases than a pear-shaped body when adipose tissue is distributed around the hips and thighs. Increased subcutaneous fat carries a lower risk for chronic diseases than visceral fat in the stomach.

Body fat distribution can be determined by measuring the waist circumference. Physicians should follow up with further assessment if women have a waist circumference over 35 inches and men over 40 inches.

In summary, what a healthy body weight is can vary from person to person. Healthy weight has multiple contributing factors. BMI can be a starting point as well as body composition and body fat distribution. Those measurements should be followed up by a physical and nutritional health assessment, family history of obesity and chronic diseases, and personal feelings about one's body.

Ultimately, a healthy weight is a weight that

- supports optimal physical function

- reduces our risk for chronic diseases

- we feel happy about.

3. Weight Loss Is Possible, But the Maintenance Of the Lower Weight Is Extremely Difficult

Between 1999 and 2020 the prevalence of obesity rose from 30.5 % to 42 % of the US population. During the same time severe obesity rose from 4.7 to 9.2 %.

Despite the concerning rise in obesity and severe obesity, Americans try to lose weight. CDC data from 2018 show that 56 % of women and 42 % of men try to lose weight every year. The weight loss and weight management industry is flourishing and expected to grow from $ 224 billion in 2021 to $ 405 billion in 2030.

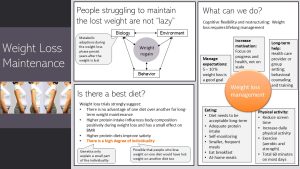

The reality of weight loss is frustrating. Only 20 % of people who lost about 10 % of their weight maintain the lower weight at the end of the year. Looking at long-term weight loss maintenance the reality is even more sobering with the majority of people slowly gaining the weight back or even exceeding the weight at the beginning of the weight loss journey.

Health care provider often chalk up this inability to maintain a healthy weight to a lack of discipline or just laziness. This is far from the physiological facts. During the next slides we will explore what happens during weight loss and maintenance of the lower weight.

Why Do So Many People Gain Weight?

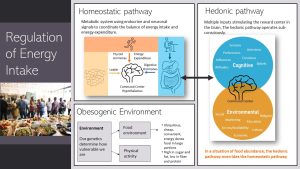

First let's explore why so many Americans gain weight in the first place. Energy balance is regulated by two systems.

The first system is metabolic, the homeostatic pathway. The center of the homeostatic system is the hypothalamus in the brain coordinating multiple inputs to increase or decrease the drive to eat:

- Endocrine signals from the gastrointestinal tract such as ghrelin secreted by the stomach signal hunger and satiation during a meal. Hours after the last meal the shrinking stomach triggers the secretion of the hormone ghrelin. The brain registers the increased ghrelin blood concentrations. We start feeling hungry. As the stomach fills and expands during a meal ghrelin secretion tapers off and satiation sets in.

- If we gain weight the growing adipose tissue increases the secretion of the hormone leptin. The hypothalamus detects those higher concentrations and reduces the drive to eat. If we lose the weight the opposite happens. Falling leptin concentrations increase the drive to eat.

- Increased energy expenditure due to physical activity or thyroid hormone secretion is registered as well and factored into the decision by the hypothalamus to increase or decrease the drive to eat.

If the energy balance was solely driven by the homeostatic pathway we would all effortlessly regulate our energy intake according to our energy balance. But, the regulation of the energy balance is complicated by the hedonic pathway.

The hedonic pathway has multiple cognitive and environmental inputs also registered by the hypothalamus in the brain. The problem is that the hedonic pathway operates subconsciously and we often do not even register how our environment drives our appetite and eating.

Hundred of years ago when food shortages altered with times of food abundance the hedonic pathway was a survival tool. When people entered a time of food abundance the hedonic pathway overrode the homeostatic pathway triggering weight gain. For example, the hedonic pathway drove overeating and energy storage during summer and fall so people had enough energy reserves during winter and early spring.

Today, the hedonic pathway is in constant overdrive negating the homeostatic pathway. We are living in a food environment marked by an abundance of cheap, convenient, energy-dense foods in large portions. Fast food chains, vending machines, fast, casual dining are available everywhere and tend to provide sweet, fatty and salty delicious food.

Daily physical activity is a thing of the past. We drive everywhere, spent our days sitting at a desk, communicating electronically. For every household or garden chore we have an electrical tool. Our spare time is spent relaxing, watching videos on our electronic devices.

How much we are effected by the obesogenic environment depends on our genes and our social and physical environment. For most Americans this means a slow weight gain from childhood to middle adulthood. More and more children are already obese and develop chronic diseases in their teen years.

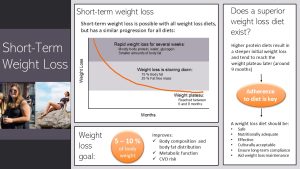

Short-Term Weight Loss Is Possible Independent of the Diet

Short-term weight loss is possible independent of the chosen weight loss diet. The way weight loss progresses is just not what many people expect and social media influencers promise.

