6 Metabolic Health Can Be Improved But It Is Hard

Sabine Zempleni

Image copyright 2025 Getty Images. included under the provision of fair use under the U.S. copyright law

So far we established that the NCDs hypertension, CVD and T2D are multifactorial diseases that develop over a long time. Interestingly, they all have one metabolic origin in common: Metabolically unhealthy obesity, specifically low-grade chronic inflammation. These three diseases are also interconnected.

Drugs are available to treat and manage T2D and CVD successfully. Hypertension due to obesity is often drug resistant though. The best treatment for all three diseases—and several other diseases and condition that are due to metabolically unhealthy obesity—would be a healthy lifestyle and weight loss. Losing weight will reduce the chronic inflammation and slow the disease progression. After weight loss is achieved insulin resistance, blood pressure and blood lipids will improve. Easy solution? Frustratingly, no.

According to CDC data 17 % of US Americans are on a special diet on any given day (CDC, 2015 – 2018). This includes weight loss diets and diets treating chronic diseases. Many people go from one unsuccessful weight loss diet to the next.

Social media influencers tell us that weight loss is difficult until you follow their plan. Their diet, exercise program, supplement or lifestyle will make weight loss a breeze. Post-weight loss pictures of toned followers serve as testimonials.

Working through this chapter you will understand that weight loss and the maintenance of the lower weight is extremely difficult. Admitting this will change how we think about people struggling to lose weight. Rethinking weight loss, modifying weight loss expectations and redefining success can be a good first step.

As usual, recall what you already know. If not, review:

The first piece of information we need to understand is that weight loss can only take place if the body is in a negative energy balance, taking in less energy than the body expends. This means either eating less or increasing physical activity. This sounds on first look simple but it is not. Our metabolism can make it very hard to take in less energy by increasing hunger and appetite.

Hunger is the biological feedback loop that indicates that it’s time to eat. Everybody knows what being hungry feels: Growling stomach and a feeling of weakness. Keep in mind that the intensity of hunger feelings is very individual. Some people feel hunger more intensely and have a hard time functioning when hungry. Others can forget to eat all day because they do not feel hunger too intensely. Hunger is driven by the hormone ghrelin.

Appetite is the willingness or motivation to eat. You probably experienced it: We can be hungry but don’t feel like eating. Appetite is complex and multifaceted with many inputs. Biological inputs are gastrointestinal hormones, leptin signaling energy reserves, and circulating nutrients and their metabolites. These signals are read by the hypothalamus and combined with psychosocial inputs. Psychosocial inputs can stem from our environment (for example walking by a vending machine, driving by a fast food place, meeting with friends, food ads), learned eating behaviors, our food culture and many more. Appetite can be specific to a food or types of foods.

The current recommendations for weight loss combine moderate caloric reduction (~500 kcal) with increased physical activity and behavior changes. The dietary pattern should be nutrient dense reducing high caloric processed foods while increasing fruits, vegetables, whole grains and legumes. This results in a decrease of refined and simple carbohydrates. Protein intake should be adequate or might be increased to a moderate level.

These dietary changes should be supported by increased daily physical activity and a well-rounded exercise program for 60 minutes on most days of the week. Both aerobic exercise and strength training are recommended.

In addition behavior modification is recommended.

You will find more details about the energy balance in the Foundational Nutrition and Metabolism section. Reviewing will help you gain a better understanding and will solidify the science.

You Will Learn:

- Eat less, exercise more? It is not that simple

- Weight loss is possible, but we need to rethink it.

- The initial weight loss target should be 5 – 10 %.

- Weight loss starts out rapid, followed by a slow-down until a weight loss plateau is reached.

- Substantial weight loss is possible, but maintaining the lower weight is hard.

- The weight loss plateau will turn into slow weight gain.

- The metabolism puts up a fight to maintain adipose tissue.

- Metabolic adaptations due to weight loss persist long-term.

- People on a weight loss journey need help.

- Behavioral interventions help weight loss and attenuate weight regain.

- Bariatric surgery can help jump-start weight loss in severely obese patients. Maintenance is difficult as well.

- Semaglutide leads to dramatic weight loss but it lasts only as long as the drug is taken.

- What else can be done to improve metabolic health?

Eat Less, Exercise More? It is Not That Simple

Overweight and obesity are contributed to an imbalance between energy intake and energy expenditure. This is a scientific fact.

This scientific fact is often mixed up with a much more complicated question. Why do so many people have problems maintaining a healthy weight, and why are people with overweight or obesity not able to lose excess weight.

