27 Teen Athletes: Eating to Fuel Before Thinking About Supplements

Nicole Legler and Sabine Zempleni

There Is Not One Teen Athlete

If you take 100 random adolescents ages 14-18 years old, you would likely see 100 adolescents that were different heights, shapes and sizes. Even if you would line up one hundred 14 year old male athletes you would see a wide range of boys. As you view these 100 different 14 year old athletes, some would look bigger and more muscularly built where as some, still at the beginning of puberty, would look small, child-like and drastically less muscular.

- Early adolescence (pre-teens): 10 – 13 years

- Middle adolescence: 14 – 17 years

- Late adolescence: 18 – 21 years

Common themes seen are How come this athlete in my same grade is so much bigger than me or How can I build muscle and get bigger as fast as possible or What diets or supplements are best to support my athletic goals? All of these questions cannot be answered with any simple piece of advice. As nutrition or sports professionals we must address the uniqueness of this population, and nutritional recommendations are then given after assessing a multitude of factors.

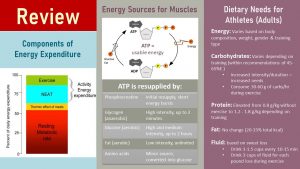

Before looking at the nutritional needs of teen athletes in more depth here is a quick review of energy expenditure, energy sources for the muscle, and dietary needs for the adult athlete:

You Will Learn:

- The teen athlete is uniquely different from adult athletes. This includes an ongoing increasing BMR and slightly increased insulin resistance.

- The slightly increased insulin resistance results in a somewhat decreased ability to store glycogen and increased fat utilization during exercise compared to adults.

- The research on how to fuel adolescent athletes is limited. Adult research results and recommendations tend to be extrapolated to teen athletes.

- The basis for fueling teen athletes (and adult athletes) are the Athlete Performance Plates.

- Trendy diets for exercise performance lack research supporting the claims made. Positive research results usually apply only to niche groups of high performance adult athletes.

- Performance enhancing supplements might effect adolescent athletes differently than adult athletes. Very little research is available.

The Difference Between Exerciser and Athlete

When reviewing nutritional recommendations for athletes, we must first understand how we define this population. Is every teen participating in high school sports automatically an athlete? How about participating in competitive club sports? Does everybody participating in sports need specific approaches to fuel their muscles?

The following criteria have been establish to describe athletes and most, if not all criteria should be met:

- Training aims to improve sports performance

- Actively participating in sport competitions

- Formally registered in a sport organization, team, or league that participates in competitions

- Sport training and competition is the majority of their activity or focus; devoting several hours most days for these activities

Teen Athletes Are Uniquely Different From Adult Athletes

The Teen Athlete Needs to Adapt Continuously to a Growing BMR

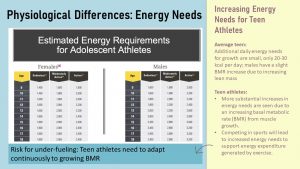

Total energy expenditure in adolescents includes BMR (basal metabolic rate), energy for daily physical activity, TEF (thermic effect of food), thermogenesis, and energy expenditure for growth. Compared to an adult two components of the energy expenditure are unique to the growing teen: Energy expenditure for growth and continuously increasing BMR due to increasing lean body mass.

What comes to mind first when we think about a growing teen is the energy cost of tissue deposition. Since the teen is growing so rapidly it must be large? Surprisingly this is not the case. Studies measuring the energy expenditure for growth estimated that the cost for growing new tissue is be approximately 20 kcal/d, increasing to 30 kcal/d at peak growth velocity. If you think in terms of food this is the equivalent of a apple quarter. A small amount amount. Clearly this does not explain the rapidly increasing energy expenditure during puberty you see in the table above especially for boys.

This energy expenditure increase is explained by the increasing BMR. When you think back to the changes in body composition teens shift body composition towards lean mass (even if girls also accrue additional fat mass). The increasing LBM will require increasing amounts of energy to maintain. This also explains that boys start to have higher energy needs than girls since they grow more lean mass.