Weight loss has three phases:

- Fast weight loss: During the first weeks to months rapid weight loss takes place if the energy balance is negative. The majority of this weight loss comes from the loss of lean mass (protein), water and glycogen. Some body fat is lost.

- Slowing of the weight loss: After the initial rapid weight loss phase the metabolism adjusts. Weight loss slows down. During this phase the weight loss is 75 % fat, but still 25 % body protein.

- Weight plateau: Around month 6 to 9 the weight loss ceases. It becomes hard to lose additional weight.

We see this weight loss progression for all diets. Higher protein diets and the keto diet result in a steeper initial weight loss. The plateau tends to be reached later, around 9 months. But, at the end of the first year studies show little difference between weight loss diets.

The second misconception is the weight loss goal. When people are asked how much weight they would like to lose they feel 20 - 40 % would be good. For most people this goal is not realistic. Studies show that a weight loss of 5 - 10 % of the starting body weight is sufficient to improve body composition, fat distribution, metabolic health and to reduce CVD risk. If the weight loss of 5 - 10 % goes well and the weight loss is maintained, people can still aim higher later.

The question is now what weight loss diet is recommended? We know that adherence to the diet is key to see successful weight loss. Therefore, it is important how well somebody can stick to the eating pattern.

A weight loss diet should be safe—appropriate for existing health conditions—and nutritionally adequate. Extreme diets eliminating several food groups such as the keto diet are nutritionally inadequate long-term.

Of course, the diet should be effective, which means losing weight without losing too much body protein. That's where the higher protein eating patterns come in. A higher protein intake combined with exercise can retain more lean mass resulting in less BMR reduction during weight loss.

The diet needs to be culturally acceptable. For example salad and lean protein eating is not acceptable to all cultural groups. Lastly, the diet should not be a diet but a healthy eating pattern that can be followed for the rest of the life.

This makes it clear that extreme diets such as the keto diet are not a good choice no matter what influencers claim. A meta-analysis analyzing 13 weight loss studies using the keto diet showed that many study participants dropped out of the study, between 13 and 84 % of participants. When the carbohydrate intake was measured it showed that in 9 of the 13 studies the carbohydrate intake was too high to trigger ketosis as the study progressed. The other three studies didn't measure the carbohydrate intake.

The Key to Metabolic Health Is Not the Short-term Weight Loss, But the Maintenance of the Lost Weight

Social media will tout short-term weight loss. You know now that over the course of 6 to 9 months weight loss is slowing down until a weight loss plateau is reached. It's even worse when we look at long-term weight loss. The plateau will turn into a slow weight regain for most people. Many end up with a higher weight than they started out with. This finding is independent for the type of diet and applies even if people are physically active (graph above).

Why are weight loss attempts so futile?

1. Loss of lean mass: During weight loss people not only lose fat mass but also lean mass. The amount of lean mass is, as you learned above, a predictor for the RMR. As lean mass is lost the RMR slightly declines.

2. Metabolic adaptions: The metabolism will try to hold on to as much weight as possible. A hundred years ago when food insecurity altered with times of food abundance this was a survival mechanism to get for example through the winter or crop failure.

Therefore metabolic adaptions are triggered by the weight loss. The total energy expenditure (TEE) will decline in average—this varies from person to person—20 - 30 kcal per day for each kilogram lost. Most of the reduction comes from a declining RMR. RMR declines not only due to the loss of lean mass but declining leptin triggers a reduction in thyroid hormone secretion. This decline in thyroid hormones will make the metabolism more effective. Less wasteful heat energy is produced. In addition, the sympathetic nervous system is calmed and the parasympathetic nervous system takes over. More energy is conserved.

3. Drive to eat: On the other side of the energy balance the drive to eat increases. This is due to endocrine regulations. The adipose tissue secretes less leptin acting on the brain to increase the drive to eat. Gastrointestinal hormones, for example increased ghrelin secretion, leads to a more pronounced feeling of hunger between meals and reduced satiation during a meal. Some studies show that the appetite increases around 100 kcal/d per lost kilogram of body weight.

Reduced TEE would make it necessary to eat even less to maintain the lost weight or lose more weight. Increased drive to eat will make it difficult to maintain the lower energy intake.

4. Psychology: In addition, the slowing weight loss impacts motivation. The cost of weight loss becomes higher compared to the benefit. In studies exploring weight loss using low-carb or keto diets we clearly see that carbohydrate intake increasing over time and the eating slowly reverting back to old habits.

Even worse, studies show that the reduced RMR, often 300 to 500 kcal lower than expected by calculation based on body weight, will persist for years after the weight is regained. A large reduction of RMR will lead to further weight gain.

If people go from one weight loss to weight regain to another weight loss, the RMR keeps decreasing. Weight loss and the maintenance of the lost weight become increasingly more difficult.

This is where exercise comes in. Exercise will increase the TEE and grow muscles increasing the RMR. Exercising 60 minutes on most days including a strength training program can compensate for the reduced energy expenditure and slow down weight regain (see graph above).

The Hard Truth: Weight Loss Is Possible, Maintenance Of the Lower Weight Is Extremely Difficult

It is important to clearly state: People struggling to lose weight are not lazy and they do not lack discipline. Their metabolism works hard against the weight loss.