For a long time the paradigm Eat less, exercise more was the standard recommendation for maintaining a healthy body weight. For some people this worked but for others it was a source of major frustration. The key to understanding why this approach to weight loss doesn’t work is that there are other factors interfering in the energy balance. While we try to lose weight our metabolism keeps moving the goal posts farther away.

To understand what happens during weight loss it is important to understand how energy intake is regulated.

There are the two major physiological pathways regulating food intake.

One is the homeostatic pathway that regulates the homeostasis between energy intake and expenditure. This pathway increases the motivation to eat when energy stores are depleted or increases satiety when sufficient amounts of foods were eaten. The homeostatic pathway can also increase or decrease the efficiency of the energy metabolism.

The command center of the homeostatic pathway is the brain and there are four major inputs.

The first input is the secretion of digestive hormones. After food is digested and the stomach is empty the stomach starts to secret ghrelin. Once we eat and the stomach fills up pressure receptors read the degree of expansion. Ghrelin secretion subsides. The hypothalamus reads the amount of ghrelin circulating in the blood stream. High ghrelin stimulates feelings of hunger while declining ghrelin increases the feeling of satiation.

While food is digested and moves along the digestive tract, other digestive hormones are secreted by the stomach and small intestine. Primarily, these hormones coordinate digestion but also prepare the metabolism for the incoming nutrients. The hormones enter the blood circulation and message the status of the digestion to the brain to suppress appetite depending on macronutrient composition and food amount. This is the reason why we usually do not have a drive to eat right after a meal.

The second input is nutrient sensing. As absorbed nutrients are cleared from the blood circulation certain nutrients and their metabolites are tracked by the brain. This information is combined with other inputs to increase or decrease appetite.

The third input of the homeostatic pathway is the signaling from existing energy stores. Leptin is one of the hormones involved here. Again, the hypothalamus in the brain monitors leptin blood concentrations. A decrease of leptin secretion with shrinking adipose tissue increases the drive to eat. Increasing leptin secretion with growing adipose tissue tends to reduce appetite.

Interestingly, the drive to eat during an energy shortage is much more potent than the down regulation when energy becomes abundant again. As a result gaining weight is much easier than losing weight.

The fourth input is the energy expenditure. Even when we are at rest our metabolism will require energy. Increasing energy expenditure for example due to exercise is read and appetite increased.

Newer research shows that the drive to physical activity and exercise is not completely determined by our behavior. The hypothalamus can trigger spontaneous physical activity (SPA) which increases energy expenditure. SPA is increased during a positive energy balance (leptin ↑) and reduced during a negative energy balance (ghrelin ↑).

Eating does not just provide energy and nutrients but is also a pleasurable experience. This is where the second pathway, the reward-based regulation or hedonic pathway, comes in. The inputs for the hedonic pathway vary and are complex. These cues mostly stimulate the pleasure center of our brain.

During times of abundant food supply the hedonic pathway will override the homeostatic pathway by increasing the desire to eat palatable foods. Today’s food environment supports this physiological overeating by providing ubiquitous and abundant amounts of very tasty food.

Cues stimulating the hedonic pathway can be cognitive. Sensory cues such as seeing, smelling and tasting delicious food increases food consumption. Habitual eating behavior and our social environment also alter food consumption. Some individuals have excessively restricted eating behaviors while others eat uninhibited. Emotions ranging from being bored to happy to sad to stressed can influence how much we eat. How much those psychosocial factors impact eating decisions varies widely between individuals.

In a past long gone, most people were exposed to food only during meal times when they actively sought out food. Today, our environment impacts our eating behavior. External cues such as the constant presence of food or food advertising trigger more and frequent eating. Food availability, geographic and economic factors determine what food we eat. Many social interactions are connected to food. Nutritional and non-nutritional factors such as food composition, meal size, plate or serving sizes alter our eating behavior. For example people eat more when served a larger portion.

The hedonic regulation tends to override the homeostatic energy regulation in today’s obesogenic food environment. As a consequence overeating is common. In addition, once weight is gained metabolic changes to the homeostatic pathway makes it easier to gain weight and harder to lose it.

This said, we all react differently to the food environment. Eating behavior develops during childhood and early adulthood based on our food and eating experience which is determined by our social environment, cultural experience and education.

In part this explains why the old eat less, exercise more weight loss recommendation fails.

Does Food Addiction Exist?

