32 Obesity, Sarcopenia, and Frailty Prevent Longevity

Sabine Zempleni and Eric Hanzel

During the last decades of life, time will start to take its toll on our bodies, and things just won’t function like they used to. A combination of reduced strength, mobility, and cognition is the inevitable fate that many of us must acquiesce to.

The degree to which we experience physical decline varies depending on the lifestyle choices we make. Much like the longevity of a car is dependent upon routine oil changes, maintenance check-ups, and tire rotations, the human body demands routine exercise, cognitive activities, and healthy choices. If your goal is to become a centenarian and have a high quality of life to the end, then these changes need to start in young to middle adulthood.

Previous chapters point to an association between high BMI and increased risk to develop chronic diseases earlier in life, so maintaining a healthy weight and lean body mass is the obvious goal. You already learned that obesity and chronic diseases accelerate aging, but in this chapter, you will learn that obesity can also contribute to early frailty.

You may be surprised to know that our trusty BMI—an easy predictor of mortality in many adults—becomes nearly obsolete as our aging bodies start to relinquish the muscle, bone, and fat mass that has carried us to old age. In this chapter, we hope to draw attention to the growing ambiguity of BMI with age, to talk about frailty as a major driver of low life quality in high age, and to provide strategies to keep us healthy and functioning as long as possible.

You Will Learn:

1.The BMI is not a good predictor for mortality, but a sudden drop in weight is:

- After age 65, body composition changes and the need for energy reserves change how the BMI should be interpreted.

- After age 65, the BMI should be used to monitor weight development.

- Sudden weight loss is the strongest predictor for mortality.

2. The development of frailty impacts quality of life and longevity:

- Sarcopenia is the driving force for frailty.

- The development and progression of frailty is a dynamic process.

- Progressing frailty is connected to an array of geriatric symptoms.

3. Frailty prevention and intervention strategies include diet and exercise:

- Dietary prevention and intervention aim to reduce severe obesity, sudden weight loss, and inflammation. A Mediterranean-style diet is recommended.

- Frail individuals should start an appropriate exercise program. This includes light resistance, balance, flexibility, and endurance training.

The BMI Is Not a Good Predictor for Mortality, But a Sudden Drop In Weight Is

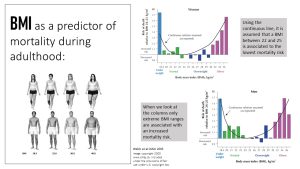

You are probably familiar with the black line in the graph above from other nutrition courses; it represents our assumption of the connection between BMI and risk for premature death. According to the black line, the ideal BMI seems to be anywhere between a BMI of 22 and 25. Once the BMI is outside of this “ideal” BMI, the risk of dying prematurely is supposed to increases in a U-shaped way. As always, keep in mind that there are population groups the BMI does not apply to, such as very short, very tall, and very muscular adults.

During the last decades, this understanding changed. Scientists re-examined the data behind this U-shaped mortality curve and realized that the analysis was hasty. A renewed analysis indicated that for the entire normal and overweight BMI range, mortality is not necessarily increased. Chronic diseases—morbidity—is still more likely in the overweight category, but a healthy lifestyle and plenty of physical activity and exercise can go a long way. However, once we get into the obesity or underweight BMI range, the risk for premature death increases exponentially.

In addition, a small part of our overweight population can be considered metabolically healthy. They show no signs of high blood pressure, elevated blood lipids, and insulin resistance. In contrast some people in the normal weight category carry excess adipose tissue in the body cavity and have decreased metabolic health.

During young and middle adulthood, the BMI is a good screener for the development of chronic diseases. Practically though we should not immediately jump to conclusions if the BMI is over 25. A high or low BMI should always lead to further discussions about lifestyle habits, and not just the recommendation “to lose some weight.”

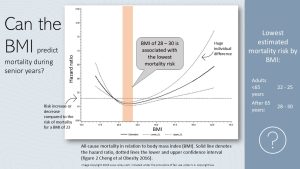

Once scientists started looking specifically at the data for adults over 65 years, the results were surprising. When you look at the graph above the horizontal line is the mortality risk (hazard) when the BMI increases or decreases compared to a BMI of 23 (the assumed “healthiest” BMI). If the hazard ratio is above 1 the risk for mortality is larger, if the hazard ratio is below one the risk is lower compared to a BMI of 23. The nadir of the solid line indicates the estimated lowest risk. Seniors with a BMI of 28-30 tend to have the lowest mortality risk.

