25 The Social Influences of Peers and Parents on Body Image and Eating Behaviors

Eric Buhs and Eric Hanzel

How satisfied are you with the image that you see when you imagine your body and appearance?

How do you think other people view your body?

Have your family or friends said things to you that changed how you view your body or changed the way you eat?

For many of us, once we start thinking about questions like these, the questions and concerns can go on a lot longer than is probably good for us. Spend too much time thinking about these things and you may end up wanting to lock yourself away and never come out. We have a word for that kind of repetitive thinking or worrying – rumination. It’s usually best to avoid that when you can. This kind of rumination and other effects from body dissatisfaction and negative body image have been linked to the development of depression, eating disorders and other important health issues. This chapter may help you understand some of the major influences on your body image and may help you understand how social relationships impact the development of body image.

You Will Learn:

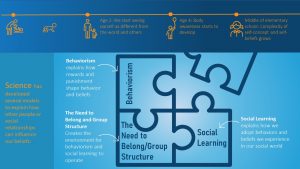

- The development of self-concept and self-believe starts during elementary school

- Scientists discuss several psychological models of social influence and body image outcomes

- Behaviorism explains how rewards and punishment shape behavior and beliefs

- Social learning explains how we adopt behaviors and beliefs we see and experience in our social world

- Our need to belong and group structure creates the environment for behaviorism and social learning to operate

- Peers, parents and eating behaviors

- Summary: A new(er) role for positive body image

- The rocky road to a positive body image

The Development of Self-Concept and Self-Believe Starts During Elementary School

So why are we so concerned about our bodies and, especially, the way we appear to others? As usual, the answer is complicated and depends on both the social environment you were raised in and the genetics you were born with. Changing your genetics is a scientific and moral minefield and those issues go way beyond the scope of this chapter, so we’ll focus on factors in the social environment that play important roles in how we develop our body image and develop attitudes towards our physical appearance.

To start with, we need to go deep into our personal histories. We start developing a self-concept and specific beliefs around our bodies and our appearance when we are toddlers. Usually around the age of two, our minds develop a more complex ability to see ourselves as separate from others in the world and as individuals with distinct thoughts that are different from others in our social world. By age four we have the cognitive ability to compare ourselves to others and by age 5 we start to develop awareness of our own body.

These beliefs and attitudes continue to develop over our lifetimes, but some critically important things start to happen in later childhood, usually around the middle grades of elementary school. At this point we start to develop distinct areas or domains of self-concept which describes the different ways we view ourselves. As small children, we tended to see ourselves in broad, general ways, that is to say that we thought, “I am a good (or bad) person,” (a global judgement of self-esteem) but in middle childhood we start to see ourselves in a more complex way. We think about ourselves distinctly in separate areas such as academic competence, social acceptance/competence, athletic competence, and physical appearance. We develop the ability to feel that we may have high abilities in one area and low abilities in others, for example. You may feel that you are highly skilled socially, but are below average athletically, etc. Body image starts to be a distinct part of our self-concept that may or may not be as positive, or perhaps as negative, as our beliefs about other areas of our self-concept. As an example of the importance of how we feel about our bodies and appearance, physical appearance is often the single most important predictor of self-esteem and overall self-concept for adolescents. By the mid-elementary school, for example, as many as 40-50% of girls and 25% of boys may be dissatisfied with their weight

As we develop these critical beliefs about our bodies (or other parts of the self), psychologists have shown that the social world that we live in and our social relationships play a key role in how these self-beliefs and self-concepts develop. Here we will focus on the two main types of relationships that we know play important roles in shaping body image and related attitudes and behaviors – peers and parents. While peers and parents may provide positive support for body image, unfortunately most of the effects research has uncovered so far tend to be more strongly negative and most of the findings we discuss below are not in a positive direction. First, however, we need to learn about the different ways that other people or social relationships can influence our beliefs.