For starters, the term “addiction” is inappropriate in this context. Addiction is a debilitating, chronic, relapsing brain disease. Overeating is not.

Eating is a pleasant experience and naturally triggers the pleasure center in our brain releasing dopamine and opioids. As part of the hedonic pathway this feel good response is a survival mechanism. Eat a lot when palatable food is available to prepare for times of food shortages. True substance addiction taps into the same system but destroys feedback loops and regulation.

At this point scientists are fairly sure that humans don’t get truly addicted to specific foods. Animal experiments showed an overshooting response of the hedonic pathway to high sugar and fat intake. For humans the results are less clear and need to be researched in more depth.

Weight Loss Is Possible, But We Need To Rethink It

Before we even look at the weight loss science, you should wrap your head around what weight loss even means. Take a minute and think about what picture comes to mind when you think about weight loss. Thanks to social media browsing, most of us will probably conjure up a picture like the one below. Today, weight loss is often defined as reaching a toned, thin body for women and a body with visible, larger muscles for men.

Most people will not reach this ideal because their genes and life circumstances will not allow them to. Others will reach this ideal briefly, but will return over the next years back to their old weight. As a consequence, people on a social media fueled weight loss journey will end up frustrated. Until, they recover and come across the next big promise starting the cycle again.

The first step for health care providers and people looking for weight loss alike is to understand how weight loss takes place and set realistic expectations.

The Big Picture: What Should Weight Loss Look Like?

Realistic weight loss should start with a target to lose 5 – 10 % of the baseline weight. If somebody starts out with a weight of 200 pounds the target would be a 10 to 20 pound weight loss. Of course, once the weight loss target is reached and maintained a new target can be set.

Many studies have shown that the 5 – 10 % weight loss is connected with major health improvements. Body fat declines and body composition improves. Less adipose tissue reduces inflammation and cardiometabolic risk factors improve. Overall metabolic function improves, for example insulin resistance and glucose homeostasis.

Secondly, the focus should be on metabolic health and not on looks. One major barrier to weight loss and maintenance of the lower weight is the waning motivation if not enough weight is lost or when some weight is regained. Focusing on metabolic and health improvements can keep fueling motivation.

Many people start restrictive diets, such as Keto or vegan, and experience a good weight loss. Over time the restrictive diet becomes increasingly difficult to adhere to and people shift slowly back to their old eating habits. Studies looking at long-term weight loss using the keto diet show that the study participants tend to incrementally increase their carbohydrate intake, if they stay in the study. Drop-out rates are extremely high. Anywhere between 13 and 84 % of study participants quit depending on one review (Bueno et al 2013).

Instead of restrictive diets a healthy, individualized eating pattern should be identified. That way the person is more likely to stick with it long-term. Weight can be lost on any eating pattern as long as caloric intake is reduced.

Ideally, a dietitian will work with the patient and design an individualized weight loss plan. The desired caloric deficit depends on the degree of obesity, previous weight loss and existing co-morbidities. Most importantly a discussion should take place what lifestyle changes are possible based on the ability to commit as well as financial, social and physical restraints.

Overall, a weight loss plan should be based on a healthy eating pattern with caloric restriction supported by exercise and behavioral therapy.

Increasing physical activity and exercise alone are not as effective as caloric restriction to induce weight loss in most people. In carefully controlled experiments increasing energy expenditure with exercise shows effectiveness but study results in real life look very differently. This is surprising but studies show that the metabolism will start to compensate for the additional energy expenditure (see homeostatic pathway above). 1 in 2 individuals experience enough metabolic compensation so weight loss will become impossible by solely exercising. This said, physical activity and exercise are a crucial part of weight loss and even more during weight management.

Lastly, we should keep in mind that most people have learned unhealthy eating behaviors over a lifetime. These behaviors will work against their efforts to improve eating habits. Behavioral therapy and active follow-up by health care providers have been shown to aid weight loss and manage weight after the desired weight is lost.

What Should You Expect When Losing Weight?

Many people expect that they start a weight loss journey by choosing an effective diet and adding an exercise program. If they stick for example to a high-protein diet and exercise program sufficiently, weight loss will be rapid until the desired weight is reached permanently.

This is not how weight loss works.