Another interesting result: The thin lines—confidence intervals—above and below the average hazard for death depict how certain we are about that average. The wider the two thin lines are apart the less confident we are. When you look at the confidence lines you see that the higher the weight, the wider the range. This means that there is a large variation in the data. Some obese seniors are not at an increased risk of dying early, while others have a much higher risk due to their weight. Confusing? You are not alone.

Diving deeper in the weight research for aging adults a few trends emerge:

- The changing body composition of seniors

- The fact that adipose tissue has a purpose as an energy reserve.

The BMI and Age-Related Body Composition Changes

You were introduced to this issue during the pregnancy chapter: Pregnant women see a physiological shift in body composition—more fat mass and body water—which makes the BMI obsolete for them.

Seniors also have a physiological shift to more fat mass, including a shift from subcutaneous to visceral and intramuscular fat stores. Additionally, bone mass declines, and lean mass tends to decline after age 75. These changes in body composition makes the BMI harder to interpret.

In old age, a BMI between 18.5 and 25, especially at the lower end of the range, is more often associated with underlying disease, frailty, and a high risk for death.

A BMI in the underweight range (<18.5) is associated with an increased risk for death due to underlying diseases, frailty, and a lack of energy reserves.

A BMI in the obese range (>35) is also connected to a higher risk of death. The reason is less related to the BMI, but more so to the chronic diseases that develop in this high BMI range. In fact, 90% of seniors with a BMI over 35 are metabolically unhealthy and also tend to be frail.

The remaining BMI range, up to class 1 obesity, is not automatically connected to a higher risk for mortality. Around 30% of seniors in this BMI category are metabolically healthy.

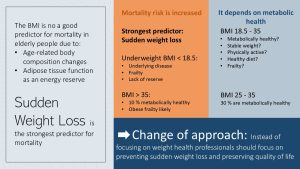

Should we completely ignore the BMI for seniors? The BMI should still be monitored. A sudden drop will require intervention. The focus should not solely be on the BMI. In addition, lifestyle and symptoms of chronic diseases should be monitored as well. This approach will enable early intervention.

Energy Reserves Are Important in Old Age

From the previous chapter, you know that muscle and organ function declines with age, especially in high age. In addition, the risk for both chronic and infectious diseases increases.

A normal part of aging is that it becomes progressively harder to bounce back from diseases, stress, or even exercise. Now, imagine seniors that are very thin before they contract the flu or need surgery. In both cases, the seniors will lose lean mass rapidly because of a reduction of physical activity. Recovery is always slower in older individuals. If said seniors do not have any energy reserves, recovery becomes harder.

This seems to be the reason why a BMI in the upper overweight range is indicative of good nutrition, as the senior has more nutrients and energy reserves to recover.

Sudden Weight Loss Is the Strongest Predictor For Mortality

Sudden weight loss has been identified as one of the key predictors of mortality in older populations. Sudden weight loss is defined as losing 4-5 % of original body weight within a year, or losing 10 % or more of normal body weight in 5-10 years. Keep in mind that we are talking about sudden weight loss at any weight.

Often this body weight loss includes lean body mass. A decline in lean body mass increases the risk of becoming frail. Developing frailty at any BMI range can send seniors into a downward spiral of aging-associated decline.

For this reason it is important to monitor the BMI or weight so health interventions can start early if sudden weight loss is detected. The aim of those interventions should be to maintain or improve quality of life.

The Development of Frailty Reduces Quality of Life And Longevity

What are you picturing when I talk about a frail person? Most likely, you think of a very thin and delicate person. This is not necessarily the case.

Frailty can come with thinness or obesity. The main descriptor is having little strength and a decreased ability to cope with everyday stressors. Frail people are vulnerable for disability, diseases, physical and cognitive impairments and geriatric diseases such as falls, delirium and urinary incontinence. In fact, today we see an early onset of frailty—particularly in obese people living a sedentary lifestyle—especially if people have developed chronic diseases over the years.