Behavior Patterns, Social Learning and Our Need to Belong Influence the Development of Believes About Our Body

The Psychology of Influencing Behavior Directly: Behaviorism Explains How Rewards and Punishment Shape Behavior and Beliefs

You’ve probably heard of behaviorism or you are at least likely to be familiar with how it works on a practical level. Behaviorism operates on the idea that rewards (also called reinforcements) increase the frequency of a behavior and punishment (also called negative reinforcements) decreases the frequency of a behavior. If you have trained a dog to obey commands using treats, you get the general idea. When the dog obeys a command they get a treat and we hope the behavior frequency increases. When they do not obey, the treat is withheld or a negative reinforcement is given (“Bad dog!”) and that behavior should decrease. Humans work much the same way, even though we typically develop very complex sets of behaviors and attitudes.

When we are kids, our parents reward certain behaviors – like cleaning your plate at meals or exercising by giving us tangible rewards (like ice cream) or positive verbal praise. Over time these reinforcements and the behaviors that they promote or punish become part of our daily behaviors even when parents may not be around. That is to say, we internalize some of the reinforcements and start to reward/punish ourselves to maintain the behaviors or beliefs. In this way, the behaviorist environment that our parents create can become part of our “selves” and strongly influence the way we act and think. As we become toddlers and develop peer relationships, peers can influence our behaviors the same way. As we get older and especially as we become adolescents, peer relationships can exert even more behaviorist influences on us than our parents and families. In this way, the behavior and attitudes of the people around us can have very important effects on the way that we see ourselves and our bodies. Many times these complicated sets of beliefs that we have about our selves are positive, but we are usually most concerned when they become negative.

What are some negative patterns that can show up?

There are some specific pathways or processes via which body image and body dissatisfaction appear to be impacted by these types of interactions with others. Mothers, in particular, have been shown to play a key role as social reinforcers for adolescent girls’ eating attitudes and behaviors. Encouragement to lose weight from mothers was also correlated with young girls’ desire to be thinner. Other studies showed that kids whose parents let them know that they are concerned about their weight were also more likely to have negative body image (Ricciardelli & McCabe, 2001).

Teasing by peers is another social behavior that can act as a negative reinforcement that shapes our body image. Suggestions or encouragement for dieting from same-sex peers can also apply reinforcing pressure for that behavior or, conversely, reinforce a negative body image (Ricciardelli & McCabe, 2001).

Finally, as many people often guess, it’s important to note that these effects seem more common and stronger for girls. Boys can also be affected by these types of social interactions, of course, but girls and women tend to show higher rates of problems. Teasing by peers, for example, seems to affect both genders, but some studies have shown that parents’ comments to boys weren’t related to a desire to be thinner, etc. while they those comments did predict that desire for girls. On balance, there is more evidence that girls are more strongly affected by these types of direct comments, or reinforcements, regarding body image. This could also be true not because parents’ comments don’t affect boys, but because they tend to say these kind of things to boys less often than they do to girls.

The Psychology of Modeling Behaviors: Social Learning Explains How We Adopt Behaviors and Beliefs We See and Experience In Our Social World

You may, however, already be thinking about some problems with the behaviorist approach if we try to use it to explain all effects on body image and body dissatisfaction. One issue is that, as young children, we grow up to become highly complex people very, very quickly. It would be hard for anyone, whether it’s peers or teachers or family, to follow us around as we grow up and provide reward/punishment for ALL of the beliefs and behaviors that we develop. To help explain other ways the social world affects us, Albert Bandura developed a model of other social pathways that influence our behaviors – he called his model social learning. His basic idea was simple: we sometimes copy and learn behaviors or beliefs that we see/hear around us without anyone directly rewarding us. We also often avoid a lot of other behaviors without someone punishing us. Through a long series of experiments, Bandura showed that observation is all that’s required for us to pick up new behaviors or attitudes. He called this observational learning. We see and learn others’ actions and later, sometimes, we copy them and act them out without anyone telling us to do so or giving us rewards (or punishment) when we do.

