16 Growth and Development During the First Year of Life

Sabine Zempleni and Sydney Christensen

The first two to five years of a child’s life are a huge window of opportunity for setting up a healthy life. Choices parents are making during this time not only allow the child to grow to their full potential, but set up the metabolism, educate the immune system, determine taste preferences, and develop the child’s eating pattern. These choices will make it easier or more difficult for the child to live a healthy life later on.

My parents’ generation was much more relaxed about it. You brought your baby home and fed the baby with the recommended amount of baby formula. During the 1950s, 60s and 70s it was thought that formula was better and more convenient than breast milk. Few women nursed their babies. Next, parents started feeding food from baby jars and transitioned the baby to the food the family ate. If the baby grew well and was kind of chubby, you were doing a good job as a parent. Once the child ate at the table, the child needed to eat what was served and clear the plate.

Today, things seem much more complicated. Scientifically, we know much more about the factors that allow newborns to grow to their full potential metabolically. We have started to understand the amazing ways nature reacts to environmental stimulants by developing metabolism, immune system, and eating habits that are adjusted to the environment the infant is living in. We also have learned that nature is misinterpreting the modern Western living stimulants. From a scientific standpoint things have become more complicated and new parents tend to feel this pressure.

You will learn:

- Growth charts are used to track length, weight, and head circumference development

- One goal of several: Determine adequacy of nutrition.

- Growth chart basics

- Failure to thrive

- Body composition changes

- The maturation of the gastrointestinal tract is necessary for the transition to solid food at six months.

- During the first four months only breastmilk or formula should be fed due to the immature renal system.

- At six months, the infant starts the transition process to family meals.

- Waning feeding reflexes and motor development enable the infant to transition to spoon feeding

- Circular chewing requires teething and the cessation of all feeding reflexes

Growth Charts Are Used to Track Length, Weight, and Head Circumference Development

Adequacy of Nutrition

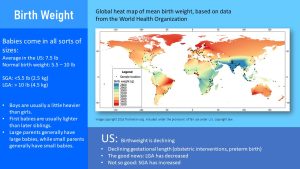

Newborns come in all sizes. A term infant is born between 37 and 42 week. Medically we distinguish between early term (37 to 38 weeks), full term (39 to 40 weeks) and late term (41 to 42 weeks). You can imagine that depending on when infants are born they can range in size quite a bit.

In addition, genetic factors and weight status of the mother determine the size of a newborn as well. Newborn boys are usually heavier than newborn girls, first babies tend to be smaller than their siblings, and large parents have generally larger newborns than smaller parents.

It is not surprising that birthweight can range. The average newborn in the US weighs 7.5 pounds but a normal birthweight can range from 5.5 to 10 pounds.

Once the infants are born they shift from hemotrophic nutrition to oral nutrition. During the first four to six months of life infants are fed solely breastmilk or formula. The question is, given the range of newborn size, how much milk should an infant have each day? Shouldn’t a larger infant need more milk than a smaller infant?

It becomes even more complicated when the mother nurses her infant. When a mother nurses the baby latches onto the nipple and the baby drinks breast milk until it is full. This makes it difficult to track how much milk the baby drank. How do we know that the mother produces sufficient amounts of milk? Can an infant be overfed? With breastmilk? Formula? Some mothers may rely on crying to act as a hunger cue, but there may be other culprits such as a wet diaper, gas, or an ear infection.

Since determining the amount of milk needed to enable optimal growth is too complicated, determining the adequacy of nutrition is done a different way: Tracking the growth of the infant.

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends seven well-baby visits during the first year. During those visits, the pediatrician checks the infant’s health and whether or not the infant is meeting developmental milestones. The nurse will also measure the weight, length, and head circumference of the infant and track those numbers on a growth chart.

Growth Chart Basics

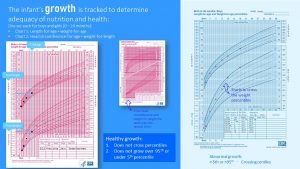

From birth to 24 months the health care provider will use a growth charts to track the weight, length, weight-for-length and head circumference development. Those infant growth charts are based on growth data from thousands of breastfed infants and separated into a male and female chart.

Once the child reaches age two a second growth chart is used to track growth development until age 18. The second set of growth charts, one for males and one for females, tracks weight, height and BMI for age. A weight for stature chart is also used.

Every time a child visits the pediatrician either for a check-up or sickness, their anthropometric data are taken and entered into the growth chart. This allows the pediatrician to track the growth.

