26 Puberty, Body Image, And Eating Disorders

Sabine Zempleni and Sydney Christensen

Embedded from Getty Images

As teenagers make their way through adolescence, their body changes drastically. Sometimes it seems changes happen overnight. Hormonal changes change how the brain is functioning causing the teenager to become hyperaware of themselves and their environment.

The combination of hyperawareness and drastic physical change along with the necessity to develop a new body image make adolescents especially vulnerable for eating disorders. This process is aggrevated by external factors such as family, peers, culture and social media.

You Will Learn:

- Hormone surges during puberty affect brain development and various behaviors in teens

- Teens may experience body image issues as their bodies go through body composition changes and emotional development

- Because of all of the physical and emotional changes, teens are especially vulnerable to eating disorders

- Body dissatisfaction is a predictor for the development of eating disorders and related body image distortions

- We see various eating disorders in teens including anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder as well as other disordered patterns such as orthorexia, body dysmorphic disorder, and muscle dysmorphia

- Today we primarily focus on eating disorder prevention

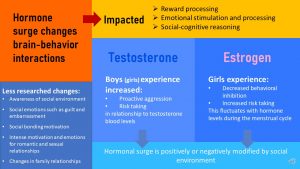

Hormones Surge During Puberty and Change Brain-Behavior Interactions

When we think of puberty we tend to think mostly about physical changes such as secondary sex characteristics and becoming sexually mature. What we often forget is that these these hormonal surges cause a range of new emotions and behaviors.

Sex steroid hormones are surging during adolescence and the effects of these hormones transition the child into adulthood. One major target of sex hormones is the brain causing remodeling and new neuronal growth. The areas of brain most affected are those that regulate reward processing, emotional stimulation and processing, and social-cognitive reasoning. Interestingly, the development of the child’s brain into an adult brain is not completed until the early 20s and takes longer in males than females.

One of the players is testosterone. Testosterone is the main sex hormone in males, but females experience a subtle increase as well during puberty. Increasing testosterone levels are connected to heightened proactive aggression and more risk taking. The testosterone increase varies from boy to boy and ultimately men will end up with a range of testosterone blood levels. This is determined by genetics, but as we have seen in the puberty chapter also by weight. The likelihood of proactive aggressive behaviors and risk taking increase as the amount of testosterone blood levels increase.

In addition, increased testosterone stimulates the reward system in the brain and drives teens—boys and girls—to seek out rewards especially social rewards.

Increasing estrogen blood levels in girls decreases behavioral inhibition and also increases risk taking. Interestingly these behavior changes fluctuate with the menstrual cycle as estrogen blood levels first increase reaching a maximum at ovulation and then decrease. Males also experience a subtle increase of estrogen during adolescence and the blood levels are partially weight dependent.

Does this mean that adolescents are now completely determined by their hormones? Are boys who have high testosterone blood levels doomed to be aggressive? Are all girls taking risks in the middle of the menstrual cycle?

Of course not. Studies also show that those behavioral changes can be negatively or positively modified by the social environment the teen lives in. Small behavior changes due to testosterone surge can be amplified by an environment that promotes aggression. On the flipside living in a social environment that helps teens manage those impulses will result in less aggression or risk taking.

On a side note, here is another interesting effect of hormonal surges during puberty. Exposed to the surging sex hormones the brain becomes slightly more light sensitive during puberty. This did not have a huge impact 200 years ago. Lacking electricity, people stayed up a short time at dim candle light but usually went to bed after dark. In todays environment, bright, electric light and lately the exposure to ample amounts of blue light devices expose the brain to much more light in the evening. The impact of the artificial light on the brain is amplified by puberty and the circadian rhythm shifts to a later time in the day.

Other important, but less researched, behavioral changes due to hormonal alterations of brain regions involve an increased awareness of the social environment, feeling guilt and embarrassment intensely, changes in family relationship, a motivation to bond socially, and of course an intense motivation connected with sometimes overwhelming emotions to seek out romantic and sexual relationships.

While the teen matures physically and sexually and starts to have adult drives and emotions, brain development lags behind those developments in some brain regions. The ability for social-cognitive reasoning is not fully developed until the early 20s.

All of these changes enable the teenager to make great developmental strides, but during this development major changes in self-perception, feelings, and behaviors can trigger anxiety. The remaining chapter we will focus on how these major changes, physically and mentally, impact the development of a new body image. You will also learn that if this process of developing a new body image goes wrong leading to body dissatisfaction the risk for developing an eating disorder will be high during adolescence.