It can’t be quite that simple though, right? We don’t copy everything we see or hear. Why do we copy some people and not others?

If we think that the people we observe are highly similar to ourselves we are more likely to copy them. Models who we perceive as similar in age, gender or ethnicity, for example, are more powerful influences on our behavior than people we perceive as not like us.

If we see them as socially powerful or with high status, we are also more likely to copy them (think media stars or pro athletes), and vice versa.

We also take into account how we see the people we observe get treated for certain behaviors. If we see a character on a TV show get rewarded for being violent, for example, we may be more likely to copy that behavior. That example also makes it clear that a social learning model creates a potentially powerful role for media in influencing our beliefs and behaviors. It was no coincidence that Bandura developed his theory as TV was becoming common in U.S. households in the late 1950s and 1960s.

Our personal relationships still appear to be more common and powerful sources of social learning, though – peers and family are usually more likely to influence our behavior than media personalities, although these personal and media influences can combine to even more powerful when they are modeling similar behaviors. Behaviorism still has a role to play in social learning as well – rewards or punishments that follow behavior we copy from others will still affect our tendency to behave that way (or not).

How to Model Healthy Attitudes For Young People

- Set a Positive example of a healthy and balanced relationship with food: Don’t talk about or behave as if you are constantly dieting; encourage eating a broad variety of foods in response to body hunger. Don’t equate food with positive or negative behavior. The dieting parent who says she was “good” today because she didn’t “eat much” teaches that eating is bad, and that avoiding food is good. Similarly, “don’t eat that—it will make you fat” teaches that being fat makes one unlikable. Learn about and discuss with your sons and daughters the dangers of trying to alter their body shape through dieting. Trust your children’s appetites; never try to limit their caloric intake—unless requested to do so by a physician for a medical problem.

- Help children accept and enjoy their bodies and encourage physical activity: Love, accept, acknowledge, appreciate, and value your children—out loud—no matter what they weigh. Convey to children that weight and appearance are not the most critical aspects of their identity and self-worth. Do not communicate the message that you cannot dance, swim, wear shorts, or enjoy a summer picnic because you do not look a certain way or weigh a certain amount. Notice often and in a complimentary way how varied people are—how they come in all colors, shapes, and sizes. Show appreciation for diversity and a respect for nature. Link respect for diversity in weight and shape with respect for diversity in race, gender, ethnicity, intelligence, etc. Educate your children about the existence, the experience, and the ugliness of prejudice and oppression—whether it is directed against people of color or people who are overweight.

- Encourage critical thinking: The only sure antidote to the tendency to conform to the powerful seduction of the media and peer pressure is the ability to think critically. Become a critical consumer of the media—pay attention to and openly challenge media messages. Talk with your children about the pressures they see, hear, and feel to diet and to “look good.” Parents have to encourage critical thinking early, and educators have to continue the mission. We need to teach kids how to think, not what to think, and to encourage them to disagree, challenge, brainstorm alternatives, etc.

What negative patterns did research find?

Parents, as we covered above, seem to play a big role in modeling body dissatisfaction in a way that impacts their kids and impacts girls especially. Mothers who complained about their own weight and mothers and fathers who attempted weight loss themselves had daughters with poorer body-esteem (Smolak, Levine, & Schermer, 1999).

Peers and peer groups also appear to function as important models. A group of 13-18-yr-olds, for example, reported strongly negative effects on their body image from pressure to conform to peer group expectations about appearance. They also reported negative peer experiences if they failed to conform (e.g., teasing; Kenny, et al., 2017) – this may show how behaviorist and social learning models combine – peers served as models of appearance and provided negative reinforcement if their friends didn’t conform to expectations.

You are also probably already thinking (as Albert Bandura did originally) that media is also likely a big source of influence and social learning about body image, eating behaviors, etc. These studies are difficult to do scientifically because it is hard to separate out all the different possible types of media effects and compare them to possible effects from peers and families, etc.