Tracking on a growth chart involves finding the estimated age spot on the x-axis and entering the measurements. The chart has percentile lines ranging from 0 to 100. There are various increments including 2, 5, 10, 25, 50, 75, 90, 95, and 98.These percentiles stem from studies measuring thousands of healthy infants.

An infant growing on the 25th percentile is comparable or larger than 25% of the infants the chart is based on. In short, by plotting the infants measurements the pediatrician compares how the child is growing compared to other healthy infants.

Babies come in all sorts of shapes and sizes from the petite baby to a long, thin baby, to an average length, and chubby babies. Adequate growth is assumed if:

- The infants maintain growth along a percentile (line) established within the first month after birth. The infants growth can fluctuate somewhat, but should not cross percentiles.

- Infant growth should be between the 5th and 95th percentile. Infants growing in the extremes of the growth chart need to be closely monitored for developmental issues.

If an infant starts going off track—this is usually first seen in the weight development followed later by the length development—the pediatrician needs to investigate. Reasons could be an underlying health condition, insufficient breast milk, late introduction of solids, or a generally inadequate nutrition. Growth charts can be helpful in identifying these problems early.

At birth infants are charted on a growth chart and are placed into one of three categories based on their weight: small-for-gestational age (SGA), large-for-gestational age (LGA), or appropriate-for-gestational age (AGA). SGA infants have a birth weight below the 10th percentile, while LGA infants have a birth weight above the 90th percentile. SGA and LGA newborns will usually grow into their genetically determined percentile during the first month.

Adjusted Gestational Age:

Premature infants cannot just be plotted by their postnatal, chronological age. Age calculation needs to be adjusted by gestation. Subtract infant’s gestational age at birth in weeks from 40 weeks (term infant). Subtract that number from the infant’s current age. A infant born at 30 weeks would have an adjustment of 10 weeks (40 – 30). At the 4 months (16 week) checkup the measurements would be plotted against an age of 6 weeks (16 – 10).

Failure to Thrive

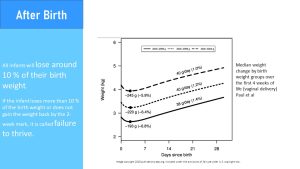

Right after birth, a newborn will lose about 10% of their body weight. This weight loss is physiological and mostly water, specifically extracellular water. If newborns lose more than 10% of their body weight or do not gain the weight back by the 2 week mark, it is called failure to thrive and will require tests.

Failure to thrive is generally described as inadequate physical growth diagnosed by observation of growth over time using standard growth charts. There is no absolute definition, nor is there a standardized tool to diagnose it. It may be organic (caused by a disease or disorder) or inorganic (not caused by an identifiable disease or disorder). Growth chart percentile jumps of 2 or more often indicate an issue.

Interventions often focus on increasing calories and proteins by supplementing breastmilk or using a more concentrated formula. As the infant begins to eat solid foods, the caregiver should opt for nutrient dense and fortified foods. It is also important to consider other risk factors for inorganic failure to thrive such as poverty, poor feeding practices, and excessive fussiness. It may be more difficult for caregivers to correct failure to thrive if these factors persist.

Growth Velocity and Body Composition Changes Change After Birth

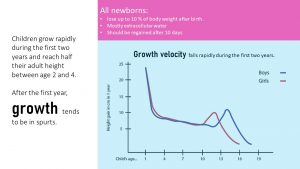

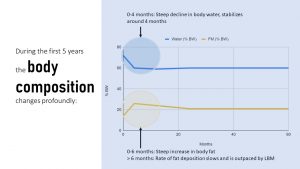

After birth, extra-uterine growth sets in at an incredible growth rate which is why infants require more calories per pound than any other age group. In general, infants should double their birth weight by 4-6 months and triple it by 12 months. Their length should double by 12 months. The growth velocity will sharply decrease throughout the first two years and their growth velocity will slow (see graph above.)

After about one year, the fast growth will end, and toddlers will start growing in spurts. Interestingly, those growth spurts are influenced by the seasons. Children grow more in the spring and early summer. This is often surprising to their parents since the child will not eat as much. Children are generally able to regulate their nutrient intake well if offered healthy food and left to decide how much they will eat. For the parents, this can cause anxiety since some children will go from eating next to nothing for days to eating ferociously everything in sight. We will talk about this later in more detail.

After birth, the body composition changes as well. Body water declines steeply from 70 – 83 % to 55 – 60% at 6 months. At the same time body fat increases reaching a peak around 6 months. Once the baby starts moving around, the chubby baby starts to slowly become slimmer and lean body mass increases.

We can easily see those rapid growth changes during the first year, but organ systems are going through rapid development as well.