The driving force behind frailty is sarcopenia independent of weight.

What Is Sarcopenia and How Is Sarcopenia Diagnosed?

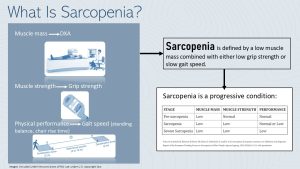

For the longest time, sarcopenia was defined as the loss of muscle mass due to inactivity or old age. However, recent studies did not find a direct connection between low muscle mass, disability, and mortality. Instead, those newer studies found a connection to disability, morbidity, cognitive decline, and lower survival times when both physical performance and muscle strength were impaired.

This led to a new definition of sarcopenia as low muscle mass combined with either low muscle strength and/or low physical performance.

It is important to know the signs of and/or get tested for sarcopenia development. The European Working Group on Sarcopenia for Older People (EWGSOP) has developed standards for diagnostic testing, which is recommended for individuals aged 65 and older:

- Physical performance: This is usually the first test conducted and is done so by observing patient gait speed (walking speed). The standard for a normal gait speed is anything greater than 0.8 meters per second. The gait speed can be measured in a hallway and requires only a measuring tape and some masking tape to mark start and end points. The patient has 2 meters to accelerate, then walks between 4 and 10 meters at top speed. This stretch is timed and the gait speed calculated.

- Muscle Strength: This is tested by determining the hand grip strength using a device called a Dynamometer. Squeezing the grip will display the amount of strength in kilograms with the normal being about 28.0-44.0 kg and 15.0-27.0 kg for males and females respectively.

- Muscle Mass: This is usually the last test conducted (expensive), and is most commonly done using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA). DXA testing is the most accurate at estimating the proportion of lean mass, fat, and bone density.

The final diagnosis of sarcopenia is done through a combination of these tests. In pre-sarcopenia only the muscle mass is low. Sarcopenia is diagnosed when muscle mass is low and either physical performance or muscle strength are lower than normal. In severe sarcopenia all three diagnostic criteria are too low.

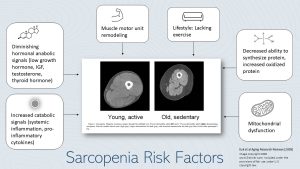

Who Is At Risk For Sarcopenia

People can develop frailty at any point during their life. In younger people this is usually due to disease.

Several risk factors that come with aging accelerate the risk for frailty.

A sedentary lifestyle leads to loss of muscle mass leading to a progressive loss of strength over time. This is aggravated by age-associated anatomical changes leading to a remodeling of the muscle motor unit. The anatomical changes limit communication between neuron and muscle fiber reducing the functionality of the muscle.

In high age metabolic changes make it harder to gain and maintain muscle. Protein synthesis becomes more inefficient (for example ER stress increases misfolding of proteins, chapter 30). Anabolic signals after physical activity promoting muscle growth such as growth hormone, IGF, testosterone and thyroid hormones decline in old age.

Elderly people do not just lose muscle mass, they also see an increase in ectopic fat. Ectopic fat infiltrates muscles fiber and reduces muscle functionality and strength.

Increased inflammation changes muscle cell function and mitochondrial dysfunction (chapter 30) reduces available ATP in the muscle cell. The elderly person has less energy to be active, tires faster and becomes more sedentary.

These aging-associated processes increase the vulnerability for sarcopenia by themselves. In addition, obesity and chronic diseases accelerate those processes and people can develop sarcopenia earlier in life.

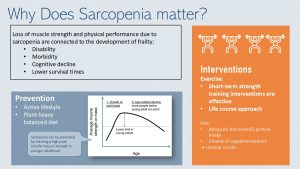

Prevention and Treatment of Sarcopenia

It is important to have an eye on the development of sarcopenia as a health care provider. Loss of muscle strength and physical performance is connected to physical disability and cognitive decline. Ultimately getting into a spiral of physical and cognitive decline increases the risk for morbidity and premature death.