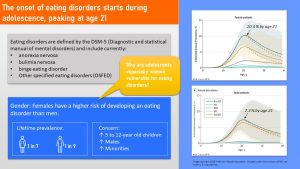

Adolescents are Vulnerable to Eating Disorders

Eating disorders are diagnosed using the DSM-5, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, published by the American Psychiatric Organization. The DSM-5 includes diagnostic criteria for anorexia nervosa, binge eating disorder, bulimia nervosa, OSFED (Other Specified Feeding or Eating Disorder), and a few more that are not directly relevant to adolescents.

Eating disorders have a genetic component. For example, female relatives of anorexia nervosa patients have a 11 times higher risk to develop anorexia as well. This relationship is less studied for other eating disorders, but evidence so far points to a genetic component as well.

In addition to the models how eating disorders start, ample research is available that shows that adolescents are especially vulnerable to eating disorders.

As the study above shows, the onset of eating disorders tends to take place during adolescence with the prevalence reaching a peak around age 21.

The number of young adults who are diagnosed with any eating disorder by age 21 is 10.4 % for women and 7.3 % for men.

Men are less likely to develop an eating disorder during their lifetime than women, 1 in 7 women versus 1 in 9 men. During adolescence, the gender difference is much larger with a female to male ratio of 9:1.

Interesting is also that eating disorders generally seem to be less prevalent in minority groups. Initially it was thought that the lower prevalence in Black youth was due to a culture of better body acceptance. However, more recent studies show that individuals from minority groups in the US are less likely to seek help for eating disorders. This could mean that the prevalence is instead under-reported and thus underestimated.

The good news is that during the last years the prevalence of EDs (eating disorders) did not increase too much, but there are a few concerning trends:

- EDs are increasingly identified in children as young as 5 to 12 years.

- Increasing prevalence rates are seen in males.

- Increasing prevalence rates are seen in minority youths.

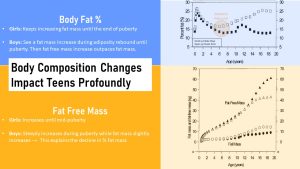

Profound Body Composition Changes Combined With the Emotional Development Increase the Vulnerability For Body Image Issues

When we educate about puberty the focus tends to be entirely on the secondary sex characteristics described by the Tanner stages: Breast development, female and male genital development, and hair growth.

We tend to forget though that the body of an adolescent transforms in its entirety. Young men and women not only grow taller but their skeleton, muscles, and body fat change profoundly into an adult body determined by the blueprint of the DNA. The skeleton changes from an androgyn child shape into a bone structure that emphasizes specific body parts. Wider hips in most girls and broader shoulder in most men. In girls adipose tissue appears around the hips and thighs, and boys begin to build muscle to various degrees.

Those changes in body composition can start at a very early age, giving some teens an adult-like look at the beginning of middle school while others may look childlike until the end of middle school and sometimes into high school. Keep this in mind when looking at the description of the average body composition changes in the infographic above.

Look at the upper right quadrant of the graphic. It depicts the percent body fat changes throughout childhood and adolescence. The adiposity rebound preparing for puberty is distinctly visible for body fat percent as well. Girls continue gaining body fat until the end of puberty.

On the other hand boys keep gaining body fat after the adiposity rebound until the beginning of puberty. Then boys seem to lose body fat percentage. During puberty, the increasing testosterone secretion in boys triggers the gain of fat-free mass, more specifically muscle. The rapid FFM gains outpace fat mass gains.

The scale of the second graph on the bottom right corner lets the adiposity rebound bump vanish. Boys keep gaining small amounts of fat mass but much less than girls.

Since boys have higher testosterone levels, the fat free mass gain is much more visible in boys. Girls only see a modest increase in muscle mass due to their lower testosterone levels.

Keep in mind that we look at those changes from a scientific position and focus on averages. The physical develop can vary widely from child to child. The onset of puberty varies widely. The genetic blue-print determining hormone production and overall body shape varies widely. Lastly, eating habits and physical activity can modify the physical development of the body as well determining fat mass, lean mass and sex hormone production.

Adolescent or pre-adolescent becomes acutely self-aware and needs to get used to and accept the new body. This can be a stressful and confusing time. Adolescents that are well supported by family and friends generally make the shift growing into a healthy adult without problems. For other teens, this time period can be especially difficult.