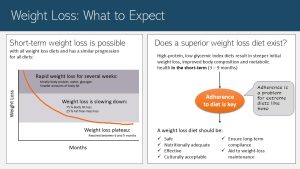

Weight loss has three phases:

- Rapid weight loss: During the first weeks weight loss will be rapid for all dietary patterns. We should keep in mind though that this rapid weight loss will be mostly body protein, water and glucose stores (glycogen). When we reduce caloric intake severely the metabolism is forced to use up glucose stores. After those stores are empty some body protein is used to replenish glucose blood levels since the brain has not adapted to using fat as an energy source yet. Glycogen stores and body protein contain a good amount of water that is lost in the process. During this initial phase only smaller amounts of body fat are lost.

- After a few weeks the metabolism adjusts and weight loss is slowing down. During this second phase 75 % of the lost weight comes from body fat and 25 % from fat-free mass (protein and water). Losing weight, especially metabolically active lean mass, means that less energy is needed to maintain less body. At the same time the metabolism starts counter measures to use energy more effectively. A larger caloric deficit would be needed to keep the weight loss going.

- After 6 to 9 month a weight loss plateau is reached and weight loss stagnates even if adherence to the weight loss plan is high. At this point additional weight loss will become difficult.

Experiencing slowing weight loss or even weight loss stagnation impacts motivation. The feeling of personal failure sets in and adherence declines.

Substantial weight loss is possible but we should expect slowing of weight loss until the plateau is reached. The question is now if there is a superior diet that maximizes weight loss.

Every time somebody cites a study that proves superior weight loss, you should have a look at how long the study lasted. Many studies are conducted researching only the weight loss phase. These studies show that short-term weight loss can be achieved with any diet as long as caloric intake is reduced. High protein, low-glycemic index diets and the keto diet (low- or very-low carbohydrate diets) show the steepest initial weight loss.

Does that mean that low-carbohydrate diets are superior? The key to successful weight loss is adherence to the diet. As I already mentioned keto diets are so extreme that many people cannot adhere long-term. Lower-carbohydrate, higher protein diets might work because they can be adjusted. Protein can come from lean meat and fish or nutrient-rich plant-based proteins such as legumes. A shift to lower glycemic whole grains will allow for carbohydrate consumption and make the eating pattern easier to tolerate.

Overall, the eating pattern should be individualized. It should be safe (consider co-morbidities and age) and nutritionally adequate. Studies show that larger weight loss at the beginning of the weight loss journey predicts better results. Therefore, the diet should be effective. The eating pattern should also be culturally and long-term acceptable. Even more important is that the eating pattern can be used long-term for the maintenance of the lower weight.

This means that the best weight loss diet is the one we can stick to.

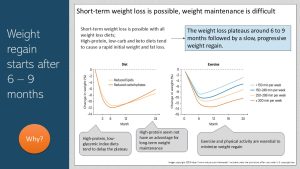

Substantial Weight Loss Is Possible, But Maintaining the Lower Weight Is Hard

Social media influencer and sometimes physicians promote high-protein and keto diets because studies demonstrated that weight loss is accelerated and therefore thought to be superior. Again, you should always ask how long this study lasted because more often than not the study misses the entire picture. Weight loss and maintenance phase should always be considered together.

The Weight Loss Plateau Will Turn Into Slow Weight Gain

It would be great if people lose weight, experience the slowing of the weight loss and reach the plateau. If they would stay at the plateau weight and have lost 5 – 10 % of the baseline weight they would experience major health benefits. The problem is that the weight loss plateau is not the end of the weight loss journey for most people.

Even if we stick to the new diet and eating habits, which is difficult enough, we will experience a slow weight regain. This weight regain is fueled by adaptations to our metabolism.

If adherence wanes in addition to the metabolic adaptations the weight regain will be even faster. As adherence wanes individuals on low-carb diets tend to start eating more carbohydrates. Individuals on low fat, high carbohydrate diets tend to eat more fat and less carbohydrates. Habitual eating habits that caused the weight gain in the first place sneak back into the dietary pattern. The faster the adherence wanes the faster the weight is regained. In average, people regain weight at a rate of 1 – 2 kg per year. This regain is faster right after the weight loss and then slows down somewhat.

The graphs above summarize weight loss and regain studies by diet and exercise. The graph on the left shows that reduced carbohydrate diets and low fat diets show the same weight loss and regain pattern. Only small differences are noticeable.

High protein, low-glycemic index diets tend to delay the plateau. Studies looking solely at protein intake find that adequate protein intake is necessary to improve satiety after a meal, but high protein diets seem not to have an advantage. Reducing energy density (low-fat diet) seem to slow down the regain.