During growth teens need to adapt their energy intake over time. For a teen athlete this will pose a more pronounced problem. A teen athlete training several hours per day will need to adapt to the normal increasing energy expenditure that comes from the increasing BMR, and a little for tissue deposition, but also to the energy expenditure stemming from training and competition. There are not many studies in the area, but a study conducted in Danish teen elite soccer players showed that those teens did not keep up with the increasing demand for energy. This is a problem because under-fueling along with under-hydration is limiting sports performance.

Physiological Insulin Resistance Changes Slightly How Energy-Yielding Nutrients Are Used

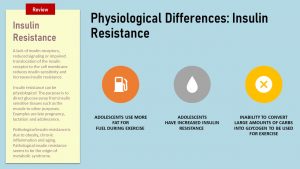

While there is limited research on adolescent athletes, the few existing studies indicate that adolescents have also physiological insulin resistance directing some glucose away from the muscle. This may impact sports nutrition recommendation. At this point, due to the limited research in adolescent athletes, adult sports nutrition recommendation are just extrapolated to adolescents. It is not clear at the moment if the physiological insulin resistance is pronounced enough to require separate recommendations for optimal performance, but it is definitively interesting to think the situation through.

We met physiological insulin resistance before. Pregnant women during the last trimester see decreasing insulin sensitivity and that directs glucose away from the muscle to the fetus. The same happens in breastfeeding women. Glucose is directed towards the breast for lactose production. In both situation the woman starts using more fat as an muscle energy source. The situation is similar in adolescents going through puberty. It is unclear though due to a lack of research where the glucose is directed, but lower insulin sensitivity during periods of puberty are not a concern.

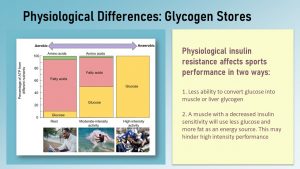

More fat for fuel: When it comes to fueling for optimal performance the lower insulin sensitivity should be addressed when recommending nutrition to fuel sporting events. Physiological insulin resistance is reflected in slightly higher blood glucose levels and less ability to convert glucose into muscle glycogen*. [1] elevated As a result, adolescents, unlike adults, tend to use less glucose and slightly more fat as fuel during exercise.

Lower Muscle Glycogen Stores: Insulin resistance also directs glucose away from glycogen production and therefore adolescents may not be able to convert large amounts of carbohydrates into muscle glycogen prior to exercise like adults can. High carbohydrate intake is recommended for adult athletes before and during exercise performance to maximize glycogen stores and support high-intensity exercise. For teen athletes carbohydrate recommendations will still likely be elevated to support physical activity, but may need to be lower than the adult recommendations if there are signs of insulin resistance or hyperglycemia during puberty.

In fact, research has shown that adolescents tend to have lower muscle glycogen stores when compared to adults. Due to a lower glycogen storage capacity, adolescents will likely experience accelerated rates of fatigue. These differences have been noticed through various studies and should be considered when working with adolescent athletes. Sports dietitians need to keep two factors in mind when devising a nutrition plan for the teen athlete. Is the teen going through puberty and does the sport depend on fast energy from muscle glycogen?

Looking at what sports is most affected by glycogen stores, you can see on this figure how different sports utilize energy-yielding nutrient. Glucose is the product of glycogen. So, sports that are moderate intensity to high intensity, or sports that are long in duration (>60 min) will utilize a substantial amount of glycogen stores. The higher the intensity or longer the sport, the more glycogen is needed to support the needs of this exercise. Since adolescents may have decreased glycogen stores, fueling with carbohydrates during these sports will be important to support energy needs. For example, a football player may benefit from sips of a sports drink between drives to provide some quick carbohydrates to fuel the anaerobic use of glucose for explosive sprints.

More Reason to Think Individual Athlete When Working on a Nutrition Plan For Teen Athletes: Gender Differences

In addition to general physiological differences—genetic, timing of puberty—there are also differences based on gender that begin to be noticeable during early and middle adolescence. Keep in mind that differences in body composition will affect each sport differently. Here are the key gender differences for adolescent athletes:

- Girls who have gone through puberty early or are deemed “mature for their age” are taller and heavier than their peers.

- Females begin to have significantly higher body fat percentages than males.

- Increased hormone levels such as estrogen for females and testosterone for males are seen. Males are able to build muscle at an increased rate compared to females.