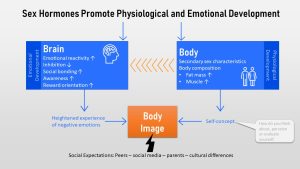

Physiological and Emotional Development During Puberty Will Require the Teen to Develop a New Body Image

As we previously discussed, sex hormones don’t just change the secondary sex characteristics and body composition, but they also impact brain development.

This includes a heightened emotional reactivity combined with reduced inhibition—parents are all too familiar with the sudden emotional outbursts —and a need for social bonding and acceptance. Combined with an increased body and social awareness, and a general reward orientation the teen experiences negative emotions easier and more intensely.

Physical changes can solicit those intense negative emotions too, resulting in a reduced self-acceptance. Think about girls that go through puberty early while their friends are still looking like children. Think about the boy going very late through puberty while his friends are already dating. Think about teens who end up with a body they are not happy with due to the inherited DNA blueprint .

We need to keep in mind that those emotions and difficulties in accepting and loving this new body are normal.

Over time brain and body development—the emotions the teen is feeling, what the teen sees in the mirror or Instagram pictures, what the teen hears from family and peers—will inform the picture of the body that is forming in the teen’s mind. This mind picture and how the teen approaches it is called the body image. The body image is a multidimensional construct involving:

- Body-related behaviors (e.g. checking behaviors)

- Perception of body characteristics (e.g. estimation of one’s body size, weight or shape)

- Cognitions, attitudes, and feelings toward one’s body

Body Dissatisfaction Is a Predictor for the Development of Eating Disorders and Other Related Body Image Distortions

Since teens do not live in a happy bubble, there are many external factors that can profoundly impact the development of the body image. Parents and extended family sometimes subconsciously set standards that the teen is compared to. This can range from a cultural ideal—for example some cultures prefer very thin, slight girls while other cultures prefer more womanly, curvy girls—to an older sister, brother, or cousin as an ideal. Some families are accepting while others pressure the child from an early age to meet the ideal.

Even before social media existed, peers set the ideal. The need to fit in with a social group kept the pressure on. Today, external pressures by family and peers are amplified by social media. Coming from a time when teens were photographed by parents and peers—rarely and on film—I had a completely different experience during puberty. The pictures were taken one time as developing film was expensive, and the pictures were sometimes flattering, but more often not.

There is increased pressure to take the perfect picture for social media, pose to look thin, and edit before posting. This is followed by constant judging by the teen, peers, and family. While watching my daughters grow up, I found this situation incredibly hard and struggled as a parent to help them develop body acceptance.

When left alone, most young children are unaware about their body size and shape. The devopment of a body image starts developing during elementary school and puberty, the hormonal shift increases the awareness. Over time teens forms an mental image of their body. This can be initially very skewed with a heavy focus on body parts the teen does not like. This is normal.

Some teens overcome those dislikes and learn to accept, like, even love their genetically given body. Others develop an intense body dissatisfaction. Body dissatisfaction is defined as the negative, subjective evaluation of one’s body and can impact mental and physical health profoundly.

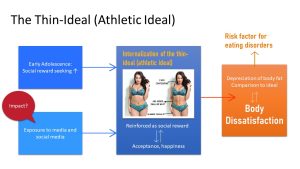

One key factor in body dissatisfaction is the idealization of a specific body type.

During the last decades this ideal body type was for women the ‘thin ideal’, a very slight body with little fat and muscles, and most research about body dissatisfaction is based on this ideal. Lately though, the ideal in the US shifted toward a body that has still little fat but has muscles in the right places. This ideal is called ‘fit-ideal’, ‘toned-ideal’, ‘athletic-ideal’ or ‘thin-muscularity ideal’ (you see the science is still in the process of catching up).

It is thought that the combination of social reward-seeking triggered by the sex hormone surge in combination with ample amounts of social media exposure might lead to an internalization of the societal body ideal. Feeling acceptance is a major social reward during puberty which can reinforce and internalize the ideal. If the ideal is not met it can lead to body dissatisfaction. Body dissatisfaction is defined as the negative thoughts and feelings about one’s body and one of the risk factors for eating disorders.

In addition, body dissatisfaction is also connected to mental health problems and negative health behaviors

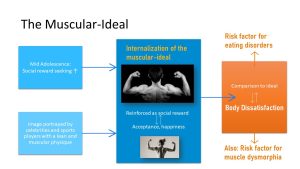

While less researched, body dissatisfaction in men can develop in a similar way. For men the ideal is the muscular-ideal. While this ideal so far was applied mostly to men, increasingly women are held up to the muscular-ideal as well. Research shows that the muscular ideal can contribute to body dissatisfaction. Body dissatisfaction fueld by the muscular ideal is not only a risk factor for eating disorders but also for muscle dysmorphia.