The Maturation of the Gastrointestinal Tract is Necessary For the Transition to Solid Foods at Six Months

When we think about the function of the gastrointestinal system, anatomy, digestive fluids, and enzymes come to mind. For optimal function several other components need to be considered too: GI motility, barrier function, and gut microbiome.

Anatomical development: The anatomical differentiation of the fetal gut is usually completed within 20 weeks of gestation. This means that the major components—mouth, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, large intestine, rectum, and anus—are in place as well as the layers and functional cells of the long gastrointestinal passage. During the last trimester, the increase in the intestinal length and expansion of the surface area including villi and microvilli development takes place.

GI Motility: The gastrointestinal passage is not a shaped, inanimate hose food is slipping through. Instead, the compartments of the GI tract actively move the food (later called chyme in the stomach or bolus after leaving the stomach) forward from compartment to compartment. Within each compartment the bolus is thoroughly mixed. This active transporting and mixing is called GI motility.

GI motility includes the wavelike muscle contractions that move the food or intestine content through the esophagus and intestines forward, strong contractions of the stomach mix the chyme, and segmentation— moving the small intestine content back and forth. In addition, paced stomach emptying ensures that not too many nutrients reach the small intestine at once. As you can imagine, the coordination of these muscle contractions is complicated.

Peristalsis, the forward movement, is functional at 29 – 30 weeks of gestation. This means the mechanism is ready at birth of a full term infant, but many premature infants (born before week 30) need to be fed parenterally because their GI tract is not functional yet. Coordinated sucking and swallowing develops between week 32 to 34. Term babies have a strong suck-and-swallow reflex and are ready to go. In fact, once sucking and swallowing is matured enough during pregnancy the fetus swallows about 450 ml of amniotic fluid per day.

Other parts of the GI motility do not fully develop until birth, and some infants are still developing good coordination of GI motility after they are born. It is thought that this is the reason for the feared colic in young infants.

Digestion: While the ability to produce digestive juices is developed in the third trimester—lactase activity, for example, is detectable at 34 weeks gestation—enzyme activity is low at birth. Lactase activity at week 34 is only at 30% of the level at birth. All other important enzymes to digest milk are very limited right at birth. This includes limited pancreatic lipase and bile acids for lipid digestion, and limited lactase and amylase for carbohydrate digestion.

The first feeding after birth triggers a digestive growth spurt in the first 24 hours of birth. This is the reason why the small amount of breast milk the mother produces at this point is sufficient.

Barrier Function: At birth, the small intestine is leaky. This allows larger immunoglobulins from the breast milk to pass through between the enterocytes into the blood stream. During the first days of life, gut closure—the rapid reduction of epithelial permeability—takes place.

This is only part of the barrier function of the gut. In addition to having a leak-proof gut epithelium, the exposure to environmental bacteria stimulates the development of the gut microbiome, which in turn, stimulates the immune system. Together gut microbiome, gut epithelium, and immune system in the gut form a barrier against pathogens during the first months of life (more details in chapter 15 The Road to a Healthy Gut Microbiome).

Gut Microbiome: The GI tract of the fetus is almost sterile. When the fetus passes through the birth canal the maternal vaginal microbiome is transferred to the newborn. Together, with environmental bacteria and skin bacteria from people holding and handling the newborn, commensal bacteria start to cultivate on all body surfaces including the GI tract. The further progression of the microbiome cultivation is determined by the type of milk fed.

While I listed those GI functions individually keep in mind that normal gastrointestinal function relies on integrated maturation of absorptive, secretory, and motor function. Delay in any of those developments will result in disturbed gastrointestinal function. This can manifest in vomiting, abdominal distention, colic, and constipation.

During the First Four Months Only Breastmilk or Formula Should Be Fed Due to the Immature Renal System

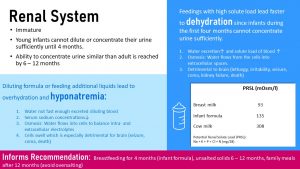

At birth, the renal system of the newborn is still immature and needs to undergo maturation. The main problem is that the newborn infant cannot concentrate or dilute urine. The maximal urinary concentration in the neonatal period is less than 700 mOsm/kg, but reaches adult values of 1200 mOsm/kg by 6 to 12 months of life.

This means that the newborn needs to be fed a solution that has the right amount of electrolytes and a moderate amount of protein. Only breastmilk and formula fit the bill. An indicator about how much solutes a food produces during metabolism is the potential renal solute load or PRSL for short. The PRSL is calculated from the sodium, potassium, phosphorus, chloride, and nitrogen content of the milk. Breastmilk has a very low PRSL of 93 mOsm/l, formula is a little higher but still within the capability of newborn kidneys (135 mOsm/l). Feeding undiluted cows milk to a newborn would be detrimental with a PRSL of 308 mOsm/l.