Weight regain happens between the individual's

- Biology: Extend of metabolic adaptations, genetics

- Obesogenic environment: Do we have financial means, education, skills and social support to avoid marketing, temptations and convenience?

- Behavior: Are we eating when stressed or bored, overeat when ample amounts of tasty food is available?

We need to change how we think about weight loss. First, weight loss will require life-long management. Weight loss is not just about the initial weight loss phase but the focus must be on the long-term weight loss management. Keep in mind that the obesogenic environment makes weight loss management difficult by stimulating the hedonic pathway. The drive to eat and searching out food is enhanced after weight loss.

Other factors impacting weight loss success are emerging from studies:

- Mange your expectations: Wile most people expect a weight loss of 20 - 40 %—social media suggests even more drastic goals— an initial weight loss goal of 5 - 10% is a great start. People should also be educated that the initial weight loss is achievable but that long-term weight management is difficult. We should expect some ups and downs in weight. Maintaining the weight within a narrower range should be seen as much a success as losing the weight in the first place.

- Increase motivation: As we have already discussed motivation will decline once weight loss is slowing or the weight loss plateau is reached. Motivation can still be increased by focusing on the overall progress and health improvements instead of the scale.

- Long-term support: Especially during the first year—ideally longer—people will need support by health care professionals in form of behavioral counseling and training as well as a support group.

When it comes to dietary interventions they need to be acceptable in the long-term. People should not expect to follow a weight loss diet for six months and then go back to their pre-weight loss eating habits. This means that extreme diets such as the keto diet or a low-carb diets can kick-start weight loss, but are not well suited for long-term weight loss and weight maintenance. These diets might be used as a starter diet but over the first six months eating needs to transition into a healthy, acceptable eating pattern that can be maintained life-long.

Healthy eating means meals cooked from fresh ingredients. The basis of the meal should be vegetables, fruits, whole grains and legumes. Then moderate portions of meat, poultry, fish, and dairy are added. Sweet and fried foods should be eaten only occasionally.

Higher protein intake (eat protein, do not drink it) seem to improve satiety. Keep in mind that legumes (beans, lentils, chickpeas) are nutrient dense and healthy protein sources. High protein does not mean automatically high meat.

High fiber intake also promotes satiety. Studies show that higher carbohydrate eating patterns from natural plant foods provide plenty of fiber and promote weight loss and better weight maintenance. This is in contrast to eating ultra-processed food which are low in fiber and nutrients.

Self-monitoring leading to better self-awareness is a good tool. Together with behavioral tools such as having a contingency plan for situation when overeating is likely, people will be better equipped to navigate our obesogenic environment. Given the high caloric, unhealthy, tasty and convenient food system, people managing their weight successfully tend to enjoy an occasional eating-out but cook the majority of their meals at home using fresh ingredients and eat smaller, frequent meals.

Overall, there is a high degree of individuality—genetics only explain a small part—and people need to work out, hopefully with the help of a professional, what works for them.

In addition, life needs to be restructured to implement other health behaviors. Sedentary time (screen time) should be reduced and replaced with physical activity. Regular exercise, both aerobic and strength training, will not trigger weight loss by itself, but helps to maintain lost weight and increases metabolic health. For example, increasing muscle mass will increase the BMR making up for some of the TEE reductions. In total people on a weight loss and maintenance journey should make space for 60 minutes of physical activity on most days.

4. Orthorexia: When Healthy Eating Becomes An Obsession

Monitoring your eating and eating a specific, restrictive diet has it's risk. Over the last decades a new eating disorder has emerged: Orthorexia. So far orthorexia is not recognized by the DSM-5, the standard for classification of mental disorders used by mental health professionals, because orthorexia is so new and not researched enough to be included.

What is it? Usually orthorexia starts out with good intentions of eating a healthier diet. At one point—we don't know exactly what triggers it—healthy eating turns into an obsession. The current suspects are the social media environment micromanaging eating and an existing tendency for restrictive eating.

The compulsive checking of ingredient lists and constant concerns that food might damage one's health has social and mental health consequences. Daily quality of life and social interactions decline. The person isolates more and more and mental health declines.

When food groups are eliminated and only a narrow range of foods are eaten, the person with orthorexia is at risk for nutrient deficiencies and malnutrition. The risk for anxiety and depression and other eating disorders increases.

Keep in mind there is a fine line between being passionate about healthy eating and being obsessed with it. On the right side of the infographic above, you will find a list of warning signs. If you suspect you or a friend and family members struggle with orthorexia contact UNL CAPS. or another counseling service if you are not an UNL students. A good start might be here.

The primary energy carrying molecule in the cell sometimes called energy currency of the cell

After a meal

Type-2 Diabetes

Cardiovascular disease

Signaling to other tissues and organs

The parasympathetic nervous system predominates in quiet “rest and digest” conditions while the sympathetic nervous system drives the “fight or flight” response in stressful situations. The main purpose of the PNS is to conserve energy to be used later and to regulate bodily functions like digestion and urination (NIH.gov).

Feedback/Errata

8 Responses to Energy Balance