Both, the female thin-muscular ideal and the male muscular-ideal might also be connected to over-exercising.

Not All Teens Going Through Body Dissatisfaction Will Develop an Eating Disorder

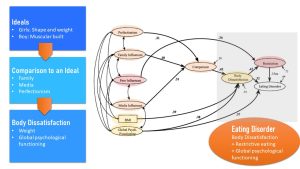

Not every teen who hates their body or experiences body dissatisfaction will necessarily develop an eating disorder. The road from body dissatisfaction to eating disorder is multifactorial.

Here is one of the scientific models that tries to explain what we know about the connection of external influences, body dissatisfaction, and eating disorders. In a nutshell: It is complicated with many moving factors.

Tripartite Influence Model; Van den Berg et al. (2002)

- The teen is vulnerable due to hormonal shifts triggering brain development that lead to an emotional stable adult over time. During this time the teen experiences emotions more intensely. Rapid physical changes and the timing of these changes leave many teens unsettled.

- External influences determine the ideal the teen compares against. The first external influence in the life of a child are parents and family. For example, parents comparing their children to a thin-ideal and then pushing their daughters to diet or restrict food at an early age can have major impact on how girls feel about their body before puberty even starts. This makes it important for parents to understand that children need to eat healthily and be physically active, but need to go through the adiposity rebound to enter puberty.

- A perfectionistic personality is a risk factor in itself, but the family can attenuate or aggravate this character trait.

- During the last decades, the media and social media have heavily informed the ideal that children, teens, and adults are compared to. This, in turn, informs how peers and family set an ideal teens compare themselves to.

- Studies also show that teens with an increased BMI tend to have more body dissatisfaction.

Based on those influences a social environment evolves that either pushes the comparison to the socially sanctioned ideal or supports the child in developing body acceptance. If the socially or culturally sanctioned ideal is not reached, the teen, experiencing negative emotions more intensely, feels body dissatisfaction. If the ideal is reached the teen feels rewarded.

The degree of comparing promotes body dissatisfaction. This alone will not necessarily lead to eating disorders though.

Body dissatisfaction together with existing restricted eating behavior is setting the ground for an eating disorder. Restrictive diets ranging from omitting all carbohydrates to all animal products, creating lists of bad and good foods are widely promoted in the media. Peer influences seem to have a large influence on restricting the type or amounts of foods that are eaten.

Eating disorders can easier develop when the teen lacks global psychological functioning. Global psychological functioning will determine if the teen copes with the body dissatisfaction or internalizes it. Global psychological functioning includes positive energy, a positive outlook in life, and emotional regulation. This tends to be in an uproar during teen years. Psychological functioning also includes having a purpose in life and being optimistic.

The combination of these three factors—body dissatisfaction, restricted eating behavior and global psychological functioning—seem to be able to explain the development of eating disorders and allow for targeted prevention or treatment strategies.

In conclusion, developing an eating disorder is a complicated process and research is still ongoing what factors exactly contribute. Here are the facts we know so far:

- The hormonal surge during puberty increase the vulnerability for eating disorders. This includes emotional development and a rapidly changing body.

- A crucial factor is the development of the body image.

- The teen’s environment determines the ideal most teens compare themselves against. This can lead to body dissatisfaction.

- It is thought that eating disorders develop at the intersection of body dissatisfaction and already existing restrictive eating behavior. This is modulated by the teen’s global psychological functioning.

What Are The Eating Disorders We See In Teens?

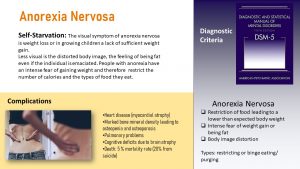

Anorexia Nervosa

Anorexia Nervosa has the highest mortality rate of all psychiatric illnesses. The term means neurotic loss of appetite and was first reported in the scientific journal Lancet in 1888. Anorexia is much more than than just not eating. Here are some quotes from women suffering from anorexia nervosa:

“To someone who has never suffered from or studied the disorder, it can be difficult to understand what about this disorder could drive a person to suicide… anorexia leads to tremendous physical, mental, and emotional pain.”

“The anorectic operates under the astounding illusion that she can escape the flesh, and, by association, the realm of emotions.” – Marya Hornbacher

“I’ve gone through stages where I hate my body so much that I won’t even wear shorts and a bra in my house because if I pass a mirror, that’s the end of my day.” – Fiona Apple

These quotes do not just demonstrate the thought-process when a person suffers from anorexia nervosa but also explains another important fact. People suffering from anorexia have a profound ambivalence about recovery.