After birth, the kidneys keep developing continuously and the ability to concentrate urine like an adult is reached by the age of 6 – 12 months. This maturation process informs dietary recommendations.

During the first four months the infant should only be fed breastmilk or formula. Even water, diluted juice, or tea is not advised. After four months, the kidney function has progressed enough that solids can be slowly introduced. At this point some water on a hot day is fine as well.

Until the end of the first year, solid food should not be salted to keep the amount of sodium in need for excretion in the urine low.

After the first year, the child can participate in normal family meals, but parents should take care not to offer overly salty or processed foods.

Dehydration and Hyponatremia

What exactly would happen if parents decide to feed, on one hand cows milk or concentrated formula, or on the other hand additional water or diluted formula? Keep in mind that this is not hypothetical. Parents might use more powder because they feel that their infant is not growing fast enough or dilute formula because money is running out at the end of the month and they cannot afford more formula.

Dehydration: If the infant is fed concentrated formula, cows milk, or cereal is added to the bottle—usually to help the infant sleep through the night—high amounts of sodium, potassium, phosphorus, chloride, and nitrogen circulate the blood stream.

While glucose and triglycerides are completely metabolized to O2 and CO2, protein produces nitrogen that needs to be excreted. If an infant is fed high amounts of protein, the surplus is used for energy purposes. In the process, amino acids are deaminated and the carbon skeleton enters the energy metabolism. The nitrogen is incorporated into urea. The electrolytes and the excessive urea need to be excreted.

Since the kidneys are not able to concentrate the urine, large amounts of water need to be excreted along with the excessive amounts of solutes. This leads to dehydration even if the infant receives predominantly liquid foods. The water intake is lower than the large amounts of urine excreted.

As the dehydration progresses, the solute load of the blood increases as blood plasma declines. Osmosis causes the water to shift from cells into the blood circulation. Cells shrink and that impacts the brain.

Initially, the infant will sleep more and seem irritable. Mouth and lips will be dry. The soft spot on the skull (fontanelle) sinks in. The infant needs to be rehydrated immediately because seizures, coma, and kidney failure threaten the life of the infant.

Hyponatremia: If parents diluted formula or feed supplemental liquids, hyponatremia—too little sodium in the blood—develops. Since the infant cannot excrete the excessive water fast enough, blood is diluted and blood electrolyte concentrations fall. Since intra-and extracellular electrolyte concentrations need to be balanced water is diffusing into the cells (osmosis). Along with all other cells, brain cells swell which increases brain pressure. Headache, nausea, vomiting, fatigue, along with muscle cramps are the first identifiable symptoms. If the hyponatremia progresses seizures, coma, and death follows.

To prevent these problems, it is essential that parents and caregivers only feed breastmilk and formula mixed according to the instruction during the first four months.

At Six Month the Infant Starts the Transition Process to Family Meals

At four to six months, breastmilk alone will not be enough to supply sufficient energy and nutrients for the growing child. Several developments need to take place to first enable the ability to eat from a spoon and ultimately to chew solid foods and self-feed.

Feeding reflexes during the first four months: Infants are born with reflexes that prime them for breastfeeding. These feeding reflexes include the rooting reflex and the suck-and-swallow reflex. If an infants cheek is touched, for example, by a nipple of the breast or bottle the infant turns the head towards it. Once the nipple touches the inside of the mouth the suck-and-swallow reflex sets in and the infant automatically takes in milk and swallows.

Rooting reflex and suck/swallow reflex:

Tongue thrust reflex:

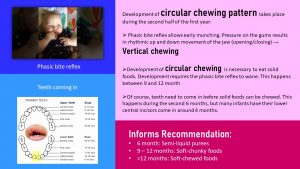

Phasic bite reflex:

In addition, the extrusion (tongue thrust) and gag reflex prevents the infant from choking on solid or semi-solid foods, or non-nutritive items that make it into the mouth of the infant. If the tongue is touched by a semisolid or solid object, the tongue will push forward, and hopefully, push the object out of the mouth. If the object bypasses the extrusion reflex, the gag reflex makes sure it is not swallowed.

With those feeding reflexes in place the infant will be a natural when it comes to feeding from the breast (or bottle).