Exercise and physical activity are essential to improve metabolic health—regular exercise reduces chronic inflammation—but weight regain takes place as well. Weight regain is slowed though depending on the amount of exercise. Here is where the 60 minutes of exercise and physical activity on most days stems from: 60 minutes x 5 days = 300 minutes per week.

Are all macro-nutrient calories equal?

A calorie is a calorie independent of the macro-nutrient delivering it. But, protein, carbohydrates and fats impact satiety differently and therefore contribute to the regulation of the energy intake differently.

Protein induces longer satiety and a sufficient protein intake seems to help weight loss and maintenance. We just need to keep in mind that protein does not equal meat. Plant-based proteins such as legumes are healthy and work as well.

Digestible carbohydrates such as sugars and starches trigger a more short-term satiety. Fiber is a different story though. It increases food volume and decreases energy density. This leads to increased satiety after a meal. If the fiber is combined with a high water content—for example in fruits and vegetables—the effect is even greater.

For fat the situation is paradoxical. High amounts of dietary fats induce a strong satiety response—her comes the catch—once the fat reaches the intestine. On the other hand people who eat a high fat diet tend to overeat energy. Scientists think the reason for this paradox is that the satiety response is so delayed that the palatability of fatty foods initially stimulate over-consumption of energy. Since a gram of fat has over double the kcals (9 kcal/g) than carbohydrates or protein (4 kcal/g) overeating high-fat foods is easy.

The Metabolism Puts Up a Fight To Maintain Adipose Tissue

It was always clear that weight loss maintenance is much more difficult than weight loss. Behavioral explanations seemed to explain this. Most people feel that they have “finished weight loss” once they reach a desired weight. Weight loss behaviors such as regular exercise, self-monitoring, contingency plans feel tedious and cease. In addition, weight loss comes with a feeling of success such as smaller clothing sizes, completing daily tasks easier, better health, and lots of compliments. During the weight loss phase calendars are adapted and families support the person on a weight loss journey. Weight maintenance means going back to normal. No successes, no compliments for maintaining the lower weight, a family who wants to eat “normal” again.

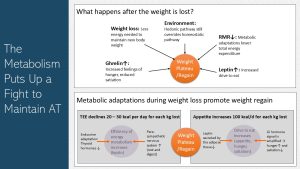

Over the last decades scientists also started to understand that weight loss alters metabolic regulation of eating profoundly. Many motivated people are still gaining weight because nature is working against them.

We already addressed two factors leading to a decline in RMR during weight loss:

- Body size impacts RMR. As weight is lost energy needs decline slightly.

- Another factor determining RMR is the amount of lean mass. About 25 % of the lost weight is metabolically active lean mass which means energy needs are further reduced.

This would mean that the caloric intake would need to be continuously reduced as more weight is lost. This would be an relatively easy adaptation. Much more difficult is to counter that the metabolism is now putting up a fight and keeps moving the goal posts.

An empty stomach during weight loss is secreting more ghrelin and the receptors in the brain are becoming more sensitive. During a meal ghrelin blood levels return slower to normal. In consequence a person losing weight is hungrier and it will take more food to feel satiated.

As the adipose tissue shrinks less leptin is secreted. This has major consequences:

- Thyroid hormones decline and the parasympathetic nervous system is more active. This results in a more efficient energy metabolism. Usually only 25 % of the produced energy is converted into ATP. The rest dissipates as heat energy. During weight loss lower thyroid hormone blood levels ensure that less heat energy is wasted. The drive to move also is downregulated.

- The parasympathetic nervous system runs in the background and we are not aware of it. If the parasympathetic nervous system is more active we are calmer and have less drive to move. Less energy is expended.

Increasing efficiency and reducing the amount of energy expended total energy expenditure is around 20 to 30 kcal lower for each kilo gram (2.2 pounds) body weight lost. If a person’s baseline weight is 200 pounds and 10 % or 20 bounds are lost, energy expenditure would be 200 to 300 kcal lower.

In addition, less leptin and more ghrelin increase hunger and appetite, and reduce satiation. It is estimated that this is worth 100 kcal of increased appetite for each kilogram bodyweight lost. We need to keep in mind that studies don’t show a large increased energy intake after weight loss, but scientists don’t count it out because many people underestimate their food intake if asked to record it. At a minimum, if the drive to eat is this large during and after weight loss it would make it super difficult to stick to the new eating habits.