The studies that have been done, however, do tend to show that media images, social media, and messages in music, etc., may have some effects on body image and eating disorders. The effects that they find tend to be fairly small, however, when compared to the effects peers and families have.

Even though commercial and social media platforms present thousands of images of idealized bodies on a daily basis, the effects from the people we have direct social relationships with is likely a lot stronger than potential media effects. A study from Ferguson and colleagues, for example, showed that television exposure and social media use did not affect body image (thin ideals) and disordered eating on their own when peer effects were also included in the analyses. The peer effects (feeling inferior to other girls) were much stronger than the media influences in their study (Ferguson, et al., 2014) and other studies have found similar patterns.

The Psychology of Group Effects: Our Need to Belong and Group Structure Creates the Environment For Behaviorism and Social Learning to Operate

Given how common both social models and behaviorist reinforcements are in our daily lives, it’s not too hard to see how both behaviorism and social learning might influence both our body image and our eating behaviors. Parents and peers often have a very direct and powerful role both as reinforcers (negative and positive reinforcement) and as social models. They influence how and what we eat, how active we are, and what types of bodies and appearances are rewarded or valued in our social groups. There is also another aspect of social relationships that it is important to talk about here – the role of our need to belong to social groups and the social structures of those groups.

The first part of this is relatively easy to understand. Humans have a powerful motivation to belong to social groups and to have and maintain relationships. Some psychologists call this the “fundamental human need to belong” (Baumeister & Leary, 1995). Some of us need a lot of relationships to feel belonging, others need fewer, but we all need at least a few and our very strong motivation to maintain these relationships means that we will usually try hard to keep some people around and this creates an environment where both behaviorism and social learning may strongly influence how we act and think.

Our participation in these groups has another method that usually influences our thoughts and behaviors – the structure of the group. Whether it is our family, the kids in our neighborhood, or the peer groups we are part of at our schools, they all develop attributes that impact how the people in that group act. First, every group has rules about how the people in that group need to act and think/speak to be part of that group. To be considered a jock, there are ways of dressing and speaking that are required (more or less) to be considered part of that group. Your motivation to be part of the group helps influence whether you are willing to conform to those standards. The same holds for church groups, political groups, and workplace groups alike. Second, your status or power in the hierarchy of the group also affects how you think and act – if you are high status and a group leader, you can set trends or rules about how to dress, what kind of body type if preferred (think “mean girls” or a soccer team). If you are lower status and trying to get into a group, you may be more likely to copy the dress and attitudes of the group leaders as you try to gain favor from them. Finally, there may be other ways for groups to affect body image and body dissatisfaction – groups you are not a part of or have no interest in being part of may push you to actively reject or oppose those standards and, depending on your attitudes about the people in the group, affect your attitudes and behaviors that way.

What negative patterns did the research find?

Specific studies that directly examine peer group belonging effects haven’t been done yet, but the important point here is that the direct effects from behaviorist reinforcements and social learning models that we covered above are usually occurring within the context of social groups.

Behaviorist effects can be more powerful in groups because being part of a group will typically increase the opportunity and frequency for people in those groups to reinforce certain behaviors for you.

Being part of a group will also increase our exposure to group members as social models. The more we see the appearance standards presented by members of a group that we want to be a part of (and those who we would like to be similar to), the more likely we may be to copy them.

This is the same pattern we discussed above when we covered social learning effects. If we look at these effects through this lens, then our motivation be part of a group is an important factor that likely contributes to both behaviorist and social learning effects on body image and body dissatisfaction.

A good example of how this may work is a study by Shroff and Thompson (2006) that showed that adolescent girls reported effects from their groups of friends on their own body dissatisfaction, eating problems and self-esteem. Another study by Jones and colleagues (2004) showed that both girls conversations with friend groups about appearance and body image and groups’ direct criticisms of their appearance and bodies contributed to greater body image dissatisfaction.

We should also note that some studies have also found positive effects for social support from friends in protecting or providing a buffer against body dissatisfaction – so the effects can go both ways.