Fine-motor skills: Developing fine-motor skills are first visible when a bottle fed infant “helps” feeding by putting a hand on the bottle during the second or third month. Keep in mind that becoming a helper does not mean that the infant is ready for a solid spoon. This transitions into the ability to hold the bottle around the six month mark. At the same time the infant has the ability to drink from a sippy cup, which should be encouraged to start the transition away from the bottle. Bottle feeding should stop with the first birthday.

During the 5th or 6th month the infant has developed a pincer grasp that will allow them to pick up a small piece of melt-in-the-mouth food, such as a (sugar-free) cheerio, and place it in the mouth.

These various changes allow the infant to ease into complementary feedings, which involves the introduction of semi-liquid solid foods and small pieces of soft food.

Development of Eating From a Spoon and Chewing Requires Fading of Early Feeding Reflexes and Teething

Eating From a Spoon Skills

The feeding reflexes make drinking from the breast or a bottle during the first six months automatic. No special skills needed.

Eating from a spoon is different. The infant needs to develop fine motor skills and some of the early feeding reflexes need to wane. If parents offer a spoon with semi-liquid food to a 3-month old infant, the touching of the lips will start a sucking motion. Since the spoon is solid the tongue thrust reflex (or gag reflex depending how far the spoon is stuck into the mouth) will set in and the tongue will push against the spoon. This makes more of a mess than feeding the infant.

Therefore, the suck and swallow, tongue thrust, and gag reflex need to wane to allow the spoon into the mouth. The phasic bite reflex will remain for a while longer. This reflex allows to transport a bolus from the front to the back of the mouth. This reflex is initially essential to remove pureed food from the spoon and transport it to the back of the mouth and then swallow.

Progression to Chewing Soft Food

After a pincer grasp develops, infants can pick up small melt-in-the-mouth foods such as an infant cracker or cheerios—both without added sugar—and place it into their mouth. When the food touches the gums, the phasic bite reflex kicks in, a vertical chewing motion is started. The same motion can be seen when the infant is fed purees with a spoon. This early munching practices chewing, transporting food to the back of the mouth, and swallowing. This works for soft foods—first chunky, then in pieces—but is not really effective to chew more solid foods.

Transitioning to the family table with chewy foods requires the development of a circular chewing pattern. Try to chew a piece of chicken with a vertical motion, no lateral motion allowed. Not possible. Between the 9th and 12th month the phasic bite reflex vanishes allowing for a combined vertical and lateral motion. The child will still need to practice a lot to graduate to a piece of steak, but the stage is set.

Of course, in addition to the vanishing reflexes the infant needs to grow some teeth. The first set of teeth coming in are the lower central incisors giving the infant that cute look. Before those teeth become useful—instead of chomping down while breastfeeding—several more teeth need to come in—especially the molars. This development stretches all through the second year and part of the third. This lack of a full set of molars is the reason while the toddler will still have a tough time chewing harder food and need to be supplied with smaller pieces of food.

Overall, the continuous, progressive development during the first year will allow the infant to develop eating skills:

Age |

Infant Eats |

Developmental Milestones |

| 0 – 6 months

|

Exclusively breastmilk or formula

|

Feeding reflexes in place

|

| 6 – 9 months

|

Breastmilk/formula, semi liquid foods, melt-in-the-mouth food pieces

|

Rooting, suck and swallow reflex vanishes, phasic bit reflex in place, pincer grasp develops

|

| 9 – 12 months

|

Breastmilk/formula + soft-chunky transitioning to soft pieces of food

|

Vertical chewing due to phasic bite reflex develops into circular chewing when reflex vanishes Teeth coming in

|

Editors: Sydney Christensen, Gabi Ziegler

NUTR251 Contributors:

- Spring 2020: Taylor Donner, Kalen Codr , Tim Gillespie, Grace Neville, Kaye Hutchison, Eugene Baraka, Madison Korthas, Caleb Licking

- Fall 2020: Shalin Bhakta, Miles Judson, Ken Zhao, Clare Caraghar, Felicity Bowers, Kaitlyn Higgins, Morgan McCain, Collin Mahler

The exchange of nutritients between the maternal and fetal blood circulations

Percentiles are the most commonly used clinical indicator to assess the size and growth patterns of individual children in the United States. Percentiles rank the position of an individual by indicating what percent of the reference population the individual would equal or exceed. For example, on the weight-for-age growth charts, a 5-year-old girl whose weight is at the 25th percentile, weighs the same or more than 25 percent of the reference population of 5-year-old girls, and weighs less than 75 percent of the 5-year-old girls in the reference population (CDC).

Osmosis is the movement of water molecules from a solution with a low solute load to a solution with a high solute load through a cell's demi-permeable membrane. That way the concentrations between two compartments are equalized.

Feedback/Errata