Keep in mind that the food environment hasn’t changed. We are still living in a food environment of affluence. The reduced leptin does not just increase the drive to eat but also triggers a preference for those sugary, fatty palatable foods. The metabolic adaptations will make it even more difficult to avoid the temptations such as the regular doughnuts at work and the string of fast food places on the way home.

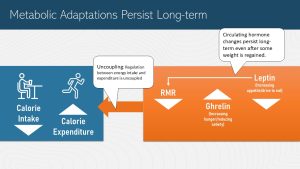

Metabolic Adaptations Persist Long-Term

It get’s even more frustrating. The metabolic adaptations that were triggered by weight loss will persist long-term.

In its simplest form weight regulation is a feedback loop between the brain and the body periphery. The periphery signals the status of energy stores. When energy stores decrease the brain increases the efficiency of energy use, triggers a preference for high-energy palatable foods, and decreases satiety.

If more energy is spent than consumed the feedback loop triggers hunger and eating more.

Interestingly, the feedback loop is also buffering occasional over- and undereating. If we overeat on some days our energy metabolism becomes less efficient and burns more calories. The drive to move increases and we burn slightly more energy. If we undereat we become less energy efficient and move less. These adaptations are so subtle that we don’t notice but they help maintain body weight. This is called the settling point.

After weight loss we would expect that the body settles into the new, lower weight. That doesn’t happen though. After weight loss the regulation of the energy intake and expenditure is uncoupled. The new energy metabolism has one job: To get back to the higher weight. In times past when food abundance was often followed by food shortages this was a survival mechanism.

A study following participants of the Biggest Loser demonstrates this. The scientists looked at the RMR of participants after 6 years. To their surprise the researchers found that the RMR was in average 500 kcal/d lower than expected by body weight and composition. There was a large individual variation between study subjects though ranging from a 292 to a 706 kcal/d deficit.

With our understanding of the metabolic adaptations during weight loss, it is not a surprise that so many US Americans struggle to lose weight and maintain a lower weight.

People On a Weight Loss Journey Need Help

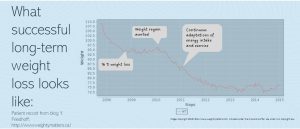

Losing weight looks different for each individual person. However, if individuals want to succeed then it is crucial to acknowledge that it won’t be a steep steady decline in weight all the time. There will be periods of slow weight loss while for other periods there might be a weight plateau. Vacations, holiday seasons, birthday parties, or phases of stress might even trigger some regain of weight. The patient record below shows an example of successful weight loss and maintenance. This is what real long-term weight loss looks like.

What Successful Weight Loss Looks Like

The chart depicts the weight loss journey of a patient participating in a holistic weight loss program at Dr. Friedhoff’s clinic. You can clearly see the slowing weight loss and weight loss plateau. The weight loss plateau was reached at 16 % weight loss, later than expected and the lower weight was maintained for a good amount of time.

During the weight loss plateau you can also see the ups and downs the patient went through. After two years a second weight loss target was set. I’m sure that this additional weight loss came with more lifestyle changes such as increased exercise or more intense exercise.

At the end of the chart the patient maintained the weight loss for seven year. We need to keep in mind though that the lifestyle that let to the weight loss will need to be maintained or weight is regained.

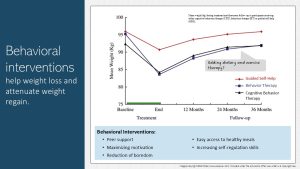

Behavioral Interventions Help Weight Loss And Attenuate Weight Gain

What helped this patient above to be that successful?

Some patients with co=morbidities receive care from a physician and a dietitian during the weight loss phase. Maybe a support group helped the patient to keep up motivation. When the weight loss target is reached the thinking is that the patient has finished weight loss and care tends to be discontinued. We need to rethink this approach.

The research shows that ongoing behavioral interventions and continuing visits with a team of health care providers makes it more likely that the lower weight is maintained or that the weight increase is very slow. The study results depicted in the infographic above show that while the patients regained weight, the weight gain was slower if the patient received ongoing behavioral or cognitive therapy.

The goal of those cognitive and behavioral interventions are to maintain high motivation, enhance self-regulation skills and a reduction of boredom. Peer support is helpful.

In addition, it is important to make healthy meals accessible. Cooking healthy meals after a long, exhausting day will require huge amounts of motivation if fast food options are easy and fast. Since our food environment will not change anytime soon increasing food storage, meal preparation and cooking skills might increase the numbers of healthy meals eaten.