An anorectic might not be willing to recover. Three in four patients with anorexia nervosa make a partial recovery. But only 21% make a full recovery, which is likely to last long-term. These findings are reported by 387 patients in a study led by UC San Francisco and published in the International Journal of Eating Disorders in 2019.

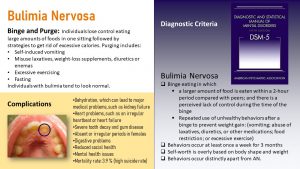

Bulimia Nervosa

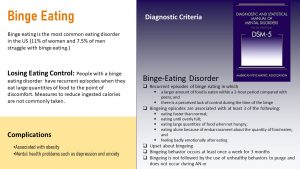

Binge-Eating Disorder

“In the end it was impossible to exercise more or eat less. It was impossible to vomit more or feel worse. Everything was anxiety. I was unable to exercise to remove the anxiety. I had terrible pain and felt like shit. At the same time, I felt that if I was not exercising, I would die. Then I would have to kill myself.” (von Wachenfeldt, 2010)

Other Related Disordered Eating and Body Image Patterns

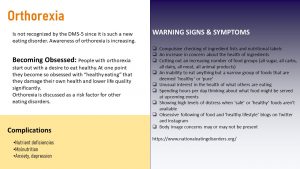

Orthorexia nervosa starts innocently with the desire to eat better and improve health but morphs into an eating obsession. The term orthorexia, meaning correct appetite, was proposed in 1998 but is not acknowledged by the DSM-5 as an eating disorder at this point. One reason for this is that the scientific community is still discussing what it is. Is it a disorder, a behavioral addiction, or an extreme eating behavior?

Orthorexia is just emerging as an important research topic . It is thought that orthorexia has its root in healthism. Emerging in the 1970s and gaining speed during the last two decades, this view of health is the dominant ideology in developed Western societies. Healthism starts with health promotion efforts and is contorted by popular media and advertising.

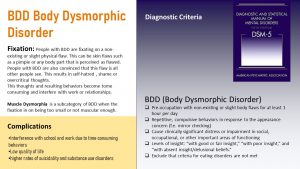

Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD) is not an eating disorder but is also common in adolescence. Many teens are not happy with their body and can have a distorted body image. Ask any teen what body part they like least, and they don’t have to think long. This is part of the normal process of growing into the adult body and forming a body image.

This process can go very wrong though. Teens with BDD are obsessed with certain body parts, particularly related to their face, head, weight, or body shape. They are overly preoccupied and spend hours thinking about it.

A specific form of BDD is muscle dysmorphia. Individuals with muscle dysmorphia are preoccupied with the perception that their body is insufficiently large and muscular. Their lives are consumed by activities aimed at increasing muscularity. They spend hours weightlifting and following extreme diets and tend to use body enhancing drugs.

In addition, these individuals experience severe distress about how their bodies are viewed by others.

Treatment and Prevention

- Belief in the cultural body ideal

- Pressure to be thin

- Body dissatisfaction

- Dieting and restrictive eating

- Depressive symptoms

Research that tests the effectiveness of specific intervention programs is still scarce.

Prevention strategies need to be interdisciplinary. Medical, nutritional, and mental health care professionals need to be aware of behaviors and physical signs that might indicate an eating disorder. Health care professionals need to develop skills that allow them to begin a conversation about the concerns they have.

Each one of us can also contribute by becoming aware how we talk about body weight, body shape, and eating. It is definitely not easy to balance between health education and promoting a positive body image independent of weight.

Interested? Want to Know More?

- https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/eating-disorders/what-are-eating-disorders

- https://www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/

- At UNL: If you suspect you or a friend has an eating disorder contact https://caps.unl.edu/.

- van den Berg P, Thompson JK, Obremski-Brandon K, Coovert M. The Tripartite Influence model of body image and eating disturbance: a covariance structure modeling investigation testing the mediational role of appearance comparison. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53(5):1007-1020. doi:10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00499-3

Social cognition refers to the processes that enable humans to interpret social information and behave appropriately in a social environment. As in other domains of cognition, social information processing relies initially on attending to and perceiving relevant cues. Those cues can stem for example from face and emotional recognition.

Fat free mass: Body Weight - Fat Mass

Keep in mind that FFM is not equal LBM (lean body mass)

Feedback/Errata