- Not so much a physiological difference, but important: Female adolescent athletes show lower carbohydrate intakes compared to their male counterpart. This may cause earlier fatigue and limited ability to progress the same way as those who are sufficiently fueled.

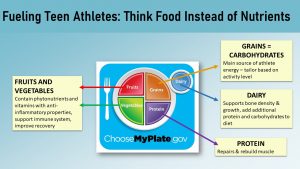

Before Even Thinking About Supplements: Teens Need to Fuel Properly Using the Athlete Performance Plates

Although we’ve established that adolescent athletes should be treated as a unique population separate from adult athletes, sports dietitians still use the general guidelines for adult athletes to make recommendations for adolescent athletes (not enough research to generate specific teen recommendations).

Each food groups contributes benefits when fueling an athlete. The grain group—note: half of the grain intake should be whole grains—will provide glucose, which is for medium and high intensity sports the most important fuel. Carbohydrate is tailored depending on the physical activity level using the performance plate. Protein, not necessary all from energy sources, supplies amino acids to grow lean mass as well as maintain and repair the existing lean mass after exercise. Dairy will also contribute protein and easy digestible carbohydrates, but also will be essential for optimal bone mineralization since dairy is the best source for calcium. Fortified milk also provides vitamin D to enable optimal calcium absorption.

Fruits and vegetables provide more glucose as an energy source, but their main purpose when it comes to exercise is to deliver phytonutrients and vitamins with anti-inflammatory properties. During exercise muscle fibers will micro-tear (the post-exercise soreness and DOMS) and any injury will illicit and inflammatory immune response starting the repair process. Anti-inflammatory nutrients keep this immune response in balance. For most athletes the hope is more effective training with reduced inflammation.

A Sports Dietitian Will Tailor MyPlate to the Demands of Training and Competition

Extensive research in adult athletes lead to the design of the Performance Plates sports dietitians are using to work out nutrition plans for athletes. The Performance Plates are a collaboration between the United States Olympic Committee Sport Dietitians and the University of Colorado (UCCS) Sport Nutrition Graduate Program and are widely used in the USA and worldwide.

Why Are Sports Dietitians Not Counting Macros and Micro-Nutrients?

The first thing you will notice looking at the performance plates is that the recommendations are given as foods within meals and not as you often see in the media as meeting recommendations for individual nutrients.

The idea that “macros” and “micros” can be tracked using an app suggests a precision that is not actually there. Since we do not know the exact nutrient need of a person, recommendations are designed to be high enough to meet nutrient needs of 98% of individuals. This means that 98% of the population would meet their for this nutrient with less and 2 % of the population would need more of the nutrient than the recommendation.

Using an app the average nutrient composition of foods is used. Depending, for example on the apple type or when the apple was harvested the actual nutrient composition can vary widely and be different from the average apple used to calculate the intake.

Therefore, nutrient recommendations are used to make sure that intake is sufficient if dietitians generate eating plans for specific diseases or a group of people for example in schools, hospitals, dining halls. The recommendations also are used for research purposes. For all other purposes food and meal-based recommendations are appropriate.

There are three different performance plates depending of the trainings intensity and competition. You’ll notice that each plate resembles a MyPlate, however different food groups will be recommended in different amounts based on training level. Looking at the three plates the main shift centers around the grain amount and type, as well as fruits. The protein and dairy group remain unchanged. Times when refined grains are recommended would be immediate prior or following exercise as this provides us with quick energy.

Athlete’s performance plates are chosen on a daily basis. Most days the plate for moderate training will be appropriate, but before a competition or increased training intensity the athlete should switch to the hard training/game day plate. During a rest day the easy training plate might be appropriate.

The Easy Training day reflects a typical day for an adolescent, an athlete who is taking a rest day, or an adolescent doing light activity. This plate matches the MyPlate eating pattern and promotes a balanced intake of each food group. Since the athlete is not expending any significant energy during a practice or competition, their energy needs specific to the food groups stays the same as typical recommendations for their age group.

Most teen athletes will be in the moderate training plate most of the time. Notice that there is additional fruits outside of the typical plate, showing that additional energy intake is recommended to support the additional energy expenditure due to training and competition. This additional energy need should be covered in form of nutrient-rich carbohydrates from fruits and grains.