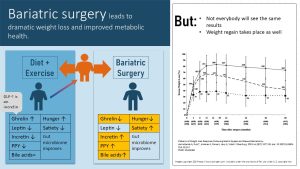

Bariatric Surgery Can Help Jump-Start Weight Loss in Severely Obese Patients. Maintenance is Difficult As Well.

Bariatric surgery leads to a dramatic weight loss and is becoming a common treatment option for obesity especially in severely obese individuals with chronic diseases.

During bariatric surgery part of the stomach is either tied off or removed creating a small stomach pocket. Other bariatric surgery techniques bypass the stomach and directs food directly into the duodenum.

The weight loss can vary individually though as the graph on the right above shows.

Not everybody has success. Some patients re-gain weight slowly after the initial weight drop. After bariatric surgery patients need to learn how to eat small portions of food. Otherwise the stomach and intestines expand over time allowing the patient to eat more and absorb more calories.

While bariatric surgery was invented to help severely obese patients to lose weight rapidly and hopefully maintain some of the weight loss, studies tracking those patients after surgery had a surprise in store. Bariatric surgery induces beneficial changes in hunger and satiety regulation as well as beneficial effects on glucose metabolism and insulin sensitivity before weight is lost.

Especially after the type of bariatric surgery that bypasses most of the stomach, ghrelin secretion decreases and PYY, another hunger hormone, increases. Less ghrelin and PYY means less hunger and better satiety after a meal.

The incretin GLP-1, secreted by the pancreas and gut during digestion, is involved in the blood glucose management. Increased GLP-1 results in more effective insulin secretion and better blood glucose regulation. This is thought to be the key to the immediate improvements of T2D after the surgery.

Bile acids are essential to emulsify fat during digestion but they also provide feedback about incoming fat to the metabolism and modify the gut microbiome. Increased secretion of bile acids is discussed to have positive metabolic effects.

Overall, bariatric surgery is an good option to jump start weight loss and metabolic improvements for people with metabolically obesity. Since bariatric surgery is an invasive surgery it will have the same dangers as any surgery. Obese individuals are especially vulnerable to complications during surgery and often have delayed wound healing. The benefits need to outweigh the dangers.

Bariatric surgery will not magically fix all problems. The patient will still need to learn healthy eating, portion control and an active lifestyle. Otherwise, weight is slowly gained back.

Problem behaviors influencing appetite and unhealthy eating decisions are still kicking in after the novelty wears off. Behavioral intervention can help improve adherence and motivation.

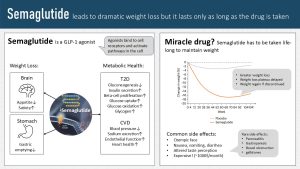

Semaglutide Leads To Dramatic Weight Loss But It Lasts Only As Long As the Drug Is Taken

Semaglutide, better known as Ozempic, is the newest hope for easy and successful weight loss. Hollywood celebrities started the trend, influencers promote it as a miracle drug. Is Ozempic a miracle solving the weight loss problem or not?

Semaglutide is a GLP-1 agonist. Since semaglutide is a protein it needs to be injected and then binds to cell receptors usually occupied by the incretin GLP-1. When people become obese their gastrointestinal tract produces less GLP-1. Less GLP-1 impairs the removal of glucose from the blood circulation after a meal. Semaglutide was designed to improve glucose tolerance in people with T2D.

Semaglutide had a surprising side effect in those T2D patients: Reduced appetite and rapid weight loss. This started the off-label use (drugs have to be FDA approved and semaglutide was only approved for T2D) and a drug shortage. Additional research triggered by the surprise weight loss finding showed that semaglutide acts on the appetite regulation in the brain suppressing the drive to eat. The drug also slows down stomach emptying resulting in prolonged satiety after a meal.

This is the main effect people on semaglutide are reporting. The reduced appetite and increased satiety makes healthy eating easy. Weight loss is rapid and the weight loss plateau is reached later.

In addition metabolic health is significantly improved. The liver produced less glucose, more glucose is taken up into cells and oxidized. In people with T2D insulin secretion increases. On the CVD side endothelial function and heart health improves. Blood pressure is lowered.

Sounds very much like a miracle drug until you look at the side effects.

You might have heard about Ozempic face. Since the weight loss is so rapid, weight is not just lost in the midsection but also in the face. A thinning face will give the impression of rapid aging. This is more a cosmetic side effects. Others are more concerning.