Peers, Parents and Eating Behaviors

One important way that relationships with peers and parents may impact mental health and health in general is through the potential links to eating behaviors. Eating disorders are discussed elsewhere in this text in more detail, but the kinds of social effects that we discussed above on body image and body dissatisfaction are also likely to impact child and adolescent eating behaviors. Understanding the potential effects of pressure from parents and peers is an important part of efforts to decrease disordered eating.

Disordered eating is much more common among female kids and adolescents. For this reason many of the studies conducted so far have focused on girls, but effects for boys have been examined as well.

One study looked at both adolescent girls and boys and showed that family pressure to lose weight was reported by both boys and girls (Ata et al., 2007). The effects appeared to differ by gender though. Girls reported more pressure to lose weight and more teasing, and this was linked to more negative body attitudes and, especially, high risk eating attitudes and behaviors.

Boys reported lower parent support and more pressure for building muscle that was linked to higher risk eating behaviors and attitudes. As this evidence implies, these types of parental effects appear to be strongest when parents are directly telling their kids to lose weight or participating in dieting themselves (Benedikt, et al., 1998).

There is another group of studies that has found support for links between teasing and bullying by peers and later disordered eating. Sweetingham and Waller (2008), in a follow-back study, found that adolescent girls with eating disorders reported teasing and bullying that predicted higher levels of shame and that this predicted the severity of the diagnosed disorders.

Lee and Vaillancourt (2018) also found that disordered eating (and depression symptoms) was consistently associated with bullying for adolescent boys and girls across a five-year period.

Other studies (e.g., Keel et al., 2007) have shown that exposure to friends who were dieting predicted later body dissatisfaction and extreme weight control behaviors such as fasting and induced vomiting.

Finally, an overarching analyses of findings from dozens of studies showed a consistent, significant overall effect for both peer and family influences on disordered eating. This analysis looked at many different types of studies and the researchers saw that most of them showed that these closest relationships do tend to have important effects on eating behaviors. Social modeling and behaviorist influences are two of the key processes that are often implicated in understanding the psychological pathways that these influences follow as they impact our beliefs, behaviors and later adjustment.

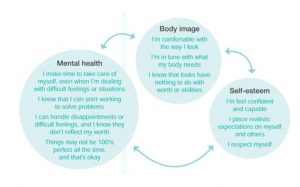

Summary: A New(er) Role for Positive Body Image

The evidence suggesting that body image and body dissatisfaction play a critical role in our mental and physical health is, at this point, pretty powerful and comes from hundreds of studies over decades of research (e.g., Markey, 2010). The prevalence of body dissatisfaction in adolescents has been estimated at rates as high as 40% for boys and 80% (!!!) in girls (Kostanski & Gullone, 1998) and has been consistently linked to anxiety and depression (including suicidality) in many of these studies.

We also know that our families and peers are major contributors to body image as well—unfortunately much of that influence appears to be negative. There is positive news, however, and more recent research and intervention efforts have targeted positive body image as a way to combat the pervasive negative effects in our relationships and society.

Developing a positive body image is emerging as a powerful way for us to combat the negative and sometimes severe effects of body dissatisfaction and relationship pressure to conform to unrealistic standards of appearance and body type (see Daniels, et al., 2018 for an edited book covering this topic). This newer evidence and attempts by health professionals to change the type of influence that our social relationships might have on our body image has begun to show us a path where these influences can become powerful contributors to positive adjustment and better mental and physical health.

Steps to a Positive Body Image

We covered some important models that tell us exactly how our social relationships might influence body image and eating behaviors. Some of the evidence supported the idea that these models can be used for positive influences – not just promoting negative patterns and problems. Many organizations and mental health counselors and therapists (see links below) specialize in providing support as we try to create more positive body images for ourselves and to maintain the healthy eating behaviors that go with it.

How can I encourage a healthier body image?

- Treat your body with respect.

- Eat well-balanced meals and exercise because it makes you feel good and strong, not as a way to control your body.