The best way to prevent sarcopenia is having a healthy lifestyle in young and middle adulthood. Exercise and physical activity combined with an eating pattern based on whole grains, legumes, vegetables, fruits, nuts and seeds supplemented with meats, poultry, dairy and/or fish allows us to reach a high lean mass peak in our 30s. When you think about it, sarcopenia prevention is similar to osteoporosis prevention. Developing optimal bone density will give you a reserve when bone loss naturally occurs during aging. Developing a healthy level of lean body mass and muscular strength will give you a reserve during age-related lean body mass decline.

Does that mean that nothing can be done if sarcopenia develops with age? Here the research is promising. Short-term exercise interventions, including resistance training (about 5 months), have been effective in increasing quality of life and independence. Dietary interventions such as protein and vitamin D supplementation are researched as well, but with unclear results.

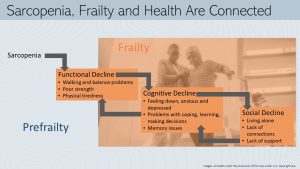

Sarcopenia Is the Driving Factor For Frailty

Failure to diagnose and effectively treat sarcopenia will inevitably lead to a state of frailty. When thinking of frailty, the word fragile comes to mind. If not handled with care, fragile objects can break/fall apart. Someone experiencing frailty must be handled and treated with the utmost care and receive plenty of support. Otherwise a cascading decline across multiple dimensions of health will begin.

Sarcopenia leads first to a functional decline. Once people cross a certain sarcopenia threshold, poor strength and physical tiredness lead to walking and balancing problems. After developing these problems, people with sarcopenia go out less often and spend more time at home, eventually limiting physical activity entirely. Frailty starts setting in.

A life once full of activity and social interaction completely changes. As frail people begin spending more time alone, they tend to feel down, anxious, and depressed. Mitochondrial dysfunction does not only reduce energy availability in muscles, but also affects the function of neuron in the brain. This leads to problems with coping, learning, and making decisions. This is called cognitive decline.

Social isolation due to the inability to move and the avoidance of challenging situations will lead to social decline. A frail person is less able to cope with unfamiliar situations such as meeting and interacting new people during an social event.

The three areas of frailty—functional, cognitive and social decline—are not isolated from each other. A healthy brain needs to be stimulated. Social isolation leads to less stimulation which hastens the cognitive decline. Feeling bored and alone increase depression symptoms. Depression and social isolation lead to less movement because there is no reason to challenge oneself.

You can clearly see how sarcopenia, once it results in frailty, can start a vicious downward spiral. Here are some seniors talking about frailty:

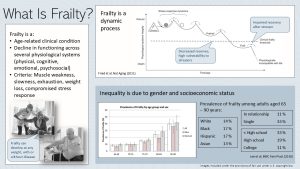

The Development and Progression of Frailty Is a Dynamic Process

Frailty is an age-related clinical condition connected to a decline in functioning across several physiological systems, as well as an increased vulnerability to stressors. Most aging people do just fine if they don’t experience any stressors (disease, psychological and environmental stress, injury). Experiencing a stressor reduces the efficiency of physiological systems. Once the person recovers from the stressor systems should go back to normal. In frailty the recovery is impaired and physiological functioning of multiple systems declines. with every new stressor functioning declines a little bit more.

Frailty is not a straight line to death though, rather the condition oscillates up and down until frailty spirals out of control and hastens death.

“The interconnected nature of frailty can lead to substantial declines across multiple forms of well-being. When I worked in a retirement home, multiple forms of frailty could be seen in the residents. From a displeased scowl directed at the nights dinner to a resident socially isolating themselves in the corner of the dining room, it was easy to see these forms of frailty unfold.

However, there were times when the socially isolated resident would meander over to a small table of three and engaged in small talk. I even walked into the four of them blissfully devouring dairy queen together, a interaction so humbling that branding the resident as isolated would have never have come to mind.

This example actually represents the dynamic nature of frailty. It’s not a simple linear decline towards dysfunctionality, but rather a wellbeing water slide with twists and turns that make some days great and others not so much.

What separates the bad from the good days is usually the amount of stressors someone with frailty faces. Being in the declined state that they are, even the smallest forms of stress can have a huge impact. Waking up to find that the cereal, a routine order for one of my residents, was accidentally misplaced with a fruit bowl was too much for this resident to handle and it sent them into spiraling rage for the next few days.