The plate also shows an increased proportion of the grain group compared to the easy training or typical MyPlate portions. Additional grains, or carbohydrates, are recommended as activity increases to support energy needs during high intensity or long duration exercise. Although it is known that adolescents are more susceptible to being insulin resistant during puberty phases, it is still often recommended for adolescents to consume higher amounts of carbohydrates during higher activity days. This is common for those participating in practices, training sessions or competitions that are 60-120 minutes in length or have high intensity demands. Providing additional carbohydrates as a snack prior to activity is most commonly recommended to meet this elevated energy demand.

Finally, the hard training or race day performance plate will likely be used for adolescent athletes that are training at the elite level and those who are already gone through puberty. After maturation, older adolescents are able to utilized more carbohydrates for training because insulin sensitivity and glycogen storage capacity increases.

With that being said, training days that entail >120 minutes, may have multiple sessions in a day such as a pre-season camp, or competition days should be supported with grains and carbohydrates making up 50% of an athletes intake. Again, additional total energy intake will also be necessary to support energy expenditure as higher rates. For hard training days, it is recommended that athletes consume carbohydrates prior to activity, during activity, and after activity to replace glycogen stores that were used to supply activity with energy.

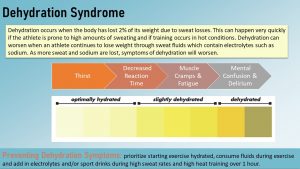

Only a Well-Hydrated Body Can Perform Optimally

For all athletes at any age, proper hydration is key to sustain exercise. Even beginning dehydration will impact performance. This is the reason why professional athletes prone to dehydration faithfully weigh themselves before and after training and competition. While research has not determined a proper hydration level for adolescents, adolescent athletes should follow the similar trends as an adult.

The baseline for hydration is to consume half of the body weight in ounces. For example a person weighing 150 pounds should drink 75 ounces of water throughout the day. This is the minimum recommended intake. With increasing physical activity, exercise, training or sport competitions the water need increases. The amount of water needed depends ultimately on the length of the training, how much you sweat (some people sweat less than others) and the climate you are training in. You already see that this is a somewhat vague recommendation.

Before: Here is what to do practically. Start the training well-hydrated and drink 16 – 20 ounces of water during the 4 hours before the training and 8 – 12 ounces of water 10 – 15 minutes before the exercise (8 oz = 1 cup).

During: Drink 3 – 6 ounces of water—a sports beverage in hot weather or for exercise over 60 minutes—every 15 – 20 minutes during the exercise. During sports or exercise it is hard to keep track of ounces of fluid. As rule of thumb 2 – 3 large gulps of fluid are approximately 3 – 6 ounces. In hot weather or during prolonged exercise sports beverages are great to replace the minerals, mostly sodium and potassium, lost in the sweat. Keep in mind that the glucose or sugar content of sports drinks varies widely. You want to choose one with not as much sugar unless you train in very hot climate.

After: Rehydrate, which means drink 16 – 24 ounces of fluid for each pound lost during exercising within 2 hours. Rehydrating allows for better recovery and rebuilding for the next training. Protein shakes have often too much protein in comparison to carbohydrate. Chocolate milk has actually the ideal combination of fast digestible sugars and high-quality protein to rehydrate and start the muscle repair process.

We gave you some rule of thumb amounts for hydration, but also cautioned that the actual amount of fluid needed for optimal hydration can vary. How do you tell?

Elite athletes weigh themselves before and after exercise to unsure that they are well hydrated. For everybody else the color of the urine is a great measurement for the hydration status. You want to see very light yellow urine. If you see anything more yellow you are not hydrating properly.

What happens if a teen athlete is not hydrating adequately. Keep in mind thirst does not always indicate inadequate hydration and the athlete will not only lose fluids sweating, but also minerals. The first symptom is a decreased reaction time which athletes are not clearly aware of. This will happen when the teen athlete lost fluids worth 2 % of the body weight. A 150 pound high school athlete would lose around 3 pounds of fluids which can easily happen in hot weather. The declining reaction time does not allow to implement learned skill sets as easily and the performance will decline. As the dehydration progresses muscle cramps and fatigue sets in. An athlete that appears confused needs to stop exercising and receive medical attention immediately.