- Notice when you judge yourself or others based on weight, shape, or size. Ask yourself if there are any other qualities you could look for when those thoughts come up.

- Dress in a way that makes you feel good about yourself, in clothes that fit you now.

- Find a short message that helps you feel good about yourself and write it on mirrors around your home to remind you to replace negative thoughts with positive thoughts.

- Surround yourself with positive friends and family who recognize your uniqueness and like you just as you are.

- Be aware of how you talk about your body with family and friends. Do you often seek reassurance or validation from others to feel good about yourself? Do you often focus only on physical appearances?

- Remember that everyone has challenges with their body image at times. When you talk with friends, you might discover that someone else wishes they had a feature you think is undesirable.

- Write a list of the positive benefits of the body part or feature you don’t like or struggle to accept.

- The next time you notice yourself having negative thoughts about your body and appearance, take a minute to think about what’s going on in your life. Are you feeling stressed out, anxious, or low? Are you facing challenges in other parts of your life? When negative thoughts come up, think about what you’d tell a friend if they were in a similar situation and then take your own advice.

- Be mindful of messages you hear and see in the media and how those messages inform the way people feel about the way they look. Recognize and challenge those stereotypes! You can learn more about media literacy at www.mediasmarts.ca.

- Ask your community center, mental health organization or school about resiliency skills programs, which can help people increase self-esteem and well-being in general.

Accessed at: Canadian Mental Health Association

Interested? More resources:

10 Steps to Positive Body Image

Mayo Clinic – Healthy body image: Tips for guiding teens

Body image: Preteens and Teenagers

Body Image in Childhood

Body Image, Self-Esteem and Mental Health

References

Baumeister, R. F. & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 497-529.

Daniels, E. A., Gillen, M. M., & Markey, C. H. (Eds.). (2018). Body positive: Understanding and improving body image in science and practice.

Jones, D. C., Vigfusdottir, T. H., & Lee, Y. (2004). Body image and the appearance culture among adolescent girls and boys: An examination of friend conversations, peer criticism, appearance magazines, and the internalization of appearance ideals. Journal of adolescent research, 19(3), 323-339.

Keel, P. K., Baxter, M. G., Heatherton, T. F., & Joiner Jr, T. E. (2007). A 20-year longitudinal study of body weight, dieting, and eating disorder symptoms. Journal of abnormal psychology, 116(2), 422.

Kenny, U., O’Malley-Keighran, M. P., Molcho, M., & Kelly, C. (2017). Peer influences on adolescent body image: friends or foes?. Journal of Adolescent Research, 32(6), 768-799.

Kostanski, M, Gullone, E (1998) Adolescent body image dissatisfaction: Relationships with self-esteem, anxiety, and depression controlling for body mass. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 39(2): 255–262.

Lee, K. S., & Vaillancourt, T. (2018). Longitudinal associations among bullying by peers, disordered eating behavior, and symptoms of depression during adolescence. JAMA psychiatry, 75(6), 605-612.

Marcos, Y. Q., Sebastián, M. Q., Aubalat, L. P., Ausina, J. B., & Treasure, J. (2013). Peer and family influence in eating disorders: A meta-analysis. European Psychiatry, 28(4), 199-206.

Sweetingham, R., & Waller, G. (2008). Childhood experiences of being bullied and teased in the eating disorders. European Eating Disorders Review: The Professional Journal of the Eating Disorders Association, 16(5), 401-407.

Markey, C. N. (2010). Invited commentary: Why body image is important to adolescent development. Body Image, 1, 15-28.

Tylka, T. L. (2018). Overview of the field of positive body image. Body positive: Understanding and improving body image in science and practice, 6-33.

If you imagine eating behavior as a spectrum, disordered eating sits between normal eating and eating disorder. Disordered eating may include less frequent and severe symptoms and behaviors of eating disorders. How disordered eating expresses itself varies. Potential behaviors include restrictive eating, compulsive eating, or irregular or rigid eating patterns.

Feedback/Errata