This dynamic, if not handled with care, will eventually lead to a dangerous state of frailty that contributes to health risks. Those most immediate risks include falls, delirium, and fluctuating disability. This inevitably leads to increases healthcare costs and can force some families to make the decision to admit an elderly relative to long-term care facilities or hospitals.” ~ Eric

Frailty is not equally distributed in our society. Women are more affected than men. The more financial resources a person has, the less the aging process is connected with frailty. People with a low income cannot afford to live in an environment with ample social stimulation, a variety of exercise, or eating a healthy diet. Low income and poverty will create constant, daily stressors.

Once frail seniors need to give up their home environment and live in a care facility, money determines their ability to live in an environment that offers cognitive and social stimulation, as well as exercise classes.

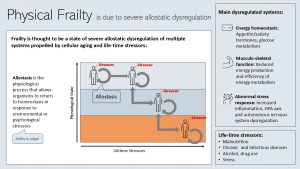

Understanding Frailty Better: Allostatic Dysregulation

Scientists wondered why frail individuals are so vulnerable to stressors. First things first: What are life-time stressors? Over the course of our life we will experience many stressors, some people more, some people less. Those stressors can be lifestyle related such as malnutrition, over-or undernutrition, developing chronic and infectious diseases, excessive alcohol and drug use or excessively hard physical work. Other stressors are environmental (weather, toxins) and psychological stress (work, social, discrimination).

Our body is working hard to maintain homeostasis within physiological systems and between systems. Stressors tend to throw the equilibrium off balance. Allostasis is the physiological process that allows organisms such as the human body to return to homeostasis in response to environmental or psychological stressors.

As lifetime stressors accumulate our physiological systems are less and less able to return to homeostasis. Allostatic dysregulation develops and our physiological state declines. Allostatic dysfunction is propelled by cellular aging and the accumulation of lifetime stressors. A person experiencing many stressors throughout life is more likely to decline faster.

Physical frailty is a state of allostatic dysregulation of multiple systems. The main dysregulated systems are:

- Energy homeostasis: In frailty energy intake is affected by dysregulated hunger and satiety hormone (more in chapter 33). The glucose metabolism is also dysregulated (insulin resistance, impaired glucose tolerance) and energy supply to cells is inadequate.

- Musculo-skeletal function: Energy production is impaired (mitochondrial dysfunction) and the energy metabolism is in general inefficient.

- Abnormal stress response: Frailty is connected with high concentrations of circulating inflammatory cytokines leading to systemic inflammation. The autonomous nervous system and the HPA axis are dysregulated leading to a exacerbated stress response.

Impaired energy homeostasis and musculo-skeletal function increase fatigue and exhaustion. The abnormal stress response to increased risk for diseases and an inability to cope with stress.

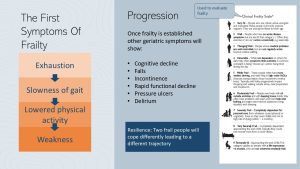

Progressing Frailty Is Connected to an Array of Geriatric Symptoms

The first symptom of frailty is usually excessive fatigue in response to normal daily activity. Consequently, the person slows down and eventually lowers physical activity entirely. The reduced physical activity leads to more muscle loss, and general weakness sets in.

Once frailty takes hold and continues to progress, other feared geriatric symptoms develop, including cognitive decline, decreased strength, and balance problems. These symptoms often lead to increased instances of falls—resulting in broken bones and injuries—which further reduces physical activity and leads to an accelerated cognitive decline. Once the frail person spends most of the day in bed, pressure ulcers and delirium are feared.

In clinical settings the clinical frailty scale (to the right in above graphic) is used to identify the degree of frailty and start appropriate interventions.

Keep in mind that people can cope very differently, and therefore the trajectory of frailty is very individual. A person that is still socially connected with plenty of family and friends will cope with a setback (for example from a fall) easier and recuperate. Or not, if the frail person is more depressed or anxious by nature and lacks support.

The living environment plays a huge role here; meaningful social connections, cognitive simulation, and continued exercising will keep the person on a much slower trajectory.