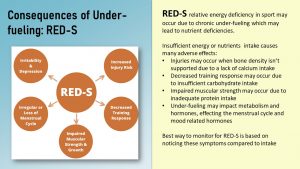

Watch Out For Symptoms of Red-S to Catch Under-Fueling

Under-fueling can easily happen in teen athletes. Often the increased energy need due to growing lean mass (BMR↑) and increased energy expenditure due to hours of training and competition is not balance by an increased food intake. Teens often skip meals and choose less than optimal foods to fuel their body. High schools often don’t provide proper dietary counseling or trainings tables and dietary counseling as colleges do. This makes the teen especially vulnerable for under-fueling.

Inadequate calcium and vitamin D intake impacts bone density negatively. Especially high-impact sports such as soccer, basketball and running can lead to stress fractures and other injuries. Insufficient carbohydrate intake from following trendy low-carbohydrate or keto diets might lead to decreased training response, low protein intake to impaired muscle strength.

If under-fueling is long-term and extreme the entire metabolism and hormonal balance can be affected. Girls might stop menstruating and the lack of estrogen will impair bone mineralization. Both genders might experience a delayed puberty which is problematic regarding keeping up with other athletes.

The best way to avoid under-fueling is to monitor symptoms of Red-S. This would include watching for inadequate response to training and irritability or even depression. It is always a red flag if a female athletes stops menstruating. The lack of menstruation is not the main problem, but the decreasing estrogen blood levels due to the under-fueling will reduce bone mineralization. This can increase the injury risk short-term and increases the long-term risk for osteoporosis. Frequent injuries should also be a reason to explore if the teen athletes has an adequate food intake.

The amount of food eaten, energy intake, depends on the weight of the athlete, sport and training intensity. A male gymnast might need 2500 kcal per day while a swimmer might need 5000 kcal. Since every athlete is so different the amount of food needed can be approximated by meeting a calculated energy intake and then watching for weight loss, weight gain and the symptoms of Red-S.

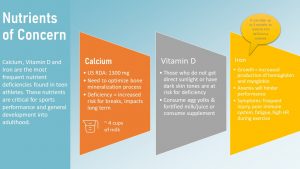

Nutrients of Concern for Adolescent Athletes

All nutrient deficiencies will have a negative impact on athletic performance and training. The following nutrients are especially a concern for adolescent athletes because they combine increased needs for growth and development, and athletic performance. These three nutrients are calcium, vitamin D and iron. Low bone mineralization due to low calcium and vitamin D intake increases the risk for injuries and stress fractures, while even moderate iron deficiency anemia impacts performance substantially.

Calcium and Vitamin D: Optimal Bone mineralization Is Important to Withstand the Stresses on Bones Due to the Sport

Calcium needs are often debated between different countries based on different research results and influence of studies. Calcium need is hard to measure because the blood calcium levels are help constant at all times. If calcium intake is low calcium is released from the bone to maintain calcium blood levels. Therefore calcium intake does not have a RDA (recommended dietary allowances), but an adequate intake. The adequate intake is set at the amount that will prevent osteoporosis later on plus additional amounts for varying bioavailability in food. It is easy to imaging that the calcium AI is hotly contested. The AI for teens is set at 1300 mg—300 mg higher than the adult AI—which would be covered by 3 cups of low-fat milk. The National Institutes of Health notes that about half of adolescents meet this recommendation.

Athletes need to optimize the bone mineralization process. Constant stress of long training and high impact on bones and joints can easily lead to fracture injuries and stress fractures if the bone is not properly mineralized. It is important to recommended sufficient calcium intake for adolescents to support bone growth. Dairy is ideal, but if the teen is lactose intolerant or doe not like milk calcium fortified soy and nut milk, fortified orange juice or supplements can replace dairy consumption.

Vitamin D deficiency may also be a concern for adolescents; this vitamin helps to absorb calcium and build bones so it is often associated with calcium intake. Vitamin D is most commonly produced in the skin by exposure to direct sunlight; just 15 minutes provides sufficient vitamin D for the day in light skinned athletes. However, it is important to note that individuals with a darker skin tone produce less Vitamin D from sun exposure compared to those with fairer skin.