Semaglutide can have life-threatening side effects, but those are very, very rare. Many people experience the mild side effects such as nausea, vomiting and diarrhea after larger meals. In addition, over time the initial happiness about the reduce appetite can turn into frustration. Some people miss enjoying food and have an altered taste perception.

This is a problem because as soon as people stop taking semaglutide the appetite returns and weight is regained. Patients would need to stay on semaglutide indefinitely to maintain the lower weight.

But, semaglutide is an expensive drug. A monthly supply would cost around 1000 $. Since the prescription of semaglutide is still off-label physicians have to make a good case for insurances to cover the cost. After successful weight loss insurances usually stop covering the cost and patients often cannot afford it out of pocket.

Since the drug is so new we also don’t have good data what effects long-term suppression of appetite could have.

Just like bariatric surgery semaglutide has pros and cons. Before starting semaglutide patients should have a thorough conversation with their physician.

What Else Can Be Done To Improve Metabolic Health?

Bariatric surgery and semaglutide are able to counter biology to a certain degree but are not perfect solutions for everybody. The question is if there are other strategies to improve metabolic health if weight loss is not successful.

Regular exercise is a promising contender. Regular exercise reduces chronic inflammation, enables better glucose uptake into cells and improves artery health. In addition, strength training increases muscle mass and with that RMR increases.

Lately though evidence emerged that exercising might positively regulate the energy regulation feedback loop. The research is still brand new but here are a few ideas that are proposed:

- People who exercise during weight loss have better adherence to dietary interventions. It is not clear why.

- Exercising affects appetite, food choices and overall intake.

- Exercise results in a more inefficient energy metabolism—the muscle converts more energy into heat—increasing energy expenditure.

Sounds amazing? These study results will be very frustrating for 50% of the American population. The additional beneficial effects of exercise are only seen in so-called exercise responders. Here is the frustrating part: Responders are more likely to be male.

Research is also ongoing to identify compounds that could improve metabolic health in people with obesity. For example, we know that vegetables, fruits, whole grains and legumes contain phytonutrients that are anti-inflammatory. Diets rich in plant-based foods such as the Mediterranean reduce chronic inflammation and therefore improve metabolic health.

Research into the benefits of individual phytonutrients and other bioactives are in early stages. These studies are looking more at high, pharmacological doses, amounts that food consumption cannot supply. The idea is to identify compounds that can be developed into anti-inflammatory drugs.

Other nutrients such as indigestible carbohydrates, soluble fibers and oligosaccharide, and phytonutrients modulate the gut microbiome—another major source of chronic inflammation—in a positive way. This is again an argument to eat a healthy diet rich in whole grains, legumes, vegetables and fruit.

Overall, considering that weight loss and maintenance is often unsuccessful it might be wiser to focus on improving metabolic health by starting a well-rounded exercise program and eating a plant-heavy mixed diet.

Interested In More Information?

Fothergill E, Guo J, Howard L, et al. Persistent metabolic adaptation 6 years after “The Biggest Loser” competition. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2016;24(8):1612-1619. doi:10.1002/oby.21538

MacLean PS, Wing RR, Davidson T, et al. NIH working group report: Innovative research to improve maintenance of weight loss. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2015;23(1):7-15. doi:10.1002/oby.20967

Flanagan EW, Spann R, Berry SE, et al. New insights in the mechanisms of weight-loss maintenance: Summary from a Pennington symposium. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2023;31(12):2895-2908. doi:10.1002/oby.23905

Editors: Nicole Legler, Gabi Ziegler

NUTR251 Contributors:

- Spring 2020: Allison Aden, Grace Neville, Grant Young, Caroline Leibel, Kristine Krager, Dylan Fruhling, Kalen Codr, Rawan AL Jabri, Kristine Krager, Amelia Johnson

- Fall 2020: Morgan McCain, Megan Appelt, Miles Judson

Non-communicble diseases, a group of diseases not caused by an acute infection.

body protein such as muscles and organs

Carbohydrates that increase blood glucose only slowly

Resting metabolic rate

The parasympathetic nervous system predominates in quiet “rest and digest” conditions while the sympathetic nervous system drives the “fight or flight” response in stressful situations. The main purpose of the PNS is to conserve energy to be used later and to regulate bodily functions like digestion and urination (NIH.gov).

An agonist is a drug that binds to a receptor and produces a similar metabolic response than the signaling molecule by the body. An antagonist is a drug that binds to the receptor and stops the receptor from producing a response.

Feedback/Errata