Frailty Prevention and Intervention Strategies Include Diet and Exercise

Because frailty can be present in normal weight, overweight, or obese individuals, sudden weight loss is the best predictor for sarcopenia, frailty, and ultimately premature mortality. Spotting the sudden weight loss and starting lifestyle interventions can prolong life and increase quality of life.

The scientific understanding of the effectiveness of nutrition intervention is limited. No “perfect blueprint” has been found. Despite this, suggested dietary interventions generally prioritize reducing severe obesity for both easier physical activity and reduced inflammation. Weight loss should be slow to avoid too much loss of muscle mass. Generally, these goals are supported by eating a plant-heavy diet rich in antioxidants and flavonoids.

At the moment, the recommended diet is a Mediterranean-style diet because studies have demonstrated a positive impact on inflammation, chronic diseases, and cognition. Because not all elderly people will accept a Mediterranean diet, similar culturally-appropriate diets such as the DASH diet are good choices as well.

Once frailty has developed, the main goal of the dietary intervention is to prevent sudden weight loss, especially from muscle mass. Research has focused heavily on increased protein intake and vitamin D supplementation to improve muscle mass. Other intervention studies center around omega-3 fatty acids, and antioxidant supplementation reduce inflammation and improve cognition. Although clinical supplementation trials have shown mixed results, the intake for these nutrients should be adequate to support maintenance of muscle mass and build reserves.

As always, prevention is better than intervention. A healthy, plant-heavy mixed diet will be the first important preventative step to avoid sarcopenia and frailty. A focus on protein intake is more important As people reach old age a focus on adequate protein intake will become increasingly important.

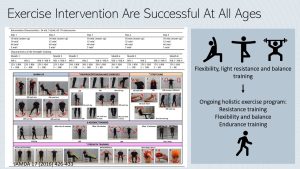

Starting an Exercise Regime Improves Quality of Life Tremendously At all Ages

Starting an appropriate exercise program is essential for increasing strength and reversing frailty. Studies evaluating exercise programs for frail people have shown to be very successful in reversing frailty and increasing independence.

The program should start out with light resistance, balance, and flexibility training. The aim is to improve muscle mass, independence, and balance. This will increase the ability to complete daily chores, such as dressing and moving around, and reduce the risk of falls.

Once initial improvement is reached, the exercise program should continue and address the three key areas of exercise programming:

- Resistance: Resistance training should be light and progressive, target all major muscle groups, and be done 2-3 times per week. Increased muscle strength will help with everyday mobility and improve balance.

- Flexibility & Balance: Flexibility training should be reinforced everyday through passive stretching, while balance training should be done 2-3 times per week.

- Cardiorespiratory: Once strength has returned, moderate aerobic activities such as aerobic exercise classes, walking, dancing should start. Intensity should be enough to elevate the heart rate but not lead to total exhaustion. Doing so for 20-30 minutes, 3 times per week is recommended.

Unlike diet interventions, exercise intervention programs have shown impressive results in treating sarcopenia, and ultimately frailty. Resistance training in particular has been clearly associated with improved gait speed and increased lean muscle mass.

Interested? Want to Know More?

Frailty is the result of a combination of life-time stressors—hard physical work, obesity, disease, mental health, life events—and age-related dysregulation of multiple systems. Here is an article summarizing how driving factors impact systems resulting in frailty.

Fried LP, Cohen AA, Xue QL, Walston J, Bandeen-Roche K, Varadhan R. The physical frailty syndrome as a transition from homeostatic symphony to cacophony. Nat Aging. 2021;1(1):36-46. doi:10.1038/s43587-020-00017-z

Editor: Eric Hanzel, Meryn Potts, Sydney Christensen

NUTR251 Contributors:

- Spring 2020: Audrey Freyhof, Tina Dinh, Jacob Sautter, Caleb Licking, Julia Curtis, Shane Rapp, Krissy Krager, Dylan Fruhling, Tina Dinh, Kendyl Heuertz, Madison Yourstone, Hailie Slepicka, Brittany Southall, Patrick Fisher

- Fall 2020: Peyton Hainline, Miles Judson, Megan Appelt, Pierce Krouse

Basic functional unit of the skeletal muscle comprised of the motoneuron and the muscle fiber innervated

the tendency to maintain stable balance between interdependent elements of a system

Feedback/Errata