Athletes who spend most time indoors for practice are at risk for vitamin D deficiency. The risk is higher in winter when UV rays from sun light are less intense and skin is covered in cold weather.

For individuals who do not get direct sunlight, or those with darker skin tones, a diet rich in vitamin D sources like egg yolks, salmon, fortified milk (keep in mind that dairy is not fortified, only vitamin D milk)or fortified juices is necessary to meet recommendations of 600 IU per day. Currently, there is a lot of misinterpreted research on vitamin D deficiency in athletes due to a misunderstanding of how to measure vitamin D. For teen athletes, it is most important to prioritize the consumption of vitamin-D rich foods and obtain sun exposure if possible.

Iron Deficiency Impacts Athletic Performance Substantially

During adolescence, the increase in growth requires additional production of red blood cells and myoglobin in the muscle. Without sufficient iron supply red blood cells and myoglobin cannot be synthesized in normal amounts. Anemia is the consequence. The requirement for iron is 11 mg for males and 15 mg for females aged 14 – 18 years old per day.

Specifically for adolescent athletes, iron is additionally important with increasing aerobic fitness and potential muscle hypertrophy. This will require additional iron for hemo- and myoglobin synthesis.

Iron deficiency can hinder performance since iron is needed for your body to transport large amounts of oxygen to the muscle cells to produce large amounts of ATP from glucose and fatty acids efficiently. The first symptom of iron deficiency anemia in adolescents is declining sports performance and increased fatigue, frequent injuries, poor immune system, and an abnormally high heart rate during exercise. Checking for iron status may be necessary and can often be checked at annual adolescent physicals. This will prevent severe iron deficiency anemia because it can take up to 3 months to fully reverse anemia. During this time the athlete will experience lower performance and by the time it is fixed the season might be over.

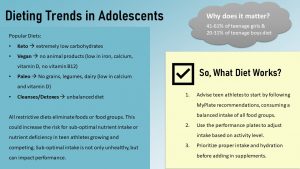

Popular Diets Promise Performance Increases Without Sufficient Scientific Evidence

Blogs and website promote the benefits of several trendy diet as performances enhancing. All trendy diets have in common that one or several food groups are completely eliminated or significantly reduced. You will find more detailed information about those popular diets in the activity resources section. Low-carb diets reduce carbohydrate under the recommended amount while the keto diet almost eliminates carbohydrates. Both diets are promoted as a strategy to increase the efficient utilization of fat as an energy source and therefore reducing the reliance on limited glycogen stores. This seems to be a benefit for extreme endurance athletes, but most other athletes will more likely see decline in performance due to the lack of glucose. Keep in mind that fat is a slow energy source and not appropriate for high intensity, explosive, fast sports.

Vegetarian diets eliminate animal products, either meat, fish and poultry or all animal foods in vegan diets. Both vegetarian diets can support athletic performance, but the athlete must be well educated how to choose foods and how to combine foods effectively. Otherwise, the high energy density of vegetarian diets will make it difficult to consume enough energy, lower protein quality can lead to insufficient amino acid supply if foods are not properly combined, and iron deficiency. Vegan diets or vegetarian diets low in dairy and eggs can easily lead to insufficient calcium and vitamin D intake.

Teens are exposed to similar diet trends that promise performance increases and often use elite athletes as examples for the efficiency. However, for the growing teen this risk for insufficient energy and nutrient intake is increased due to the combination of growth, development and increased energy needs due to the intensive training. Research shows that many teens have dieted at least once. This is linked with common body dissatisfaction or desire to change the way they look as they are going through puberty.

For the any athlete, let alone a teen athlete on a popular diet it is hard to say how much of the performance is due to the diet. It also cannot be excluded that the performance would improve if the teen athlete would start a healthy mixed dietary pattern like the performance plates. Individual teen athlete will have a very subjective estimation of their performance. Therefore studies would be important to see how popular studies impact performance in a blinded study setting. These studies are lacking though and the claims of performance enhancement are almost entirely based on subjective opinions of individual athletes or trainers.

It is important to educate teens, especially teen athletes, that the best “diet” to follow to promote athletic progress is by following MyPlate and consuming a balanced diet, emphasizing fruits and vegetables, whole grains, lean protein and limiting added sugar and ultra processed foods.

Can Adolescent Athletes Improve Performance By Taking Supplement?

First things first: Before a teen athlete even starts thinking about supplements healthy eating as suggested by the athlete performance plates should be implemented. That leaves the question that many teen athletes and their coaches have: Can I increase performance by taking performance enhancing supplements?

The answer: we know very little about the effects of supplements on adolescents. The problem is two fold here; it is hard to tell what stage of puberty adolescents are in who consume supplements and experience effects, and long term effects have not been researched. Supplements are typically promoted online or by a coach who does not have a nutrition education background. The challenge here is that teens blindly take supplements that are unregulated by the FDA and not researched enough to support proven results. Popular supplements taken by teens are reviewed next:

Protein Powders: Protein powder should almost be in a separate category, however it still qualifies as a supplement when consumed in an extracted form such as a powder. Protein powders are typically in a whey protein form, which is a fast acting protein supplement. This is taken as a post-workout supplement with the idea that it aids in muscle repair and muscle protein synthesis. While this is a proven supplement for adults, teens may not have the same outcomes. This is because teens repair muscles at different rates if they have not fully gone through puberty. Protein powders may still aid in muscle gains, but it is not guaranteed since they digest and utilize protein at different rates.

Creatine: Creatine is another popular supplement geared to promote muscle gains. Safety of this supplement has not been studied in adolescents, but there is typically low adverse side effects. From acute studies, adolescents will likely not obtain the same results as adults. These studies show that there were no significant effects on anaerobic performance when creatine was taken by adolescents. Although coaches and media may promote creatine as a simple way to improve performance, studies do not support this supplement during the adolescent athlete who has not undergone puberty.

Advice for Adolescents Taking Supplements: If adolescents insist on taking a supplements, which there are thousands of kinds to choose from, the best advice you can give is to consult a Registered Dietitian and Primary Care Physician to assess if that supplement may have significant risk. When choosing a supplement, choose a NSF Certified product which ensures that the ingredients listed are all that’s included in the supplements, providing a safe quality supplement.

Interested?

Sport during puberty growth: Recommendations by the American Acdemy of Pediatrics

https://www.teamusa.org/nutrition

References

Cheng HL, Amatoury M, Steinbeck K. Energy expenditure and intake during puberty in healthy nonobese adolescents: a systematic review. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;104(4):1061-1074. doi:10.3945/ajcn.115.129205

https://www.nal.usda.gov/sites/default/files/fnic_uploads/energy_full_report.pdf

Clénin, G., Cordes, M., Huber, A., Schumacher, Y. O., Noack, P., Scales, J., & Kriemler, S. (2015). Iron deficiency in sports – definition, influence on performance and therapy. Swiss Medical Weekly, 12. https://doi.org/10.4414/smw.2015.14196

Desbrow, B., McCormack, J., Burke, L. M., Cox, G. R., Fallon, K., Hislop, M., … Leveritt, M. (2014). Sports Dietitians Australia Position Statement: Sports Nutrition for the Adolescent Athlete. International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism, 24(5), 570–584. https://doi.org/10.1123/ijsnem.2014-0031

Jagim, A. R., Stecker, R. A., Harty, P. S., Erickson, J. L., & Kerksick, C. M. (2018). Safety of Creatine Supplementation in Active Adolescents and Youth: A Brief Review. Frontiers in Nutrition, 5, 0–8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnut.2018.00115

National Institutes of Health. (2020, March 26). Calcium fact sheet for health professionals. Retrieved from https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Calcium-HealthProfessional/

Petrie, H. J., Stover, E. A., & Horswill, C. A. (2004). Nutritional concerns for the child and adolescent competitor. Nutrition, 20(7–8), 620–631. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2004.04.002

Salam RA, Das JK, Ahmed W, Irfan O, Sheikh SS, Bhutta ZA. Effects of Preventive Nutrition Interventions among Adolescents on Health and Nutritional Status in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients. 2019 Dec 23;12(1):49. doi: 10.3390/nu12010049. PMID: 31878019; PMCID: PMC7019616.

- Glycogen is the storage form of carbohydrates and can be used to provide energy during long duration or high intensity activity. ↵

Feedback/Errata